-

Posts

3,091 -

Joined

-

Days Won

78

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Ford Hallam

-

Hi Brian why so suspicious? Omori Terumitsu, the 3rd generation master. My point being that if we were to line up a dozen or so tsuba by the first three generations I think the variations would become very clear. Here's a link to a papered 1st generation Omori Teruhide. As can easily be seen it's very different in style to this example by the 3rd master. As far as the actual layout or composition of this fairly classical wave design the only way to really study the differences would be to create line drawings of them. That way the layout can be seen and understood without distraction. Perhaps I should get my apprentice on the case....

-

I'll be the Devil's advocate here, as is my want Considering the various comments made about 'genuine Omori waves' it seems to me that a point that is very much applied in other areas of art appreciation is being overlooked in this case. The notion that the very first Omori wave tsuba was made and was in that first attempt simply perfect and the 'gold standard' by which all other thereafter must be judged seems counter intuitive. That there wasn't an ongoing development of technique, design evolution and refinement seems unlikely to me. In fact I would go so far as to suggest that if we can't see an evolution in a school's work then no matter how precise and exact the work is it is by definition mechanical in artistic terms. And that's exactly how a school's creativity dies out or becomes decadent. Without artistic inspiration and growth there's always a very real danger of work becoming overly elaborate and technical solely for the sake of showing off clever technique. " Never mind the artistry, or lack thereof, look at all the fine detail". But a careful examination of just those well known Omori pieces that have been published and can reasonably easily studied from photographs does in fact reveal a significant degree of variation in terms of composition and technique among the various masters of the school, yet we still hear a narrative that speaks of the school as being somehow a single entity in terms of output. This is simply too simplistic. I suppose what I'm getting at is that I don't think this topic has been comprehensively examined. As far as I'm aware there has been no real aesthetic study of the 'Omori wave' , no survey of all the supposedly authentic works nor any presentation of any sort of school development. This sort of investigation is standard practice in almost all other fields of art study. With much of tosogu study, though, we're still working with unexamined 'pearls of wisdom' that, with just a little investigation and analysis all too often appear to be unsubstantiated opinion or worse. With the previous in mind who made this? It is signed and papered.

-

Happy to help where I can, John Actually the punch is similar in general form to the one I used to create the fur on the Katsuhira's tiger utsushi in the film. There I deliberately kept the alignment constantly varying while moving in a general direction. To create the effect of uneven fur that was flowing over the cats body. In the case of the net effect the placement must be relatively exact. I'm presently carving some tiny mon menuki, while shuttling back and forth between my computer desk and my work bench behind me, so as I had some copper plate on hand to testing chisel effects as I work It was easy enough to test my idea as to how your tsuba was made. :-)

-

:-) From what I can make out (rubbish focus, John ) this pattern looks like it was made with a boat hull shaped punch. By interlocking the punch indents a sort of net effect has been created. I just did a little test with a similar punch to check that approach compared to chiselling it. Not every technique or application of a tool etc. has a label. And many used by the collecting fraternity today would be unknown to the Edo period makers. This pattern does look deliberately net-like. Probably 3 days to make, from a small cast ingot to finished tsuba. School? sorry, your guess is as good as mine :-)

-

I haven't had a chance to watch the film yet but will no doubt enjoy it in a moment. Cheers Gordon Just wanted to point out that this is gold leaf being made here the material we use in tosogu is far thicker and would be termed foil. The foil I use for nunome-zogan and occasionally on habaki is 0,025mm thick. That's about as thick as 80gram printer paper. The famous production centre for gold leaf in Japan is Kanazawa. The process is essentially the same though.

-

Cheers Henry, that was before my first cuppa this morning, and before the world 'out there' made me grumpy

-

Ok James, you got me :-) I actually wrote a little post yesterday but then questioned myself what the point was. I could give an opinion and say a little about why I think that way and all of that is obviously based on my experience and is naturally shaped by the values I find to be of interest in this subject. My value system, in this field, is merely my own idiosyncratic view of things. This tsuba might be your first, or one of your first, and you may feel that it is wonderful and mysterious, and for you, at this moment I imagine it really is. No doubt it gives you great pleasure, both thinking about it and the pure visual and tactile experience of looking and handling it. I can't put a value on that for you. I don't even know what you paid. Perhaps that sort of 'first love' is priceless. So with all that in mind it's tricky to offer an attempt at an objective assessment, and one that may be helpful beyond this piece. You have a genuine late Edo period tsuba. It's not the work of any of the main studios or followers of a Big name artist. Needless to say, and as you guessed, the mei is not genuine. It purports to be Tsuchiya Yasuchika, one of the Nara Sansaku. A REALLY big name. The fact that the mei is paced in that slightly unconventional position suggests that we're expected to think of the first master, the boss. There were 7 generations, in all, who used that name so some might suggest that maybe the mei indicates one of the 'lesser' Yasuchika. That might be a possiblity but I highly doubt it. Unless there is some real stylistic similarity with the work of any of the other generations that line of reasoning would merely be wishful thinking. Could it be some random other artist who signed with the same name? It's possible, but given the general quality and lack of artistic inspiration on show it'd be a bit like a very amateurish painter of holiday souvenirs signing his work Turner. He may really be called Mr Turner but he's not this one But to return to your tsuba and to use a genuine Yasuchika as a sort of bench mark against which to make some observations. For me one of the more salient features of Yasuchika's work is the way he finished his grounds. I don't just mean the area that might depict the ground the figures might be standing on in a composition but actually the whole of the metal surface. One story tells us he didn't have the money to pay a specialist to make the classic nanako surface that was required on court wear. I don't buy that story myself but it does suggest the old adage that 'necessity is the mother of invention'. And if a real artist has no choice but to be inventive, creative and expressive then Yasuchika demonstrates exactly that trait. Chances are that any tsuba considered to be a genuine Yasuchika will have a subtly modelled or textured surface quality quite unlike any other, even among his own works. He kept evolving his finish throughout his life. On your little tsuba the surface is the most basic and quick finish a metalworker can actually apply. This is another striking Yasuchika, one of my favourites just on the basis of the ground treatment. It's utterly confidant and may be unique. I don't need to say too much about the workmanship in your tsuba but let's have a brief look at the inlay work and compare it to that on my second example. Notice how the inlay in yours looks as though it's simply stuck on the plate and how it all looks a little hard edged. It's well enough defined that we can recognise all the elements but they lack any sense of depth or weight. They're merely motifs, badges, if you like. On Yasuchika's piece the elements, while clearly distinct and recognisable, also have an subtle abstract quality to them. We can see clearly what the elements are but they have so much more subtlety to savour in the way the forms are modelled. The fine textures on the metal surface act like shading and enhance the feeling of depth, weight and colour tone. This is 'painting' with metal. While we're here notice what Yasuchika did. See that expressive ground? How it looks as though it was almost just hewn with an adze. (I recently bought an adze for wood work so I'm all over that sort of thing at the moment ) He wasn't messing about, he created a surface that speaks directly of the energy and vigour he applied in carving it. There can be no hesitation nor wavering when carving a surface like this. Any attempt to 'fake' it will immediately appear weak and unsure. And on that almost rough 'canvas' he ever so sensitively arranges the elements of this composition. Sit back and consider how easy each element appears to be settled into the ground. How each leaf, the dried fish, chestnuts, those tiny gold twigs and berries...how each is simply in the right resting place and how it all ties together in a dynamic arrangement that, while a still-life, is not at all lifeless or static. See how the arrangement draws your eyes back and forth from one part to another, and back again...and then oh, that delicious bit there... Michelin star chefs might do well to study work like this to give them ideas on how to artistically plate up their fancy food Enjoy your tsuba for what it is. It's a perfectly honest piece of basic craft work. The mei is a later addition I think, add with the intent to convince, or deceive, a tourist with only a little guide book with a few names of great Japanese artists as guidance. But while exploring your tsuba try and bear in mind this little peek we've just shared of the masters approach to his art. I hope this helps a little bit.

-

Hi Barry, having a device on hand at a shinsa is something we have already discussed here in Europe. I'm working on it. :-) Curran, sahari has been investigated. I have the metallurgy pretty well covered now. In fact sahari has a much older history than the Hazama and Kunitomo groups but it appears in the historical record somewhat differently. It's a bit complicated to explain in a forum post (it's a chapter in my book) but the alloy itself goes back more than 2000 years and was in this instance a Korean invention. The trick is in how it was heat treated. With respect to analysis data being used to authenticate works, we'd need to sit down with a good spread of pieces to establish a useful data set. A 50 sample survey could be done, at an event almost anywhere were the pieces made available, in an afternoon.

-

Hi Franco I found one group of a very particular, perhaps unique, brass alloy used by both Mitsuoki Otsuki and his son. This in itself is very suggestive but would only become more reliable with more data. Similarly the 'so called' sentoku used by Mitsuhiro, he of the 1000 monkeys etc. has been shown to be essentially the same alloy (again pretty distinctive/unique) in a number of pieces by him/them I and II. Patterns are emerging in the shibuichi group that may allow for a degree of dating to be established. But beyond this we really need a much broader data set. For example there may be consistent variations in varieties of shakudo from different centres of production but without lots of analyses of work from Edo, Kyoto and perhaps Osaka I don't have enough to see patterns as yet. I'm fairly confidant these patterns will emerge as we build up the data set because already I'm seeing a much greater degree of variation and distinction than we previously imagined. It may be as varied as paint colour mixtures used by different painters in the Renaissance.

-

Curran, John yes, the technology has advanced rapidly in the past 15 or so years. The device I've been using looks a bit like a bar-code scanner you'd see in a supermarket. It's completely non-destructive, penetrates though surface patina and corrosion and delivers results up to 3 decimal points in under 30 seconds. The only drawback at present is the cost of buying the kit, I've been supported on a few surveys thus far by the agents here in the UK. I'll be discussing this survey idea with the Ashmolean, in Oxford, in the new year and I've had discussions with the MFA previously. What the basic analyses have already revealed is that the range of alloys is far greater than previously documented or imagined. The real work, though, is trying to understand what all the numbers actually mean. What does the inevitable trace of lead in copper tell us, the arsenic that crops up in certain alloys but not others, and tiny traces of gold in silver and shibuichi? Which bits are deliberate, which where unknown to the makers, how do alloys change over time and what of remelting alloys? There are many such issues that must all be factored in to the interpretation of the data. And then these analyses must be anchored somehow in the historical record. By which I mean we need to try and fit individual analyses results in to a time-frame. This context, using dated pieces and the working lives of the artists who made authenticated pieces, may then help to establish some sort of chronology of alloys and metals in the Japanese metalworking tradition. I hope to be publishing the results of my investigations very soon

-

Cheers George, yes , the mei is somewhat dodgy but I thought it'd be a fun exercise for some :-) The work on the front is more reminiscent of Joi and is actually rather good in hand. Hi Curran, just working with a relatively limited amount of data I've thus far amassed it's starting to yield a remarkable amount of usable information. It's early days yet but I think this analytical approach to the subject may well eventually rewrite much of our 'accepted wisdom'. Certainly the probability of there being school or even studio specific alloy compositions already seems to be hinted at. And with a broad enough survey issues of gimei may eventually resolve themselves where analyses reveal the pretenders.

-

This is a kozuka that is housed in the V&A repository in London. Catalogue number: M.1259-1931 In March of this year it was part of a fairly large materials analysis survey I carried out as part of my on-going research into the history of these curious Japanese alloys. This is in fact the first documented and positively identified example of Kuro-shibuichi, black-shibuichi. You saw it here first. There are a few recipes given in early 20th century texts for making this alloy. These compositions are what subsequently appear in modern Japanese publications. The problem I've had is that I've not yet been able to find any Edo period examples that match these particular compositions, which are given as ratios of shakudo and shibuichi. This piece, with a mei purporting to be that of Yokoya Sōmin, has a composition that very closely matches a composition given by the Imperial artist Unno Bisei II ( 1864-1919. and from Mito) He advises shakudo in 10 parts and silver in 3 to 4 parts. There's obviously room for some variation here as the shakudo alloy's gold content is not specified but a narrow range of possible compositions can be estimated quite easily based on typical shakudo alloys of the period. and the mei. Apologies for the poor images, it was a long day. Anyway, this is just a little something I was working on this morning and thought might be of interest to board members. Any thoughts on the mei would be welcome. kind regards to all Ford

-

As a craftsman, artist and sometimes restorer I would, in this case, leave this tsuba as it is. From my perspective restoration needs to be a very careful balance between a piece being helped to look like a reasonable example of its type and of its age and, on the other hand, the natural urge to 'improve' the appearance based on personal preference and possible commercial advantage. With this particular piece the surface appearance, while in no way reflective of what it once was, is now a testament to it's age and is, as a bonus, quite satisfying from an aesthetic point of view. Just to be clear, this appearance can now in no way be assumed to be part of it's supposed Japanese or samurai history, so much as happened to the original patina, if any actual traces remain. Having said that it is apparently an old bit of pleasingly shaped brass that has a satisfying patina. It is what is appears to be, no more and no less. I appreciate it for that and need to imagine nothing more.

-

Brian, we know essentially very little about how early metalworkers actually worked. The few Edo period documents that discuss metalwork are silent on the issue of magnification. All we can really do is look at the objects themselves and try to imagine how, given available technologies, they might have been made. Fine work in metal is particularly tricky because when carving the chisels inevitably leave the cut metal mirror like which further complicates seeing things clearly. I would suggest, also, that particularly when lenses first started to be used, that their use wasn't advertised. Having a serious advantage over one's competitors would not be something you'd want them to know about. You'd just want to leave them wondering in amazement at how you managed to 'suddenly' start make so much finer work than the rest of the optically challenged chisellers. But as has been pointed out on this thread lenses were known and used in the Edo period, this is clear, the question now becomes, when did they start using them? For me it's a matter of looking at the work and trying to judge whether or not it could be done without magnification. As I wrote earlier, lenses are known to have been brought in to Japan from the mid 16th cent. 1550's onwards. Local craft skills would have quickly allowed for the manufacture of lenses in Japan thereafter. The links Franco posted provide some solid evidence of that I think.

-

The ancient Greek, Romans and Egyptians all had a reasonably good grasp of optics and were very capable of grinding lenses. There even exists a lens shaped from emerald that was thought to had belonged to the Emperor Nero. It is shaped to fit the eye socket and further shaped to correct an astigmatism. Perfectly polished rock crystal spheres are to be found in the Shosoin Repository that date back to the 7th century and we know Portuguese traders imported magnifying lenses into Japan from around the second half of the 16th century. The point being, if you can't see it you can't carve it While some 'authorities' sniff at this book I found it very interesting and much of it quite credible. The author tends to wander off into some dodgy theories in his other books apparently, I haven't read any of them.

-

Hi James I think this is quite a pleasing little piece. It's not in the best of conditions but the workmanship, while not exceptional, is more than adequate. It's very hard to be specific in terms of school with pieces like this as similar pieces can be found in a number of different schools. Having said that the cloud pattern in gold nunome-zogan on the edge is distinctive. The cloud pattern itself is not uncommon but this version might be recognisable on other signed pieces. Some digging might be required. To my eyes the clouds look like those done by the Meiji period Komai company, who were based in Kyoto. The tsuba is earlier though. Similarly the way the waves are carved is also distinctive. Obviously we can point to loads of tsuba with what look like similar waves but look more carefully and perhaps you'll notice variations, a bit like the way handwriting can vary. I couldn't say for certain off the top of my head but I'm thinking Tetsugendo school, they were based in Kyoto.

-

Hi Gethin you might make a reasonable start by supporting Markus Sesko's work His translation of the Akasaka Tanko Roku makes for interesting reading and is very inexpensive.

-

Hello Michael, and welcome to the forum. It looks like a bamboo grove and some sparrows (?, I'm no ornithologists but then again neither was the maker of these ) and a hut. Having said that they look very much like modern amateur work as the actual design/composition seems to me to be completely uninformed with regard to genuine Japanese artistic genres. The carving and finishing technique also looks fairly unrefined and naive. Add to that what looks like amateur re-wrap of the actual handle, the wrap is wider than the fuchi for starters and that first cross-over is pretty ropey, and I think we're looking at a well meaning attempt to restore or complete and older koshirae.

-

My memory fails me at the moment but the pairing of nata and plum branch is an allusion to a poem or scene in an ancient tale. It'll come to me eventually....but there is a very clear literary signal in the design.

-

-

Not in the Shinsen Kinko Meikan, the Toso Kinko Meishu Roku nor Haynes. And while the image is slightly pixelated I also think it may be modern cast piece.

-

And the mei is on the wrong side of the seppa-dai or signed on the reverse.

-

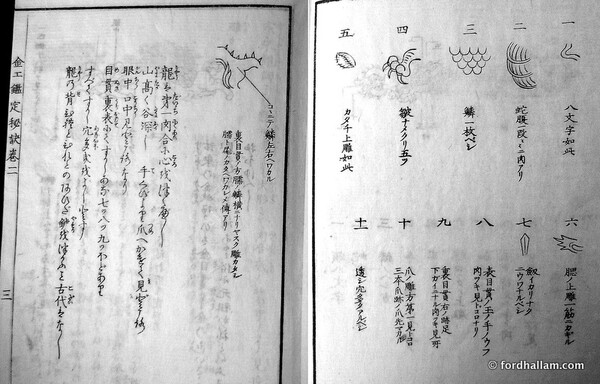

The most obvious problem for kantei points on tosogu is that if they can be readily described they can then reasonably easily be replicated. In fact, for fakers, they'd be quite handy. The maxim of the art forger is, 'give them what they expect'. Just for interests sake here are two pages from the Kinko Kantei Hiketsu, 1820, "Secrets in examining metalwork. A guide to the detection of forgeries in the metalwork of the Goto school." (2 volumes) And this was no private or limited edition printing. Back in the day, books like this, that purported to educate the masses in all aspects of the arts, were hugely popular and common in the major cities of Edo Japan from the start of the 18th century. I imagine they were to be found in most metalwork studios of the period too. For anyone interested in this publishing phenomenon I'd recommend 'Edo Culture, Daily Life and Diversions in Urban Japan, 1600-1868.' by Nishiyama Matsunosuke.

-

I would hope not. Can anyone imagine something similar for any non-Japanese artist of the last 1000 years? In terms of artistic connoisseurship the very idea of 'kantei' is the very lowest level of tosogu appraisal and appreciation. It's in reality merely a very limited and constrained judgement based on arbitrary and unsubstantiated subjective criteria. Until Japanese authorities provide explanations, rationale and evidence for their pronouncements I fear that in terms of general academic consensus their 'labels' lack any real credibility.