Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation since 05/06/2025 in all areas

-

Dear All I hope this finds everyone doing well? 48 hours ago I was greeted with the wondaful news that the NBTHK Japan has given us permission to share the English Versions of the NBTHK magazines from series #1 to #58 (ONLY) here on the NMB for educational purposes. Conditions are: - The Magazines cannot be sold to the public or board members. They must remain as free educational material. No profiting under any circumstances. - There must be a stable record of how many members are downloading the magazines (we already track the download numbers) - These are for the English magazines from the late 1970's and only numbers 1 - 58. - The NBTHK Japan must be acknowledged as the original publishers. This has been weeks in the making with 2 close contacts in Japan lobbying on our behalf and they really have come through for us so I have a lot of making up to do for them when I am next in Japan. I shall send everything to @Brian and allow him to upload them when he has time. Thank you for your patience everyone and I hope that the materials will help your education and collecting journey as much as it has helped so many in the past.42 points

-

Excellent blogs by other people, first and foremost Markus, have inspired me to being releasing a newsletter. Three topics each issue, each something not well covered by books. In this one you can find articles about: Kyushu nihonto Saiha and yakinaoshi - same of different? The true meaning of NTHK scores https://www.historyswords.com/news1.pdf25 points

-

Folks, an interesting but undocumented Seki swordsmith. Be good to find out who he was. I have compiled what I could find and tried to make some sense of it. Would welcome comments, corrections and ideas. Following are my notes and pics. UNJOSAI KATSUNAGA 雲上斎 勝永 An apparent mystery with wartime Seki swordsmiths is Unjosai KATSUNAGA, who produced a wide range of blades, but for whom no records were found (so he is reported as “undocumented”). He is not in the 1940 Seki City lists and is not in the Seki swordsmith registration list from 1939. His blades look to be both Showato and gendaito, most are mounted as Army shingunto in various fittings, there are some Naval kaigunto and at least one in wartime civilian mounts. A number are in post-war shirasaya or have been mounted for iaido. He has a number of mei, which may reflect types of swords produced. Katsunaga 勝永 (H, O) Unjosai Katsunaga 雲上斎勝永 (B, C, D?, E, F, G, M) Seki Unjosai Katsunaga 関雲上斎勝永 (A, J, K) Unjosai Katsunaga saku 雲上斎勝永作 (L) Unjosai Katsunaga kitaeru kore 雲上斎勝永鍛之 (I, P) Katsunaga saku 勝永作 (N) In regard to his mei, “Katsunaga” is his swordsmith name, however, “Unjosai” is probably not a family name and more likely is a “go” or pseuydonym/penname. “Katsunaga” is said to be a masculine name and there were several noted samurai of the Edo period with it. There was also a samurai in the 1800’s, Sagae Chuzaemon Katsunaga (1806-1864) who became a swordsmith in Edo Tokyo and was of the Mito Domain, Ibaraki. So what would be this Katsunaga’s family name? He signs as katana mei, but with variations. Showato blades are signed on the shinogi-ji with a “chippy” cut style (nakirishi mei) that reflects mass production work. Those with well cut mei reflect custom work and are larger characters and centrally located over the nakago shinogi. Mei on custom blades have both a neat formal style, and an artistic cursive style; one variation is of vertical “squarish” characters that are deeply cut using “interpretive” kanji (N and O). Possibly the custom blades are signed by the tosho (shoshi mei). Only one blade (J) of the examples found has a stamp reported, which is the large “Seki”. One example (A), has a bohi-hi kaki-toshi groove through the nakago; this blade is both neatly finished and signed and could be semi-traditional. The shape of the nakago also varies, with different amounts of taper and several styles of kiri tip; some with ha-agari Seki type, others slightly angular. The yasurime filing is angled sujikai, with varying degrees of neatness; on some blades there is a criss-cross hagaki section (but possibly just rough work). Differing hamon were found. The Showato examples tend to be more of a Seki style midare-gunome (A, D, F, H, J, M) some are slightly notare. It appears that the better made and custom blades have suguha hamon (G, I) some with nie-deki (I). No images were found of the other custom made blades. The typical blade has an average nagasa of 63.0 cm (61.7 to 64.5 cm) and small sori of 1.0 to 1.2 cm. Several blades vary from this: C: this is a custom blade of 67.4 cm length and sori of 1.8 cm. D: this is a longer blade which is shortened around 10 cm to 52.7 cm (wakizashi length) with the mune moved and a new nakago ana drilled; the mei is also shortened. The blade has been remounted in shorter shingunto koshirae. I: this blade has a nagasa of 64.3 cm, however, it has two mekugi ana and is probably shortened by around 7-8 cm. The mei is below the lower hole and kiri nakago tip indicates the shortening. The suguha hamon on this sug-gests water quenching. Of note, it is in wartime civilian mounts. Basically there appears to be three types of swords: (a) Showato oil quenched Seki work suggesting some form of mass production. (b) quality Seki work possibly semi-traditional with hand forging/folding and neat finish. (c) top end custom orders, traditionally made and on request with name of client. Of interest is sword K which has a label on the saya of “The Seki Cutlery Manufacturers’ Association” and “Seki Gifu Japan”. The label shows “Passed” presumably approved for sale. The nakago of sword K is a little rough, no stamp is obvious; these labels look to be used mid to late war, however, are mostly found on “budget” swords with basic wooden saya. The mei of sword J is the same as that of K, both stating “Seki”, and possibly has a similar hamon. Nagasa for these are K of 61 cm and J of 62.8 cm. Overall, production of Katsunaga blades suggests a smaller workshop, or several workshops, linked to a sales outlet, with a number of craftsmen involved; the various styles of mei are likely by different people. The examples here show Katsunaga was a Seki smith, and he does look to have some training as a tosho, however, he is not in the Seki registration list. But who was he and what was his name. There must be a record somewhere. Malcolm Cox, 202516 points

-

If you ever wondered how many swords you would have been able to study if you had attended every single monthly NBTHK main branch meeting the last 25 years, here you go: https://markussesko.com/2025/05/12/nbthk-kanshokantei-blades-analysis/14 points

-

Yip...awesome work by Rayhan, and a huge thanks to the NBTHK for allowing this. I will be uploading them into a special section in the Downloads section over the weekend, and it will likely take some time to get through all of them. Really excited about this. There will be a disclaimer to agree to when you download, to prevent commercial use etc. The downloads section is for members only, so hopefully this will also encourage some of the lurkers to sign up. Only requires a free membership, no subscription needed. Info like this is invaluable to collecting, and I am grateful to be able to facilitate this. Thanks again to the NBTHK, Rayhan and those that worked to make it happen.13 points

-

9 points

-

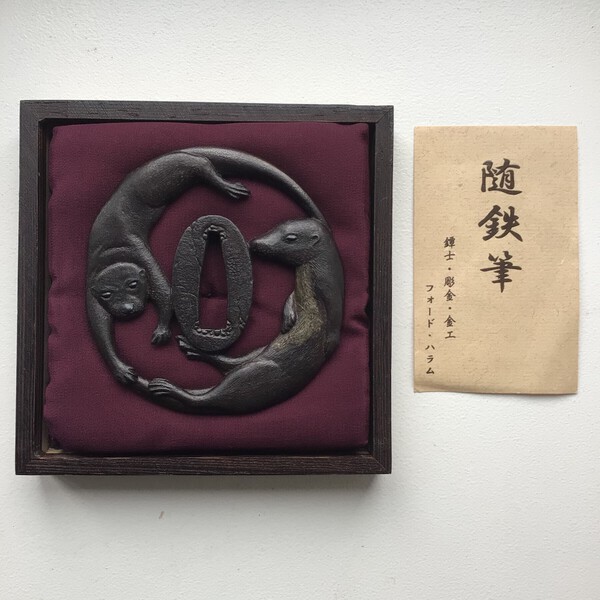

Flamingo Tsuba by Ford Hallam. I acquired this in 2017 from a Finnish collector who had bought it from mr. Hallam. You can still find photos of the item in Hallam's Facebook page "Following the Iron Brush", go to photos and scroll down. Kinko 80mm x 76mm Mei is the one he used before going to Japan, so it's a combination of "F" and "H". As this is his old signature, I guess you might call this one a Ko-Mr.Hallam I have been inactive in this hobby for quite a while now and I think this tsuba would be better served in an active collection - to preserve his memory. Comes with a nice pouch! Price: 1500 USD / 1343 EUR + shipping. I'm based in Finland. If you need more photos, just ask! I have forgotten some of the terminology, so hopefully I got everything right.9 points

-

9 points

-

Yep. Helps when they are signed. Sometimes the signature is faint, like on this Yamakichibei below. I was excited to finally land a signed Saotome the other week. It is probably the last thing I will buy out of Japan for a while, until the tariff and related shipping issues get minimized. Will post an image of the signed Saotome when I get it.9 points

-

Attic junk. Up in the loft (attic) of a Japanese farmhouse I found the remains of two dusty old lanterns. The owner said she didn't want them, so reckoning I could fix them up I asked her not to trash them. Nothing really special: one was a simple box frame, unpapered, with a central spatula or tongue for a candle. The other was better, with three papered but torn windows, a door with a little catch, and a shrine-like roof. Being an earthquake prone country, with houses made of wood and paper, you can understand the traditional nervousness around the danger of fires. Off the scale, what I came across when first living here. I do not plan to put real candles in them, unless following the golden rule of never leaving a room empty with a burning light unattended. Take the light with you (to the 'habakari' for example), or light a small carrying lantern and extinguish the main light. If you are the cause of a house fire, the whole village will probably hate you forever. With these two as a temporary fix, I have simply fitted Buddhist altar lights, candle look-a-likes with batteries! As to age, they probably do not go back to the Edo period, but who can date such country traditions? The loft was once used for silkworm culture, but that must have been way before WW2. Photos to follow. (Both lamps strengthened and rebuilt.) 1. The box frame. Maybe I will paper the facets. 2. The roofed shrine lantern.9 points

-

I'm leaving for Berlin tormorrow to bring the blade to the NBTHK-EB meeting on Saturday. For the non NBHTK-EB members and those that can't make it to the meeting, there is a written (borrowing) agreement that my blade will at the Samurai Museum Berlin. It is planned to be put up on display starting 23rd May 2025, and approximately one year. Hope that this will allow fellow members to get to look at it in person. And keen to hear what you mayever think of it, if you manage to see it, either at Museum or at Saturday's NBTHK-EB meeting!9 points

-

Here are the amount of swords NBTHK has had passing through each phase of their shinsa. The numbers are not 100% correct but in the quite close neighbourhood and they will hopefully give you lot of insight. Starting from highest tier to lowest Tokubetsu Jūyō - c. 1,200 swords Jūyō - c. 12,000 swords Tokubetsu Hozon - c. 80,000 swords Hozon - c. 125,000 swords I am quite sure there are 2,000,000+ swords in Japan. I made a post about license numbers as it is a running system and you can see it here: https://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/52155-naginata-naoshi/page/4/#comment-545277 The problem with running systems is that if the sword leaves the system (for example advances to tier above in NBTHK system) it just remains in the system as number even though the actual sword would not be Hozon papered anymore. Similarily if the sword returns to the system it gets issued a new number (sword gets a new license number when it returns to Japanese system, or for NBTHK shinsa the sword gets resent for Hozon and it gets a new paper and different attribution). Unfortunately these are the closest numbers that I can get. About the pass factor, I chose 2 sessions slightly randomly as they have pretty much the same number of swords sent in. And I do own books for both of the sessions so I have data on every sword passed. Jūyō 68 shinsa had 817 swords sent in to the evaluation. Out of them 66 swords passed. With my math that would be 8,1% pass rate Jūyō 25 shinsa had 819 swords sent in to the evaluation. Out of them 341 swords passed. Using the same math it would be 41,6% pass rate Pretty big difference... In the 2000's I think the pass rate has mostly fluctuated between 10-20%. There are some below that and some above that. It seems like the most recent ones 68,69,70 have all have been judged very stricly with very small amount of swords passing through.9 points

-

8 points

-

Exciting News! We’re thrilled to announce that Markus Sesko—one of the world’s leading Nihonto scholars and authors—will be offering mei assessments at the Orlando Japanese Sword Show on Saturday, June 21st! Got a sword or tsuba with a signature you're unsure about? Wondering if it’s worth submitting for shinsa? Don’t risk your hard-earned money—Markus will be on hand to help separate the genuine from the gimei. 📅 Show Dates: Friday, June 20 through Sunday, June 22 📍 Just minutes from Orlando International Airport, with easy access to Florida’s top theme parks. This year’s show features: 40+ vendors with swords, fittings, and antiques for sale Demonstrations and workshops, including an immersive session on Japanese calligraphy, oshigata-making, and tsuka-maki Bonsai and ikebana displays Tsuba show & tell And now, mei checks by Markus! Markus will also give a special talk during our Yamashiro sword exhibition and will be happy to sign exhibition catalogs and copies of his books. So, whether you're a seasoned collector or just starting your Nihonto journey, there’s something for everyone. For more information about attending, booking a room, or reserving a table, please contact organizer Mark Ceskavich at: 📧 orlandoswordshow@yahoo.com NO FOMO! Don’t miss this incredible weekend. We look forward to seeing you in Orlando!8 points

-

8 points

-

8 points

-

Buy both. Worry about how you'll afford them later. You'll always find a way. Never regret buying something you want, otherwise what are you working your whole life for?8 points

-

This powerfully formed katana is the work of Takano Masataka (real name: Takano Ken'ichi), forged to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Meiji Restoration. Masataka, active during the Shōwa period, was born in 1891 in Ōme, Tokyo Prefecture. He was a disciple of Sakai Ikkansai Shigemasa. MASATAKA (政賢), Shōwa (昭和, 1926-1989), Tōkyō – “Bushū Mitake-sanroku-jū Masataka” (武州御岳山麓住政賢), real name Takano Ken´ichi (高野賢一), he was born November 5th 1891 and studied under Sakai Ikkansai Shigemasa (酒井一貫斎繁政), he lived in the city of Ōmi (青梅) in Tōkyō Prefecture This blade is a powerful piece in the Sō-den Bizen tradition, evoking the dynamic style of Chōgi. The blade is in polish with a high quality shirasaya and fitted with a beautifully executed gold-wash habaki bearing a kamon. $7,250 + shipping & PP8 points

-

8 points

-

8 points

-

Hi All, Greetings! I want to share with you all my most recent Gendaito purchase. Below are the specifications of the blade, please leave some comments, and ENJOY!!! BUSHIDO Akamatsu Taro Kaneyuki (Homemade Iron Forging) Nagasa Blade Length: 73.8cm Sori Curvature: 1.9cm Width at Hamachi: 3.37cm Width at tip: 2.45cm Moto Kasane: 0.74cm Sori Kasane: 0.42cm Blade weight: 770G 2013 Year of the Snake I love it, the balance is great. Right above the Handle. Should be great for Iai / Tameshigiri7 points

-

This summary attempts to clarify the variation in kanji used for Showa period tosho namde KANEKUNI and the duplicate use of family name OGAWA by different Seki smiths. These variations can be confusing in the translated literature, especially the kanji for “Kuni”. Hopefully, there are no errors in this paper! Available in NMB Downloads:7 points

-

7 points

-

7 points

-

Flexing my moderator privileges, and deleting the off-topic back-and-forth arguments. Let's keep name calling off the forum; whether that be in private message or public. Let's stick to the topic at hand, and remember why we're here. Differences of views/opinions/experience and observations is no excuse for hostilities. -Sam7 points

-

7 points

-

陸奥守綱宗 – Mutsu no kami Tsunamune A real daimyo who enjoyed making swords. Ref. Date Tsunamune - Wikipedia6 points

-

Hi all. So I ended up buying the sword you guys helped me to identify as real kai-gunto. I took some pause to cool off and think. Then I contacted the seller and negotiated the price down to USD 1500. Still sounds like a high price for such a sword, but I had reasons of my own to buy it. The main thing in a situation like this is to be happy with what you get. And so far I am happy. I believe I already mentioned that after three years of war I grew tired beyond measure and in the last months I feel myself completely burned out. Yet I still have work to do. Luckily, these days I have some time (not much though) I could spend on myself. And since I found out that Japanese blades have a magic in them that switches my mind in no time, I am in it. After the first failure (though I don't consider it as such) I decided to switch on simpler things like Navy dirks. And since for me the best way to study a subject is to have some objects of study at hand I acciered a pair of them. But I believe it may be a separate story, so let's return to the kai-gunto. Sword arrived and as expected: the blade had some corrosion dotting and it barely had a place free from fingerprints. And as you guys correctly noticed, nagasa was buffed. Fittings looked like they were in dire need of cleaning. At first glance the sword looked like an assembly: tsuba and seppas may be from one set but nakago-ana is too large for this blade. Luckily for me, I have some experience in polishing metals (though, not swords) so after looking at the blade I had a clear understanding that any kind of improper treatment will do no further good. So since its arrival I was only constantly oiling the blade and the most aggressive tool I used on the nagasa was a toothbrush with shortened bristles. However, I gently cleaned habaki, tsuba, seppas, fuchi, locking mechanism, kabuto-gane and sarute. I had no time for cleaning the elements of saya yet. Now kai-gunto looks like this. Process of cleaning was closely monitored by one of our cats. She likes to participate in all kinds of human activities. That's why some photos are more hairy than others:-))6 points

-

Motte sabinai tetsu saku kore Kanenaga Kanenaga made this from stainless steel. (On the wood habaki it also seems to say Kanenaga)(?)6 points

-

6 points

-

Slightly unusual in structure, so it's a bit hard to parse. Anyway, the vertical writing is 祝 (congratulations), 歓送 (congratulatory send-off) and then the word 近衛 (Konoe) which is a rather noble family name, but also a word used to describe a guardian of the court. I don't think its meant to be a name here. Maybe its use is intended to be patriotic, or invoke a martial spirit. But it seems slightly weird to me. Under that: 應集 (a word used to assemble a group, sort of like the military command to "fall in") 勇途 (another word to invoke a glorious send-off of a brave person). Then we have what should be the recipient's name, but I can't quite get it. Maybe 津寅之助 (Tsu Toranosuke)? Anyway, its somebody Toranosuke. Then on the left side is the writer's name (I think) Shimazu Hatamata, although I'm not 100% sure of this. The two kanji at the top of this name might be a location name (Sata? Yuta?).6 points

-

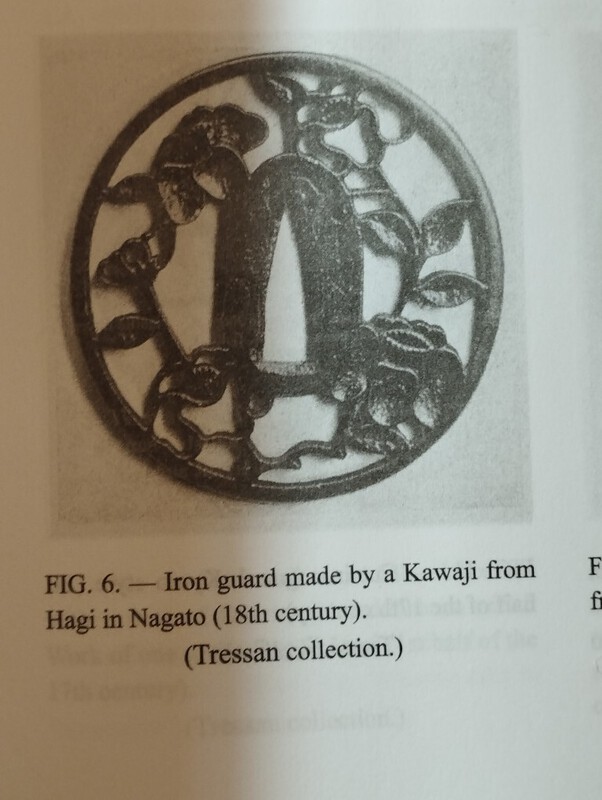

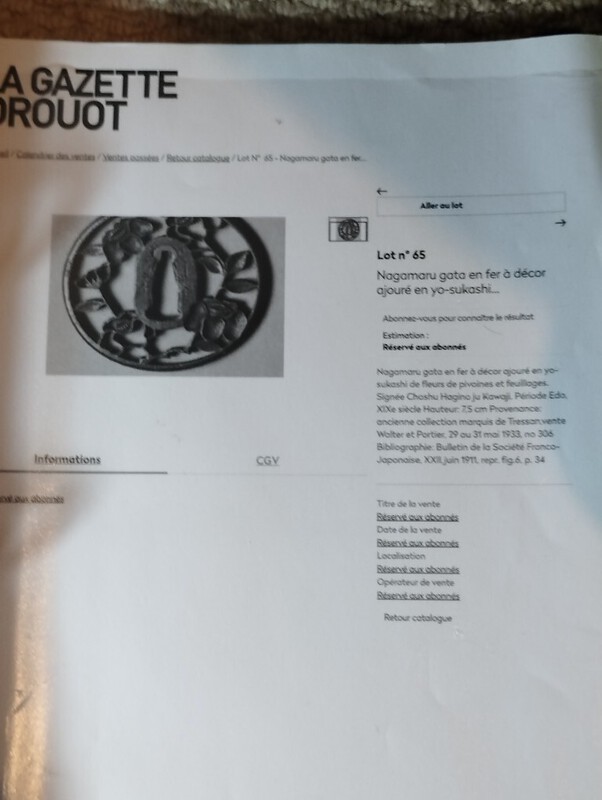

This may be of interest to Spartan Quest as during my research l found this tsuba in his recent book, Additional Early Articles for Tsuba Study 2. This tsuba was published in the Marquis de Tressan's 1911 Bulletin of the Society Franco Japonaise, the Evolution of the Japanese sword hilt from the beginning if the 17th century to the present day. I purchased this at Bonham's Samurai Snow auction but at the time the auction house did not have details of provedance. It was only after researching an auction tag on another tsuba that led me to a site citing this tsuba came from Tressan's collection. The Marquis was killed during the First World War in 1914 but the tsuba was not auctioned until 1933. lt would be interesting to know who owned this tsuba from 1933 to 2024. There is a vary similar tsuba (number 218) in The Hartman Collection of Japanese Metalwork (1976), but this is described as a daisho set and the seppadai appears different. Neil B.6 points

-

6 points

-

於江府長運齋綱俊 Oite Efu Chōunsai Tsunatoshi 弘化二年二月吉日 An auspicious day in February, 2nd year of Koka (1845) Edit: More information here: https://nihonto.com/tsunatoshi/6 points

-

Just for clarity i was never a student of Ford, except watching his tutorial videos on Youtube i had no relationship with him, i'm pretty much self-taught6 points

-

Kuchibeni - 口紅 - A speciality of the Suruga school [not the same school as the tsuba in question]. This school is known for 'kuchibeni' or copper sekigane at the top and bottom of the nakago-ana which were placed at time of creation and are not a sign of refitting (kantei point). These were also seen in the later Edo work of the Tanaka School. Those on Jason's example look untouched (rare) and an indication that this piece was fitted only once to it's original sword. As I hope you can see from this slightly grainy image the Kuchibeni were installed in the nakago-ana before it left the tsubaco. Kuchibeni are generally a mark of good quality pieces and like this image they were often fitted with no gaps or protrusions. I also agree with Justyn that the nanako-ji is far too good to be cast. https://jameelcentre.ashmolean.org/collection/7/10237/10353 Check the kuchibeni on many of these Suruga school pieces - they are often altered later to fit other blades. There are indeed many fake or "reproduction" tsuba with fake sekigane but very few with Kuchibeni - Why? well they want the sekigane 'noticed' and good Kuchibeni would be almost invisible if it were the same colour as the rest of the guard.6 points

-

The simple answer Ken, is, as with Nihonto, you can tell at a glance, if you've spent any time with them in hand and studying with books. There are also websites dedicated to pointing out the differences. The difficult answer I will attempt to answer below. It is worth remembering that at any antiques fair you will find hundreds of NLO, but rarely a Netsuke with both fine quality of carving and serious age. There is some middle road with funky (民芸品 Mingei-hin) folkcraft netsuke used in everyday Edo-period life by ordinary people; these can have an old rustic charm of their own, and if you are lucky you can still find them at antques fairs, hiding within collections of more modern NLO pieces. As I said above, everything. The opaque white of the material reminds me strongly of resin 'netsuke' produced recently for museums, or in sweatshops in China, although it could be marine ivory. I cannot see clear Schreger lines, except possibly in the tail, but there are nerve-ending holes fore and aft. The strength and application of the stain. The casual hairstrokes, the crudeness of the carving of the paws underneath. The rough treatment of the himotoshi holes, and the final straw is the obligatory Japanese-looking Mei. All of these shout NLO. Having said that, I do not wish to shock the starter of this thread, as it is indeed a cute object, and many people collect these happily. Over on the International Netsuke site we get a steady steam of people who say their grandmother left them a precious collection and can we evaluate it. Well, sadly, no. (By the way, there are modern genius artisans who produce one-off works of supreme art. Such netsuke are another complete area of collecting, but they can justly be very expensive.)6 points

-

A very fine Machibori Tsuba made by the 5. master of the Otsuki school – Mitsuhiro. MITSUHIRO 1795 – 1841 Hamidashi Tsuba, Mei (Kishotei Mitsuhiro und Kao) 5. Master Otsuki School Family: Otsuki Name: Gihachi Gozaemon Artname: Kishotei, Dairyujo and other Livingplace: Kyoto Mitsuhiro was the son of Mitsuoki (4. Generation). His father (Mitsuoki) was one of the top three Tsuba artists from Kyoto at this time – beside Ichi-no-Miya Nagatsune and Tetsugendo Shoraku. Mitsuhiro too runs the familyshop under the name „Yamashiro Ya“. In th age of 45 he became a priest and used the artname „Soju“.. Mitsuhiro was specialized in the use of patinated brass an copper like his ancestors. He is rated in the Kinko Meikan as Jōkō. Haynes H 05188.0 We can find works by Mitsuhiro: Japanese sword fittings from the alexander G. Moslé collection, P. 98 Nr. 140 100 selected Tsuba from european public collections, catalogue by Haynes and Burawoy, P. 32 Nr. 56 Baur Collection 5,5 x 4,1 cm, 3,5mm The polished Shibuichi plate bears a flying crane made from silver with golden accents. The boat is made from Shakudo. The reed is made of gold an copper. The back show a silver moon behind clouds. The Tsuba comes with a custom made box. Price: 550€ + shipping. The Otsuki School The Ōtsuki (大月) school begins with Ōtsuki Korin (Mitsushige) who is a craftsman of Owari province in the early 1700s. He traced his lineage back 18 generations to Ichikawa Hirosuke who is (in legend at least) the founder of all kinko artists. Korin worked in Kyoto maintaining a shop called Senya and did metalwork of all types, including sword fittings, and followed the Goto style. Following him are Mitsutsune and Mitsuyoshi, but the 4th generation Mitsuoki would be one of the all time greats of kinko artists. In practice he is considered the founder of the school. Other great students in this school were Tokuoki, Hideoki, Minayama Oki, Tenkodo Hidekuni, Matsuo Gassan, and his son Mitsuhiro. One of them was Ikeda Takatoshi who would go on to teach the great master Kano Natsuo.6 points

-

So, as I mentioned on another thread, I recently bought the book 槍薙刀入門 (Introduction to the Yari and Naginata) - in an attempt to find a better / more authoritative reference than most of the English speaking (especially web) sources. So far: 1. The book very clearly makes no distinction between Naginata and Nagamaki etc. The latter, as often explained, is just a koshirae choice. It goes on to talk about _naka_maki (where only the central part of the tsuka is wrapped) and a few other types - but the takeaway is basically any long sword, on a long pole is a Naginata. 2. Heian to Kamakura, Naginata were considered to be powerful battlefield weapons, with nagasa up to 5 shaku, with examples of a 3 shaku blade being referred to as a ko-naginata (small naginata). 3. From the Nambokucho period, the wide body / bulging head / strong curvature style appeared, and generally became more ostentatious. By the Muromachi period, the large naginata of the previous period disappeared. 4. From the Momoyama period, sizes became more "usual" (it doesn't state exact what size this is, so I'm inferring around 2 shaku?). It also says shorter works, around 1 shaku and 2-3 bu were produced as "wives Naginata". 5. During the Edo period, Naginata became more popular among women and children of samurai families rather than samurai. It also says that Naginata were always carried as part of a wedding ceremony (in some sources, as part of a dowry). 6. Towards the end of the Edo period is considered to be a renaissance period, where Naginata from around the Nambokucho period were reproduced. All the above is subject to only coming from a single source, and may be victim to my translation abilities. If I get time later, I'll post some of the original Japanese (subject to fair-use of copyright limitations).6 points

-

6 points

-

6 points

-

Rayhans Hirotsugu story is amazing one and it highlights many things that go into submission and collecting at high level. Things that I and I suspect many others have not even thought about. I would have been perfectly happy with the sword in the original polish but more experienced eye saw how it would benefit from top class polish and the end result is most likely wonderful. I hate the business side talk about monetary values etc. but as this hobby is so connected to dealing items and various papering tiers it is unfortunate part of it. To me it just makes wonderful historical items feel bit commecialized like they are more common goods that are just traded over and over. However the talk and discussion about Jūyō items is relevant in the sense that it gives bit of "common ground" for everyone to the discussion. Of course we all have varying understanding about them. Many might have never seen one in hand, some might get to occasionally view them in hand (I admit for me even after 20+years in the hobby it is always a rare and exciting chance whenever I get to hold a Jūyō level sword in my own hands [and a fun fact they have all been wonderful swords, even though we might talk bit negatively about some Jūyō swords to a very average collector like me they are always very good quality swords]), and yes we do have collectors in the forum that are at the top level and for them these are the types of swords they are accustomed to. I think the best fact in NBTHK Jūyō is that the swords get documented to be used as a reference. Of course limited number of people will have access to the information but it is still one of the best resources towards high end items. It is also a good way to get the discussion going as people will at least have some experience of them. Trying to build up discussion about some shrine swords would prove most likely much more difficult as maybe only an handful of members would be aware of those particular swords. Still online access to Japanese dealer sites, lots of international people visiting DTI, many things like that make Jūyō swords appear to be more common than they actually are. I know I have done some calculations lately about total number of swords in Japan, as well as I should have fairly accurate guess on the number of Hozon and Tokubetsu Hozon passed items. Jūyō and Tokubetsu Jūyō you can just actually count as they are in the references. Jūyō item % is very tiny when you compare it to the number of Japanese swords in Japan. When thinking about Jūyō sessions one thing to look at is also the pass factor. I know few forum members excel in stuff like this, and have made amazing research on this. There is huge variance between the sessions in percentage of submitted items that pass. NBTHK does not hide this information at all, numbers of sent items and passed items are published in their Tōken Bijutsu magazines. Of course magazine is only sent to members, however recently NBTHK has published the results on their website too so everyone interested could have viewed them there. Like Franco and Colin wrote above it is extremely complicated with so many factors it goes way over my head. I have only fairly recently understood how important historical provenance also is. Of course it makes sense in the way that swords owned by high ranking people and families back in the day were quite often very high quality items.6 points

-

Welcome Alves. I believe your tsuba is by the Shoami school, [someone may come in with a translation of the signature] Aoi-tachi-mokko shape? Or at least tachi style. Mandarin Mansion says, Tachi-mokkō-gata (太刀木瓜形) literally means "Tachi cross shape". This style of tsuba was since ancient times mounted on tachi (太刀), large swords that were worn edge downwards, slung from a belt, mainly by cavalry. It is also known as aoi-gata (葵形) or "hollyhock shape". The style dates back to Tachi swords but continued as a formal shape fitted to Katana blades - tachi did not have the hitsu-ana [holes for kozuka and kogai] originally, though many tachi tsuba had the holes cut in later. Alves, yours is made at a time for a Katana from the design and the direction of the nakago-ana [tang hole]5 points

-

For the nakago, IF you must prevent red rust, put a drop or 2 on your fingertips, and lightly massage it onto the nakago. One or 2 drops is more than enough. Some say do nothing, but sometimes I feel the nakago can use just a little oil.5 points

-

5 points

-

You're not going to find "tanto" made in any way that isn't subject to export laws, unless maybe the blade is less than 15cm. You may find short yari that aren't subject to export process, if the blade is shorter than 15cm. If you find a flea market sword that isn't registered or is just handed over, trying to take it out the country without paperwork is a serious risk, and subject to legal action. Honestly, you're going to struggle to find a sword under $1000 from a dealer there, since most of them dump them on eBay and to the West. And those are all going to need the export process. Best bet is look for a nice kozuka, or a yari in shirasaya. Yes, you'll see many fittings in second hand shops, and some blades. And shockingly, they seem to ask double to triple the market values. Every antique dealer there seems to think that sword-related antiques are treasures. Even tsuba in flea markets are a mix of copies, and overpriced average stuff. Best bet is contact a bunch of dealers beforehand, and see if they can source something before you go.5 points

-

The Sukesada could easily be worth far more than a Nanbokucho blade, and the opposite could also easily be true. Is the Sukesada a kazuuchimono or a blade with zokumei and special order inscription? Far more information here is needed to give feedback. Both being Tokubetsu Hozon does not provide equivalency between the two swords. The Nanbokucho blade might, for example, have only been taken up to Hozon but be an exceedingly good tokuju candidate. Please share more details with us, and we can provide feedback (and the feedback you receive between a zaimei Sukesada and mumei Nanbokucho blade might also be influenced by individual preferences).5 points

-

Dear All. Apparently nothing wrong with Colin's memory, this from Christie's sale 16th/17th June 1997. Thought I had seen it but took me a minute or two to find it. Rather unhelpful catalogue description: 'A wakizashi and a rare lacquered stand of Ryujin. Mei Yamato no kami Yoshimichi, 17th century. ....with a rare lacquered wood stand of a standing Ryujin holding a tama. (Slight damage) 19th century. The stand 103cms high.' The pre sale estimate was a steep £15,000 to £20,000 though it appears not to have sold at this time. (Woops! Mistake on the estimate now corrected.) All the best,5 points

-

5 points

-

5 points

This leaderboard is set to Johannesburg/GMT+02:00