Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 10/08/2025 in Posts

-

They are demons, not dogs. The 'front-on' pose is classic, and these kinds of menuki are often made in identical pairs, in the same way that most tsubogasa style menuki are also made in identical pairs - its quite normal and proper. Probably late edo oni menuki, not repurposed pouch ornaments and not oversized for the application, just right for a fancy shin-shinto or Meiji look... Heres an example similar design, yours are nicer..5 points

-

.."I felt a sense of shock from which I never recovered..." Exactly—this is what I hoped to touch upon earlier. Call it bottom-up processing, a first-order experience, epiphany, shock, ... or use Scotus's definition (props to Mushin—cut to the bone ); it is a visceral experience that happens to you, a unique connection between the object and the observer, the gaze outward becomes a gaze inward ("du gleichst dem Geist den du begreifst"). If this can be learned, it likely comes closest to the concept of "Ishin-denshin", where the teacher acts more as a catalyst for the student, setting their process of self-understanding into motion (or elevating it to a new level). (Perhaps this was the role Darcy played for some forum members; at least, I got the impression that he was a good soul.) Then, it seems to me that there is at least a second, very interesting central path of top-down processing: the study of primary and secondary literature, the field of quote assemblage, hearsay, and the translators and autistic data collectors and data enthusiasts (I have the utmost respect for them). But also, and most importantly, the realm of fiction, self-worth, and the social sphere—in short, chaos. The social sphere, in my view, distinguishes the question of aesthetics (i.e., mastery) from questions about for example the essence of time or love. Aesthetics can, and often does, quickly become a socially constructed product. It can be easily manipulated and stretched. In this regard, the social dimension in the question of what is considered beautiful seems particularly relevant in a collectivist country like Japan. I would also place the following contribution here: ..."Paul relates that Albert Yamanaka held the opinion: Noda Hankei's arrogance was responsible for the blunt gracelessness of his shapes." Objective influences fade into the background, and the value of a work / a blacksmith becomes closely linked to the behavior of the social actors of the time— as well as the market, critics, curators, collectors, dealers, ... The exchange relationships between these actors play a decisive role, as they create an informal socialization around rules, trends, and the language of the market. Such network effects, especially in Japan, play a crucial role in the development of a smith’s reputation and how it is perceived in the market, an aspect I’ve so far given too little attention to, but I hope to engage in more exchange about. Specific signals, like positive evaluations by experts (the Honami family and their repeated crises of trust), protégés, peers, provenance, and familial relationships, imply a higher value. Must a sword be of higher quality just because it was owned by a famous Daimyo? The status of a smith or an artwork is negotiated through such exchange processes. This means that if a blacksmith had a great need for recognition, the ability to stage himself and his skills, and gain the support of wealthy patrons, he would enter the annals of history. But the opportunities for a blacksmith to rise, cannot be seen as entirely equal or chance-driven. In my opinion, it is 100% likely that there were blacksmiths who were nonconformists, obsessed with pioneering spirit, ahead of their time, uncompromisingly realizing their own visions and abilities, but who fell out for example of favor with wealthy contemporaries, faded into obscurity, and whose works did not gain recognition because they lacked the positive influences of provenance or similar factors. The influence of actors within the social system is determined by their status, which is, in turn, affected by their interactions with associated actors. Status, thus, becomes a self-reinforcing process. For many collectors and art buyers, interacting with the social system serves primarily to elevate their own status (how much status matters and self-worth is also frequently observed in our forum when the discussion quickly leaves the subject matter and becomes emotional). Many interesting perspectives have been outlined so far, and I look forward to learning more. I’m eager to understand more about the technical intricacies. What are the key points in Paul R. Allman’s work?4 points

-

I was thinking the original pictures were of ornaments mounted to the saya, not the tsuka. Knowing now that they are on the tsuka, I agree that these are proper menuki, not tobacco pouch ornaments. Grey4 points

-

Paul wrote a 37 page essay on the aesthetics of nihonto titled "Visions within Visions The Nature of Aesthetics and the Japanese Sword as Fine Art" for the 1976 Token Taikai Book of Lectures, and gave a lecture on the topic at that event. It may be possible to find a copy on the used book market. Paul is now retired, but was a regularly published art critic and studied nihonto with Albert Yamanaka. He proposed a range of aesthetic reactions: Catharsis Decoration Craft Low art Fine art High art He then makes the case that some nihonto does reach the level of High art. He relates his first encounter with a really good sword: "I felt a sense of shock from which I never recovered. Here was a thing of indescribable beauty that contained the idea of Kali, the creator destroyer; the ancient notion of the deadly phallus that creates; a symbol of purity; an icon of devotion; a thing of deep calm and incredible complexity that it seemed, even as I looked at it, to bring together a thousand loose ends of Man's thought and belief." In summary, High art, (which we may associate with the idea of a masterpiece) can elicit a profound emotional response. I think this aspect of the art of the sword goes beyond just being the best sword, or masterpiece, from a craft perspective (sugata, jigane, yakite), and broaches a spritual dimension. For example, Paul relates that Albert Yamanaka had the opinion: "Noda Hankei's arrogance was responsible for the blunt gracelessness of his shapes." This then enters the subjective realm of experience, sensitivity and taste, however I think there can be a consensus that some nihonto are at the High art, or masterpiece level.4 points

-

Interesting thought. I think there's a subtlety here. My 50 years of experience with craftsmanship suggests to me that when you get really good at something, as the great swordsmiths were, you've gotten there because you have always danced on the edge of loss of control... and you want to cross that edge constantly, and lose control just a little bit. If you're not doing that, you're probably not learning anymore, and it gets to be rote. The better you get, often the harder it is for others to see where you've let the process and the object take over, outside of your control, but you know. One of my professors many moons ago used to say "no threat no thrill", and I think that's pretty universal. I'd add "no threat no learning". Clearly swordsmithing is not raku... but neither is a pure industrial process, where absolute repeatability is the goal.4 points

-

3 points

-

Hi Calabrese! They wouldn't have been destroyed but probably passed on to other collectors in time. I'm sure that they were all structurally sound but the smith was trying to replicate a specific sword. Can you imagine how many attempts it must have taken to nearly duplicate this hamon? (Thus proving the point that, unless ancient swordmakers were almost mystically superior to their modern namesakes, there was never a way to totally control the distribution of martensite and the resultant hamon.)3 points

-

3 points

-

One of the local Osafuné smiths was asked to replicate the Sanchōmō a few years back. It was when Setouchi City were purchasing it for the Osafuné Sword Museum. A little birdie told me he had to create several blades at great personal expense and time, discarding all of them, before finding a possible candidate to work with. (Not strictly on topic, but somehow related)3 points

-

Steve, A friendly word of advice. The seller who removed the Yasukunito "once he found out what he had" may well have found out by watching this site and seeing your post. Either that or another visitor to the NMB may have used your photo, done an image search (very easy), found the sword and then made the seller an offer. That is what you risk every time you rush on here to post a new find before doing any research on it yourself first. You could well be shooting yourself in the foot by not hitting the books first.3 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

I will preface the following remarks with the caveat that as enthusiasts or professionals I believe we ought to do what we can to try to preserve these objects. Furthermore, I am not encouraging willy-nilly experimentation, but the deft and sympathetic hand of someone who cares. With that said... In the case of old tsuka cores and itomaki which have become so dusty and beatup as to warrent consideration for recycling, a final lease of life may be given with a few strategically and carefully placed microdots of superglue, followed by a gentle stage-by-stage cleaning of the ito and samegawa with a soft bristled toothbrush. You may be surprised at the results you can achieve with some patience. First nudging the ito around, working with what you have left to get its most appropriate position before tacking it down. Its already broken in a few places and if you want it properly functional again you would likely have to build a new core and rewrap it. Be wary that old silk can become much like a solid powder, similar to a block of ladies' foundation that can be brushed and wiped away into oblivion if one is not careful. Its fragility will depend on its age and storage conditions, but textural integrity is almost impossible to discern from photos alone. Done carefully, stage by stage without soaking it, dabbing a soft bristled toothbrush with a water and mild soap mix, rinsing then drying off each patch with absorbant paper as you go is the only way I know of, and works pretty well. Other solvents are too harsh. After removing as much of the moisture as possible with absorbant paper, to get it completely dry you can just leave it at room temp for a few days rather than any extra heating or airflow.2 points

-

I’d be tempted to leave as is. It looks like there’s already something close to a break in the ito so it’ll need a re wrap if you want to do that. Maybe save it for then and give it a clean at that point? Moisture and old thread doesn’t sound like a match made in heaven to me and I think it would be hard to keep the ito dry whilst working on the same alone and, as Sam says, you wanted an antique right?2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

I agree with you Robert. In the process of forging a sword, yakiire is the moment when everything is 'left in the lap of the gods'. This is the point at which many blades fail and are lost - even for masters. It also (metaphorically) freezes the differing sizes and specific distribution of martensite crystals in place for eternity. A master can choose the pattern and style of a hamon, down to the placement of nioi, nie or a combination of both - but he can't specify everything about the end result. Consequently, there is always an element of surprise and revelation in the tosho's first, rough polish.2 points

-

2 points

-

In order to give you a visual idea what separates a masterpiece from the better-than-average work, I'd like to show you a comparison. One blade is a masterpiece by Osafune Mitsutada made around middle of Kamakura-period. It airs a supreme yet relaxed mastery of forging and tempering in all aspects; dignity as well, if you want. The other blade is a work of Edo Ishido Tsunemitsu from Kambun-era. It is a very well made blade with brightly shining nioi-guchi, utsuri and all traits of a good choji-midare hamon. (The images were made by master-polisher Fujishiro Okisato and show the real nioi-guchi without hadori-finish) One blade I call a masterpiece; the other a very well made blade. Hope this is is helpful. reinhard2 points

-

Hello, What makes a sword a masterpiece? What are the features that are, in your view, necessary, sufficient, or ideally both, for a sword to be considered a Meito. A Meito, literally “named sword” or “famed sword” is a term used to describe masterpieces. There has long been a misconception that a Meito is a sword with a name (Go). But this is incorrect. It is because a sword is a Meito that it often comes with extraordinary provenance and in some cases, a Go (name). Let's try to go beyond Ogasawara Nobuo's famous lecture on the topic. My hope is that this question will stimulate some interesting exchanges and create educational value. Best, Hoshi1 point

-

Just what I thought so and we should expect emblem to be on this museum example.1 point

-

Marcin, A mon is a crest, kamon is family crest. We usually just say mon for short. No, the railway emblem is not what we mean when discussing mon. See here: https://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/29606-help-identity-our-mon/?do=getNewComment1 point

-

Hi All. The pictures show the hilt of a Katana I have. As you can see it is v dirty, ingrained in the ray skin, and in the binding. The common approach to this problem, is of course soap and water, plus gentle brush. This approach did NOT cross my mind. However, there must be a method to make it look more presentable. Does anybody out there know what that may be ? Has anybody successfully dealt with something similar ? Thx1 point

-

If this tsuka were mine, I’d just take a soft-bristle toothbrush and gently brush around the dusty/dirty areas. That should loosen any dirt that’s ready to come off; and then I’d leave the rest with the charming thought that “you can’t clean old” . Best of luck, -Sam1 point

-

1 point

-

I remember seeing that sword in Prague Castle 20 years ago. As I recall, it's not a mon, it's the railway symbol again in silver.1 point

-

Hokke, I will ask them, for more detail on this story. Interestingly a young and enterprising Bizen-Yaki potter near here has made a series of sword tōsōgu in fired clay, including a full-size reproduction Sanchōmō with patterns representing hamon! He told me that it took countless experiments to create one without any cracks developing during the process. (Not as expensive as using Tamahagane though!)1 point

-

Next up from my friend's collection are two iron tsuba, one a papered Shoami ji-sukashi guard, the other an ita-plate octoganally-shaped work with a signature reading "Yamashiro no kuni Fushimi no ju Kaneie." First, the ji-sukashi Shoami: This tsuba measures 7.7cm x 5.5mm, and features a variety of motif elements at the cardinal points. The condition of this piece is a bit down, with evidence of old rust pitting present, especially along the rim. As mentioned, this tsuba is papered to Shoami, with the paper dating to 2015. $145.00, plus shipping. The second tsuba is on the smaller side, measuring 6.9cm x 6.7cm x 5.5mm. This guard presents with a classical Kaneie-type landscape, highlighted here and there with bits of gold inlay. The octoganal shape is not all that commonly encountered, and this shape is emphasized further by the raised rim rising over the plate. The plate is finished it tsuchime, and presents an overall tasteful "Kyoto" feeling. The tsuba is signed "Yamashiro no kuni Fushimi no ju Kaneie," and is, I suspect, a product of the Saga or Tetsunin Kaneie atelier of the Edo Period. This piece is not to be confused with the late-Momoyama early Kaneie smiths who it is believed lived in the Fushimi area of Kyoto in the late-16th and early-17 centuries, which is why there aren't extra zeroes on the asking price here. $285.00 plus shipping. Discount for the two tsuba together: $400.00, plus shipping.1 point

-

Martin, Help me understand your question - Are you asking if presenting swords in high quality cases was a normal practice? Or are you asking if presenting swords to officials, in general, was a normal practice? I personally have not seen them in elaborate cases, but have seen them in plain wooden boxes. I have seen several presentation swords. One in our files was made by the South Manchurian Railway (Mantetsu) and presented to city officials of 3 small towns. Others are found in fancy tachi fittings and were given to railway employees when they reached 25 years of service. Looking forward to seeing the sword and box of your post.1 point

-

What you have I believe Rare, miniature Japanese samurai sword for boys' day, with a very beautiful blade, these were given to young boys in Japan on boys' day1 point

-

Thank you very much Michael! Will have a search and see about picking up a copy. If you're able to look up the smith when the book arrives, I'd very much appreciate it.1 point

-

I've recently bought the Shinto edition, but hasn't been delivered yet - if no one beats me to it, I'll happily look up your smith then. Otherwise, for your search the Japanese title is: 日本刀の研究と鑑定 (Sometimes it's for sale, but Japanese sellers transliterate it incorrectly)1 point

-

Have checked with Matsumoto Touken, who have indicated the information is from Nihonto no Kenkyu To Kantei (Shinto volume) by Tsuneishi Hideaki. Have started a thread to see about getting my hands on at least an extract but we'll see how we do!1 point

-

I do see some similarities with the form of the faces on the tsuba. I called them Foo dogs because I couldn't find another name for them. They do appear to have more of a lion like appearance than foo dog. Thank you for the great feedback and the example tsuba. Thanks, Eric1 point

-

1 point

-

Swords are held in place entirely by the wooden (bamboo) mekugi peg. The hole is usually slightly angled and the alignment slightly off so that it pulls everything together tightly when inserted. The menuki are purely decorative.1 point

-

Did I even mention the period of the sword in any of my comments? You’re the one who wrote “WW2 ERA Japanese KATANA” in the subject — not me!1 point

-

Many of the questions were asked a long time ago. And sometimes you got a very good answer. I only have a small book by Paul R. Allman "Das Bild im Bilde - Die Natur der Schönheit und das japanische Schwert als eine der feinen Künste". Translated into german in 1981. So, somewhere must be the english original. The best explanation about why a japanases sword is High Art.1 point

-

Fittings/koshirae were like clothes. They were routinely changed. When worn out, or when fashions or tastes changed. It is not deemed critical when the fittings have been replaced, as long as they antique and the quality is judged on their own merits. It's safe to say few very old swords have their original fittings.1 point

-

Go check your own forum activity. You’ve 44 pages of topics titled “WWII Japanese sword,” all just asking for comments on specific swords or translations of ones you found on eBay.. In every topic, when someone suggests something about a blade, you agree...like this particular example: "I agree with it being Muromachi Bizen era"... Why do you agree? Why does your topic say " WWII era Katana" then? Do you even know the difference? You said, “The purpose of the forum is a learning tool for everyone.” I agree — then why don’t you comment on other topics and share your knowledge so others can learn from you? You are a member in this forum for nearly 5 years..I’m sure you’ve learned something by now...or did you? I’m sorry, but one thing I can’t stand is people buying and selling something with zero knowledge and no intention to learn, while expecting others to do their dirty work for them. I find it very disrespectful. Do your own research, share your findings, and ask if you’re on the right track — that way, maybe you’ll actually learn something. And yes — either buy a membership or donate a dollar for every question you’ve asked so far...it would be the decent thing to do.1 point

-

This sword has provenance, gold inlayed nijimei "Mitsutada", has been published in at least one book; probably more, but there was only one I could find right away by searching for "Osafune Mitsutada". Its polishing has been sponsored by Japanese government, the whole process has been covered in the journal of Nara Museum of Buddhist Art. Meito? Masterpiece?1 point

-

"Japanese aesthetics though are more tricky to understand and are not just "in the eye of the beholder", which is a silly Western concept" I'm curious about this. Could you elaborate? (Jeff) A question to write a book about, but I will try: Japanese swords were not made in a vacuum. The sense for their appreciation and beauty is embedded in a culture long gone and hard to understand even for (modern) Japanese people. Even more so for us Westerners. Usually we tend to enjoy and acclaim features we can easily recognize and understand within the perimeters of our cultural background. An example for this attitude on a very high level: Etchu NORISHIGE is considered a top-swordsmith within Soshu-style of sword-making for good reasons. Western collectors are crazy about his works, for their contrast in jihada and their obvious hataraki are so spectacular. But old Japanese connaisseurs considered his work clearly inferior to MASAMUNE's and SADAMUNE's. Why? Because of its lack of dignity! "What does that suppose to mean: dignity? In 2025 we are living in a world stripped of pride and dignity! Let's make ourselves shine by all means possible." Well, samurai's aesthetics didn't work that way. My advice: Learn the difference between "aki ni sae" and just brightly shining nioi on a hamon. Furthermore study Japan's history and craftsmanship, especially paintings, sculpture, calligraphy and even everyday objects. It is a long way to go, but it is very helpful to understand appreciation of Nihon-To. reinhard1 point

-

"To my mind, it's a sword that exemplifies the best aesthetics, forging and metal for its place and period. Sometimes its also a sword that was part of breaking new ground in practice or aesthetics." (Robert S.) Well spoken and fully agreed with. But just for consideration: The criteria for excellence in metal quality and forging can be easily learned on an objective scale. Japanese aesthetics though are more tricky to understand and are not just "in the eye of the beholder", which is a silly Western concept. reinhard1 point

-

Opinion of historical figures often put down the guidelines to highlight a masterpiece. Weather it be smiths, collecters, dealers connoisseurs etc. But im a firm believer in the opinions of togishi as to what a masterpiece is. As for who else, in this world but a togi has ever had such insight into what IS or ISNT a masterpiece1 point

-

1 point

-

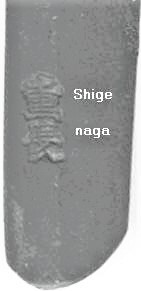

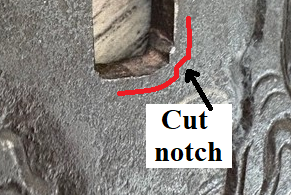

Hi Jay and welcome. I believe it is a typical Shoami school piece, they are relatively common and tend to have a waterfall and mountain scene - with minimal soft metal overlay [nunome] and some inlay. There is a notch at the bottom of the nakago-ana that suggests it has been mounted [but probably only briefly]. I am a little surprised that it is not signed, most are. [not being signed can be a "good" thing - many have fake signatures] Compare it to this one that is cast, the hitsu are rough and not filed smooth the "signature" is crude and to my eyes obviously cast-in [IMHO] Fake signature : 正阿弥包矩 (Shoami-Kanenori) Compare the cast signature to the tachi-mokko one. I strongly believe Jay's piece is hand carved, the cloud swirls on the ura are carved-in not cast. Another selling on ebay - signed and with the characteristic waterfall on one side, rocks on the opposite. Some appear "rushed" and like this one are often neglected [unsigned as well] The Tachi-mokko shaped examples are also common, each have subtle design differences, check this thread: You can also check out this auction site https://www.eldreds.com/auction-lot/iron-shin-no-maru-gata-tsuba-signed-eichizen-kin_6EB3733865 They don't know their stuff, as it is NOT signed Echizen Kinai!1 point

-

The era designations are just tools for kantei, in general swords looked like A in the Koto period and looked like B in the Shinto period. When you do Kantei there is only Koto and Shinto - if you bid on a Shinto smith for a Shinshinto maker they do not say "Wrong period". Of course we like to (need to) break it down further, most of the eras cited are political ones EG Nanbokucho and Muromachi while there are given dates for these periods swordsmiths did not change styles based on a specific date, rather they worked in the style of their teachers and perhaps followed trends seen in the capitals, only changing slowly and if you were out in the country you got the news much later. The time periods are generalizations to help you break down all the tremendous data on makers into digestible bites and think in terms of trends. A smith who was born prior to the Haitorei and who worked primarily in the Shinshinto period is a Shinto smith. Born before the Haitorei but working primarily in the modern era = Gendaito smith. There will always be smiths that overlap these dates, some who are trendsetters and some who only follow the trend later...1 point

-

1 point

-

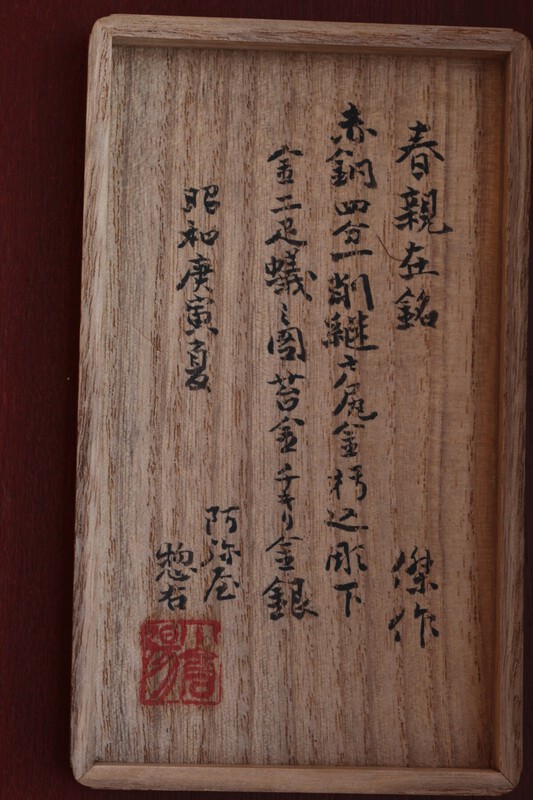

Item No. 301 Kozuka in Shakudo , Shibuichi and Gold Subject of ants on bark , signed Haruchika , 19th cent. Made in two separate sections of Shakudo and Shibuichi, joined with Gold clips and a dovetail joint, ants are inlaid onto a bark texture ground. A pleasing, unusual piece which also has an attestation by Amiya Soemon on the interior of the box lid. Can anyone help with the translation please ?1 point

This leaderboard is set to Johannesburg/GMT+02:00

.thumb.jpeg.fad864d31e1088b137cbcec3183d285c.jpeg)

.thumb.jpg.145d6d55aaa0eaa3b1744c3c1db3398a.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.87d23786c6cca2936bc5df62db352e23.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.c77ed7c940904fff9f5dc0c13ccb9e5d.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.1f15d6021ec76d2f2c2ff0ea8bb35ecc.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.189cc4ebf3eb8b19e041a94f865a11fb.jpg)