Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 09/01/2025 in all areas

-

Dear Lewis, This is a research study by Nobuo Ogasawara, conducted for and published in the Tokyo National Museum magazine in 1981. Although I made some small corrections, the translation(AI assisted) still contains some errors, but it should give you the general idea. "" The inscriptions of Shintōgo Kunimitsu, as can be seen from the rubbings presented here, each display individual differences. Broadly speaking, example 1 can be regarded as a representative inscription of the hidari-ji hokan style. Examples 2, 3, and 4 are similar to this, with example 4 bearing the latest date of Gen’ō, and is sometimes regarded as the work of a second generation. What is common among these four pieces is that the forging exhibits a well-developed ko-itame grain pattern, the ji-nie is present, and the blade shows clear ji-kage, resulting in a bright and lively jitetsu. The hamon is a straight temper line (suguha) with well-developed ko-nie, and it features pronounced kin-suji, demonstrating lively activity and excellent workmanship. In contrast, examples 5 and 6, dated to the Kagen and Tokuchi eras, show inscriptions that are finer and weaker in appearance. Despite being early in date, they convey the impression of late-period inscriptions. In terms of inscription style, they are clearly different from examples 1 through 4. Furthermore, the forging shows a pronounced masa-gokoro (straight-grain tendency), and compared to the previous four blades, the nioi-guchi of the hamon is tighter, there is less activity within the ha, and the fukura (blade curvature near the edge) tends to sink. Stylistically, examples 12 and 13 are similar, though their engraving chisels (tagane) are finer and the inscription style differs slightly. Examples 7 and 8, as well as those bearing the Buddhist posthumous name Kōshin, do not use the hidari-ji style, and example 7 also lacks the hokan (north-crown) character. These are considered a different type from examples 1 through 6, though stylistically they resemble 5 and 6. Examples 9 and 10 have overall solid inscriptions, with the third stroke of the ko in Mitsu rendered as a plain “tsu” rather than the variant “フ”. Example 9 features a midareba (irregular hamon) with pronounced kin-suji, and the forging shows a raised texture. Example 10 has an ordinary straight suguha. Example 11 differs greatly in inscription style; although it uses the hidari-ji hokan style, it shows unique characteristics not shared with the others. If anything, opinions have shifted toward a broader view that the pieces in question may date from after the inscription bearing the Buddhist posthumous name Kōshin in Shōwa 4. In that case, the works of Bunpō, Gen’ō, and Genkō would be considered second-generation. However, when it comes to pieces with only the two-character inscription, such as the famous Aizu Shintōgo Kunimitsu, it becomes difficult to determine whether they belong to the first or second generation. A detailed examination of Shintō Gokunikimitsu inscriptions shows that each character varies slightly, making it virtually impossible to estimate the production date based solely on a two-character inscription. Nonetheless, in addition to the common inscription style featuring the “left-character” with a north-crown (hidari-ji hokkan), there are several distinct variants: 1. Those executed with a fine chisel (hoso-zan), where the inscription appears somewhat larger (though in reality almost the same). Examples include works dated to Kagen 4 and Tokuchi 3 (Important Cultural Properties), and, although tachi, the famous Mutsu Shintōgo is included in this group. 2. Those not using the left-character north-crown, such as pieces in the Tokyo National Museum or those bearing the Buddhist posthumous name Kōshin. 3. Those where the “kuni” character is a left-character but the “mitsu” character does not have a north-crown, or where the third stroke of “mitsu” is unusually firm, as seen in the famous Ran Shintōgo. 4. Those with large inscriptions and a firm, rigid style, such as the famous Kojiri Gokunimitsu and the tachi passed down from the Tokugawa family. The four types described above differ from the typical left-character north-crown (hidari-ji hokkan) inscriptions. Based on these differences, it can reasonably be concluded that the inscriptions were not cut by a single hand. Rather than strictly distinguishing first and second generations, it is more plausible to view the head smith Kunimitsu as a single master while Shintō Kunimitsu operated as a collective workshop consisting of multiple smiths. Naturally, certain stages of sword-making required a lead smith, and there may have been several lead smiths working simultaneously, making the finished products the result of collaborative effort. On a larger scale, tasks such as forging, finishing, hardening, and polishing were likely divided among specialists. Although it is difficult to determine the precise scale of the Shintogo Kunimitsu workshop in Kamakura, it is reasonable to assume that multiple smiths inscribed the Kunimitsu signature during the lifetime of the head master. ""6 points

-

Hi Martin, the would indicate that it is by or purports to be by the famous Shinto Settsu smith Omi (no) kami Sukenao: 近江守高木 (住助直) Omi (no) kami Takagi (missing portion: ju Sukenao) It is dated Enpo 6 (the year 1678). https://nihontoclub.com/smiths/SUK3584 points

-

Here are two works from my collection by Zen masters of two different sects, brushed several centuries apart. It is a testament to the direct transmission of the Zen mind from master to disciple through the generations that preserves the powerful expression of Buddha-nature in the practice of calligraphy. Tetsugyu (1628-1700). Chinese Obaku sect Zen master who studied with Teishu, Ryukei, Ingen, Mokuan, and Sokuhi. The last three were leading Zen masters who were also noted calligraphers of his time. The two characters of this bold and dynamic calligraphy in cursive script can mean 'solitary dew,' but they are part of the Zen phrase 'Self revealed among the myriad of things,' representing the state of enlightenment. According to Buddhist belief, the life of an individual is no more than a solitary drop of dew, but within this impermanence exists the inherent Buddha-nature, which needs only to be awakened and brought forth. Yamaoka Tesshu (山岡 鉄舟), 1836-1888. This is his version of "Self Revealed" brushed two centuries after Tetsugyu with an idiosyncratic albeit consistent zukushi-ji style.3 points

-

Examples below. https://www.google.com/search?sca_esv=85427b9423f451d4&rlz=1C1ONGR_enUS1136US1136&sxsrf=AE3TifNl6HyAhyPtSRMRy6sEIuzysY2-9w:1756742766322&udm=2&fbs=AIIjpHxU7SXXniUZfeShr2fp4giZ1Y6MJ25_tmWITc7uy4KIeuYzzFkfneXafNx6OMdA4MRo3L_oOc-1oJ7O1RV73dx3MIyCigtuiU2aDjExIvydX85cOq96-7Mxd4KSNCLhHwZjNl1D--59A3Pz1jRAtenzCJ-qzCnOKtvU69k0YYAuhlzxHSrRNQ-gtEYBj8xSow3FJ3v7l7zsi4eO0Nw9mEGcGVLxNQ&q=近江守高木住助直&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiHqbHk-LePAxWBSDABHaKYAO8QtKgLegQIFRAB&biw=1536&bih=791&dpr=1.253 points

-

宇和島 is spelled Uwajima today in English, but it does sound like 'Uwadjima'. This branch of the Date clan was started by Date Masamune's eldest son, Hidemune. Because he was born by a consort, and not by Masamune's proper designated wife, he could not inherit Sendai, so he was sent to be first Lord of Uwajima in Shikoku. He had been brought up in the way of the Samurai, learning both literature and martial arts, 文武両道 Bunbu Ryodo.3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

It is not unusual for Kyu-Gunto to be fitted with older blades using this method, by threading the back part of the nakago. A known method. Looks like a nice blade, well signed.2 points

-

No, we are all on different pages. 十九 is 19, 1944. 十六 is 16, 1941 十八 is 18, 1943 It is possible that the hat issue type stayed the same but the last number was altered depending on which year each hat was actually issued. If this is the case, to me the last/latest number (Showa 19) is most likely, regardless of the covered number(s).2 points

-

Hi Florian, You make some good points here, especially about the Hoan smiths making their works for the Asano family (and perhaps for other high-ranking clans), but not for the masses. For some of the most highly regarded tsubako (e.g. Hoan, Nobuiye, Yamakichibei, and the Higo smiths), they were indeed retained by Buke families, and did not, as far as I know, make their works availably broadly and generally to the public in common commerce. I believe this was true of the Akao as well. As retained craftsmen, they received a stipend, thus removing the need (and, perhaps, the permission) to sell their tsuba to the masses. As for the 10-koku stipend the Shodai was provided by the Asano, while some may see this amount as meager, it may not actually be so. We may need more information about the particular circumstances involved, but if my understanding is correct, 1 koku of rice = the amount of rice required to feed one person for a year. The Shodai Hoan did not operate a "school," per se, with several students working in an atelier; rather, he had a son-in-law who became the Nidai Hoan, perhaps/probably not until the passing of the Shodai in 1613/1614. It is possible, if not probable, therefore, that the Shodai worked alone as a tsubako, with no actual "school" during his lifetime. So, 10 koku of rice, in being enough to feed ten people for a year, may have been more than adequate for the Shodai and his family.2 points

-

2 points

-

1 point

-

Nice little after show presentation in case anyone is thinking of attending next year June 12-14, 2026. Highly recommended. https://youtube.com/shorts/DrrY8G1-4T4?si=U3V_2lzIJNAU-9FG1 point

-

1 point

-

Oh, I see, to be honest as much as I love kyu-Guntos I havent seen any with older blades disassembled.1 point

-

Last one for today... This is a little jewel of a tsuba, a tanto-sized piece done in what I believe is shibuich, with shakudo(?) and gold-leaf highlighting of the plovers flying about above the raging waves. The carving of the motif on this tsuba is sophisticated and very pleasing, with the plovers done in a high-relief, while the waves are rendered in a fluid and lively kebori. The tsuba measures 5.6 cm x 4.8 cm x 3 mm. It is kawari- gata (or kobushi-gata) in shape, with a rim-edge that curls up over the plate in various places around the tsuba. Seppa-zuri is clearly evident. A charming little sword guard. $275.00, plus shipping.1 point

-

I enjoyed reading that treatise Okan. Certainly provides more food for thought and some hypotheses regarding the organization of the Kunimitsu atelier. I thought what was especially interesting was the use of a thin chisel between 1306 and 1308, and the differences in forging style with pronounced masa-gokoro during this period. It will be interesting to see if this forge welding pattern is present in my 1308 tanto after polish. Another useful datapoint is that the Buddhist koshin inscription was posthumous. Given this fact, did Shintogo Kunimitsu die in 1310 or earlier (the 2nd character for the tachi nengo is a little unclear)? I like the idea of a collaborative/cooperative working environment. This would fit many of the theories that connect the different smiths, both directly as apprentices and possibly later as a partnership with 2+, more or less independent groups, working in the same atelier. Headed by the master Shintogo Kunimitsu with his own apprentices, Kunihiro, Kunishige, Norishige and Kuniyasu (Daishinbo), whilst on the other side there's Yukimitsu and his son by birth or adoption, Masamune.1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

I think you are correct - from the dates it must have been a very speedy "repair" - it will be interesting to see if they make a profit from the work!1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

For me, there are two ways of looking at this. Either a link to history, a real link, but that isn't happening 99.9% of the time and is unrealistic for many. Or You accept such a medley as above, for display. I have one now, nothing matches at all apart from the Brown ito, sageo and the fact im content with what i spent and how they look. Its not as though the ghosts of the past will haunt me over it, as they did the same. Will point out, no theme on fittings, plain and simple. all fitted out late Edo. (apart from sageo lol) Would rather have something i like and put together for display, rather than another cobbled together overpriced concoction that someone writes "daisho". Own personal opinion is a lot you see was put together in the early 1900s. and beyond, no way of knowing without provenance/proof. Have to say, Brown ito is my favourite, maybe that comes from Shogun. (original)1 point

-

1 point

-

The inscription on the flag above the Mon reads “八幡大菩薩” (Hachiman Dai Bosatsu)… The caption on the right refers to a certain 相馬師常 (Souma Shitsune) who “obviously” received this flag from 源 頼朝 (Minamoto no Yoritomo)….if I got it right?!1 point

-

Got discharged today. They did some stuff, but some stuff they were reluctant to do because of the blood thinners and need to close some veins. So we are waiting it out to see if I decide to dump huge amounts of blood again. Sunday was scary...almost passed out and couldn't move my arms while I was showering to take myself to hospital. Ended up calling an ambulance. First time. Anyways, all ok for now, we'll see what happens. There are no indicators of anything specific causing it or anything very concerning. G&C scopes are clear...still dealing with the same abscess/fistula thing from the beginning of the year.1 point

-

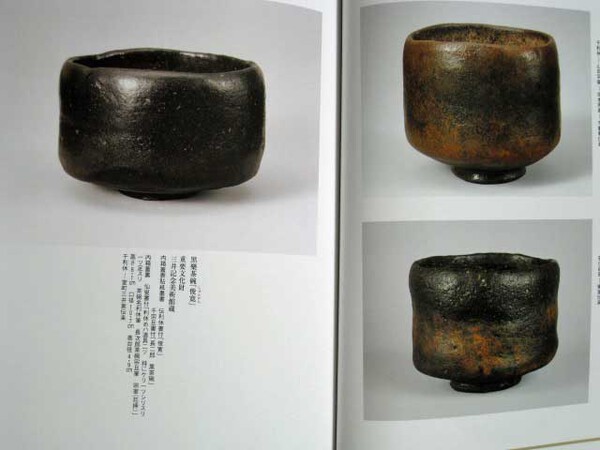

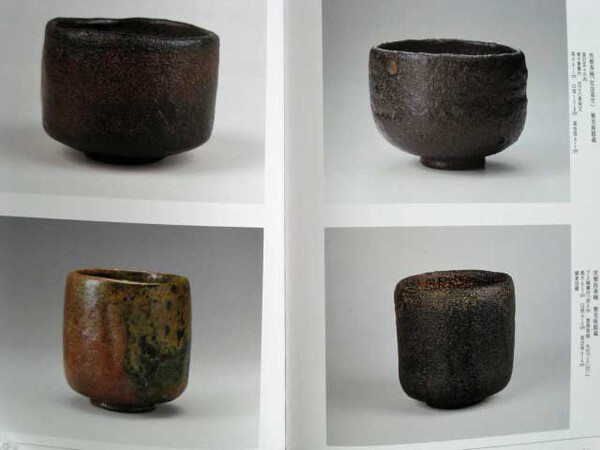

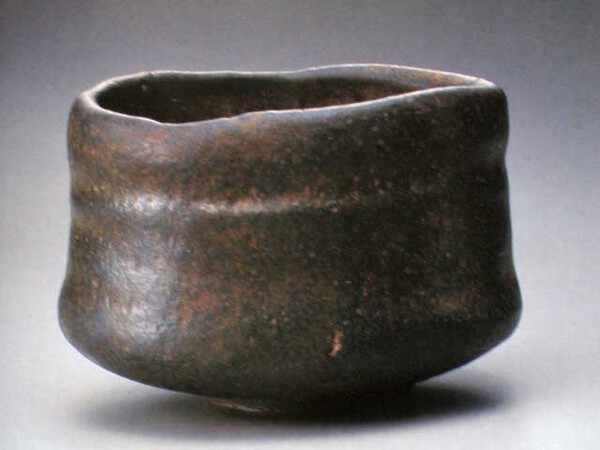

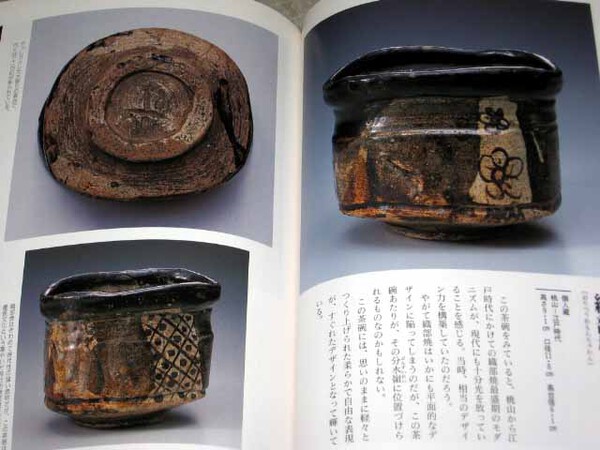

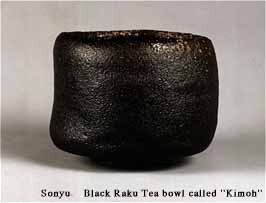

Here are some examples of important masterwork tea wares that show similarities to YKB and other Momoyama - Early Edo period tsubako such as Nobuie and Hoan. It is thought the pottery came first, and was developed as a unique aesthetic style that complemented and reinforced the intense experience of the Soan, Wabi, and Daimyo forms of cha-no-yu. The practice of cha-no-yu went 'viral', as we say today, in the Momoyama period, and was embraced by all classes of Japanese. Read about the great Kitano tea gathering for example. Because Buddhism was of vital interest to both the Tea Master and the Warrior, it is not surprising that the unique visual language developed for cha-no-yu crossed over into tsuba.1 point

-

Important to remember that in many cases, older literature (or brand new, for that matter) will contain and repeat errors, faulty and/or incomplete information, and questionable assumptions, premises, beliefs, reasoning, and conclusions. In order properly to pursue an analysis and assessment of a subject like this, it is crucial both to examine many examples of the tsuba in hand, as well as to educate oneself on larger historical and cultural contexts informing the creating of these pieces. Sharp skepticism is critical in this endeavor. Below are a few more photos of Yamakichibei guards. These include both "Meijin Shodai" (the last two examples) and Nidai pieces. Cheers, Steve1 point

This leaderboard is set to Johannesburg/GMT+02:00

(1).thumb.jpg.1671a6451e9174ebde07db8c62899aac.jpg)

(1).thumb.jpg.c1476d737b592707e2c484a9f8b7dfaa.jpg)