-

Posts

825 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

3

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Steve Waszak

-

Hi Sebastien, I do believe such rankings exist in at least a couple of Japanese publications, but the only one I have seen recently and which I found most intriguing was a "Banzuke" ranking list Markus Sesko published in his blog post of October 2, 2016. I highly recommend locating and reading this post. Markus references this banzuke, noting that it is titled Tohken Tsuba Kagami and that it was compiled by Noda Takaaki, a sword-fittings expert, in the early 19th century. What I find especially interesting here is to see how various tsubako that have certain reputations now were viewed 200 years ago. Markus observes that this ranking list seems to focus only on tsuba artists working in iron, as it excludes kinko artists. I, too, would be interesting in knowing about any other specific publications which provide such ranking lists, especially for iron/steel tsuba. Cheers, Steve

-

Restoration Of Tosogu, Nihonto, Etc...

Steve Waszak replied to Steve Waszak's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Gents, Some excellent thoughts expressed here in your posts. They are much appreciated. Henry, thanks for clarifying what you'd meant by change. Yes, I see now what you mean. I do wonder now if part of my initial question wasn't really at heart concerned with the tension (and confusion?) between the terms "restoration" and "conservation." I got the ball rolling in an unhelpful direction by referring to the treatment of the Velazquez painting as a "restoration," while the term "conservation" was used in the article itself. I suppose I had been assuming that conserving something had mostly to do with preserving it in its current state (i.e. before any [further] damage could befall it), and that restoration meant more of an active intervention to "undo" the ravages of time (and prior actions), and so I saw the treatment of the Velazquez as an effort to "restore" the painting to something approximating its original appearance. I appreciate, too, Henry, what you have to say about conservators/restorers looking to preserved examples of similar pieces as guidelines for a treatment process. This would assume, though, that these preserved examples (in shrines, for instance) are themselves in "proper" condition (which kind of gets back to my initial query ). But yes, I can see where if such "model examples" do exist, that would provide an excellent blueprint for how to proceed and the goal to be sought. Jean, I appreciate your comment in the last sentence of your post concerning the restoration/conservation possibilities in the case of an iron tsuba that has been heavily corroded. While the condition of the piece might be improved, it would seem impossible, as you say, to bring the guard back to anything very close to its original state. One quick side comment here on the rarity of Kaneie tsuba: I think what Henry and I are referring to when we speak of this rarity are O-shodai Joshu Kaneie tsuba, of which I believe only five are thought to exist. Personally, I don't consider the Edo Period "Kaneie" works to be true Kaneie tsuba. Jason, your thoughts on eras and cultural differences are definitely thought-provoking, too. Thanks. But I wonder if there might be a difference in our discussion here between swords (and their purpose, including mysticism and functionality) and, say, an iron tsuba, when it comes to questions of conservation/restoration. Once again, thanks, guys, for your posts in this thread. Lots to think about... Cheers, Steve -

Restoration Of Tosogu, Nihonto, Etc...

Steve Waszak replied to Steve Waszak's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Henry, Thanks for the post. You express some interesting thoughts and sentiments here, which I shall ponder further. To respond briefly to a few of these, first, yes, I have asked too many questions. Apologies. But thank you for underscoring the distinction between conservation and restoration. I think this is a worthwhile difference to note, but ultimately, I'm not quite sure it speaks to the core question I'm asking, which has more to do with how we know what state an object "ought" to be in (and who has the "authority" to determine this). Actually, the penultimate paragraph from the article by Frank Matero you linked us to, Henry (thanks for that, too, by the way), more or less zeroes in on that question. I have reproduced this paragraph below: "Within the contemporary discipline of conservation, it is possible to find any number of incompatible, diametrically opposed viewpoints and work methods—from the idealist one that hopes for an impossible return of the object, structure, or site to an origin that can never be established with any certainty, to the pragmatic one that permissively treats as historical values all the alterations made over time. To this must be added the recognition of cultural and community ownership and the input of those other interested groups in the decision-making processes that remain the primary responsibility of the profession." (Matero) In this paragraph, Matero stresses two "incompatible, diametrically opposed viewpoints and work methods" in contemporary conservation dialectics. It is these viewpoints/work methods that particularly interest me. The initial link I put up---to the Velazquez restoration---clearly describes a restoration (rather than a conservation) effort (according to the definitions/descriptions you have in your post, Henry ), and would seem to lean, anyway, towards the first of the two possibilities Matero offers---the "'idealist' one that hopes for an 'impossible' return of the object...to an origin that can never be established with any certainty..." Of course, the restoration of the Velazquez painting is not really an effort to return it to its literally pristine original state, but the effort does seem to be much more in keeping with this sentiment than the other of Matero's possibilities, that of a "pragmatic [approach] that permissively treats as historical values all the alterations [e.g. layers of varnish] made over time." This latter approach/sentiment would seem to "appreciate" the condition of the Kaneie tsuba I posted images of. I guess I'm wondering how it is determined that a privileging of original-state idealism (in the case of the Velazquez restoration) is to be preferred over an "appreciation" of historically accrued alteration (i.e. several layers of varnish). Mind you, I'm not saying there's anything wrong with preferring the former (far from it, actually); I'm just very curious as to the thought process here and how relative values are prioritized. Henry, you'd also said that "for the past to be relevant it must be framed in the present and this continuity and relevance is established through change." I was a bit confused by your words here, though: by "change," did you mean that the object under conservation efforts would be physically changed/altered? Part of my confusion might be because framing something from the past in present contexts and perspectives is one thing (it does not require physical alteration of an object), but literally changing an object (physically manipulating it) is another, I think. But I could be misreading, so some clarification here would be appreciated. Many thanks again for your post, Henry. Cheers, Steve -

Restoration Of Tosogu, Nihonto, Etc...

Steve Waszak replied to Steve Waszak's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

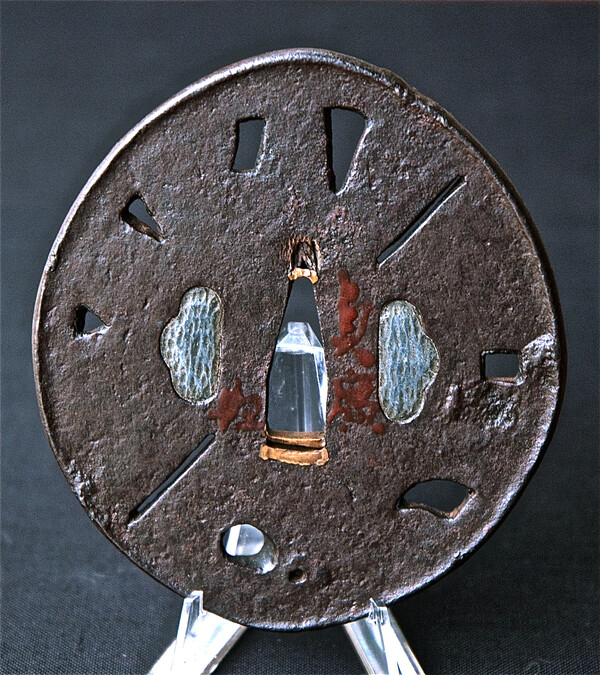

Many thanks to all for your well-considered replies here. I find this topic to be rather vexing, for it introduces such pointed philosophical questions: to conserve or restore? Or, is this a false dichotomy? Is restoration a form of conservation? What, exactly, are/should we be conserving? Artist intent? Can this really be known 400 years later? Or are/should we be conserving a particular state of signs of aging? What if these two contradict? Which are we prizing more highly, the vision of the artist or the state of the object (assuming for argument's sake that these do not align)? Such questions are made even more complicated when we consider others: if restoration is decided to be the better path, this path is fraught with various perils. What is the sensibility of the restorer? What should/"should" this sensibility align with? The intent of the artist? A specific idealized state of signs of aging (e.g. patina)? The desires of the current owner of the object that it look a certain way? A particular "consensus" of "expert" opinion on how such objects should look or the condition they should be preserved in? What are the skills of the restorer irrespective of his sensibilities? And do we, as temporary holders of these objects, have the right or license to act on or alter their state/condition? What if good-faith attempts to properly preserve or conserve them ends up causing (more) damage to them, such as can occur when, in efforts to preserve a patina, we allow corrosive rust to eat away at the surface of the piece? I apologize for dumping so many questions here at once. If I may try to simplify matters, I guess the basic tension I am asking about concerns artistic intent as a primary value, on the one hand, and signs of graceful aging as a primary value, on the other. I have seen iron tsuba, for instance, which present with various substances on the plate. These can range from lacquer and wax to oil, paint, and shoe polish, in addition of course to rust and dirt. Of course, we might agree that some of this material should be removed. But if none of this material was intended to be there by the artist, should(n't) all of it be removed? What if attempts to do so damage whatever good patina is under all that gunk? Some might say that the threat to the patina makes such attempts too risky, and that they ought not be undertaken. But then, if we can't even see that patina (never mind the fine details rendered by the artist originally), what good is that patina (in terms of aesthetic appreciation)? *Note: I will leave the question of whether a "perfect" 400-year-old patina, which is not what the artist "intended" when the object left his workshop, doesn't then actually occlude our apprehension of artist intent... It is easy enough, I suppose, to address questions of conservation (vs. restoration) if that tsuba is in an ideal state (i.e. all intended details of the artist are preserved [except, perhaps, the specific original color, which we can't pretend to know some several centuries later], and there is a deep patina across the entire surface, with no rust evident). When this "best of both worlds" is the state of things, most are probably pretty happy with matters. But what if we are confronted with an important steel tsuba that does not present in such a state? Below is a tsuba, made by Kaneie. It is considered by some to be the most important tsuba in existence, and by many others to be among the most important. How would you describe/assess its condition in these photos? Ideal? Acceptable? Unacceptable? It seems to me that, given the lofty reputation of this piece, and given that it exists in a situation (part of hugely important collection in Japan) with plenty of access to restoration resources, its state of preservation ought to approach the ideal. Would we agree that it has been preserved such? *I have included two versions of the photo, one with enhanced color to show better areas of rust on the plate. Thanks for indulging my OCD query... Steve -

Gents, I wanted to present a link to a short piece on the restoration of Velazquez's Portrait of a Young Girl (Ca. 1649) because I think it raises interesting questions pertinent to our interests in nihonto, tosogu, katchu, etc... Here is the link: http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2016/velazquez-portraits/portrait-of-a-young-girl I am certainly not posting here in order to flame or be a troll on this subject. Rather, the subject of restoration invites intriguing philosophical, aesthetic, and historical questions and pondering. Too often, it seems to me, viewpoints on restoration are perhaps too rigid or close-minded, and/or are arrived at by uncritically examining the position of various authorities (or "authorities") on the matter, without investigating the assumptions, values, or beliefs held by those individuals. So, as concerns this Valazquez painting and its restoration, I would like to invite a discussion on where, why, and to what degree the approach taken in the restoration of this painting might differ or be similar to that taken in the restoration of, say, an important early steel tsuba. For instance, are there any here who might object to any (or all of) of the restoration undertaken with this painting? Are there any who would hold the position that the accrual of the material (dis)coloring the canvas should be seen as a positive thing, worthy of appreciation? Or, would all agree that the restoration was necessary and/or a positive action? Again, I am not seeking to bait anyone or lay a trap . I am genuinely interested in the philosophies involved in questions of restoration and its methods, degrees, and which objects could/should be considered for restoration, and why. In returning to that important early steel tsuba (let's make it a Kaneie, for ease of reference), then, if that tsuba presented in a condition effectively analogous to the Velazquez painting prior to any restoration (as seen in the link), would we "leave well enough alone," or perhaps even appreciate the various layers of material as signs of the "beauty of aging"? Would we remove some of these layers but not all? If so, how would we decide how far to go with this, and based on what values/beliefs? Or would we look to achieve the effective equivalent of the end result of restoration process with the Velazquez, and remove as much of that material covering the original canvas as possible? If so, why? If not, why not. I would appreciate it if we could keep this discussion as civil and academic as possible... And I look forward to others' thoughts on this. Cheers, Steve

-

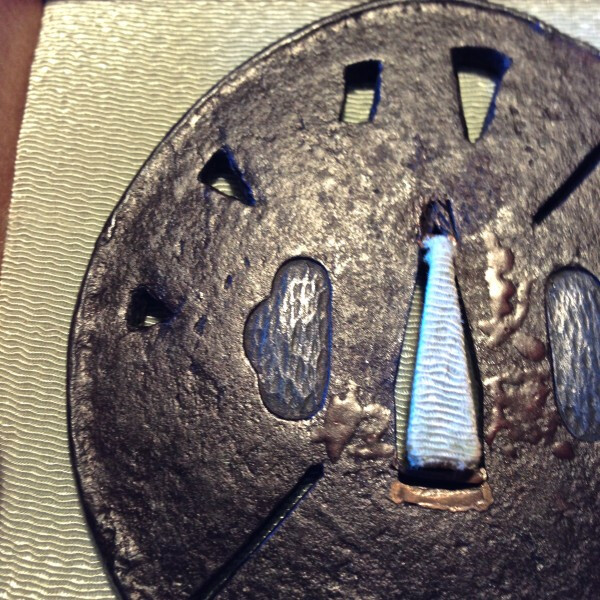

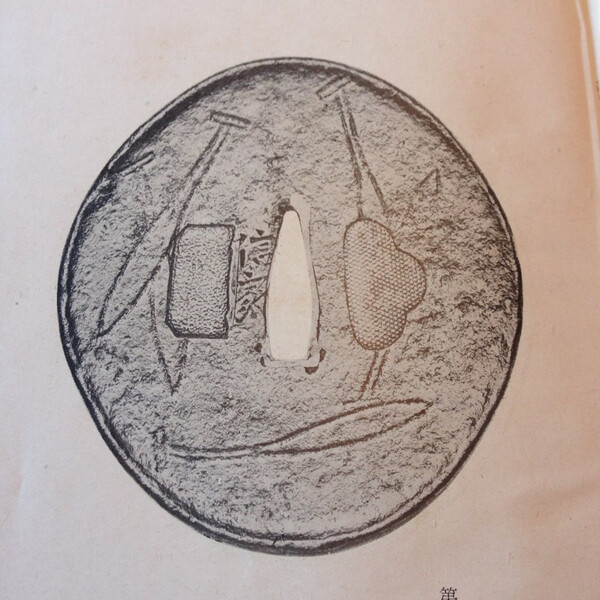

I have a tsuba that has been attributed, both by the NTHK and via shumei (don't know who did the shumei), to Sadahiro (Owari). I had the tsuba for more than two years before one day, turning the guard in the light, I saw what is an "abraded" or almost-erased Nobuiye mei. The signature is of the Futoji-mei variety, and what remains of it (the "Nobu" ji is still visible; the "ie" ji is essentially scrubbed away) confirms the particular style of rendering that ji that the nidai Nobuiye employed (some scholars have this artist as the shodai, but most, I believe, recognize him as the nidai). I have been perplexed as to why there would have been an attempt to remove the mei, unless some previous owner considered it gimei. A shame, since the piece itself is clearly---according to many production details---genuine nidai work. Here are photos of the tsuba, including close-up images of the seppa-dai. I have also included photos of two similar guards made by nidai Nobuiye (first two images). The "journeys" these works take over time is fascinating... Cheers, Steve

-

Always enjoy and appreciate your posts, Darcy. Thanks.

-

Insurance And On Site Security

Steve Waszak replied to GARY WORTHAM's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

My home defense consists mostly of these... Few thieves are desperate enough to try getting past two or three well-trained mastiffs... They are amazing, loyal, protective dogs. They're also on patrol 24/7, hear and smell anything amiss, weigh some 70-80kg each, and will guard the home with their lives. -

Thanks for the good tip, Peter.

-

Fantastic! Thanks, Markus. Really looking forward to it. I will definitely be getting a hard copy from Lulu, too... Cheers! Steve P.S. I hope you're recovering well from you back procedure...

-

Great to hear. Thanks, Markus!

-

Terrific stuff, Ford.

-

Evan, Nice tsuba. Really good to see a fine early iron guard here. My initial thoughts would be Owari, as the motif, the symmetry, and the rim style all speak to Owari sukashi. Probably early Edo, judging by the finish (little to no bold tekkotsu) and the kogai hitsuana. Good pick-up, Evan. Cheers, Steve

-

Markus, Many thanks for the post. I'm sure we're all looking forward to the finished product, but first things first: recover, get your health back. This is the priority. I'm sure it feels good to have the surgery behind you; now it's the recovery process, one step at a time. There's no rush, just get well soon. Cheers, Steve

-

Very best wishes, Markus. Back surgery is not a lot of fun (been there), but once it's over, you'll be quickly on the road to recovery. Then we'll expect three books a year. Take care, Steve

-

Alan, You raise some very good questions here. I haven't sufficient knowledge in this area to offer a useful comment, but I hope that your questions elicit some good responses. Cheers, Steve

-

This fascinatingly peculiar tsuba has been reduced to $375...

-

My guess is that both of these are 19th-century Bakumatsu Period revivalist pieces. The mei in both cases seeks to copy that of the shodai (hanare-mei) of the Momoyama Period, but details in the way the mei is done indicate it isn't that of the master. Of course, the work itself departs considerably from what we see in the shodai and nidai. 19th-century revivalist works often copied the great tsubako of much earlier times (Nobuie was a popular target), sometimes combining motifs and other features (rim structure, dimensions, etc...) into one tsuba but frequently overdoing it. IMHO, these pieces here are "valid" works in their own right (i.e. they are products of their time, forged rather than cast, and appear serviceable) , but perhaps not brilliant examples of tsuba art. Cheers, Steve

-

Perhaps not either/or, but influenced by both?

-

Addendum: I have heard from a seasoned connoisseur that this tsuba is likely to be a Namban variant or at least to display strong Namban influence. While I am far from knowledgeable about Namban(-influenced) tsuba, this possibility does seem to have some merit.

-

Thanks for those ideas, guys. As I say, this tsuba is kind of a head-scratcher for me. I certainly can see the earlier traditions being "represented" here, but aspects of the tsuba---the nunome, that intriguing area around the seppa-dai with the silver inlay---create question marks as to the tradition or school here. It really is a cool old tsuba, though... Steve

-

This tsuba is a bit of a stumper for me in terms of identifying a "school" or even the period it may have been made. In my experience, it is a very unusual piece. It is rather large and relatively thin, at 8.7cm x 3mm, and the concentric circle design/motif is one that I believe dates way back, even as early as Kamakura Period work. This tsuba is of course nowhere near that early, but I do wonder if it may be a late-Muromachi work. More conservatively, I would date it to Momoyama, if for no other reason than the comparative freedom and "wildness" of the design. The strait-laced conservative sensibility of the Edo period would seem to preclude this as a time of production, though earliest Edo is possible. The tsuba has lost most of its nunome inlay, as can be seen in the photos. I cannot make out the motifs of the inlaid areas exactly, but some appear to be characters. The plate is of iron, and an interesting detail is what appears to be very fine cross-hatching all over the central band of the plate, not merely where the inlay would have been. There is a very curious area around the seppa-dai, inlaid in silver I believe, though again, much of it has gone missing. The shape of this raised area is one I don't recall ever having seen before. The hitsu-ana are plugged, with lead? Pewter? Not sure about the material here... This is certainly not a tsuba you see everyday. It has good age and presence, and as I say, is an exceptionally uncommon design. Experienced collectors who have seen this piece have suggested that this is an early Satsuma guard, and is quite rare. More photos available on request. $450 plus any applicable paypal and shipping fees. Cheers, Steve

-

Death & Injuries In Samurai Battles

Steve Waszak replied to Gordon Sanders's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

"Was this plain stupidity or was it 'makin' a statement'? Not the knowledge of the fact that they would be heavily outnumbered, this was not much to be done about...But fighting in a 'traditional' way?" "The big shock/drama/lesson though, was not so much tactics and/or hardware per se, as the fact that an army of samurai--hereditary, professional fighters--could be beaten by one composed of conscripts. The whole episode was, in fact, essentially suicidal from the outset, and Saigo knew it." --Karl Friday I find it curious that Friday reaches the conclusion he does ("shock/drama") in the second quoted passage, given the observation he makes in the first ("...heavily outnumbered..."). A pack of hyenas can drive a lion from a kill, and even kill the lion. But one on one, the lion will kill, effortlessly, a hyena. Does the outcome of the Battle of Thermopylae mean that the Persians were stronger fighters (individually) than the Spartans? Hardly. What, exactly, were the numbers involved in Saigo's rebellion? By what ratio was his "army" outnumbered? Cheers, Steve P.S. I cannot make the shaded-quotes function work on my computer. Doesn't matter what I try, including checking the FAQs on quote insertion. -

In Kokubo Kenichi's "Ten Rules of Tsuba Collecting" (1972), he states the following: "Iron tsuba differ from other iron craft products in the sense that iron tsuba can be played with in one's hands. Even a rusty iron tsuba that defies the scrutiny of our eyes may have the right tactile qualities. Thus, revealing its potential. The touch and weight of a guard in one's hand is important in the appreciation and evaluation process. When making a tsuba, it is difficult to reach a good balance between the niku and the mimi. Therefore, if a tsuba feels good in one's hand, it usually is a good one (the balance of the thickness of the tsuba's center vs. the thickness of the mimi and the overall shape of the tsuba all play an important role here). Therefore, when enjoying an iron tsuba, we need to see with our hands as well as our eyes." I can personally attest to the value of being able to feel the texture of a steel tsuba, and so would agree with Kokubo's thoughts here... Steve

-

Michael, I am quite certain that Ford is well aware of Christian history in Japan. I think Ford's point had to do with the hopelessly sloppy critical thinking employed by some theorists/scholars in reaching the conclusions they do regarding the presence of Christian iconography in tsuba design. While there are some tsuba from the latter 16th century I am quite confident employ such iconography, far too many guards from this or later eras are interpreted to do so. Just as a quick example, I have a piece on the sales page currently (an Owari guard) which features a big, bold "cross" as its dominant design element/motif. Is this, then, a Christian tsuba? No, it isn't. I think what Ford is saying is that much too often, highly dubious conclusions are drawn, using even more dubious critical inquiry. Needless to say, I would agree. Cheers, Steve