Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 09/09/2022 in all areas

-

Yes. Simple enough? May I add that this depends of course - as I explained above - on the thickness of the layers and the number of foldings. It is important to understand that ONLY homogeneous material can have predictable properties and be reliable in an application, whatever that is. The demonstration with plasticine clay is helpful to understand the effects of homogenization. Of course you have to use different colours to show the process properly. That does not mean the steel wafers are of different carbon content! As you may remember, the smith chooses his raw TAMAHAGANE first. Then he forges some of the lumps flat, cools them down quickly, and breaks them. The structure of the broken pieces (and the way they break) shows him what pieces are close in carbon content. These are then combined and fire-welded to form the initial billet.3 points

-

Dear members, Matt Jarrell is currently auctioning my Tsukamoto Kazuyuki katana for me on ebay. If there are still gendaito collectors interested in owning a premium special order Okimasa katana with a very rare alternative mei, I would recommend to visit the auction and bid for it. All the best Stefan https://www.ebay.com/itm/2251495658501 point

-

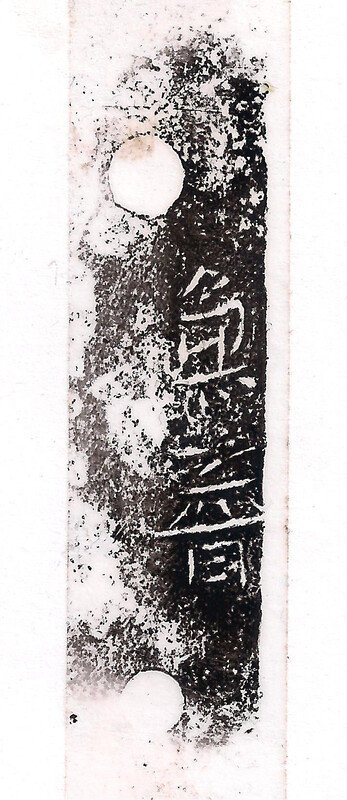

Its just recently come to my attention there is some variation in kanji of Seki swordsmith Asano Kanezane. In his mei on his swords he uses an old style of “zane” 眞. The kanji I have been using generated by my software is the modern form 真, and this "zane" can also be read as "masa". Some older published documents also use the modern form of his name, e.g. the 1944 list of Seki swordsmith registrations, and a 1952 Seki newspaper article. The modern form is also used in a 2003 table for Seki tosho that I received from Seki. However, the older form is used in a 1940 Seki city publication about swordsmiths, and the 1942 Dai Nihon Token Shoko Meikan (business directory). Unfortunately, I have used the modern form in the recent article we published in NMB on the Seki Kojima swordsmiths. Not a major error, but please be aware of it. So his name is Asano Shinichi Kanezane 浅野 新一 兼 眞1 point

-

1 point

-

(Professor) Jacques, Thank you for so generously sharing your great wealth of knowledge. If I can't read a simple paper, I clearly have nothing of value to say here, so I'll bow out and avoid further comment. I know that the word "Shihozume" is not mentioned in the study, but a similar type of lamination is shown and described. I used the word and provided an illustration for added clarity as it is a term that all here will be familiar with. Why in your (expert) opinion do those regions have differing carbon content, and why is lamination visible in the cross section if the blade is not in fact laminated? This thread has reminded me of an old acquaintance (a physicist) who wrote a simulation and a paper modelling the economy on ideal gas laws. It was a masterpiece, complete with references to papers which had no relevance to what he was using the reference to support and to (unpublished) papers he had written (which obviously only referenced other papers he had written and which had not been accepted for publication, a closed system as it were); always a lovely flourish, showing true mastery of the scientific process. His conclusions were predictably absurd. In effect he concluded that if someone wealthy were to interact with someone less well off, the wealthier party should give the other party half of their net worth - in so doing, it would naturally follow that all societal problems and political differences would resolve themselves in a matter of days (remember that this was a serious piece of academic work and was not intended as satire). He also considered (entirely arbitrarily) that this should only apply when the wealth of the wealthier party was above a certain threshold, which he was of course below. He was angry and upset that no major economics journal was interested in publishing his groundbreaking magnum opus. His more recent extra-curricular activities have involved carrying out a study on bus punctuality, which had major methodological flaws (which is quite impressive for such a simple project). I don't grasp your meaning of "bad-faith", so I suppose I'll go re-read some work by Sartre (maybe when I'm done and have thoroughly misunderstood his meaning you'll be so kind as to help me with that too). The below is from a class on Mathematics for Computer Science. It's been quite a few years since I took the class, but I like to keep a copy on hand. I think we're approaching a full-house (a rare accomplishment for a single thread), if we keep this going I'm confident we can get there! Popular Proof Techniques NOT Allowed1 point

-

1 point

-

A lot of misunderstanding of what is really going on. Let's start with the beginning: the satetsu. In the ore, the iron oxide content is 1% and it is unevenly distributed. In the tatara, temperature and pressure are also unequal what makes that in the block of tamahagane that we recover at the end, the rate of carbon can vary from 0.2% to 1.4 or 1.5%. When the smith makes tsumiwakashi, he sorts the steel according to the hada he wants to obtain; if he wants a tight hada he will assemble pieces with a fairly close carbon content (0.1% or 0.2/% difference) if he wants a looser hada, he will increase this difference. What does hammering do? The more the smith folds his steel, the more layers are numerous, thin and close to each other. The carbon rate does not vary inside the layers (C has no legs and the temperature is too low) but as the layers are closer to each other there is homogenization (also loss of carbon) but not equalization of this carbon rate, which will make the hada visible, if the carbon rate was equal everywhere the hada would be invisible. It is important to understand that what we see is the steel layer and not the weld. Take an XC75 for example and fold it as many times as you want, you will never see the folds (I had it done by a smith). To obtain an itame we choose the hammered side, to obtain a masame, we choose the non hammered side. Mark, First of all, learn to read a scientific study and the figures. Words have a meaning and it is not the one you want to see. The shihozume that you see comes from your imagination (or bad faith)1 point

-

It doesn't look like a Kanemoto. The Hamon is Togarigunome, which is a Seki style hamon. It also has a Yakidashi, which to me would place it, late 1600s.1 point

-

1 point

-

Hi Ed, small correction as your example is a Navy sword: Navy: Type 97 Kai Gunto Army: Type 98 Gunto1 point

-

Hi Chris, when you have the time can you please post photos of each sword and their mounts? We all love a good treasure find like this1 point

-

Jacques, first of all thank you for the little video which I did not see before! Concerning your question: No, there is no contradiction which I will happily explain: We have to go back a bit to explain that early Viking (6th century CE) so-called Damascus steel (correctly 'pattern-welded steel') consisted of two low-carbon iron components, one of which contained phosphorus, the other was free of it. The Viking smiths soon learned to use these materials in a way to produce predictable patterns instead of random ones in their famous sword blades. As this was non-hardenable iron, they welded a steel cutting edge onto the pattern-welded blade core. The result was a flexible blade with good cutting properties - and it looked stunning! Leaving Wootz (or Bulat) - traditional crucible or 'crystalline' high-carbon steel made in India and Persia and traded via the famous city of Damascus - aside, I would like to explain that today's pattern-welded steel as used mainly in knives is made of two or more industrial steels that have similar hardness potential. The carbon content of both alloys is very close, so each steel could be used as single material for a blade. I often use a manganese and a nickel containing steel. The blades made with this technique are very durable and visually attractive. This composite material has nothing to do with Wootz and should in fact not be called 'Damascus steel', but the market and habits stick to it. On the other side, if you combine a (potentially) hard steel (= high carbon content) with another one of low carbon content (= sub 0,3% C), there are two possible scenarios: Provided the steel layers are thick (sheet metal > 2 mm) and you only do a small number (< 3) of fire-weldings, time and temperature will not allow for a complete carbon diffusion throughout the layers. The result will be an edge that will show soft and hard spots. After some cutting work you will probably get a saw-toothed edge (depending on the pattern). If you use the same material composition but your steel sheets are thin and/or you have a considerable number of foldings and fire-weldings, carbon migration through the layers will end up in an even carbon distribution. Provided you started with 0.7% C steel for the hardenable component and the same amount of carbon-free iron, your pattern-welded steel will have 0,35% of carbon throughout the billet (not calculating the loss of material and especially carbon because of the high temperature). These are metallurgical facts, nevertheless you will read everywhere about Damascus steel beinng made of soft and hard steel, thus combining flexibility and hardness. Draw your own conlusions. Jumping back to Japanese sword blades with steel layers of hair thickness and a considerable number of foldings/weldings, you can be sure that the carbon content in a carefully forged billet is homogeneous. HEIAN and KAMAKURA era blades were made for combat, not for court presentation or decoration. The blades that survived the centuries have certainly been made with the utmost care and competence. As you may know, in a sandwich construction the outer (active) layers are most important, and so, by experience alone, the JIGANE in those old blades was made in the best possible way. I am not qualified to judge the overall quality of old Japanese sword blades, but I think that a number of aspects are involved. I think these swords were use on horseback, so this required a special SUGATA for a slicing cut.1 point

-

another variant in the overall positioning and layout of the water and the shachi.1 point

-

Jiri, Your mask is the same, except for the colour and leather lining, as one on an armour I own made by a Ki Yasukiyo in 1847. There are also minor differences in the yasuri mei but the flower on the chin and general shape are the same. Mine is inscribed 'Ki Yasukiyo' who describes himself as a pupil of 'KI Myochin Muneyasu'. What does not make sense is that the masks signed by Munyasu look nothing like mine and yours. Myochin Muneyasu was a member of the Shonai Myochin who worked for the Tsuyama Clan in Musashi. His masks have a tear-drop shaped depression at the angle of the jaw. Despite being a Tsuyama retainer, Muneyasu seems to have made armour for other families. I have also seen the same style of your and my mask signed by a Myochin Munechika and one appeared in a sale in London signed by a Munekane. Munekane turned to making tsuba later in his life but more importantly kept a diary in which he states that the maker of my mask, Yasukiyo, was really called Araji Katsuzo and that he came from Matsumoto in Nagato when he was 19 years old to study under Muneyasu. He is recorded to have stayed with Muneyasu only 3 years before returning home. In all Muneyasu / Munekane had 18 pupils between 1834 and 1844, the youngest being 13 years old, the oldest 46. Now Yasukiyo could not have been trained as an armourer in 3 years so it looks as if Muneyasu ran a kind of finishing-school that taught the latest Edo styles, and that he didn't teach himself, but left the task to Munekane who seems to hav been his assistant. I assume your Kanetsugu was yet another pupil. I have found your Kanetsugu in the diary but his age and the date when he worked with Munekane are not recorded. He has however signed the mask with his original family and personal name and does not mention that he was taught the style by the Myochin which clearly he was. Ian Bottomley1 point

-

Jean - enjoying your comments and I like the points you have made. I would posit that your example of the use of namban tetsu is not a good analogy. We were taught that the amount of namban tetsu used in the famous Yasutsugu swords (for example) was miniscule - just enough to say that he used some as it was a novelty and it added nothing to the overall product. His jigane I think most would see as quite clean and consistent so not a deliberate "damascene" hada. I think Yakumo-gitae or the Shin Ju-go-mai of Omura Kaboku would be better examples of later smiths using mixed metals for effect. Alex - the short answer to the question is "You need a full education in nihonto to appreciate why Kamakura is the best." ( I was told the same thing when I started btw) The long answer is below; Sugata - the shapes produced in this time period are considered best. Later smiths are only trying to recreate them. They may have succeeded in copying the shape but then fail at other features. Jigane - Consistancy is a big deal. Strong clean jigane expressed over the full length of the sword is most appreciated. This is true even when the jigane is larger, wilder patterend but is expressed fully throughout. Later smiths may have been successful at reproducing good jigane but then fail at other features. Hataraki - go to the glossary of any good sword book and there is a long list of features one wants to see in a sword. Read the description of celebrated Kamakura pieces and you can expect to find most of these features mentioned. Later pieces may have lots of hataraki in the ji or in the ha but are lacking in other areas. Hamon - "temperlines" are expressed in more naturalistic ways showing an artlessness that may not always be found in later works. Nakago - a well finished and perfectly aged nakago is a thing of beauty, the simple handwriting of the signature shows the artists origins as a simple craftsmen. Later signatures can be wonderful, but they reflect the education and erudition of the smith, become more like trademarks and are appreciated for different reasons. Few later smiths combine all the best features in a single work, most of the celebrated Kamakura artists consistently hit high marks in all areas in the majority of their works. This in the end is just my poor understanding of how we are to look at these works... -t1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

Item No. 256 Kozuka in copper with shakudo and gold Subject of a snake winding in and out of a hole in a rock with a toad on the reverse, signed Haruaki Hogen with kao. 19th cent. Superbly detailed piece with miniature , delicate kebori work of the toad surrounded by grasses . Signature on edge. Could this have something to do with a Sansukumi ? There are normally three characters though, and we are missing the slug. Another piece showing the skill and attention to detail that is the hallmark of Haruaki Hogen and his school.1 point

-

1 point

-

Thank you for that information Jussi, I'm always amazed by your level of commitment and grateful for your contributions. Whenever I try something like this (which is rare) I lose count or forget what I was doing. Invariably I end up writing some Python code to automate the process.0 points

This leaderboard is set to Johannesburg/GMT+02:00

.thumb.jpeg.669f6932e61c29f9609f0e532ca8ca7e.jpeg)