Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 11/20/2025 in Posts

-

3 points

-

Noshu Seki ju Kanekami saku. I would look into the late Muromachi Sue-Seki group. Best regards, Ray3 points

-

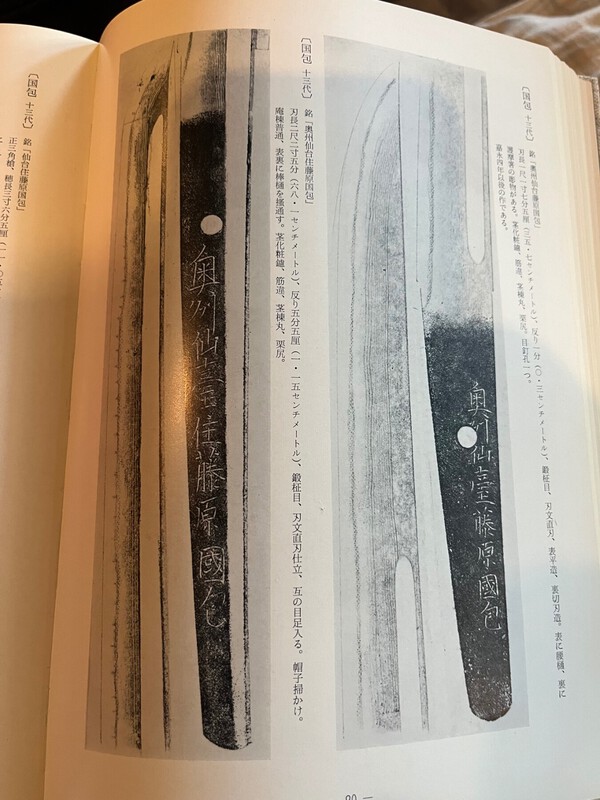

For sale is 1 copy + English translation. Advantage is it's already in the EU, so no additional customs. Limited Ed to 500 + signed by author. The book features high-resolution photographs of Nobuie tsuba, enabling readers to observe appraisal points, stylistic changes, and variations in signature across different periods.The quality is sufficient to examine iron textures, chisel marks, and forms from the mimi to the seppadai. This makes the volume not only a treasure for enthusiasts, but also an invaluable academic resource for researchers. Building upon Ito Mitsuru’s decades of scholarship, the book presents both well-known and newly identified Nobuie works in a clear, structured way. Set against the dynamic cultural background of the late Momoyama and early Edo periods, it explains the characteristics of the hanare-mei and futoji-mei works, traces how these signatures evolved, and explores the aesthetics behind them—offering a fresh perspective on Nobuie studies. A complete English translation and commentary on Nobuie — in softcover. This comprehensive edition includes every hanare-mei and futoji-mei Nobuie description, along with a substantially expanded commentary and glossary. Price 330€ + shipping2 points

-

I have this book: HIGHLY recommended for anyone with an interest in the Nobuie smiths and the context out of which they arose. This is a lavishly done publication, highly readable, with beautiful black and while life-size images of the pieces illustrated. We desperately need more scholarship on this level in our field. Superb.2 points

-

Hi Logan, Unless it’s being offered at a pretty low price, I’d recommend continuing to shop around. It does look like a genuine wakizashi, but in its current condition, it’ll be extremely difficult to appreciate any activities in the steel. The hamon is very hard to make out in the photos; I suspect due to a buffing or improper polish; and the nearly nonexistent hamachi suggests a tired blade. Overall, I think you could find something more enjoyable if you wait for the right piece. Other opinions may vary, but that's what I see. All the best, -Sam2 points

-

The theme that I have attached above, in my opinion, gives an idea of what and how it was done. To be specific, it's a fake, a copy! At least because this product has nothing to do with the Soten school and its followers, the manual work here is minimal, as a rule, only fine-tuning and refinement. The exact date and place of production will not change its essence in any way, because the production process itself and the quality are distinguishable from manual labor. Just a cast coloring…2 points

-

I can’t say for certain, but it would seem unlikely. The second one up from the bottom has the little flat area for the kozuka, which would imply an attention to detail that might be a step too far. I would guess that towards the end of the Edo period there would be so many of these things floating around that there would be no need to make new ones for something like this. It fits with the repurposing of menuki into earrings, and pouch clasps, and the re-use of tsuba in furniture and boxes that we also see.2 points

-

There are about 40 Jūyō Gō and about half of those are den Gō. Of those, six are old daimyō possessions, two are meitō, two have Hon’ami Kōjō attributions. To this we should add the seven Jubun examples which are all denrai and mostly meibutsu. So as far as the gold standards we are indeed in rarified air here. There are blades that passed Jūyō as Taima (recall that Taima can be very close to Yukimitsu) and Sanekage that were reattributed to Gō at Tokuju. I also wouldn’t say that Gō was a “reproducer” of Masamune’s work. The original Sōshū group working in Shintōgo’s forge in Kamakura were Yukimitsu, Norishige, and Masamune, likely in that order of seniority. It seems like other smiths likely came and went as the school matured, and Gō has often been associated with Norishige as they were both from Etchu province. My mental model is more like a mixing pot of traditions and ideas than a strictly hierarchical structure, at least in the first generation. We do see significant change in working styles in these smiths. Early Yukimitsu looks like Shintōgo, and turns into something more flamboyant. Norishige’s iconic matsukawa-hada develops slowly over his career. So I think perhaps Gō was following his own path, heavily influenced by the senior smiths around him of course. His work often has a little Yamato “seasoning” I think. There are blades that are attributed to Gō that have a distinct feeling of ideas from Yukimitsu, and especially Norishige and Masamune… but overall his work is characterized by being somewhat calmer in the chikei and kinsuji, but the jiba is always bright. The deki has incredible clarity. Despite the ichimai boshi being a kantei point, most Gō works do not have it. Certainly distinguishing between the top rank of Sōshū work can be difficult, but it can be accomplished…. Hope that helps.2 points

-

Hi Kevin, Great question. There is a tradition of attribution that goes back to the 17th century where respected appraisers wrote the name of the maker in gold inlay on the tang of the blade (Kinzogan). Some of the shortening were performed by this group, called the Hon'ami, and as a result they had access to many more signatures than we do today. The attribution "Go Yoshihiro" has a number of canonical traits (e.g., Ichimai boshi, first class nie, shallow sori, habuchi that increases towards the kissaki...) that have been studied since the Momoyama period. There is, of course, a substantial degree of uncertainty with attributed blades. Attributions on mumei works are best understood as "this is the most likely maker given what we know today" - and even more conservatively as a way to state that a sword expresses certain traits and a certain level of quality that is in line with reputation of a certain master smith. In this sense, there is a tradition of attribution that has been honed over generation of competent judges, based on ancient literature and oral transmission. I would advise caution on mumei Soshu blades to big names that are without Ko-Kiwame (old appraisal by the reputable judges) or established provenance from Daimyo collection with a high-level record of gift-giving. Makers during the Shinto era, such as Nanki Shigekuni or Shinkai came very close to Go, and one should always examine the sword critically. Best, Hoshi2 points

-

Hi, all, i just fell in love for this sword (https://eirakudo.shop/333326 )it happens to me 2 or 3 times a month ... so i believe I'm a compulsive "in love" or I spend to mutch time watching swords pictures. I think it is beautiful, but I read on this forum, the pictures from this shop is very nice and enhance the beauty of the blades ... The information a found for this sword (I could be completely wrong) -it was forged by the 2 generation Izumi no kami Kinmichi at the end of his life and signed by his son Iga no kami Kinmichi. I believe it was the last sword of Izumi -It was forged the 13 august the 14th year genroku. (1701) I'm very curious about your thought about this sword... can you give me any advices about this shop ? thanks !1 point

-

1 point

-

Please see below for Ogawa Kanekuni. https://www.google.com/search?q="ogawa+kanekuni"+site%3Amilitaria.co.za&sca_esv=18637f1ce6371d1f&rlz=1C1YTUH_enUS1164US1164&sxsrf=AE3TifOV34tbjjQ9yRuvGop5ne4Ec7zGcg%3A1763671772968&ei=3H4faergOsybwbkPwdKH2A4&ved=0ahUKEwjqvpyszYGRAxXMTTABHUHpAesQ4dUDCBE&uact=5&oq="ogawa+kanekuni"+site%3Amilitaria.co.za&gs_lp=Egxnd3Mtd2l6LXNlcnAiJSJvZ2F3YSBrYW5la3VuaSIgc2l0ZTptaWxpdGFyaWEuY28uemFI1BFQ1QFYkA9wAXgAkAEAmAGMAaABuQWqAQMzLjS4AQPIAQD4AQH4AQKYAgegApYFwgIHEAAYsAMYHsICCxAAGIAEGLADGKIEwgIIEAAYsAMY7wXCAgYQABgWGB7CAggQABiABBiiBMICBRAAGO8FwgIFECEYoAHCAgUQIRirApgDAIgGAZAGBZIHAzIuNaAH2A6yBwMxLjW4B5EFwgcFMy4yLjLIBw8&sclient=gws-wiz-serp1 point

-

The smith is Murayama Kanetoshi and it’s dated a lucky day in February 1939. Do you have better pictures of the nakago? The pictures cut off part of the Mei and the other characters on the date side are not well-focused.1 point

-

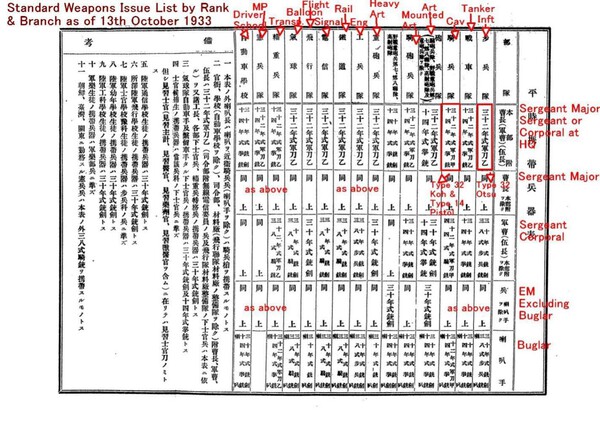

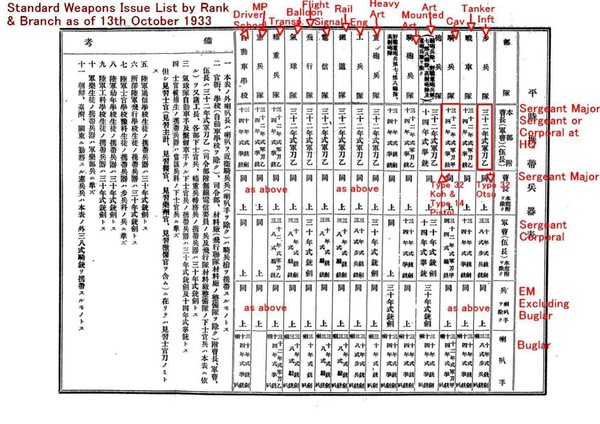

The document and the red notes are from Nick Komyia when he was still alive. He had a detailed report on the development of Japanese equipment, etc. But he only briefly mentioned the most important aspect. Namely, the way equipment and armament were carried. (For example, some units carried the bread bag on the opposite side, as did the field flask.) I am interested in the Taisho era; unfortunately, this document is the only one that is generally applicable to that time, but it says nothing, for example, about the use of backpacks (e.g., artillery only until 1924) and personnel of the light machine gun appeared in parades at the time without weapons, only with ammunition. Everything is very complicated...1 point

-

Chris: Just as an aside, the term nyudo is used on swords to describe a monk or one who has joined the priesthood. John C.1 point

-

In my opinion the tang was most likely signed as, Bishū Osafune (Insert smith here) 備州長船□□. It does not feature the common Gorōzaemon signature, 備前国住長船五郎左衛門尉清光.1 point

-

1 point

-

Looks good for me. Carefully polished.1 point

-

1 point

-

前伯州信高入道 – Zen (former) Hakushu Nobutaka nyudo I believe that this Nobutaka is the 2nd generation. Ref. Nobutaka - NOB488 | Nihonto Club1 point

-

@fox1 Sam your blade is early war with a SHO stamp in sakura flower, which indlicates not fully traditionally made. But looks a good item. Of note it is in "samurai" civilian mounts not Army gunto. YOSHINAO 義尚: real name Takeyama Tsutomu (武山勲) Born Meiji 39 (1906) August 17, older brother of Yoshitomi (義臣). Registered as a Seki smith in Showa 14 (1939) October 27 (age 33). Rikugun-jumei-tōshō. Died Showa 57 (1982) July 11. In Akihide 1942 ranking is Jōkō no retsu (5/7). In exhibition 6th Shinsakuto 1941 is second seat (2/5). Examples of mei: (“Seki Fujiwara Yoshinao”) (“Noshu Seki Takeyama Yoshinao saku” SHO), (“Seki Fujiwara Yoshinao saku” SHO), (“Seki Fujiwara Yoshinao saku kore”) (“Noshu ju Takeyama Yoshinao kin saku”) (“Noshu Seki ju nin Takeyama Yoshinao kin saku” SEKI).1 point

-

Here is a google translation for the regs on the left side: Translation 1. The long sword, trumpet, and cavalry equipment (excluding the sabretache) are to be carried by the cavalry. 2. Officers at government offices, schools (excluding the self-funded car school), headquarters, material depots (excluding air corps material depots and maintenance units), military police, and corporals are to carry the Type 32 Model B sword (non-commissioned officers and soldiers of the headquarters non-commissioned officer committee and air corps maintenance units are excluded from this table). 3. Chief mechanics, non-commissioned officers and soldiers of all units, and heavy artillery special duty personnel are to carry the Type 30 bayonet. 4. Non-commissioned officers and soldiers of the balloon corps are to carry the Type 30 and Type 14 weapons. 5. Students of the Army Signal School are to carry the Type 30 bayonet. 6. Students of the Army Aviation School are to carry the Type 30 bayonet. 7. Students of the Army Cadet School are to carry the branch insignia of their assigned branch. (Including acting paymasters, acting medical officers, acting veterinary officers, and acting engineering officers) Acting officers are to carry the officer's sword. 8. Students of the Army Youth School are to carry the Type 30 bayonet. 9. Students of the Army Engineering School are to carry the Type 30 bayonet. 10. Students of the Military Music School are to carry the Type 30 bayonet. 11. The Type 38 cavalry rifle is to be carried in addition to this table by the Chief of Military Police in Kyoto, Osaka, Kobe, and the high-ranking military police chiefs. John C.1 point

-

https://www.skinnerinc.com/auctions/3046T/lots/1058 Those these are all of the same general pattern, they are not identical and all show small variations. Like many of this type the tagane-ato punch marks around the nakago-ana were probably added in the workshop when manufactured, to give the impression that they had been mounted but are usually just cosmetic - some would have later been mounted but not many. https://auctions.yahoo.co.jp/jp/auction/g1197874839 https://www.jauce.com/auction/g1197874839 Auction still running. Another type that depicts the same scene are usually described as Hamano - the Hamano ones are identical and must have been mass produced but are often not finished to the same standards. I would much rather the hand finished Soten signed type! These can be expenive rubbish.1 point

-

Hello, yes this is an arsenal blade made during WW2. The inscription is 関武山義尚作 Seki Takeyama Yoshinao saku which means "Takeyama Yoshinao of Seki (city) made this".1 point

-

Everything has already been said correctly here. It's from the same series, I think: Sometimes they were even cast, and then they were finished manually. It usually has no value, they were made in large numbers with minimal labor costs. An imitation of the Soten school, but in this case the signature does not play any role.1 point

-

1 point

-

Given how precisely all of those fuchi match in size and shape, I rather wonder if they weren't all made as a set, for this very purpose. Totally gorgeous object!1 point

-

Not unusual here in the States, probably to keep the kids away from them. I have heard of rifles and swords being found in walls. One such example was a Type 44 Carbine with the folding bayonet cut off. Another common occurrence was to throw them out in the trash. Back in the 1950s, my father saved a Japanese rifle that was sticking out of the trash can. He asked the housewife who answered the door if he could have it and she said go ahead. She told him it was missing the bolt though.1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

Thank you everyone for such great insight on the topic. I have very little knowledge of Shoshu so every bit of information is greatly appreciated 🙏🙏🙏1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

That's reasonably common. "Classic" Go has not many options except go down to Tametsugu and the upgrade is probably Masamune. For Shizu it does not have togari, there is slight chance to go Sadamune, you can't go Yukimitsu because hamon is too uneven, Hasebe would typically be rather different jigane. I do dislike dealers. They always write as if they've been family friends with most of the smiths, forcing them to keep in mind when Go's birthday is, and what did Masamune give him the last time everyone been drinking together. That rascal. They don't write "the earliest mentioning of Go is in X", "his birthday is first mentioned in Y". Go, Sadamune, Yukimitsu and Norishige do have arch-typical different clusters; as a pure personal guess in terms of width of the hamon, which continuously increases with time in Soshu until hitatsura and Hasebe, Go is beyond Yukimitsu and at least in Sadamune's timeframe, but before Hasebe. His works are unusually compact timewise, but this might be relative because many others are unusually wide - Tametsugu, Yukimitsu, even Norishige. Then again, nobody in Soshu was satisfied doing just the arch-typical, there are also many works that don't stick anywhere in particular and the early texts that everyone cites with respect to Masamune, somehow dismissing the fact they provide many names which disappeared from our mind because there are no signed examples... well, its not like there are many in Soshu overall.1 point

-

I can only see gilding, not inlay. However, the feathers on the belly look like shakudo inlay. Is it possible to take clearer photos from different angles? Here is a good example of gold inlaying on the spots on the body. At first glance, it seems simple, but it is actually quite elegant. However, I can see that the eyes are covered with gold, especially on the second pair.1 point

-

To me it looks more like Koshi Sori (Bizen Sori)1 point

-

First time post, uploaded photograph incorrectly first time, had to redo. Did not mean any disrespect. I am certainly appreciative of the replies received! Thanks again, Willy1 point

-

You are all good Willy; and no problem at all! These forums can take some getting used to - and our members sometimes forget the early days. It appears you're in my neck-of-the-woods, I'm hosting a Nihonto club meeting on Sunday December 7th, in Tualatin Oregon. If you'd like information about address/time, send me a message . All the best and welcome to the forum! -Sam1 point

-

As an addendum, this is regarded as a Koto blade for all you aficionados out there! (Or if you are new to nihonto and looking for something that fits the description).1 point

-

Yep, some good points. I personally do not intend on getting rid of the sword regardless of the outcome as it's a beautiful piece that speaks to me. I bought it TH and the submission is more about the sword itself trying to discern the delta of Enju -> Yoshimasa and the fact that I have never held an Enju piece (and I have held a few) that has striking moist jigane (strong uruoi) like this. Also, I might still submit the original blade in the thread. In February I will be in Japan to inspect the final polish and my contacts over there have already suggested I submit it. For what it is worth, I showed this (Enju/Yoshimasa) sword to Bob Benson and his son Nicholas in Hawaii in much higher detail than posted here and they have asked me to send it to them in March and said - and I quote - "It is a good candidate for Juyo". They also suggested I send it to Tanobe for some thoughts on the conflicting attribution while it's there. All that being said, I appreciate all of the inputs and this is all part of the fun to me. I love good swords, at all levels1 point

-

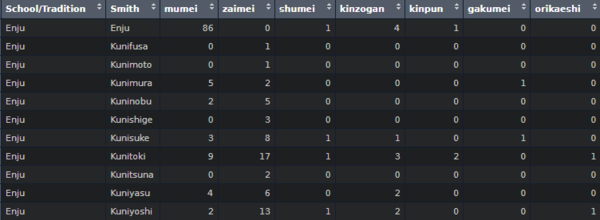

A fun little exercise I did using @Jussi Ekholm's wonderful data he's provided to the forum. The filter here is just looking at Juyo blades (Not TJ or above, but I could add that in easily enough), and the first numeric column is the number of Mumei blades and the 2nd numeric column are non_mumei. In the case of the Enju/Enju combo this includes 5 instances where there is a shumei, kinpun mei, or kinzogan mei simply to Enju. The columns in order are: School/Tradition, Smith, # mumei, # non_mumei. Enju Enju 86 5 Enju Kunifusa 0 1 Enju Kunimoto 0 1 Enju Kunimura 5 3 Enju Kuninobu 2 5 Enju Kunishige 0 3 Enju Kunisuke 3 11 Enju Kunitoki 9 23 Enju Kunitsuna 0 2 Enju Kuniyasu 4 8 Enju Kuniyoshi 2 17 There are still some fringe cases that I'm working out the bugs with where the count may be off 1 or 2, but this was a quick bit of tinkering. Edit: I did more tinkering and here's a big table with most of the possibilities of mei realized: Again, a huge shout out to Jussi for the compilation work he's done. I can't possibly say enough about how insightful it has been for me as a data nerd to pour over different possibilities and arrangements of the data he's collected and given to members of this forum. Its truly invaluable and selfless of him for giving this to the NMB community!1 point

-

Markus Sesko wrote an excellent summary of samurai incomes and sword prices (https://nihonto.com/samurai-income/), which identified how high sword prices from known swordsmiths were, relative to samurai real incomes ( net of enforced borrowing by Daimyos, retainer costs, etc.). He quotes prices of 5 - 7 ryo and up for new swords, which could, depending on the income level of the samurai, be multiple years of potentially available income. And that is only "potentially" available income, because many samurai, even those with incomes above the lowest level, were chronically going into debt. I have recently been doing a lot of research into samurai economics and culture during the Edo period, and came across another reference to prices of used swords in "Tour of Duty", a fascinating book by Constantine Nomikos Vaporis on the impact of the alternate attendance system. He provides actual ledgers from various samurai of both their regular expenses, as well as of purchases during their period in Edo. A samurai named Mori Masana, who clearly had more money than most, although the source of his money is unclear, bought three swords during his Edo tour in 1828-29 (as well as something like 20 tsuba!). In his ledger he noted priced for two of the swords: 1 ryo 2 shu, and 1 ryo 1 bu. Of the latter sword he notes that it is "a fine sword that I can wear with pride", which given that he was clearly higher up in the ranks of samurai, certainly means that it wasn't a used low level "off the peg" sword, although unfortunately he doesn't give any further details. While this is a very limited sample, it does indicate that even pretty decent used swords were available for a price much lower than a new sword - in a sense, (and obviously with the exception of masterpieces) it sounds like they depreciated with age - probably because they were somewhat "out of style", or didn't provide the boasting power of "look at the sword I had made"! Robert S1 point

-

Because I'm researching these issues, I got a copy of a book that Markus Sesko mentioned "A Study of Samurai Income and Entrepeneurship" by Kozo Yamamura. (As an aside, a copy of the book popped up in small town bookstore in British Columbia! I'd love to know why :-) ) A good example of the data in the book is a table on the distribution of incomes in Okayama han in 1673, 1700, and 1840 to 44. For 1700: In the year 1700 stipend in koku Number of retainers Total cost 10000+ 6 60,000 5-10,000 3 22,500 1 - 5,000 25 75,000 500 - 1,000 36 27,000 400 - 500 22 9,900 300 - 400 81 28,350 200 - 300 159 39,750 150 - 200 101 17,675 100 - 150 54 6,750 50 - 100 217 16,275 30 - 50 427 17,080 20 - 30 1126 28,150 10 - 20 270 4,050 < 10 93 837 Total 2620 353,317 Median income, koku 20 - 30 Mean income 135 This table includes both retainers paid in koku, and in hyo. The book gives some context about this data: Many of the lower level retainers were in fact paid by higher level retainers, not the han. Thus this han (with a value of 350,000 koku) was not spending its entire nominal income on wages, as it would appear. Many of the retainers at the bottom of the income scale may have been "part time samurai"- foot soldiers who farmed as well. Their stipend thus did not include their income from farming. This table is before any obligatory "loans" back to the han, so actual available income will have been less. At the end of the day, most samurai remained eternally broke.1 point

-

Hello, While the primary function of Hon'ami valuation was indeed for gift-giving purposes, there are extant records of masterworks trading for large amounts. This also surprised me, as I used to believe that these valuations were symbolic. It is an interesting topic and does confirm that beyond land and estates, swords were the most highly valued objects of their time. This is, of course, the tip of the iceberg. We can assume that vast majority of transactions went unrecorded for obvious reasons. The table below compiles from reliable sources recorded transfers of properties. # Meibutsu (English) Type / smith Approx. date of transaction (Edo) Buyer / recipient Seller / previous holder Nature of transaction Stated price Brief note on the deal Primary Japanese online source 1 Shinmi Rai Kunimitsu (新身来国光) Tantō, Rai Kunimitsu Mid-17th c. (Aizu Hoshina Masayuki’s time) Aizu lord Hoshina Masayuki (Hosokawa Masayuki / 保科正之) Unspecified (sword already famous) Purchase, later献上 to shogun 3,000 kan (purchase); later 200 mai as shogunal valuation Aizu lord buys the oversized Rai Kunimitsu tantō for 3,000 kan (“三千貫にて…お求め”) and later presents it to the Tokugawa shogun; the shogunal house then attaches a 200-mai valuation. meitou.info 名刀幻想辞典「新身来国光」 2 Ikeda Masamune (池田正宗) – purchase 1 Katana, Masamune attribution Late Momoyama / very early Edo (Toyotomi–early Tokugawa) Date Masamune (伊達政宗) Earlier, unspecified owner Purchase 1,000 kan Meibutsuchō excerpt: “伊達政宗卿千貫にて御求め” – Date Masamune buys the blade outright for 1,000 kan. meitou.info 名刀幻想辞典「池田正宗」 3 Ikeda Masamune – purchase 2 Same sword Same generation as above Ikeda Bitchū-no-kami (池田備中守輝政) Date Masamune Purchase (re-sale) Implied 1,000 kan (“同代にて御払ひ…御求め”) The text records that Date disposes of the sword in the same generation and Ikeda Bitchū-no-kami “御求め” (buys it), at what is clearly understood as the same 1,000-kan level. meitou.info 同上 4 Ikeda Masamune – shogunal acquisition Same sword Early Edo (2nd shōgun Hidetada) Tokugawa Hidetada, later Owari Tokugawa Ikeda Bitchū-no-kami Confiscation / purchase with price noted, then gift to Owari 1,000 kan “秀忠公また千貫に召上られ尾張殿拝領” – Hidetada “summons up” the sword at 1,000 kan and then grants it to the Owari house. Financially a shogunal buy-back followed by a gift. meitou.info+1 同上 5 Asai Ichimonji (浅井一文字) Tachi, Fukuoka/Ko-Ichimonji school c. late 17th–early 18th c. (after princess Matsu’s marriage, Hōei era) Matsudaira Mino-no-kami (Yanagisawa family) “Saishō-dono” (Maeda / courtier acting as sender from Kaga house) Paid transfer (“被遣”) 1,000 kan for that transfer (later 1,500 kan valuation in Yanagisawa hands) Meibutsuchō text: after Matsuhime’s marriage, “right blade was sent to Matsudaira Mino-no-kami at 1,000 kan” (“右刀千貫にて松平美濃守殿へ宰相殿より被遣”). Later in Yanagisawa ownership it rises to 1,500 kan. meitou.info 名刀幻想辞典「浅井一文字」 6 Kanze Masamune (観世正宗) – Ietsuna confiscation Wakizashi, Masamune attribution Kanbun era – Kansei 3–4 (1663–64) and later Shōgun Tokugawa Ietsuna (as acquirer) Echigo lord Sakai Mitsunaga line, via Honda Nakatsukasa-no-kami Forced re-acquisition with compensation 400 koban (“黄金四百枚拝領”) Long transmission note records multiple re-valuations (1,000, then 3,000 kan etc.). Eventually, in Kanbun/Kan’ei years, the shogunate seizes it back and the holder receives 400 koban in gold as compensation – a de facto compulsory purchase. meitou.info 名刀幻想辞典「観世正宗」 7 Nara-ya Sadamune (奈良屋貞宗) – merchant sale Tantō, Sadamune Bunroku era (1592–96, Toyotomi rule; technically very early Edo contextually) Toyotomi Hidenaga (“Kōmon Hidetoshi-kyō”) Merchant Naraya Sōetsu of Sakai (堺・奈良屋宗悦) Purchase, then献上 to Hideyoshi 500 kan Meibutsuchō citation: Sakai merchant Naraya owns the blade; in the Bunroku years “右貞宗を五百貫に黄門秀俊卿求め秀吉公へ上る” – Hidenaga buys it for 500 kan, then presents it to Hideyoshi; it later passes Hideyori → Hidetada → Owari, with documentary evidence of the original price still attached in Keian 3. meitou.info 名刀幻想辞典「奈良屋貞宗」 8 Togawa Shizu (戸川志津) – Maeda purchase Tantō, Shizu (志津兼氏) Early Edo (Keichō–Kan’ei; Maeda Toshinaga’s time) Maeda Toshinaga (利長卿) of Kaga Togawa Higo-no-kami (戸川肥後守) Purchase “Gold 130 coins or 1,000 ryō” (two alternative figures) The entry explains that Togawa Higo-no-kami once owned the piece; Maeda Toshinaga later “求む” (buys it) at “黄金百三十枚歟小判千両歟両様の中にて” – either 130 gold pieces or ca. 1,000 ryō. It is subsequently presented to Hidetada and re-valued at 100 mai, then moves via Kii Tokugawa and back to Owari. meitou.info+1 名刀幻想辞典「戸川志津」 9 Sayo Samonji (Sayo no Sayo-monji) (小夜左文字) – famine sale Tantō, Samonji (左文字) Kan’ei 4 (1627), Kokura famine Unspecified external purchasers (via intermediaries such as Doi Toshikatsu, according to later traditions) Hosokawa Tadatoshi (忠利), 2nd Kokura / later Kumamoto lord Emergency sale to raise famine relief funds Price not explicitly recorded in Meitou Gensō Jiten The meitou article notes that in Kan’ei 4, during the great famine in Kokura, Hosokawa Tadatoshi, to relieve his starving subjects, sold off the celebrated tantō “Sayo Samonji” together with the daimyō-grade tea caddy “Ariake / Ankokuji Katatsuki”. This is one of the clearest cases of a great meibutsu sword being liquidated in early Edo. meitou.info+1 名刀幻想辞典「小夜左文字」 10 Sayo Samonji – Yamauchi acquisition Same sword Late Azuchi–Momoyama / very early Edo Yamauchi Kazutoyo, lord of Kakegawa A local polisher (togishi) who had received/kept the blade Purchase (“買い上げて所有”) Price not given Before the Edo-period daimyō circulation, the same article relates that Yamauchi Kazutoyo bought the tantō from the sword-polisher in Kakegawa who had used it in the famous revenge episode; this is described explicitly as “研師から山内一豊が買い上げて所有”. meitou.info 同上 11 Ikoma Samonji (生駒左文字) – exchange & resale Katana, Samonji attribution Mid-17th c. (after transfer to Ogasawara) Honami house, then various daimyō Ogasawara clan finds it ill-omened Exchange (道具替え) and later resale (売買) No explicit price for the exchange; later 1,000 kan valuation in Honami origami The Ikoma Samonji is eventually considered unlucky; the Ogasawara family has Honami take it in exchange for another sword (“本阿弥家に渡し別の刀と交換した”), and the Honami house later sells it onward (“その後本阿弥家から他家に売買され”). This is a documented secondary-market transaction, even though the exact sum is not recorded. meitou.info 名刀幻想辞典「生駒左文字」 12 Kodama Masamune (小玉正宗) – transfer with prior purchase Tantō, Masamune attribution Early Edo (Keian era) Owari Tokugawa (Yoshinao), later Takasu-Matsudaira branch Naruse Hayato-no-shō family, earlier holder Gift / transfer “received from Naruse” with earlier 1,000-kan purchase on record 1,000 kan (折紙), earlier price 130 mai Entry gives “小玉正宗 無銘長八寸三分半 代千貫 尾張殿… 是ハ右兵衛督様御拝領 成瀬隼人正より請取”. The sword is in Owari hands with a 1,000-kan origami; it is explicitly said that Yoshinao received it from Naruse Hayato-no-shō. The earlier price of 130 mai is preserved in documents, making this a well-documented transfer, though the act from Naruse to Yoshinao is framed as “拝領” rather than a straight commercial sale. meitou.info+1 名刀幻想辞典「小玉正宗」1 point

-

1 point

-

Its difficult to make such analysis, because coins were devalued, prices fluctuated, 1710-1790 no one was buying any swords, koku stipends experienced both inflation and deflation, but I don't think two ryo stipend is something that was actually meant in the text. Generally a very good stipend was 150 koku. Top administrator for a top clan could make 500. The least stipend was often in 25-40 koku range, and in clans like Uesugi you were expected to have a side trade at this level. Hatamoto were more or less equivalent to a lesser clan serving a major Daimyo, so they are not one to one comparable to samurai. The main question was how much spare cash existed after expenditures, especially since the system typically aimed for "zero" as the answer. The system was also "Pareto" designed, with sharp boundaries between the classes without "in between" steps like 120 or 225 koku. Honami valuations are more or less fantastic rather than market based. Very few clans which could more or less consistently acquire swords at high level. Probably most exchanges involving such swords were not purchases, but gifts. In which case Honami valuation suggests the gift's value... Very good modern sword would more often than not be under 10 Ryo, quite affordable for the upper administration. Then again the real market prices (i.e. pawn shops) constantly fluctuated and what would be taken as collateral at 100 Ryo in 1700 and in 1740 would be very-very different amount of material.1 point

-

As a regular resident of the Tosogu section I just purchased my first blade (about 2-3 hours ago at time of writing this post) and wanted to share with the forum! The blade is a hozon certified kinnoto (imperial royalist sword) from the Gassan school dated August 1863 by Unzenshi Sadahide. It is a very large katana with a 75cm blade and 27cm nakago. The blade has a lot of weight and thickness to it, I'd say about twice as heavy as an average katana. Aside from the size and heritage of the sword, I really like the lengthy kissaki as well. The blade should make for a fun koshirae project in the future! Let me know your thoughts, I am still a novice when it comes to blades! Here are a few photos:1 point

-

Chino, You might already know, but the small stamp at top, Showa stamp, was an inspector stamp of the civilian Seki Cutlery Manufacturers Association. They tend to be really nicely made. The date range is 1935 - 1942, with most dated blades found 1940-1941. Could you post a shot of the full rig showing the fittings?1 point

-

1 point

This leaderboard is set to Johannesburg/GMT+02:00

.jpg.30ab2d83eefb0b6e4124f21ac7160fe7.jpg)

.thumb.png.4c5df79fec171b2dc4a23af38e280a4d.png)