-

Posts

963 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

4

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Steve Waszak

-

Sounds good, David. Talk to you soon. By the way, here's a link to the book in question on Grey's site: https://www.japaneseswordbooksandtsuba.com/store/books/b952-nobuiye-tsuba-full-translation

-

Oldest piece of Japanese art

Steve Waszak replied to kissakai's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

I am not very knowledgeable when it comes to pre-Momoyama tsuba, so I am happy to defer to those who are. From what you say about Sasano, Grev, it seems this may even be as early as Kamakura Period, then. I suppose Nambokucho to early-Muromachi is the "safer" bet. -

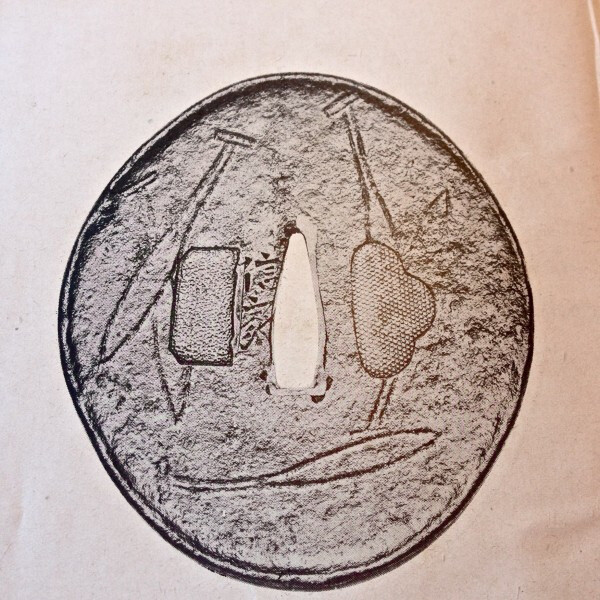

Hi David, Nobuiye is, of course, a complicated and contentious subject in tosogu studies. For anyone with a serious interest in pursuing this specialized area, I would highly recommend acquiring the Nobuiye Tsuba Shu by Iida. This book focuses entirely on Nobuiye, and the rubbings, photos, and essays on the appreciation, study, and evaluation of Nobuiye works are especially valuable. The essay by Katsuya Toshikazu is particularly excellent, offering extremely detailed analysis of Nobuiye sword guards, including tightly-focused examination of the sugata, the hira-ji, and of course, the mei. I believe that if you get this book and read the essays, you'll have a better idea about which Nobuiye may have made your tsuba. In my opinion, this is an early piece, but it is not by one of the two great masters comprising the first generations. Several things lead me to this conclusion, including aspects of the sugata, the hiraji, and the mei itself. While I agree with you and Dale in principle regarding the fluidity of artists' signatures, three things I think should be kept in mind. First, there is, perhaps, a meaningful difference between the way a painter/graphic artist may sign his or her works -- using a a brush or a pen -- and the way a metal smith might, using a chisel. The latter, of course, is a much slower process, and allows for much more time to be taken to locate with precision where the strokes will be placed, their angles, depth, length, relation to one another, etc... Second, in a culture as "calligraphically conscious" as the upper-class Japanese (for whom Nobuiye tsuba were certainly meant), there may be (have been) much greater sensitivity/awareness in general as concerns the presentation of a mei. The very fact that these early tsuba were among the first even to be signed at least suggests the possibility that mei presentation mattered to some degree, and so, it seems rather unlikely to me that mei would have been "slapped on" cavalierly. Finally, even within artists' signatures' variations, there are often certain consistent tendencies that remain among the evolving iterations. It is part of the "art of mei study" to become sensitive to how these manifest in a given artist's work, subtle though they may be. In your tsuba, David, I see at least three elements of the mei that strike me as a bit "off" for a would-be futoji-mei signature (it is clear that the mei is of the futoji-mei variety, and not that of the hosoji-mei/hanare-mei Nobuiye). While any one of these three could be brushed off fairly easily as anomalous, two bring more doubt, and all three have me deciding, based on mei alone (which I certainly wouldn't consider by itself), that the sword guard is not a true futoji-mei tsuba (That it could be the work of a student of a later (early-Edo) Nobuiye workshop, however, seems entirely plausible to me). Of the three points of concern, one is present in the "Nobu" ji, one in the "iye" ji, and one in both. I am happy to discuss this further with you, David, so please feel free to PM me if you like. We could also discuss certain "issues" with the sugata of your tsuba, as well as of the hira-ji. I like your tsuba; I think it's a good early piece, and the subtle workmanship of the kikko pattern on the hira of the mimi is a good sign. It could be a futoji-mei work, but as I say, I have my doubts. Cheers, Steve P.S. Below are some examples of futoji-mei Nobuiye tsuba, just for reference...

-

Oldest piece of Japanese art

Steve Waszak replied to kissakai's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

I think my oldest piece is this one, a bronze tsuba dating conservatively to mid-Muromachi I believe, though at least one person with far more experience on very early tosogu has said it could be or even likely is Nambokucho/early-Muromachi. Bronze sword guards are not very common, and they would seem to have been in favor in earlier (than mid-Muromachi) times. At 4mm in thickness, this tsuba is very heavy, has a deep patina, and as can be seen, presents with plenty of remnant black lacquer. -

As is true for so many things aesthetic, the Japanese have a term for the interplay between positive and negative space: Nohtan (濃淡) The content in the link below focuses on nohtan in painting, but it's worth thinking about how the term and concept apply to sukashi tsuba design. https://drawpaintacademy.com/notan/

-

My views include utsushi, yes, if we are speaking of utsushi of original early tsuba that many would agree are masterworks borne of the dynamics of their time. In saying this, and in saying what I will below, I am assuming that by "prototype," Terry means an original work (design, treatment, etc...) created by a highly worthy, if not master smith. After all, i doubt we would use such a term to refer to just any old early sword guard ("prototype" wouldn't really fit, then, would it?). Likewise, I don't suppose we would see many utsushi being made of mediocre pieces... Dale, you make a distinction between "mere copies," on the one hand, and (works) "emulating the spirit (of the original)," on the other. I'm not quite sure I see a clear, actually effective difference here. If the "spirit" of a work can even be perceived and felt (this does get a little mataphysical), how would/could that be "emulated"? The form of a work can be emulated or copied, and the same material used, the same motifs, etc.... But a great deal of the vitality, the energy, the power of a master work is generated from the circumstances of the artist/smith who makes it, both personal and cultural. This, I would say, is a big part of the "spirit" we (believe we) sense when we encounter and connect with their work. The sheer act of copying, or emulation, must immediately be lacking in that same spirit, if for no other reason than because that later artist's own unadulterated individual spirit and the cultural zeitgeist giving rise to him/her is not present in the emulation (or if it is, it is necessarily watered down). This leaves us with only the copy, then, that is, the form, the design, the motif, even the surface finish...the sum of the parts, perhaps, but far from the whole. Your quote from Wikipedia is intriguing, too. When it asserts, though, that "Utsushi promotes a dialogue between the artist and the masters of the past, connecting past, present, and future," it is being generous in calling the interchange a "dialogue." A dialogue should be understood, I think, as an exchange between equals. An artist copying/emulating the work of a past master cannot in doing this equal that master's work for the reasons I give above. So, this "connecting" that the quote mentions is more along the lines of derivation than it is any sort of exchange between equals. Which is to say, as we move from "past" to "present" to "future," what we get is an increasingly watered down version of the original, due to what is lost in derivation. Perhaps "homage" is a better term to describe the efforts of the artist creating the utsushi, since these efforts are, I believe, inspired by a profound respect and admiration for the original work being honored. Even this term, though connotes, if not denotes, a tacit admission of at least some derivation in the resulting work, I would say. Having said this, I need to make a distinction, too, between the work of a later artist simply copying/emulating/"homage-ing" that of the earlier master, and the work of a later artist expanding from what that earlier master expressed in his work. We can find good examples of this in certain tsubako groups, where a later smith generated his own ideas based on the potent sensibilities of the earlier smith(s), and produced work quite original to him, while still retaining the character of the original (I can think here of the tsuba of the "Nidai" Yamakichibei and the Sandai Shimizu Jingo as two such examples). One good case study in this discussion might be the Norisuke tsubako of 19th-century Owari. Both generations were/are celebrated for their utsushi, but these utsushi do not come close to the original masterpieces they paid homage to. They are very skillfully done, to be sure, but they are missing that resonant vitality so palpable in the originals. Their own original designs, though, sometimes do possess this strength, much more so than any of their utsushi (in my opinion, of course). Anyway, it's an interesting topic, Dale. Thanks for bringing in that quote. By the way, I'd be very curious to see any examples that could be provided of an utsushi that might illustrate Terry's words as presented in his quote. I do wonder what Terry would see as just such a "groping prototype," as well as what he then would present as a later work that is a "much superior" example of that prototype. Perhaps I am missing entirely what he intended to express... Steve

-

"In this connection it is worth remembering that many modern works of art are in reality much superior to those of the past. The present-day craftsman is often much defter than his groping prototype, and where equally good materials are employed, new work is not infrequently preferable to the old." Dale, This is an interesting opinion. I'm sure there must be examples to suggest the truth of it; however, we should also recognize that frequently, not just sometimes, the "groping prototype" exudes originality and the potent vitality that accompanies it, while the "defter present-day" craftsman's "much superior" work, despite this deftness, comes across as lifeless. We all value various characteristics and aspects of art differently, of course. So, for those who see mastery of intricacy and super-human abilities in the fine detailing and flawless finishing of a piece as the zenith of artistic achievement, "superior artistry" is thus realized, and we may see this in the present-day craftsman. But for those of use who, while still appreciating the technical virtuosity of such works, strongly prefer the resonant energy of the "groping prototype," the (much) superior art is to be found in this latter. I might add here that something profound is lost when "present-day craftsm[e]n," however technically skilled, produce works that simply copy the designs of the "groping" artist whose works emerged organically, and with piercing resonance, out of the zeitgeist of a time and place. The resulting authenticity of the latter, with vanishingly few exceptions, simply cannot be captured by the former, regardless of his "superior" abilities.

-

Thanks, again, Piers. Much appreciated.

-

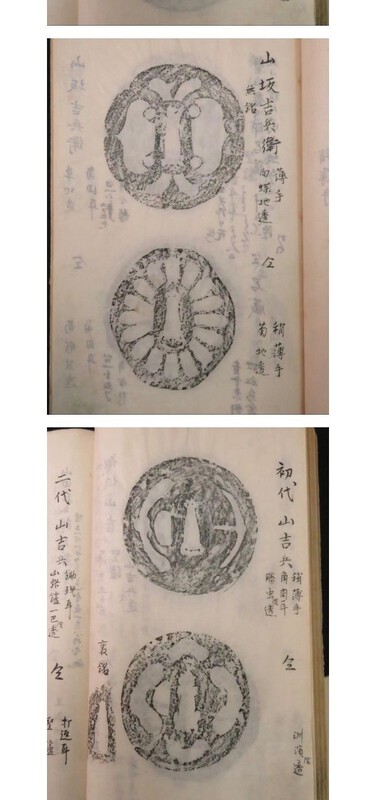

Thanks, Piers! Would you be able to confirm if that lone kanji in between the two tsuba-and-text means something like "the same"? And I'm guessing that for the second tsuba, "kiku" would be one of the kanji? Thanks again.

-

Looking to have the writing accompanying the upper two (Yamasaka Kichibei) tsuba translated. If anyone could assist, I'd really appreciate it! I can read a little of it (like the artist's name), but much I can't make out. Thanks for any help! Cheers, Steve P.S. A bonus would be having the writing on the other side of the page translated, too, some of which can be made out through the paper...

-

Thanks for posting these, Lance. I can't help but wonder, though, whether inferences were made after observing the few and then applying that "knowledge" to the whole. Quite a few generalities here. Then, too, if the point made at the end of the second video regarding the ambiguous nature of Japanese language and communication is to be taken as true/accurate, how can the European account be confident of its understanding of the Japanese? After all, a use of language that prizes ambiguity and indirectness would seem likely to give rise to misunderstandings. Still, these presentations of first contact and early interaction of cultures so alien to one another are always fascinating. I recommend the various Michael Cooper publications, such as This Island of Japan: Joao Rodrigues' Account of 16th-Century Japan, and They Came to Japan: An Anthology of European Reports on Japan, 1543-1640. So often, we get our "knowledge" of early Japan from publications that date to centuries after the period they're focused on. But how does such passage of time and evolution of culture distort the veracity of what is reported? First-hand reports, though, while obviously not immune to biases and misapprehensions, offer at least the impressions of those who were there at the time, and perhaps a somewhat more accurate account of the period and place in question. They are really intriguing reading, if first/early-contact narratives are of interest.

-

Jean, Hmmm... "technical requirements"? This term would have to point to practical applications such as the basic purpose of a sword guard, no? If so, a distinction needs to be made, as I said in my first post, between such practical applications, on the one hand, and aesthetic purposes/considerations, on the other. Trying to combine these or failing to distinguish between them will lead to a convoluted discussion, I think. My recent post had entirely to do with the latter -- aesthetics. That the tsuba I posted images of might or would also satisfy effectively "technical demands" was not my aim in posting them. So in addressing the question of what a "good iron" tsuba is, for purposes of this discussion, I am mentioning only those aspects or features which contribute (in my opinion) to making a given tsuba "good" as far as its iron is concerned. And I have already mentioned them: elements such as masterful forging and hammering, application of yakite-shitate, the presence of sensitively realized tekkotsu, the color of the metal, and the patina the steel takes on, ALL contribute to what makes an iron/steel tsuba "good." And "good" in my eyes, only, I must emphasize, as we are talking largely, if not entirely about taste, from a necessarily subjective perspective. Again, when looking at the aesthetic aspect, subjectivity rules; when looking at the "technical requirements" aspect -- the practical applications/considerations -- things can be much more if not wholly objective. For those who think that tekkotsu is clumsy, or that a yakite finish creates a "smeary muddiness" on the surface, or that anything but a perfectly polished surface comes across as clunky and uncouth, tsuba such as those made by Hayashi Matashichi would certainly be "better" than those coming out of Owari. And such a viewpoint is, needless to say, perfectly valid. But again, we're talking about TASTE, and taste is a very personal, and obviously subjective thing. So your post above is one that I find a little confusing to try to address, since it seems you're alluding to the possibility of arriving at objective criteria for a category of assessment that is dependent on subjective appreciation. I have to run here just now, but later, I can provide images of what I would consider to be beautifully-forged steel, which for me is one of the chief criteria for what makes a tsuba good/great. Cheers, Steve

-

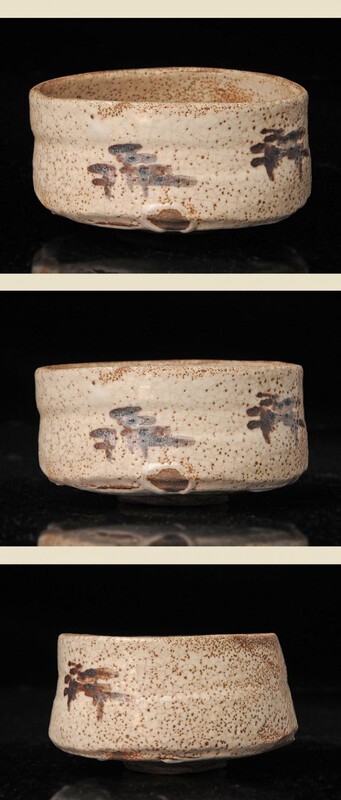

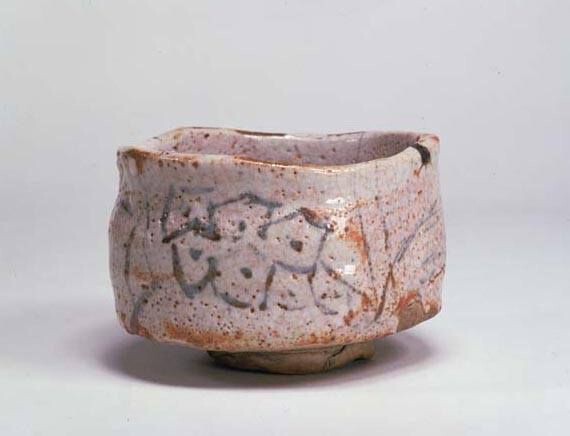

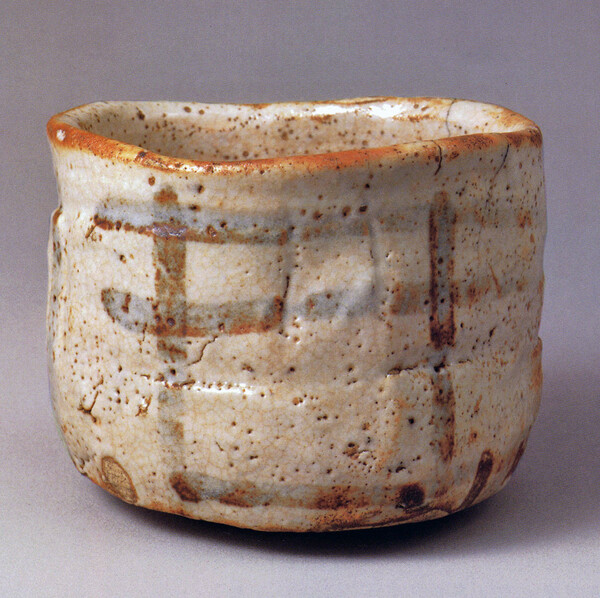

Hi Pietro, Well, there are several things to note here on why this piece is pretty clearly not of the Momoyama years. The shape is not in keeping with the usual Mino/Shino expression of the turn of the 17th century. Momoyama Shino ware will usually have a more elongated and distorted or "warped" shape to it, irregular, with a rim that is far from so "perfectly" formed and round as we see in the piece you posted. The rims on Momoyama Mino ware, including Shino will have a highly irregular form, and often will be missing glaze here and there along the edge. The glaze, too, is wrong for the period on the bowl you posted. It is much too new looking, lacking in depth and in any sort of "patina." While it's true that pottery doesn't quite take on a patina like ivory or iron will, there is still a richness to the surface borne of those centuries that more newly formed objects don't seem to reach. I can say that in my experience, anyway, I have yet to see a more recently-made ceramic (under 100 years old) carry the same "luster" that a 400-year-old chawan (that was used) will have. Further, the glaze on "your" bowl is lacking any imperfections, damage, scuffs, chips, etc... Again, too perfect. And the color of Momoyama Shino is a hard-to-describe creamy white that is not so bright white as we see with newer Shino pieces; additionally, newly-made Shino ware often goes over the top with its translucence and milkiness. Real Shino works from Momoyama times have that mellow creamy-white punctuated with imperfections, bare patches, etc... And very important to note: real Momoyama Shino chawan will often present with that skin-of-an-orange "pitting" all over the surface. When this is juxtaposed with the reddish hues coming through the creamy-white glaze, you get a pretty iconic Momoyama Shino look. Finally, the foot on the bowl you posted does not exhibit the type of clay I would usually expect to see revealed on the foot of a Period piece. Have a look at the images here. These are all Period Shino chawan. One of them might be recognizable as a National Treasure piece. Compare the clay, the foot, the glaze, and the form of the bowl, the rim, etc... on this piece to the bowl in question. Big, BIG difference. Cheers, Steve

-

lol... Thanks, Pietro. Moved too quickly to answer you to remember the link! Looking at those photos, I would say no, not of the period. Several details point away from that, I think. Certainly inspired by the period, though...

-

Hi Pietro, Really need to see the foot of the bowl to start to have a better idea if it could be period...

-

They say a picture is worth a thousand words... Thought I'd throw a few thousand words into the conversation... #1 Shodai (Hanare-mei) Nobuie #2 Shodai Nobuie #3 Nidai (Futoji-mei) Nobuie #4 Nidai Nobuie #5 Yamasaka Kichibei #6 Yamasaka Kichibei #7 Yamasaka Kichibei #8 Meijin-Shodai Yamakichibei #9 Shodai Sadahiro #10 Shodai Hoan #11 Nidai Yamakichibei

-

Hmmm... "Best" is a tricky term here. Are you thinking mostly in terms of aesthetics or of more objectively practical considerations (corrosion resistance, ability to withstand blows, etc...)? Of course, these needn't be entirely mutually exclusive. For my money, while Higo metal is renowned for its aesthetic magnificence, it is the steel guards from Owari Province that impress the most. The forging, hammering, finishing, color, and patina found in works made by the early (genuine) Nobuiye, Yamakichibei, Hoan, and Sadahiro tsubako, together with early Owari sukashi and Kanayama tsuba outclasses all others (in my opinion only, of course ). In the years I've spend studying and collecting almost exclusively early steel sword guards, my conclusions on this have only become firmer. Other excellent traditions include Ko-Shoami works, as well as early Saotome and Tembo, and some of those tsuba called "Ko-Tosho" and "Ko-Katchushi," but none of these can match the best from Owari, in my view. Again, "best" is a term that needs some clarification. Without that, it's difficult to proceed with the discussion.

-

Greetings all, Just wanted to offer a heads-up here regarding some new listings on Elliott Long's Shibuiswords.com site. They concern a number of Yamakichibei sword guards that he is offering, some of which I used to own. Others of them passed through my hands without ever belonging to me (unfortunately) . They are worth a good look, so please check them out. None of these belong to me now, so I have no horse in the race here. If anyone would like to discuss any of these tsuba with me, I would be happy to do so. Just PM me. http://www.shibuiswords.com/tsuba.htm#yamakichibei Cheers, Steve

-

Really too bad. Never a problem with them. Always quick, polite correspondence, excellent service. Sigh...

-

Ah, yes, I hadn't scrolled down far enough to catch the dimensions. Thanks, Pietro. Yes, these dimensions are in keeping with what I would expect from an actual period bowl. Revival works usually have a smaller diameter across the rim, often 12cm or less. All considered --including photos of the rim (thanks for these, Ed) -- and working only from photos, I would say with some if not full confidence that this is a Momoyama Period work. Beautiful chawan. A couple of years ago, there was another Momoyama Kuro-Oribe chawan that went for nearly 3.5 million yen. It was spectacular. Kind of amazing they're ever available at all, really... Cheers, Steve

-

Hi Ed, I know the feeling. All too well. My sympathies. There was a Yamakichibei tsuba up for auction once. A really good one. I put a really good bid on it, which turned out to be laughably inadequate (it ended at over a million yen, just as this chawan did). This bowl does seem to be a worthy piece all right (would still like to see photos of the rim, though, as well as to know the dimensions, as later "homage" works are often significantly smaller than the real thing). Thanks for these extra photos. Actual Period Kuro-Oribe chawan available for acquisition are very rarely encountered, in my experience. Thanks for posting this, Ed. Cheers, Steve

-

Ed, Thanks for posting. Do you have any other photos of this chawan? Dimensions? I'm wondering if this is really Momoyama... Cheers, Steve

-

Thinking of you, Ford. Really sorry to hear this, needless to say, and wishing you the best. Very glad you're getting the attention necessary: that's not something to take lightly and brush off. And really sorry to hear of the negativity you've had to endure. Here's hoping that these weeks of rest will bring some clarity in any areas it may be sought. Cheers, mate. Steve

-

Nobuie. Steel. 8.2 cm. Yattsu Mokko-gata. The thickness of the tsuba swells considerably from the nakago-ana (4 mm) to the mimi (6 mm), creating an "expansive" effect to the motif, which I believe to be a stylized lotus blossom. Tsuchime-finished surface. The signature is of the type that is referred to as "Futoji-mei," attributed by most scholars to Nidai Nobuie. I do not know if the plugs are solid gold or another material with a gold sheeting applied. Momoyama Period.

- 408 replies

-

- 10

-

-

-

Definitely not THE Nobuie, but what do you think?

Steve Waszak replied to Katsujinken's topic in Tosogu

...and let us remember, too: sometimes, it really is only the bath water that needs to be thrown out, rather than the baby, the soap, and the whole damn tub. :beer: