-

Posts

4,283 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

96

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by SteveM

-

Signed Naval sword with surrender tag, rust removal?

SteveM replied to phil reid's topic in Military Swords of Japan

Looks to me like 関住服部正廣作 Seki-jū Hattori Masahiro saku = Made by Masahiro Hattori of Seki (province) On the wooden tag it says 左舷 sagen (port, as in left side of ship...I'm not sure what this is doing on this tag) 佐々木平 SASAKI Taira (Japanese name) 一曹 Issō (petty officer) -

Congratulations on a successful transition. So far so good!

-

Translation assistance on good luck flag

SteveM replied to ww2colorado's topic in Translation Assistance

Possible to post a bigger picture of the flag? Or, higher resolution? -

Hello, not a mei, but a random and (probably) fraudulent name intending to make the sword look like a legitimate Japanese sword. 田中正夫 Tanaka Masao Every bit as common a name as, say, John Smith.

-

Help for Someone with an RJT blade

SteveM replied to Bruce Pennington's topic in Translation Assistance

Putting as a spoiler for those who want to try -

Andrew, thank you for posting that wonderful letter from a most historic moment in time. For me, the story of the sword's acquisition is a million times more fascinating and charming than the original tall tale, and much more precious because your grandfather documented it so eloquently. Coming from the Bay Area myself, I felt a connection hearing him describe the Imperial Palace grounds as being comparable to Golden Gate park. And how funny to hear him initially lament that other soldiers had shinier, newer-looking swords, and that his own looked like a dull "toad-stabber", when in reality the shiny stuff tends to be junk. Interesting also the time of the letter, just months after the end of the war. We get a sense of how close to starvation the country was, when your grandfather describes the scarcity of food in Tokyo. How fascinating it must have been to browse the black markets of Tokyo then. You have a true samurai sword, whose reputation is, in my opinion, enhanced by the letter.

-

Help with Kinpun-Mei, possibly Hon'ami?

SteveM replied to Ronin 47's topic in Translation Assistance

From Darcy Brockbank's site https://blog.yuhindo.com/honami-origami-and-valuations/ The earliest Honami judge that we commonly encounter is Honami Kotoku who worked for Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu. He was the 9th master of the Honami family and is held in very high regard. He did not leave many origami behind but he left gold inscriptions in the nakago of blades he judged. -

松楽造 Shōraku zō 黒楽茶碗 Kuro raku chawan 赤楽茶碗 Aka raku chawan 一対 Ittsui 前大徳香林 Zendaitoku Kōrin Pair of black and red tea bowls made at Shōraku kiln Zendaitoku Kōrin

-

濃州住木村祐正作 Nōshū-jū Kimura Sukemasa saku Made by Sukemasa Kimura, of Nōshū province

-

-

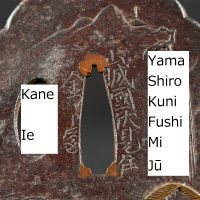

The darker tsuba (the one on the right in the picture showing both) seems to be 山城国住 金家 Yamashiro kuni-jū Kaneie The other one is 正阿弥 Shōami

-

Help With Miyaguchi/ikkansai Kunimori Please

SteveM replied to Navymate's topic in Military Swords of Japan

Here is a NBTHK Hozon paper for a Kunimori sword. The sword is dated 1944. The paper is dated February, 2020. -

I agree, its not a very convincing 峰. I am open to other alternatives, but considering the artist and the seal...I don't know what else it could be.

-

萩焼 茶盌 正峰造 Hagiyaki Chawan Seihou tzukuru (zō)

-

I thought it was gibberish too, but it seems to be trying to say 大九号四 (My guess; somebody attempted to write 第九四号, meaning #94 or presumably "Type 94", as in the sword type) 別?病院 (betsu? byōin - hospital) Hard to tell if it is something a westerner wrote, trying to mimic Japanese characters. Or maybe it was written by someone with terrible writing skills. The three characters at the end look like 十永三 (jū naga san) but I'm buggered if I know what it means. Part of an address, as Robert says, or a name?

-

Looking for advice on this wakizashi

SteveM replied to Jamesu's topic in Auctions and Online Sales or Sellers

Hard to say about the price. I do think the person is asking for a price that is at the very high end for this ensemble. The generation is sometimes listed on the authentication papers. If the sword has the characteristics of a certain generation of swordsmith, and the authentication team feels the sword is representative of that smith, they will attribute it to that specific smith. I don't have any statistics on how often this is. Its not unusual. And its also not unusual for them to just throw it in a generic box (say, Yasuhiro) and decline to pinpoint it to a specific generation. Regarding the size, as I said there is a wide range of thoughts on this. I wouldn't say for sure that there are children's swords passing for wakizashi. When there has been a sword of this size that somehow looks like a miniature katana rather than a wakizashi, there has been speculation on the forum about what the nature of the sword is. The bling on this particular scabbard tells me this scabbard wasn't meant for war or for official duties. Edit: I agree with what Robert says about the pricing. -

Hello Nick, It looks like the signature reads 吉近作 Yoshichika saku (made by Yoshichika) Usually you will find an arsenal stamp, struck on the sword above the mekugi-ana (a.k.a. the holes for the pegs). The pictures you posted are just far enough to make this section a bit hard to see, but if you can find such a stamp on your sword it means the sword was produced in a Japanese arsenal during the war. If you cannot find a stamp, you start to go down the rabbit hole of trying to find out exactly who made the sword, when it was made, and who it was made for. There was a ww2 smith who made swords, or at least supervised sword production, using the name Yoshichika (spelled exactly the same way that is on this sword). I'm inclined to think this was one of his swords. However the hamon (temper pattern) on your sword is very atypical of WW2 swords. It looks somehow artificial. And the signature doesn't match the signatures found on the wartime Yoshichika's swords. The two holes on the tang are also a slight anomaly, indicating perhaps that someone had to put a new hole in the tang in order to accommodate a new handle (tsuka) because the hole in the new tsuka wasn't aligned with the existing hole in the tang. This kind of adjustment is super common in old swords, but you don't see it so much on wartime swords since they were more or less mass-produced in an assembly-line type of operation, with scabbard makers working closely with the sword makers, and the various parts being numbered for assembly. The top hole would have been the original peg-hole, and the bottom one (that has obscured the smith's name) is the later addition. There could be an arsenal stamp hiding under the removable collar on the blade (habaki). Some pictures of that area might help. Some better pictures of the tip might help. But your sword looks like it has had an amateur polish, which tends to ruin the features in the steel that are interesting for sword collectors. It could also be the thing that is causing the hamon to look artificial. Sorry to lead you to the edge of the rabbit hole. That's all I've got for now. The militaria guys can add more, hopefully. The scabbard looks OK to me. Actually it looks to be in excellent condition. The sword... I would like to see more. Could be an unusual WW2 sword, could be a very well-made fake.

-

Looking for advice on this wakizashi

SteveM replied to Jamesu's topic in Auctions and Online Sales or Sellers

The NBTHK paper is from 1977, and simply claims it is a mumei wakizashi attributed to Yasuhiro. It doesn't say which generation. Its a very unusual, flamboyant koshirae. To me, looking at the size and the koshirae, it feels like its one of those pieces that was made deliberately small, almost like a miniature sword - for purposes that is the topic of debate here on NMB. Sword for a minor? Children's day sword? Prop in a play? Or just a regular wakizashi that happens to have a very glam koshirae? I don't hate it, but if I were starting out my sword collection I might try for a more orthodox piece with recent papers. This one feels like a curiosity. It feels like the koshirae is the draw here, rather than the sword. oops: and also, go to your profile and add your name so we know what to call you. -

英満 Omori Terumitsu is another possibility, given the similarity in 満 and the kanji that looks like 兩. But that leaves all the other bits unaccounted for. (And there is no sanzui-hen...obviously) I do think its trying to be Teru-somebody from the Omori school.

-

篠田氏房 Shinoda Ujifusa WW2 swordsmith