Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 12/04/2024 in all areas

-

There is of course the real concern that bodies like the NBTHK are "not up to the job." However, I think we also have to take responsibility for over relying on shinsa to do the thinking for us, especially in the case of mumei tosogu. Because the current system of certification doesn't seem to provide anything beyond some basic descriptions of motifs and features of the tsuba before making a final pronouncement of attribution ("den" at best if there is some uncertainty) to a single school or style, the judges are hard pressed in many cases when the tsuba display features of many schools, categories, and styles. There is a made-up category that I have been using called "generic Edo" because of the mish-mash of styles and influences that are observed in tsuba produced after Early Edo when tsubako are being influenced through interaction in capital cities, along major trade routes, and through apprenticeships. Submitting such pieces to shinsa will predictably result in invocation of the black box and the frequent attribution of "Shoami," right? How does that help? And why does that leave many feeling uncomfortable or dissatisfied? In other words, the problem is not as simple as pointing a finger at NBTHK or any other expert body or organization. It's the very issue that Glen is trying to address with this series of threads. WE have to study, study, study. WE have to question, question, question. WE have to challenge, challenge, challenge. WE have to network with each other to play an active role in scholarship within our own community, because our motives--born out of a pure love of beautiful art--are not subject to the potential biases that may be introduced by sellers, academicians, and other experts. Sorry, it seems that this belongs more in the thread on #3 related to schools and shinsa, where the topic discussion is progressing nicely. Oh well.5 points

-

Thomas, in some way You are right, it’s the same old story of supply and demand. There was a time, I also thought gaining a papered piece is the top of bliss. But someday I had the opportunity to buy something and asked if it is papered. The seller asked me in return, if I do collect papers? At this point I became grounded and I possess many pieces today without paper. Nice to have them, but it is more important to recognize the quality of a piece itself. Alas, many folks are still blended by papers or even worse demand them to be sure. BTW: The limitations at the shinsa is a result of missing judges, too. I think if they had enough board members, they could manage the flood of submissions as well… Florian4 points

-

Please see attached Steve Waszak's paper on the Yamakichibei atelier that is uploaded on NMB. It addresses precisely some of the points raised by Thomas, but Steve uses stylistic relationships in addition to well established features of mei to suggest an alternative theory on the chronologic relationship of the 5 masters of the Yamakichibei workshop. So, it isn't necessarily true that there isn't evidence "to determine which artist was the founder or primary artist and what order they worked in." Rather, it is important to use the inductive approach that begins with the features of the tsuba in hand, rather than "received wisdom" from older scholarship that is not based in factual evidence. The Yamakichibei Group of Tsubako.pdf4 points

-

So it's probably just a scratch then. If you're genuinely concerned, you could see if you can return it? I suspect that you're going through what most of us went through with our first blade where there is a tendancy to worry that what you have is flawed in some way and perhaps significantly. The green papers are not necessarily a problem of themselves, but if they give the name to a big name smith then you might get a different result if you submitted the blade to shinsa today. The trick is not to have paid big name money for a minor smith, but I'm sure you've done fine.3 points

-

Hi Dee, If it's only on one side, I'd tentatively suggest that it's just a scratch and nothing to worry about. Does it cross the back (mune side) of the kissaki? If you post some pictures of that and the other side you'll get some better opinions. Out of interest, does the blade have papers?3 points

-

I have read it, I think it does a good job of outlining some of the issues that prompted this thread, there are similar issues with Nobuie etc.3 points

-

3 points

-

You will love it. It is freaking HUGE!3 points

-

Just playing devil's advocate here - Of the results arising from NBTHK shinsa what percentage could be regarded as wrong ? Same question but in the views of Western collectors and dealers ? Are these ( wrong attributions ) grievous enough to change the entire current system ? How strong would the arguments need to be to overthrow the time and investment by numerous academics and dealers who have a vested interest in retaining the status quo ? Perhaps an alternative society to give opinions with a more 'western and modernist' slant could be set up ? Take the responsibility away from the NBTHK to look at Tosogu as they are clearly not up to the job ? Is part of the problem that genuine expertise in this field is disappearing at an alarming rate, thereby giving less able 'experts' more of a say than in older days? Is there a danger of the opinion/attribution being more highly regarded than the piece itself ? Even more so than today? Interesting thread though, great to see opinions on this. Regards3 points

-

I started off writing about the "schools issue" but then it was really hard to separate it from the "NBTHK papers" issue since they are the major perpetuators of these school constructs... So here's a little starter to think about: The MAJORITY of the supposed "schools" of sukashi tsuba makers have NO period documentation to prove their exact timing or duration of production, nor their area of production. Kanayama, Owari, Heianjo-sukashi/kyo-sukashi, and especially the "ko-shoami" (one of the most laughable attempts to "create a school" I have seen yet). These were all 20th century CONSTRUCTS that were created on suppositions and inferences starting with Akiyama, and were perpetuated and "refined" by many of the tsuba collectors and authors he influenced, like one of his later students Torigoye. Sasano also adhered to these categorizations and published his works in English, which then set the “doctrine” in stone for most of the English speaking collectors around the world. Most people would assume that Japan’s NBTHK is the foremost authority on the identification and classification of tsuba, and often defer to their perceived authority as though they have access to secret tomes and manuscripts that they must be referring to in order to make their judgements. Unfortunately this is not the case and they clearly don’t even take the time to look into their own past attributions because they frequently contradict themselves or offer up different assessments for the same tsuba that has been submitted on more than one occasion. They probably take more time to write the paper itself than they do to assess the tsuba in front of them. It’s just a “cash cow” for them… easy money. Unfortunately the NBTHK is predominantly (maybe even exclusively?) populated by people who have adopted these Akiyama-type school names and labels. Keep in mind they are a private organization, who get paid to "certify" that a sword or sword fitting was genuinely produced by a specific maker, or by one of the "schools". So, it is safe to assume that they will inherently act in their own self interest to perpetuate the system they have created. As a result, they have either knowingly or unknowingly magnified the problem of attributions for unsigned tsuba, because there are a limited number of groups to choose from in the Akiyama framework, so they have frequently “expanded” the original grouping to include a variety of “outlier tsuba” with significantly different characteristics, but somehow similar enough that they thought they could all be "acceptably" grouped together under the same banner. Somewhere along the way, people within this organization decided that was the right way to go… which makes sense, because I could see that if they didn’t do that, people would stop paying money to an organization that frequently gave back papers saying “unknown maker or school of production, but here’s a pretty paper that says so…” Unfortunately, there is no visible attempt by this group to do any further study based on detailed comparison. And thanks to the internet, the accumulation of contradictory examples of their attributions is continually building and revealing the serious flaws and contradictions within this paid, for-profit system. Under a better system, these groupings should be split up into separate groups of makers (based on the shared common characteristics in the manner of the tsuba’s production), and each group given its own name or title rather than being lumped together under the same artificial banner for the sake of simplicity and maintaining the established system. Something like Haynes’ systematic numbering of known tsuba smiths who signed their work. For example, I bet we could start parsing out all the examples of “Kanayama” and “den Kanayama” by looking at details such as the tegane (punch marks) around the nakago-ana, the seppa-dai dimensions and proportions, the manner in which the corners and edges of the sukashi are done, the position of “iron bones” along the face of the mimi (rim of the- tsuba) etc… I'm certain we could even start grouping them by individual smiths within the larger group. Ideally, a non-invasive technique should be used to identify the percentage composition of the elements found in the steel, so we can more easily group tsuba together by location of their source of sand iron that was used to make the steel (even if we probably couldn’t know where that specific sand iron came from within Japan…).2 points

-

If it's only visible on one side of the kissaki, then it might just be a scratch. Hard to say based on this photo alone, but my gut leans toward superficial scratch - possibly from drawing from, or inserting into the saya. Looking forward to more photos when you get the sword in-hand. Cheers, -Sam2 points

-

2 points

-

Florian, but aren't we ourselves to blame? It used to be time-consuming and expensive to submit a tsuba for a hozon, for example. There was also no internet in the past, and in the early years there were only very few dealers with the corresponding goods and papers. But we want papers! We expect every dealer, whether in Japan or elsewhere, to offer his tsuba with papers if possible. And the dealers react and are happy to provide everything with Hozon because it sells much better. The market only reacts to us, the collectors! And now we are complaining about hozon inflation. We are responsible for this, not the NBTHK! The NBTHK has reacted! The mass of submissions was far too great. Now it is limited. It has become more difficult, or at least more time-consuming, to submit ornamental rates or blades.2 points

-

Besides the attribution: In my younger collector days (decades ago) a Hozon-paper was something special and proofed a certain grade. But today Tsuba from top to low End got Hozon so it became an inflationary practice and says nothing about quality at least. IMHO these papers will loose more and more significance (as the former Kicho-Papers have). If there will be maybe a revision of the certification system it can only be build up on levels of quality to become reliable again. Florian2 points

-

2 points

-

Common design/execution, appearing in numbers in Korea and Manchuria, associated with 16th century battlefields. They are more or less all alike, as shown in attachment. In local finds, they outnumber tosho/katchushi plates about three to one. This taking into account most plates are probably continental in origin.2 points

-

I am trying to understand which "sukashi" tsuba are being considered: Complex asymmetric designs? Or the ones which have at least central, possibly greater symmetry (rays, wheel, whatevver the name one wants to assign)? They appear in Kofun?? So is the statement they disappeared and then reappeared?2 points

-

And when is Sotheby's ever right? In this case, Jean, the auction house is likely spouting outdated tsuba scholarship. I have seen numerous sellers offering the same tag line: "Get your very very very early Muromachi period Kanayama tsuba, right here. It's the real deal."2 points

-

Along these lines, it's important that we take an inductive approach by looking at the evidence. All art scholarship starts with the description of the objects at hand along with the socio-politico-cultural milieu. The problem is that at too early a stage, conclusions are made that impose deductive dogma. When such dogma is widely embraced, falsehood may follow upon falsehood with no efforts to reassess new evidence in light of current understanding. When a dermatologist looks at a rash, he methodically runs through the features of size, shape, color, borders, numbers, etc. Only then can he categorize the rash and make a likely diagnosis. The newbie medical resident will say "it looks like..." and often misdiagnosis and mistreat. I am training myself to look at tsuba without dogmatic biases (I disregard supposed schools, styles, categories, or certificates) and by focusing strictly on features (size, shape, thickness, surface treatment, execution of rim and hitsu-ana, composition, overall sense of power and appeal, etc). More and more I am seeing that strict attribution isn't possible for mumei tsuba produced after Early Edo because there is just such a mixing of styles and techniques. The provincial styles are no longer clearly evident. I recently posted a Kanayama tsuba from the Momoyama period that has a massive seppa-dai more characteristic of Ko-Shoami. Works for me...2 points

-

2 points

-

I recently acquired a nice gunto with a damaged tsuka - to the extent that the sword would not lock up in the saya. So I decided to repair it. The fittings on the sword are high quality and they are all original (and matching numbered). There are 4 seppa on each side of the tsuba; another sign of quality fittings IMHO. I will post pics of the fittings at some point; for now - lets concentrate on the tsuka. Here it is removed from the sword and the ito moved out of the way to expose the damage. Basically a chunk of the wood and rayskin on the outside (omote) is gone so there is nothing for the latch (chuso) to lever against for locking up. The inside (ura) of the tsuka is in fairly good condition. outside side inside ura side After I examined another tsuka I thought that the best approach would be to restore the missing wood. I made a repair piece whose profile matched the missing wood. I also added two small pieces of wood - on the front to prop up the chuso spring and another to reinforce the back for where the hole for the the mekugi (peg) will be drilled later. These were glued on. The replacement wood was fitted as closely as possible to match the missing wood... I first glued the repair wood in place and drilled/reamed the hole for the peg. I also glued a strip of fabric to the end of the tsuka to take up loose of the fit of the fuchi. One thing I learned is that fine adjustments are necessary to restore the functionality of the lock (chuso). You have to observe how the parts interact (or should interact) and adjust as necessary. Here is the tsuka with the repairs At every step I would test fit the parts and also try to see if the chuso would latch properly into the saya. Here was something that I had to figure out. This is the fuchi (end cap for the tsuka) that has the chuso installed. I wondered if the spring rests in the square "hole" or if it sits against the blade. It needs to lever against something afterall. I decided that the way it worked is that the spring rests inside the hole and uses it to lever against. I took a long time trying to decide if this was correct or not. (I also had to bend the spring back to its proper shape as it was bent way too much to compensate for the damage...that took a long time to correct.... I tested the fit and found that the chuso would not lock up so I made a number of small adjustments. First I noticed that the part that locks into the saya was bent; I very very carefully straightened it out (this took a number of tries - using a vice and tapping it with a small hammer (the metal bends very easily). After testing again, it still would not lock although it was closer... I then noticed that there was a gap between the wood and the fuchi right where the chuso spring rests. See that little gap- I had to fill this in! With what?? So I decided to fill the gap with cryo (super glue) reinforced with baking soda powder. After filing it down to shape... (pic not in focus) Here are pics showing the parts assembled for test fit. The pic below show the chuso (latch) sitting above the rayskin; it must be below the level of the rayskin like below. I determined that only the rayskin holds the latch in place - you would think there would be wood or something else to hold it down... It took a lot of fiddling with the fit of all the parts to get the latch to have enough tension to lock when its below the level of the rayskin (I'm putting slight pressure on it below) Now, the parts align and the latch seems to work! On to the repair of the missing same (rayskin) TO BE CONTINUED1 point

-

When there are multiple Mei for an artist that is not particularly well documented, they are generally grouped into different "generations", Shodai, Nidai etc. Generally this is done on the basis of perceived quality or mastery. I believe that this is an erroneous assumption that has more to do with Japanese hierarchical social conventions than logic, and that generally there is no evidence to determine which artist was the founder or primary artist and what order they worked in.1 point

-

1 point

-

I started collecting early sukashi tsuba in March this year. While nearly all of the eight excellent Kanayama, Owari, and Ono tsuba in my collection come with NBTHK papers, even if they were not papered, I would still have acquired them on the basis of my own extensive study and with the guidance of mentors from this community. Hozon and Tokubetsu Hozon certificates have added nothing to my decision-making. I don't foresee any instance in which I would send a tsuba for shinsa in the future. There is a tsuba recycling on Jauce that is papered separately to both Kanayama and Ono. It clearly isn't Kanayama. If it's Ono, it is very late Ono at best because the motifs and the composition are too contemporary (anchor, Tochihata style rope-like mimi). I didn't need the papers to tell me this. On the other hand, two of my tsuba are published (one in Sasano's gold book, the other in Owari To Mikawa No Tanko) and a third tsuba is nearly identical in style and composition to well-documented examples in the literature (books and articles). I find published pieces to be of value because the high level of scholarship behind them adds to the depth of my knowledge, appreciation, and enjoyment. Additionally, published pieces tend to be highly curated to showcase the finest examples of their kind. That establishes monetary and historical value. This is not to say that there aren't mistakes in even highly revered publications. A tsuba that has long been offered by a seller is papered to Akasaka, but a nearly identical one is published in Sasano's silver book as Ko-Shoami. I think it is actually Owari, although the close relationship between these styles points to the possibility that it is a product of the workshop of a Ko-Shoami master in Kyoto whom Eckhard Kremers hypothesizes to be none other than Kariganeya Hikobei, the elusive and mythical influence behind prototype early Akasaka style guards. So, attribution to Ko-Shoami, Owari, and Akasaka may all be correct if we are considering this from the perspective of a master smith who is actively engaged in the evolution of his art. Are we having fun yet?1 point

-

This swords keep making the rounds (it has been posted to Reddit, Facebook, etc and I continue to receive inquiries from collectors asking my thoughts). 1. this is a torokusho, a license document and does not authentic the mei in any way. https://www.jssus.or...nese_sword_laws.html 2. the nakago looks very much like one that was o-suriage, and has had a mei added and the nakago reshaped to look like an ubu, Soshu, tanagobara nakago (consistent with what you want to see from a mei of Masahiro) 3. as far as 'susposed to be Tamahagne", yes it is likely that any antique Japanese sword is made predominantly from traditional materials. I would not base a buying decision on that fact, it's simply what it is and you don't need to generally worry about whether traditional materials were used until you start differentiating between WWII era gendaito and showato.1 point

-

Awesome examples, Dale! Thank you for all these. It's also good to know some of the common fakes. I particularly like this one that I've quoted from you above! Coincidentally I have a vintage frog themed collection. Just little things i've picked up over the years shopping antique stores. Some frog tosogu would really be the cherry on top! Cheers, -Sam1 point

-

Omi Daijo Fujiwara Tadahiro https://hizento.com/...eration-tadahiro.php1 point

-

近江大掾藤原忠廣 - Omi daijo Fujiwara Tadahiro1 point

-

近江大掾藤原忠廣 Ōmi Daijō Fujiwara Tadahiro (Made by Tadahiro Fujiwara, Lord of Ōmi Province).1 point

-

Three Kanayama - - 0ne Owari - I am no expert but they look very hard to tell the difference? This one is described as Yagyu - but if we are judging surface texture or the cut of the mimi - good luck with that in this condition!1 point

-

That is only in Japan where it isn't common to find them registered as they are regarded as non-traditional. Eveywhere else they hover around 2-3K usd.1 point

-

Awesome examples and quotes everyone!!!! I would suggest that this clearly points to the idea that thin, large ko-katchushi, ko-tosho and what would would call the "Saotome kiku style" (chrysanthemum pattern) already had some sukashi elements at this point and were the already established norm ie. the "old style", while smaller thicker sukashi tsuba like Owari and Kanayama would likely be the "new type" at this point in time. This passage from a text from that time period is a massively significant find actually These are both significant pieces of evidence that support the idea of the emergence of simple ji-sukashi tsuba in the late Muromachi, and the emergence of the smaller thicker type of more expressive ji-sukashi during the Azuchi-Momoyama period. All of which fits very nicely with the socio-political events of the time.... Nanban influence from Europeans (seeing openwork guards for the first tuime), switching to wearing katana rather than tachi (making the tsuba more prominently displayed), all under a broader umbrella of a period of exploration and expression of individuality among the samurai class who were rising to prominence, as well as the samurai class immersing themselves in tea culture and all its associated philosophical concepts (which can often be seen in the themes and aesthetics of early small, thick ji-sukashi tsuba). ... It looks to me like we're quickly building a pretty decent convergence of actual evidence and theorizing on this particular time period beginning around the mid-1500s (late Muromachi). Again though, I'd happily move the date back to the 1400s... so long as some concrete evidence shows up Although, moving it back would then require finding some justifiable socio-political reasons for this significant shift in the style of tsuba production. So far the only one I have read (from Sasano), is that "a variety of arts (primarily painting and calligraphy) were highly prized during the Muromachi period"... although it's important to point out that this was primarily among the elite upper class and highest ranking among the warrior class, but not so much among the general warrior class under their employ.1 point

-

Hi Brian, One of the challenges for iron tsuba connoisseurs is in attempting to differentiate the genuine early (pre-Edo) iron guards -- especially those attached to famous names (e.g. Saotome, Nobuie, Yamakichibei) -- from those made in the mid- to late-19th century during the era of Bakumatsu revivalism. This period saw quite a bit of enthusiasm for returning to the glories of Momoyama times, and this manifested in many efforts among the sword guard makers of the day to pay homage to those illustrious tsubako of the past. I don't have much specific knowledge on the Saotome, but it is not difficult to imagine a late-Edo Saotome smith harkening back to "the good old days" in creating a tsuba meant to express those aesthetic sensibilties. I'm not saying your tsuba is certainly a 19th-century work, as I just don't know. But it is worth remembering that a lot of 19th-century works were made to try to capture the powerful iron expressions seen in the tsuba of nearly three hundred years earlier.1 point

-

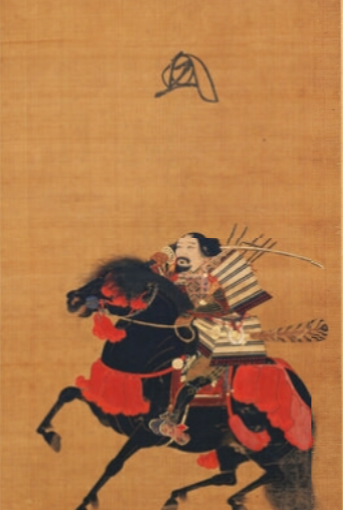

This is extremely good idea to open up these topics. Unfortunately koshirae is not my field so I cannot add much insight to the discussions. I tried to find specific koshirae examples that can be traced to specific individuals but there are actually only very few of the really old ones pre-1600, and the remaining ones are often to some very famous people. I personally love shrines and temples in Japan and romanticize their items. Often swords donated to them have remained unchanged for long time periods. Also the battlefield ōdachi and naginata/nagamaki were pretty much useless after wars in Japan ended, so many of them have remained in shrines in their koshirae. Now I have been fortunate to see many ōdachi at various shrines in Japan, and also many ōdachi koshirae. I would agree that the ōdachi tsuba in general are really plain. Mostly just metal or leather plates, there are few that have the boar's eye cut outs in corners as you mentioned in the opening post. Unfortunately I don't have photographic memory but I don't think any of the ōdachi koshirae from Nanbokuchō or Muromachi period I have seen in person had large sukashi cutouts. Also one thing to note that artists in the period might not know the actual swords 100% correctly. Atsuta Jingū owns the two famous massive ōdachi Tarōtachi and Jirō Tachi, and were wielded by Magara brothers/or father&son (if I understood the legend correctly) The smaller one Jirō Tachi 166,6 cm blade was I believe by legend wielded by Magara Jūrōzaemon (真柄十郎左衛門), and there is a famous painting in which he wields the ōdachi on horseback at battle of Anegawa 1570, where he died. I think Jirō Tachi was dedicated to the shrine shortly after battle by the victorius side and Tarōtachi bit later in 1576. Here is the painting and it has similar open wheel tsuba as in the painting discussed earlier. https://en.wikipedia...i_sword_on_horse.jpg Someone has taken pictures of Tarōtachi. Here is the current koshirae. Now in one book there is a text passage about these koshirae but I cannot yet read it correctly. https://static.wikia...00?cb=20150919175256 Atsuta Jingū also has 3rd ōdachi with similar koshirae that was made in 1620, it has 144,5 cm blade and it has 17,5x17,0 cm tsuba that is dated to 1620. So obviously this was later than the 2 famous swords but as it features the same koshirae style it could have been made to honor the famous swords. Unfortunately photography is always forbidden at the shrines so I do not have any pictures. Sorry for going bit off topic with this as it was not exactly on topic but illustrating how difficult it is to prove something with certainity. I agree the tsuba I posted a picture of might not be Nanbokuchō period, just that Japanese experts have possibly agreed on that as it was featured in publication. I do think shrines and temples are the best places to discover original and unaltered items, of course they might often not be that desirable by high end collectors.1 point

-

@Curran here's a simple rebuttal...no need to invoke Darcy If the master of the technique himself, Haynes, can use that method and wrongly misjudge the dating of a tsuba by 200 years, proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that this is an unreliable technique. I'm hoping we all move toward an approach that uses more reliable evidence. There are too many obvious flaws in using this particular method. You are of course entitled to your own beliefs and I won't judge you for it1 point

-

The original contains the kaō of the second Ashikaga shogun, Yoshiakira, and the image was supposed to have been that of the first Ashikaga shogun, Takauji, but lately there is a line of inquiry that says the image is that of Kō no Moronao or his son. In any case, mid 1300s. source https://emuseum.nich...&content_pict_id=0021 point

-

Nice one Thomas I couldn't agree more. It's definitely based on a Japanese social construct. I think in some cases the order should be re-evaluated into a more logical "progression of development" rather than the perception of "best first". ... and to make matters worse within the existing system, "best" can sometimes be subjective1 point

-

Interesting question Judging by how many koshirae have guards that are not original to that koshirae. As in stuff like seeing a saya with no space for a Kogatana but tsuba has the hole. Would say it was only the well of that would have tsuba made, guessing there would be buckets of old spare tsuba knocking about. If you find a good one that fits, why buy new. If you were having new swords made then i suppose you would have newkoshirae/ guards made. Just thoughts, don't know the price lol.1 point

-

You know, this is one of the areas where AI could be useful. I know a company that has a learning AI that can now identify the types of fracture when fed microscope photos of failed metal pieces. It's also in the vein of big data: scan as much as possible and use scanning models to see trends appear: what texture is preferred, are there specific designs that appear, size, etc. An issue in this is the dating. I did not know about the school names being set later than the production era for sukashi in general, but for tosho and kachushi, Mr. Ogasawara and Mr. Katsuya did write that while attractive, the names meant nothing and there was not one shred of evidence that the tsuba were made indeed by swordsmiths or armourers (although Prof. Michel-Tanaka did tell me that his swordsmith acquaintance was making tsuba essentially in the tosho style; but I have no idea if this is a transmitted thing or if he made it to fit the category).1 point

-

How long is a piece of string? How much is a car today? How much is a house today? How much is an education today? They are what you can afford, and there should be something for (almost) everyone. One counter for “a suit” of armor is “Ichi Ryō” 一領 It is said that “ryō” means residence or domain, according to one explanation, i.e. it could cost the price of a plot of land and a house.1 point

-

Humans like to put things in neat little boxes, collectors like to know what they have and covet things that are rare, important and/or have artistic merit. The NBTHK provide a service to help categorise and sort objects, there is a general consensus that they are in the best position to provide this service, there are clear rules and most collectors accept the categories and rankings. It is a game that most people accept and play, many collectors have a vested interest in the system and maintaining favourable attributions and I do not think there will be any significant shifts in the near future. That said there is vast gulf of information about Tosogu that is just not known and may never be known without new research and evidence surfacing, particularly for items pre-dating the Edo period. I agree that the categories used are often quite lose, sometimes totally illogical and are not adequately supported by sufficient evidence. I think the primary issue is that most people take the attributions at face value, without much thought, not realising that many of the categories are nothing more than groupings and educated estimates.1 point

-

For the story of super high-end tsuba and fittings look here; https://nihonto.com/nakai-koshirae/1 point

-

1 point

-

What you have appears to be a shinto blade (from the early Edo period) in shingunto koshirae (army mountings). What I would say immediately is that there's nothing that you should do to remove rust, and whether or not any of the patina on the nakago (tang) has obscured the signature no rust should be disturbed in any way from that area. The nakago, it's patina (color and texture), is a vital characteristic that should be left completely unaltered.1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

This leaderboard is set to Johannesburg/GMT+02:00