JohnTo

Gold Tier-

Posts

284 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

1

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by JohnTo

-

This was one of my first serious tsuba purchases (RB Caldwell collection, 1994), a tosho tsuba that typified 'bones' to me at the time. It still provides a pleasurable sensation if I run my finger over it. I can understand why the Japanese find it so exciting. Interestingly the tekkotsu is only at the top and bottom of the tsuba. I assume that it must have something to do with the way that the iron was folded and the bones squeezed out during forging. Best regards, John

-

Hi Guys, Grev asked for examples of non ferrous Nanban tsuba. Here is one, together with an almost identical one in iron. Both have animal/demon masks at the top and bottom (the iron one has them at the sides as well) and have dragons in the side panels. The brass tsuba has pearls in inome bori (boar’s eye, heart shapes) piercings at the side. The iron tsuba has some gold nunome and the rim of the brass tsuba may have traces of gilding. The brass tsuba has copper seki gane in the nagako ana, indicating that it was mounted, and a shakudo plug in one of the ryu hitsu (must have been quite an effort to have shaped that!). The Compton Collection had a similar brass tsuba (Part I, lot 100) which was described as a Canton tsuba from ca. 1600, with no ryu hitsu. Reading between the lines from various sources (I don’t have hard evidence) it would appear that this style of Nanban tsuba originated in China (Canton) and was exported to Nagasaki, along with Chinese craftsmen who set up shop there. From there they migrated into the adjoining Hizen area where the tsuba became more Japanese (e.g. nagako ana lost the square shape of these examples) and possibly kicked started the Hizen style sukashi (100 monkeys, etc). Best regards, John (just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

There is a similar iron tsuba in Greville Cooke's Birmingham Tsuba Collection, page 26 (col no 1930M893), size 78mmx78mmx41 mm. This tsuba has five leaf bamboo sprigs (kamon?) in the lattice and is described as Choshu, ca.1700, which I suppose covers a lot of artists and sub-schools. Nice tsuba by the way. Don't forget to add the metal in the description, which I assume is iron. Best regards, John

-

I’d like to present this tosho tsuba for comments. It is a small (7.0 cm height, 7.0 cm width, 0.3cm thick), sukashi tsuba, probably depicting a flower with six petals, the centre of each being removed. The piercings on one of the middle petals has been widened (maybe at a later date), presumably to accommodate a kodzuka. The plate is flat and slightly pitted, I think after burning in a forge rather than rusting (pitting is too even and lack rust scabs), or hammering (indentations look too small) and has a black (rather than brown) patina, worn in places to show the bare iron. The seppa dai is a long oval shape and the nagako ana looks too long in relation to the size of the tsuba. The size of the nagako ana relative to the tsuba looks wrong for a katana, perhaps it was used with a wide bladed tanto. There are three areas of shallow punch marks around the nagako ana rather than the heavy bashing seen on many early tsuba. The initial impression that this tsuba gives is one of something that a village blacksmith knocked out during his lunch break, anytime during the past 150-450 years and it has little artistic merit. However, there are a couple of features that may give it some historical value. Firstly, looking at the edges of the piercings there are signs of delamination of the iron showing it was possibly fold forged or welded from iron plates of different hardness. Secondly, there is the provenance. This tsuba was bought as part of a bag of 19 loose tsuba of mixed quality (all rattling together in the auction. Ugh!), being part of the remnants of the stock of an oriental antique dealer who died 30 years ago (Albert Newall, 1920-1989). There also appears to be traces of an old collectors number (70) on the seppa dai. So, it looks like at least two previous western collectors attached some value to this tsuba. I have only found a couple of tsuba with similar designs. The Church Collection at the Ashmolean museum (EAX.10010) tsuba has a similar 6 petal design, but the edges are rounded, ryu hitsu have been incorporated, the tsuba is much bigger (9 cm) and described as Heianjo, 17th C. The British Museum have one with six cherry blossom shaped petals (1613-93, illustrated in their Swords of the Samurai catalogue, plate 96) also forged with rounded edges and attributed to Nishigaki Kanshiro. My tsuba is crude in comparison with these. Best regards, John (just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

I recently bought this odd ‘tsuba’ along with 19 regular tsuba in a job lot at a local auction. It is quite large (8.4 cm dia, 0.4 cm thick) and appears to be cast brass. The subject looks like a cross between a fish and minogame turtle. The more observant NMB members may notice that something seems to be missing, but I’m sure that a bit of work with a drill, hacksaw and file would soon remedy this. I have no idea what it actually is, but perhaps it is stretching things a bit too far to suggest it is a tsuba blank and the Japanese tsubako would have cut a ‘made to measure’ nagako ana for his samurai client. You thoughts will be appreciated. Happy New Year, John (just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

Hi Ruben, Sorry for being so tardy, I've had other things than tsuba and Old Pec to attend to. Thanks for the pic of your tsuba. I like to copy tsuba with similar signatures and put them in my research notes. Masa was the first kanji I learnt about 60 years ago, just in case I found a Masamune blade in a junk shop. I did not want to miss it. Back in those days, even as a kid, we would not consider buying a blade without a signature, but never found a Masamune. Marcus Sesko lists nearly 30 'Masa' tsubako in the Bushu Ito school, so, yes, a common kanji. Yep, I did note that the badge on the Old Pec was etched, like my tsuba. It is not so apparent on the bottles and that is a far as I usually get. A word of warning. One pint of Old Pec @5.6% enhances the appreciation of iron tsuba, two diminishes it. Old Pec and katana viewing should never be mixed. Best regards, John

-

Thanks Kyle, Your photo of the Asmolean tsuba is much better than their on-line version. I would say that the signature and kakihan are identical to mine, as is everything else about the two tsuba. So they were probably made in the same workshop, by the same hand, though probably not Goto Renjo. Thats the great thing about NMB, there is often someone out there with the info that you want. Regards, John

-

Richard, very good pics. It is easy to see that the mon inserts and the surrounding brass rings are one piece. In my example, shown previously, the mon are separate from the brass rings, just ahmmered into place. Best regards, John

-

Pete. Thanks for the reference, I don't have it, but luckily you do. One thing puzzles me about the number of gimei in the Edo period and that is how did they become so numerous in what was effectively a police state? As I understand it, the Togugawa Shogunate kept a pretty tight contol on everything, for example the kabuki and ukiyo-e print makers were subject to strict censorship. How come those involved in making swords and kodogu were making so many forgeries? For example, I hate to think how many examples of waves inscribed Omori Teruhide I have come accross. It makes me think that officials, maybe even the local daimyo, were taking bribes and turning a blind eye to the number of forgeries being produced in their locale. Best regards, John

-

Ruben, Old Pec' and tsuba are a great combination. I forgot to add a special thanks for the info regarding the unusual 'fu' in Efu. Alway good to learn something new. Best wishes, John

-

thanks Ruben, Steve. Ruben, 'Enjoy?' Don't worry I will. Its Friday afternoon and I have a pint of Old Peculiar waiting for me, which will help me hear the iron of this (and other tsuba) speaking to me. Best regards, John

-

The good thing about finding a signature of a minor artist on a piece of kodugu is that it is probably genuine. As the fame of the artist increases, so do the number of copies, fakes, homages and utsushi. I have a few iron Nobuie and Kaneie tsuba with passable signatures, but look as if they were made yesterday! The tsuba that I am presenting today for comment is from a bag of 19 loose tsuba, one of about 100 items that represented the remnants of the stock of the a Cape Town Oriental art dealer who died about 30 years ago. The items had remained in boxes until a recent auction. This oval shibuichi tsuba is decorated with a shippo (七宝, literally seven treasures) design, and referred to as a shippo tsunagi (shippo chain) when the inner and outer circles are interlinked, as this example. The symbol is found in ancient Egypt as well as Asia and is at least 3,500 years old and embodies a wish for family happiness and financial success. The design is finely cut with smooth even lines with the major open areas between the circles all cut to the same depth. The evenness of the cutting is so skilful that it looks as if the pattern were made by a machine, rather than by hand. The tsuba has a single kodzuka hitsu and both the size and overall design indicates that it was made for a wakizashi rather than a katana. There appears to be some wear on the seppa dai, but the nagako ana looks pristine as this tsuba was probably tailor made for the sword and thus did not require seki gane or punch closure of the nagako ana to obtain a precise fit. The tsuba bears the signature of Goto Mitsunobu/Mitsutoshi (後藤光寿) with a kakihan. According to some web pages, Fukushi reads the signature as Mitsunobu and the Toso Kodogu Koza says that although the kanji are commonly read as Mitsutoshi, Goto documents list the artist as Mitsunobu, with furigana reading aides by his name. As the Goto family read his name as Mitsunobu, it would seem that Mitsutoshi may be a modern mistake which has been repeated enough as to cause confusion. Goto Mitsunobu was possibly the third son of Senjo and adopted by Renjo (10th generation master of Goto Shirobei line of family) after the death of Renjo’s son, Mitsuyoshi, aged 25. Mitsunobu married Renjo’s daughter (probably a good career move) and became head of the Goto school aged 34. Mitsunobu became Tsujo (11th generation master, 1663-1721) and lived in Edo. The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford has a virtually identical tsuba to this in the AH Church Collection (Accession number EAX. 10899 with collectors number 1158, see pic). Some of the detail (especially the signature) is difficult to see in the Church example, but the distribution of the circles is the same, as is the placing of the signature. Only the karahana (four pettalled flowers in the centre of the circles) look slightly different, and are more like four dots in my example (a different punch was evidently used). As far as can be seen from the Church collection photo, the kakihan appears the same, but the rest of the signature lacks clarity for a critical comparison. However, the signature on the tsuba in the Church collection is probably misread and is listed as being signed by Goto Mitsunaga. It is also stated as probably not by Tsujo, the XIth master. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts has another identical example (accession number: 11.5433) signed ‘Goto Mitsutoshi’ (see pic). This has the same karahana, as the Church example, and the two look as if they could have been turned out together from a 3-D printer. The ‘Toshi/Nobu’ kanji differs from mine in that it appears stiffer and the lower half has a square rather than a single stroke. The three tsuba are so similar that I would say that they came from the same workshop and perhaps from the same hand (though probably not Tsujo’s). One source reports that 24 items by Tsujo have passed Juyo, so I suspect that there are more utsushi extant than genuine works. The difference in the second kanji of his name is interesting. Perhaps Tsujo was called Mitsutoshi and Mitsunobu, slightly changing the kanji when he changed his name. Unlikely, but I like to think outside the box. Whether genuine or fake I think that it is a skilfully made tsuba and I wish to treat it with care. Close examination of the piercings reveals some dirt and crud. What is the best way to remove this without affecting the patina? Washing with a water based detergent, spraying with an aerosol electrical contact cleaner (alcohol based, no chlorinated material), or soak in white spirit to remove grease? Dimensions: Height: 7.05 cm, Width: 6.65 cm, Thickness (rim): 0.35 cm Thanks in advance for any help. John (just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

I’m having trouble reading the last kanji of this signature, which I believe reads Efu ju Masa????. The last character just looks like a squiggle to me. This oval iron tsuba is unusual in that it is a flat plate and the decoration appears to have been made by etching. At first sight the brown patina of the iron appears to be bronze, but it is magnetic. The scenes on the front and back are similar and consist of a range of three mountains at the top, a woodland in the middle (with maybe a thatched hut) and a lake or riverbank at the bottom, one side with a man in a small boat, the other with figure looking over the water. Height: 7.1 cm; Width: 6.7 cm; Thickness (rim): 0.15 cm, Seppa Dai: 0.4 Any other information regarding the maker would be welcome. Best regards, John

-

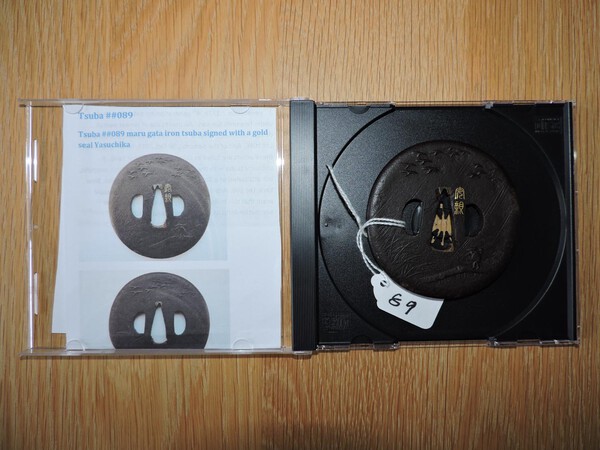

The trouble with standard wood tsuba boxes are that they are quite large. I have about 10 and I'm short of storage space. I took delivery of 25 slimline tsuba boxes yesterday, cost less than 50p each. I do need to fit linings in them and have not quite worked out the best way of doing that, but as the topic is 'hot', I will probably cut out CD shaped liners and then cut out a profile of the tsuba. I thought that I should write now and share my initial experiences. My tsuba boxes look remarkably like CD jewel boxes, which is what they are (make sure you get the 10 mm wide ones and not the thin ones). I intend to put copies of my write ups of the tsuba in each case, just like the sleve notes of a music CD (I quickly printed out a rough version just to illustrate). Just knock out some of the central spines to hold the CD and the tsuba is held in place. And I already have a storage unit, just needed to through out some old CDs. OK, not as elegant as the wood boxes, but a lot cheaper! best regards, John

-

I really hadn’t given much thought to the kashira as, without the fuchi, it’s a bit like having just one sock; OK if you are a one legged man, but otherwise… I guess I will have to start searching Ebay. Christian, I’m not sure I understand what you mean by ‘definitely- NO Yagyu!’. If you read the original posting carefully you will note that I did say that I did not believe that it was Yagyu work; just based upon a Yagyu design. Sasano wrtites that Inaba Tsuryu published an illustrated album of 110 Yagyu designs and that Imaizumi Gennai compiled an album of 163 Yagyu designs. Unfortunately, I do not have reference to these works, but perhaps you did and failed to find this particular design? Yagyu designs were apparently used by tsubako from other schools including the Ono, Owari and Bushu, right up to the haitto-rei, according to my sources. That does not mean they were copied skilfully or with all the characteristics associated with Yagyu work. I still propose that this tsuba was based upon a Yagyu design and to support my supposition I attach a couple of pics of Yagyu tsuba that I found on this site, together with a NTHK certificated Ono tsuba that Grey Doffin had for sale. The Ono tsuba was stated as being based on a Yagyu design and is effectively 2-D like mine, i.e. flat and not sculpted. Both the Yagyu tsuba have waves and the mysterious circular hole in the design, like mine, which I still would like to know what they represent. I rest my case for the defence. As a relative newby to tsuba collecting I like to glean as much info as I can for each new addition to my collection and appreciate constructive criticism to my observations. Best regards, John (just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

When I bought this tsuba it had a copper crayfish kashira riveted to the seppa dai (see pic). Luckily it was only lightly attached and not hard soldered on and I was able to easily remove it. Possibly it was used as a paper weight and the kashira was used to pick it up. The tsuba itself was in good condition apart from some red surface rust (I understand it had been stored for 30 years in a loft or basement0, which I removed with WD-40, cotton buds and wooden cocktail sticks. The iron has a matt black patina and appears covered with speckles, see pic of rim, indicating that the iron was forged from a mixture of irons and not fully homogenized to a lifeless plate. The tsuba is what I call ‘2-D sukashi’, in that the plate is flat and the design cut vertically through the iron with no attempt to round the edges or sink the body below the rim. The design appears to be a tomoe (comma) with a long tapering tail, which forms the rim. Waves are shown rising out of the rim, possibly crashing against the body of the tomoe (duplicating as a boulder?). Overall, the design seems to shout Yagyu, but waves in Yagyu designs are generally rounded at the edges giving a softer 3-D look and I understand that layering of the iron can also be seen (I can’t see any here). I would therefore think that this is a copy of a Yagyu design. I read that Ono and others copied Yagyu designs, but the examples that I have seen illustrated also have some 3-D characteristics. I have also noticed in some illustrations of Yagyu tsuba the presence of a small open circle in the design, which this tsuba has in the top left corner between the wave and the rim. Any idea of the significance of these? The presence of two small (1 mm diameter) holes at each end of the seppa dai have, no doubt, reduced the value of this tsuba (not that I intend to sell it). But by how much when one considers the heaving bashing with hammer and chisel around the nagako ana that it received in antiquity? So there we have it, a sukashi tsuba with what I think is a Yagyu look. Comments and opinions would be welcome. Height: 7.8 cm, Width: 7.7 cm, Thickness (rim): 0.45 cm Thanks John (just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

Thanks Steven and Steve When I read the first reply I was a bit dubious of the first kanji being ‘yasu’ (安) as it looked nothing like my ‘yasu’. Searching on the web I found a couple of tsuba (pics attached) which were sold at Bonhams. Tsuba 1: Nara Yasuchika II is a similar style to mine, iron carved with chidori, but the signature is安親.Lot 1086, Arts of the Samurai, 08 Oct 2013, New York. Tsuba 2: A shibuichi tsuba with an with an elephant and sparrows in takabori, shishiai-bori, and copper and gold takazogan. Apparently the tsuba was made to deliberately look worn with age. The signature on this is康親 in a seal, with the two kanji looking like mine. The tsuba was actually catalogued as Shonai, after Yasuchika. Lot 306, Arts of the Samurai, 30 Oct 2017, New York. So I guess that’s it. Yasuchika. Which just leaves the question ‘Is it genuine?’ Always a problem Thanks again, help from guys like you is what makes NMB so great. John (just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

Hi guys, Can you help with the gold inlaid signature on this iron tsuba? The signature is not in a seal, but the cursive (correct term?) style of writing has me lost with the first character. It is a bit like Kaze/fu but I don’t think so. The second kanji appears to be ‘chika’ A description of the tsuba is as follows, and my best guess as to school would be Kaneie. A maru gata iron tsuba with a black patina, slightly dished with rounded edges and the usual pair of kogai and kodzuka hitsu (the kodzuka hitsu is lined on the straight edge with apiece of shakudo). The nagako ana is rather wide and is fitted with copper seki gane to top and bottom. The tsuba has a simple design, carved in shallow relief (sukidashi takabori) and depicts a peasant in a straw cloak and hat, with a hoe over his shoulder, crossing a low bridge on stilts. Above the man is a flock of 15 birds (geese?) flying in squally weather, as depicted by driving rain and bamboo bending in the wind (a similar scene on birds, wind and bamboo is shown on the reverse. The design is plain and without embellishment with, for example, gold nunome and yet the signature is inlaid with gold, even though it would be hidden by the seppa. The cursive script makes it difficult to read, the first character is unknown, but the second appears to be ‘chika’. Height: 7.8 cm, Width: 7.6 cm, Thickness (rim): 0.4 cm Thanks John (just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

Luca, I've been away from the NNB for a while and have just discoved your Kaga pdf. Excellent piece of work with kanji in the texts and references at the end. Published info don't get better than that. Thanks for all your work and making it available to all. I was interested to see the tsuba in B.5, C with a fuchi/kashira attached to it, in the Boston museum. I have just bought a sukashi tsuba with a kashira rivited to the seppa dai and was thinking to myself 'What sort of idiot would do that'. Guess there were at least two. great work, thanks again, John

-

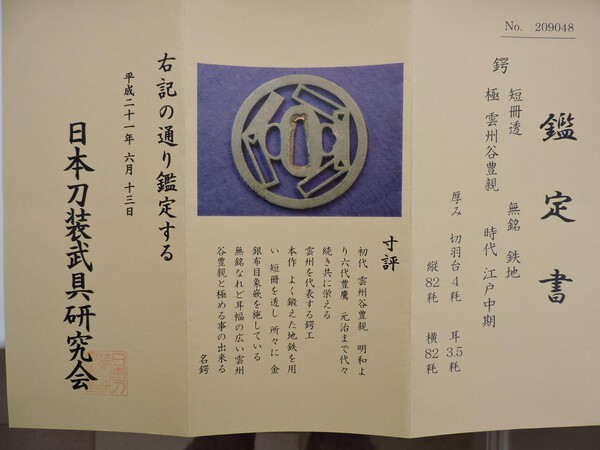

I bought a tsuba with a similar broad rim and flat profile that came with an ‘origami’ (not shown in auction), that turned out to be a NTKK kanteisho. The origami did not arrive until about a week later, during which time I could not assign a school or maker to it. In my limited experience the unusually wide rim made it difficult to assign. NTKK says it is Unshu Tani Toyochika. My inventory notes are below and pics for comparison are attached. Anyone got a better translation for the description of the design, Tan-satu-to, a half/short (tan) counter of books (satsu) that is open/transparent (to)? This large tsuba is of round flat sukashi form with what appears to be three carpenter’s squares cut out of a flat iron plate. The kanteisho describes them as tan-satsu-to (literally. Short-counters for books-transparent) The width of the rim is unusually wide, indicating that this is not the work of most of the sukashi schools such as the Kyo, Akasaka, or Owari. The tsuba is unsigned, but came with a box containing a label, in Japanese, attributing the tsuba to ‘Unshu Tani Toyochika’, i.e. Toyachika of the Tani school in the province of Unshu. The lot was also accompanied by a NTKK (Nihon Tosogu Kenkyu Kai) origami that arrived a week later confirming this attribution (see below). The Tani school was established in the Izumo no Kuni by Jirosuke Toyochika (working in the Meiwa period; 1764-72) and his son Toyoshige (working in the Kansei era; 1789-1801). There is also some gold nunome which is mostly worn away. The translation of part of the NTKK kanteisho, reading columns from right to left, is as follows: kantei-sho (鑑定書) - Appraisal No. tsuba (鐔) Tan-satsu-to (open half counter for books?), mumei (無銘), tetsu-ji (鉄地) – unsigned, iron XXXX XXXXXXXX ?Unshu Tani Toyochika Jidai (時代) Edo-chūkji (江戸中期) – time of production, mid-Edo period 厚mi - Dimentions Seppa Dai 4 mm, Mimi 3.5 mm Height: 82 mm Width: 82 mm Sunpyō (寸評) – Brief Review XXXX Shodai Unshu Tani Toyochika. Showa yori roku dai Toyotaka First generation Unshu Tani Toyochika until the Showa era sixth generation Toyotaka. Genji (1864) made daidai zokuki tomo ni sakaeru – Until Genji (1864) generations prospered together. Unshu o daihyo suru tsuba ko/ku-hon/moto saku- Representations of Unshu styles were made. Uki no tōri kantei-suru (右記の通り鑑定する) – The above is the summary of our appraisal. Heisei 21 year sixth month 13th day (June 13, 2009) Nihon Tōsōgu Kenkyū Kai (日本刀装具研究会) Best regards, John

-

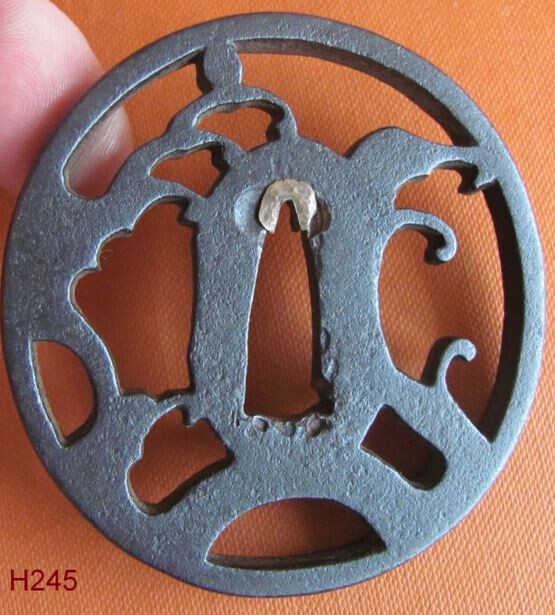

I seem to have a penchant for buying cast iron tsuba via commisison bids at small auctions where the photos are not very good. Here is my latest. I would challenge Ford's supposition that these are modern, based upon the context in which I bought these. I think that all three came from mixed lots that contained authentic pieces, some from quite large groups of lots which I assumed were from deceased estates. So I think that they were acquired many years ago when tsuba were cheap and there was no demand fo modern fakes. Here is the description from my inventory. This sukashi tsuba appeared to be an Akasaka (or possibly Nishigaki or Higo) tsuba from the poor photograph on the auction website. However, upon receipt it was obvious that this is a cast iron copy of an Akasaka design, probably made in Japan in the 19thC as a cheap sword fitting for an impoverished owner. The tell tale signs of casting are the glossy patina, flaking of the surface around the rim and fine ridge line near the centre of the piercings for joins in the mould. There are also two circular marks either side of the top of the seppa dai, which look like welding spots. I would surmise that these had been done at a later date, possibly to affix the tsuba to something as decoration. See ##019 and ##024 for other examples of cast iron tsuba. Provenance: Canterbury Auctions, Wednesday 10th April 2018, Lot 594 Height: 7.0 cm Width: 6.6 cm Thickness: 0.65 cm rim Some bids are diamonds, some bids are dust/rust. Its good to admit ones failures on NMB, quite cathartic. All the best, John

-

Thanks Ford for the clarification. It is interesting to look at descriptions of 'sandy brown' alloy tsuba in various catalogues and books. One auctioneer will describe nearly all such items as brass, another as sentoku and another as shinchu. I guess it needs someone to publish a book on Japanese alloys. Then we have differing compositions of brass, anything from 5% to 40% zinc, sometimes with a dash of lead, etc. So to misquote Star Trek 'Its brass, John, but not as we know it' Looking forward to the book, thanks again for the comment, John

-

Here is the tsuba im my collection that i think embodies wabi sabi. i think that it is Kanayama and I've posted it before in more detail. The iron is roughly finished, looking heavily rusted, but its not. Spokes have been removed to leave the simplest of designs. In summary a natural looking piece of old iron with lots of imperfections that has a lonely, empty feel to it. Wabi sabi as far as I'm concerned, Best regards, John

-

Thanks for the replies. Pete, Bruno, Curran, Steven: Shonai Shoami. That is a branch of the Shoami that I am unfamiliar with. The few examples that I have found so far show a wide variety of styles, so I would not have attributed this tsuba to that school. There were a couple of examples of similar workmanship, so thanks for the info. Its what the NMB is for after all, sharing ideas and learning. Pete. I'm not sure that I agree with you saying that they are just punch marks. The bottom ones do not seem to have any significant effect on the size of the nagako ana. I think that they are more for decoration, as I have seen on other 19thC tsuba made for export and have never been on a sword. Nagoya mono tsuba (cheap copies of Mino Goto) have a characteristic pattern of 10 large punch marks in all the half dozen patterns I have seen (treasure ship, pagaoda, Ono no Komachi etc). See discussion on NMB a couple of months ago. Although large marks, they are all the same pattern and obviously not for resizing the nagako ana. I suspect that these flower punch marks were used in several workshops in Edo. Thanks again for the info everyone, best regards, John Just a guy trying to learn and sitting at his PC waiting for the postman to deliver his next treasure from Japan

-

I’ll ask the usual questions at the start, namely any ideas on the school and maker, plus any ideas about the theme of the design, which I have not seen before? This large maru gata tsuba appears to be made of brass (sentoku) or closely related alloy giving it a slight red-brown patina. The scene continues over both sides and depicts a hanging scroll falling off what I assume is a wooden, two legged easel (in shakudo?) with a tying ring at the top. There is also a shakudo vase with a golden flower and long tapering leaves (daffodil?). This vase is on a separate, slightly sunken, lightly hammered, chocolate brown area, separated from the main body by a zig-zag line, possibly to indicate a violent event, e.g. perhaps the scene has been disrupted by a sudden gust of wind. Like a good fitting toupee, I cannot detect the join between the sentoku and the chocolate brown area, so perhaps it is not inlay, but a change in patination. The tsuba is fitted with a shakudo fukurin and has a pair of kogai hitsu ana. Staining and slight damage around the nagako ana indicates that this tsuba was once mounted on a sword and was not just a piece made for presentation, or the 19thC export market. The loose hanging scroll depicts Shoki (the demon slayer) picked out in fine gold inlay on a charcoal grey background (representing a sheet of paper), which is framed in sentoku(?) and copper, all on a shakudo scroll. Even the end of the pole at the bottom of the scroll is tipped in silver. The vase is finely inlayed with gold and the flower (daffodil) is probably gold. Altogether, a finely crafted piece of work, but unsigned (not that signatures can be relied upon). I reckon that the tsuba was made about 1800, give or take 50 years maximum. There were lots of skilled kinko artisans around this time, many signed their works, but some did not. There maybe two clues as to the school. On the face of the tsuba there are three flower shaped punch marks, one at each bottom corner of the nagako ana and a double at the point. None is complete, but may be a ca. 14 petal chrysanthemums. They look like tagane mei (chisel name) rather than attempts to modify the shape. The other clue is the representation of the scroll, which wraps around the rim to appear on both faces of the tsuba. To judge from auction catalogues etc., continuing the design on both the front and back of mixed metal tsuba seems to be in vogue during the first half of the 19thC. One of the aspects that I love about collecting tsuba is figuring out the scene that they depict. At the time they were made, I expect that the themes would have been well known to the average Japanese, but many have now been forgotten. I spent a long time wondering why someone would want to portray a scroll being blown aside by a gust of wind. Then I watched a Japanese version of the 47 Ronin and think that I may have found the answer. The Ako Incident, in which the 47 Ronin avenged their lord’s death by killing Lord Kira took place on 30th January 1703. OK, that was winter, but an early daffodil could have been placed as a decoration indoors in a vase, as shown on the tsuba. The popular version of events has Lord Kira hiding in a charcoal store out in the back somewhere. I can’t imagine the main charcoal store being close to Kira’s bedroom and maybe the story was exaggerated to further blacken Kira’s name (sorry guys, could not resist that one). A different version has Kira being found in a secret courtyard behind his bedroom, hidden by a large scroll, that maybe held a small quantity of charcoal for the bedroom heating. Perhaps the design on the scroll (Shoki, killer of oni) represents Oishi Kuranosuke killer of Kira. I have found flower punch marks (literature examples) on tsuba by Hagiya Katsuhira (Mito school, ca. 1870), Ichijuken Teruaki (Kato school, ca 1860), Funada Ikken (Goto school, 1844), unsigned Mino Goto, unsigned Hamano school (19th C), Oishi Akichika (1854, Oishi Akichika making a tsuba alluding to Oishi Kuransuke, see above?, Nah, coincidence) and Kano Natsuo. So I guess flower punches were used by many of the tsuba artisans in the 19thC, which probably reflects fluidity between the artists and workshops, many of which were in Edo. I would imagine that artisans fashioned their own tools and that making flower punches was part of the training in one or more workshops. I gather that many of the 19thC kinko artist used designs supplied by other artists on paper and I believe this is why we see so many 19thC kinko tsuba with apparently unique designs; there were so many to choose from. To my aesthetics, it makes a welcome change from the same old Kinai dragons, aoi leaves, carp, etc. of the 18thC and similar repetitious designs of other schools. Unfortunately, many of these high quality kinko works are unsigned. Why was this? My best guess is that this tsuba was made about 1800 in one of the Edo workshops (Goto, Yokoya, Nara, Kono), but this is not based upon handling similar examples, so feel free to challenge. Height: 7.8 cm; Width: 7.65 cm; Thickness (rim): 0.55 cm; Weight: 168g Best regards, John (just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)