JohnTo

Gold Tier-

Posts

266 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by JohnTo

-

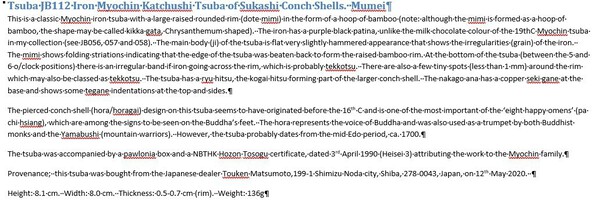

As its Chinese New Year I thought that I would post some Chinese dragons on a couple of Chinese? Nanban mask tsuba, rather than another Japanese version of a Chinese dragon. Like cast iron tsuba (no let’s not open that again) these tsuba invoke a lot of differing opinion as to where and when they were made. The first of my tsuba is iron with four masks (lions, demons?) at the cardinal points and four dragons’ heads together with a tama jewel. The dragons appear to be both male (upside down at the bottom) and female (at the top). Each side is bordered by what are generally termed ‘Drawer Handles’. The black iron is highlighted by gold nunome, which may have been added in Japan? The second of my tsuba is brass and only has two lion/demon masks at the top and bottom. There are still the four dragon heads, two females at the top with their mouths open (talking again?) and the two male dragons beneath with whiskers (this time the right way up). The two drawer handles have been replaced with four stylised dragons, each pair holding a tama jewel in their mouths. Comparing scratch marks on this tsuba with those from a Christie’s sale catalogue (1992), it almost certain that it the one from the Soame Jenyns collection One look at the nakago ana on these tsuba tells you that these were not made for a Japanese sword or polearm. Most people seem to call these ‘Canton Tsuba’ and were made in China, starting in the Momoyama period (pre-1600) up to the late 18th C. Others claim that the Dutch East India Company imported these from as far away as Shri Lanka (old Ceylon). This claim seems to be based upon the ‘Drawer Handles’ which look like the European sword guards and some examples (see photo from RB Caldwell Masterpieces) which seem to have VOC (Vrie Oostindiche Companie) around the seppa-dai (see photo). However, the ‘Drawer handles’ seems to have been used on Ming Dynasty guards and the VOC logo looks a bit ‘iffy’ to me. IMHO, I believe these tsuba may have been taken from Korean polearms as war booty, during Hideyoshi’s campaigns (1592-1598). The Joseon Koreans and Ming Chinese were allies and were armed with the same weaponry. It seems unlikely to me that these tsuba would have been commercially exported from China to Japan with the knowledge that the nakago ana was the wrong shape and had to be modified. Later Nanban tsuba may have had fancy seppa-dai, but the nakago ana was a ‘Japanese shape’. I don’t have any corroborative evidence for this theory. All the best, John

-

I see that Alex and Dale have posted pieces with brass inlay of abstract dragons, so let me add mine. This tsuba is highly polished iron with a brown patina resembling shibuichi, which is what the auction house catalogued it as. The shape is a rounded mokko gata (nade mokko or Otafuku gata) with the ji tapering towards the edges (goishi gata). The tsuba has flush inlay (honzogan) of stylised dragons in brass, two on the front and one on the back and is signed Kashu (no) ju Katsukuni. Flush brass inlay was a speciality of the Kaga tsuba makers and Haynes says there was eight generations of the Katsukuni family in Kaga working from ca. 1700 to 1880. Anyone any ideas on the origin of the abstract dragon design? Best regards, John

-

February 10th is the start of the Chinese Year of the Dragon. I’m sure many of you have fittings with dragons, so let me get the ball rolling with start with two tsuba of mine. Perhaps, as it is the Chinese New Year, I should post some Nanban Chinese dragons, but I thought I would post these two as they seem to have nice smiley faces and do not look particularly fearsome; a good New Year omen. I have attributed both of these tsuba to the 19thC Mito School based upon the observations that the artists tended to make large iron plate tsuba with a hammered surface and raised areas of iron which they carved in detail and left their work unsigned. The surface of both tsuba is a glassy chocolate brown, which why I think they are 19thC rather than earlier. Other schools which I think could be candidates for the makers are the Myochin and the Natsuo workshops. The first tsuba is a large (9.6 x 8.7 cm) rectangular plate tsuba showing a dragon among clouds and wrapped around a diamond shape (clan mon?) in the centre. Most of the design is formed by hammering the iron around the proposed design element to form an indentation and then carving the centre. However, the iron forming the dragons head has been raised above the plate before carving. The tsuba is highlighted in parts by a light application of gold, called kakihage (shadow), giving a more subtle effect than nunome inlay. The second dragon tsuba is also a large (8.4 x 7.8 cm) iron plate, which has been roughly hammered into shape and shows many lumps and bumps, which I hope that I am correctly identifying as tekkotsu, rather than being fooled by irregularities made to look like tekkotsu (clever these artisans!). The areas containing the clouds and dragon look like they have been indented into the plate using a pre-shaped stamp, but I think that it is actually skilful forging. The dragon has a welcoming, rather than fearsome, look and the eyes are gilt to impart some life into the critter. Although the dragon is a typical three clawed Japanese variety it also has three tails, namely a long curly one, another about half the length ending with what looks like a brush used for calligraphy and a short tail, again looking like a calligraphy brush. No idea why. Comments and further information welcome Best regards for the (Chinese) New Year, Regards, John (just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

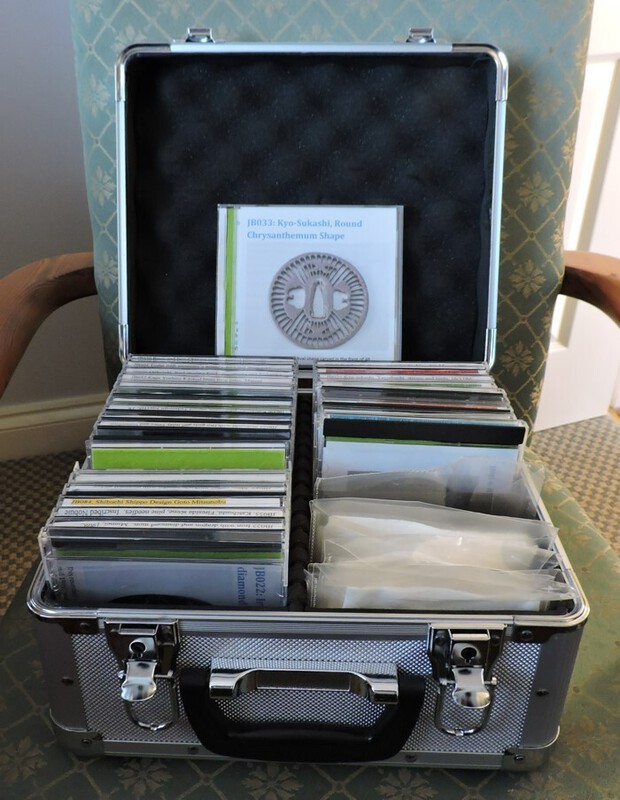

George wrote '(At the moment I could do with only two good ones, but I have a few extra rougher tsuba that at least deserve *something* to be stored in properly - oh, and I'm UK based if that's relevant)' Several years ago I posted my cheap way of storing tsuba in CD jewel cases. I took a lot of stick from purists. I still have quite a few stored in this way as I don't want to invest about £20 in a kiri box for a 'B' quality tsuba. The CD jewel cases can also be stored in a custom aluminium box for storage and transportation without coming loose. They also take up a lot less space, the aluminium storage box hold about 40. Best regards, John

-

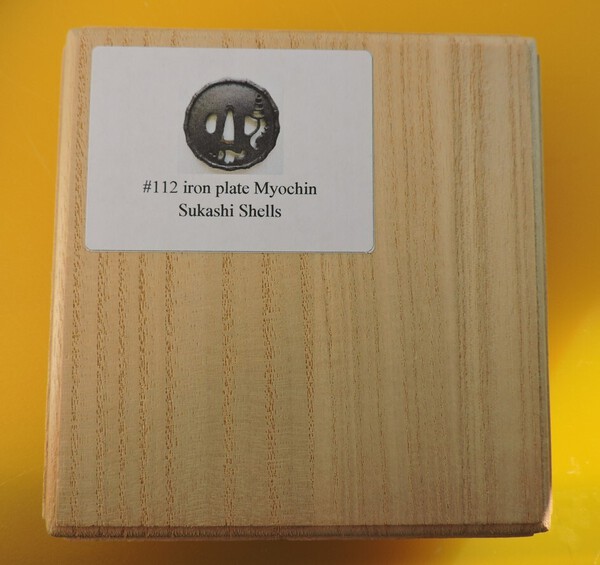

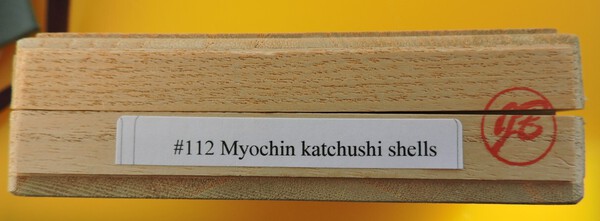

As Piers noted it can be difficult finding a specific tsuba amongst a pile of boxes if they are not labelled in some way. I put a label on top of the box with its inventory number and picture. On the one side (bottom) of the box I put a label with the inventory number together with my hanko stamp (available from Japan via Ebay). The stamp is a useful means to identify which way up the lid goes on the box and by placing the stamp in slightly different positions it ensures that the correct top goes on the box. Added to that each box contains a strip of paper (about 30 x 10 cm, long edge folded in three to fit in the box). One side shows photos, the other my description and notes (these are referenced to my main inventory). Always useful when you want to refresh your memory and sometimes think 'I got that wrong. I'll I have to update.' Photos of a typical tsuba set are attached. Best regards, John

-

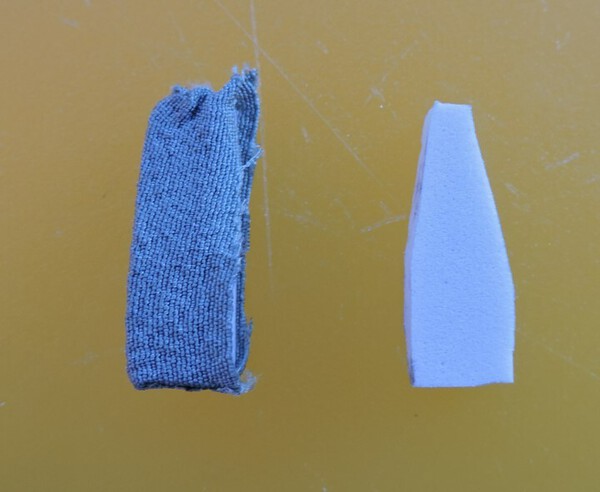

Hi Les, A timely query as I am just making a liner for a tsuba box. I like to throw out the standard Japanese liners, mainly because the pegs are held in with steel tacks and can damage tsuba if the peg breaks loose. I suppose I now have more than 30 in my refurbished boxes and may have posted notes before on how I make them. The current project is a bit unusual. By coincidence I bought a silver sake cup as part of a job lot at auction recently and it came with a tsuba style box, but large 11 cm square. I then bought a monster of a tsuba, 9.6 cm, without a box. The project is not finished yet, but here are some photos. Normally I make the liner out of EVA sheeting, but this time I decided to make one out of balsa wood. I prefer using the EVA. Custom pegs are easy to make with EVA. I still have to trim this one in the photo, but it gives the idea and is shown together with an EVA blank peg Covered one is on its side and awaits final trim. EVA blank is top view. Fina pic is tsuba in its new box plus covered liner and peg, not glued and trimmed yet. Hope this helps, Best regards, John

-

Hi Dan, Helpful post for new collectors. One point to comment on is the part about tagane . 'First, I look at the area around the nakago-ana to see if there are tagane-ato (punch marks around the nakago-ana). Those punch marks are made to fit the tsuba more securely to the tang of the sword blade. Those tagane-ato punch marks should appear “crisp” and could actually be punched fairly “deep” into the tsuba (on a cast piece they appear “rounded” and are fairly shallow).' Tagane-ato are also used instead of signatures. Some Higo tsuba have very shallow rectangular tagane (four at the top and seven at the bottom). NBTHK Hozon papers that I have seen with identical marks to mine attribute the tsuba to late Higo, rather than to a specific workshop or maker (see the three tree theme example attached). Nagoyamono tsuba are made of nigurome but often sold by auction houses and Japanese dealers as shakudo and have a characteristic pattern of three punch marks at the top and seven at the bottom. There are about 20 different themes apart from the one attached (treasure ship). I did post a warning about these sometime ago attributing them to 'Mr Suzuki's workshop', the name I gave to the unknown guy. These are often sold at inflated prices, IMHO, so buyer beware. Hope this is helpful, John

-

Sorry for the delay in acknowledging your replies, been away from the computer and tsuba for a while. Thanks for the examples and reference to the Kumamoto museum (very interesting exhibits) Please note that for some unknown reason my photos have been scrambled from the order in which I loaded them so they appear as 1. Example 2 2. Example 1 3. NBTHK Hozon for Example 1 4. My tsuba: Omote 5. Harunobu print of Potted Trees 6. My tsuba: Ura with tagane 7. NBTHK Hozon for Example 2 8. Christian Malterre picture 9. Christian Malterre text 10. ‘Akasaka’ Example Best regards, John

-

I bought the first tsuba in the pics below a couple of years ago (JB125) and was described as a Higo tsuba, an attribution that I was happy with at the time (and still am) given my limited knowledge. The tsuba is a kikka gata (chrysanthemum shaped) iron sukashi tsuba with a flat migaki-ji (polished) surface with light engraving (kebori: hair carvings) to highlight the blossom and pine tree design. The iron has a black patina with a fine crystalline structure with few apparent inhomogeneous iron inclusions (tekottsu). The design consists of a mixture of cherry (split petals) and plum (rounded petals) blossom with the branch of a pine tree. The sukashi is cut vertically through the plate with no rounding to the edges. The mimi (rim) is defined by the 28-petal chrysanthemum design and there is a slight rounding to the edges. The tsuba has ryu-hitsu, the kogai hitsu being of regular shape and the kodzuka hitsu is bordered by a blossom branch. The nakago ana has no sekigane and shows some widening at the sides and filing at the bottom to fit a blade. The interesting feature is the groups of small, shallow rectangular tagane at the top (four) and bottom (seven) of the nakago ana, which were almost certainly maker’s marks in place of a signature, as the tsuba is mumei. I’ll get back to these later. Statistics: Height: 7.9 cm, Width: 7.4 cm, Thickness (rim): 0.45 cm, Weight: 116 g The design seems to be depict one (or both) of the following stories. The first is the Noh play, Hachi no Ki (the potted trees), in which Lord Tokiyori, disguised as a priest, begs shelter from a former retainer, Tsuneyo Genzayemon, who has fallen on hard times. Tsuneyo and his wife are only able to offer the priest boiled millet for food and, as it is cold and snowing, they chop up their three precious bonsai (plum, cherry and pine) and burn them to keep their guest warm. Six months later Hojo no Tokiyori (ruled at Kamakura 1246-1256) summoned Tsuneyo and granted him three fiefs (Plumfield in Kaga, Cherrywell in Etchu and Pine-branch in Kozuke). The 28-petal chrysanthemum probably alludes to Hojo no Tokiyori. A yukioe print of a scene from the play is by Harunobu is attached. The second theme that this tsuba may relate to is the bunraku and kabuki play ‘Sugawara and the Secrets of Calligraphy’. The main characters of the play are Umemaru (plum tree), Sakuramaru (Cherry Tree), and Matsuomaru (Pine tree). In order to save the son of Sugawara, Matsuomaru used his own son as a decoy who was killed. Anyway, back to the tagane. I started to keep an eye open for tsuba with similar tagane marks and some reliable authentication (e.g. NBTHK). Below are just a couple that I found together with part of an article published by Christian Malterre (sorry Christian, can’t remember where I got this from so that I can acknowledge your work) that attribute these ‘kakushi tagane’ to the two Higo masters: Kamiyoshi Fukanobu and Kamiyoshi Rajuku. There is also an additional tsuba showing these tagane that was for sale on Ebay, but attributed the tsuba to Akasaka. The two tsuba with NBTHK Hozon papers are attributed to ‘mumei kodai Higo (unsigned late Higo)’, which represents quite a wide range of possible makers. Higo (now Kumamoto prefecture in Kyushu, southern Japan) was the home to four major (and numerous lesser) tsuba schools, namely: Hayashi, Hirata, Nishigaki and Shimizu (the founder Jinbei Shimizu renamed the school Jingo, famous for brass inlay). Higo tsuba were highly regarded in the Edo period as illustrated by the old saying ‘For the best katana go to Bizen, for the best tsuba look to Higo’. (Information from Yatsuhiro Municipal Museum website). The pattern of light tagane punch marks is obviously a ‘signature’ rather than an adjustment to the size of the nakago. The NBTHK does not seem to be averse to attributing mumei tsuba to a particular tsubako, but the best that they do with these characteristic marks is ‘Late Higo’, which encompasses a lot of workshops as well as artisans. I have found other examples, but either the photos do not allow close examination of the tagane or the nakago has been modified. My questions are these: Can these particular kakushi tagane marks be attributed to a particular artist/school, or were they used by several (unknown) artists in different workshops over different periods of time? Also were these tsuba faked a lot? Pictures: 1. My tsuba: Omote 2. My tsuba: Ura with tagane 3. Harunobu print of Potted Trees 4. Example 1 5. NBTHK Hozon for Example 1 6. Example 2 7. NBTHK Hozon for Example 2 8. Christian Malterre picture 9. Christian Malterre text 10. ‘Akasaka’ Example Best Regards, John (just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

There are plenty of scientific techniques which could clarify the cast iron issue: carbon-14 dating to show when the iron was smelted, isotopic and trace metal analysis to show where the iron ore came from and crystalline analysis to show the forging history. However no one is going to do these because these tsuba are junk and there are far more interesting research topics for scientists to put their name to and get funding for! I opened up a discussion topic some time ago about 'Mr Suzuki's workshop'. He was a name I attached to the owner of a workshop in Nagoya who made cast nigurome tsuba that look rather like shakudo, probably in the 18thC. He made about 20 different designs all of which had the same common features: size, single ryo hitsu,nanako ji and gilded sort of nanako mimi plus a pattern of tagane in place of a signature (three at top plus 2, 3 and 2 at the bottom) See attached pic of the treasure ship tsuba to refresh memories. These tsuba are still being sold by Japanese dealers as shakudo, Mino, etc when they are not and experienced dealers should know better than to pass these off as quality pieces. The point I am trying to make is that Japanese craftsmen have been 'forging' cheap quality tsuba in the Edo period, but nobody wants to become an expert in poor quality antiques? Best regards, John

-

Just taken delivery of a NBTHK Hozon Akasaka sukashi crane tsuba. While waiting for the tsuba to arrive Jimi-san sent several emails praising the tsuba. I thought that he might be just hyping it up a bit. He wasn't. Superb tsuba and I'm extremely pleased. Its text book Akasaka, which is what I was looking for and the iron is great showing the multiple layers of the Akasaka school, plus the tsurumaru design is particularly lovely. Had a little problem trying to pay by credit card, but PayPal worked OK. He has several other tsuba that I like the look of, but my collection debt is already rather large and despite holding my breath until I turn purple and stamping my feet etc, my (lovely) wife says no more money for the time being. Thanks Jimi

-

In a couple of Japanese samurai films, 'When the last sword is drawn' and 'Sekigahara' there are scenes where one of the characters is cleaning out his ears with a kogai. Regards, John

-

Hi guys, I hesitate to disagree with Ford, but Markus Sesko, in his book the Japanese toso-kinko Schools, page 129 under the information regarding one Dainichi Fucho, active Horeki (1751-1764) states that ‘According to transmission, Fucho learned the kinko techniques from Ugai Gorozaemon who belonged to an Osaka-based family of kettle casters who produced cast-iron tsuba as a sideline. Maybe Fucho refers with his craftman name to this context ‘Fu’ (Japanese reading ‘kama’) means ‘kettle’ and ‘cho’ among others ‘to make, to arrange’ (Japanese reading ‘kama’). I have no knowledge regarding Japanese tea kettles but information on the Internet implies that modern makers of testubin (kettles) are casting iron in the way that they have been for centuries. I also found this: ‘Named “tetsubin” in Japanese, this type of teapot goes back to the 17th-century. Made in Morioka city and Mizusawa city, both in the Iwate prefecture, the kettle is part of the Nambu Tekki category of ironware, which refers to all cast iron products crafted in the former Nambu area. Nambu Tekki itself has origins in the Nambu Kama kettles and ironware, which date back to the Sengoku period, which lasted between 1467 and 1600. Even today, these teapots are almost exclusively crafted in the Iwate prefecture by skilled artisans who use the same traditional techniques.’ I also found this article on the Internet, part of which is shown below, stating that cast iron was in use in Korea about 2000 years ago. The use of white cast iron in ancient Korea Jang-Sik Park & Mark E. Hall: iams 25.2005, 9-13 ‘Conclusions The results here suggest that cast iron was used to make iron and steel on the Korean peninsula by the time of the Korean Three Kingdoms Period (ca. 300-668 AD). The evidence suggests this occurred in both the north and the south of the peninsula. The microstructural evidence indicates that the iron and steel could be made from white cast iron in one of two ways. One way, the items were cast with white cast iron in a pre-formed mould and subjected to a simple thermal treatment for decarburization. The two arrowheads are examples of this method. This manufacturing method would allow mass production of the items. In the second case, white cast iron is decarburized and converted to iron and steel under the combined action of heating and forging. In this method, forging is used to accelerate decarburization. The armor scale and farming implement were made by this method. It is apparent from the present work that, from the early 1st millennium AD, inhabitants of the Korean peninsula practiced a complex ferrous metal technology that incorporated the use of white cast iron. Considering the geographical proximity, the influence to and from China cannot be underestimated, especially in the Koguryo state whose territorial boundary extended to Manchuria. While a Chinese text mentions the use of forging to assist in decarburizing, the metallography of contemporary Chinese artefacts shows little evidence of forging being utilized (see Wagner 1993: 291- 295, 480). Whether this technology was developed in Han China or in the kingdoms of the Korean peninsula requires further research.’ Attached is a picture of the largest cast iron surviving lion (40+ tons) in China cast in 953 AD. In another article by ‘Gunbai’ Iron and Steel Technology in Japanese Arms & Armors - Part 2: Smelting Process (gunbai-militaryhistory.blogspot.com) an extensive description of the tatara smelting process is given which claims there were two types, namely the Kera oshi and Zuku oshi (news to me as well). Here are a couple of passages, the whole article is well worth reading. ‘Unlike the Kera oshi, to produce steel with the Zuku method two phases are needed (hence the name "Indirect"). The first one is the smelting of liquid steel, pig iron or cast iron. The furnace is heated, charcoal is added and later on iron sand/ores; the process last 4 days, in which the slag is fully separated from the steel. The final product would be cast into moulds and then is brought into the Japanese "finery" which were closer to the furnace and decarburized into the required material; this is where the fining phase start.’ ‘After this reading I bet that nobody has ever heard of Sagegane but a fair amount of people would be familiar with Tamahagane. It is quite a mystery explain why one is more popular than the other; although is written practically everywhere, Tamahagane was not the only high carbon steel used for weapons and armor.In fact, according to some researches done in the past, the Zuku Oshi method which was established since the Kamakura period (1192-1333), not only was older than the Kera Oshi method, which dated back to the Tenbun Era (1532-155) but it was even more used throughout Japan.And is not an impressive feat; although blast furnaces are more sophisticated and advanced than bloomery ones, the Japanese probably obtained their technology from China which was already using blast furnaces, and until recently it was assumed that in China bloomery were not used at all (this thesis has been debunked by recent evidences, but blast furnaces remains the main source for steel and iron in ancient China).’ When I look at nanban tsuba in my collection I think they were made by Chinese craftsmen living in around Nagasaki using casting methods brought over from China. Unlike the poor quality Japanese cast tsuba I have, they have no casting seams, so I think they were finished off by hand and maybe subjected to a decarburisation process before being sold to poor samurai (of which there were an abundance in the 18thC). The tsuba are also characterised by a lack of rusting which, IMHO, indicates they were cast. OK, so I’m out of line with general opinion and I’m no expert, but the NMB is a discussion forum to present different ideas. It would be great if some cast tsuba were sent for carbon-14 analysis to determine when the iron was smelted, but ours is a minor historical interest and would be low down on the British Museum’s list of studies. Best regards, John (just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

Grev, Unlikely to be a securing strap as the slots would be hidden under the seppa. It would only work if the seppa on the blade side had a hole and the strap secured the wakizashi to the saya. Difficult to release. But if Lord Asano had such an attachment he would not have been able to draw his blade and attack Lord Kira and we would not have had the wonderful story of the 47 ronin. I think it would have to be a catch release as found on WWII swords with the button on the tsuka and the release arm in the tsuka. Regards, John

-

Additional ‘hitsu ana’ on Umetada tsuba - Tosogu - Nihonto Message Board (militaria.co.za) Tom, here is the link, I hope (Not too good at posting links) John

-

Hi Tom, I posted the same question regarding one of my tsuba on 29 Nov 2022 (see pic below but search for original posting in this forum). Title: Additional ‘hitsu ana’ on Umetada tsuba. It was decided that the slot was for a catch, as used in WWII swords, to prevent the blade slipping out I postulated that it might have been useful on a wakizashi as this would have been more likely to happen if the samurai was bowing really low while kneeling. If I'm not mistaken I also posted a picture your tsuba as another example which I found for sale on Aoi Art in Japan. Best regards, John

-

Hi Colin, One more bit of info for you. The genealogy chart from Markus Sesko's Genealogies...... toso-kinko Artists (a book every tsuba collector should have) that shows Tomonao's fit in the Ichiryu School (looks like it may have loaded upside down, sorry, it was saved after rotating the right way up). Regards, John PS I was not the underbidder who forced the price up, so don't blame me for the cost.

-

Hi Colin, Glad you liked my hurried reply (I was going out this evening). Yes it was a nicely made tsuba and I fancied it to make a pair with mine to show the different techniques used. I had looked up the artist in Haynes beforehand, so here is some more info on Tomonao. Haynes number H 10001.0, Family: Kageyama. Other names (you know how they liked to change their personal names) Kosetsuken, Ryuryuken, Seiryuken and Yoshiro. Worked in Mito in Hitachi province. Dated example 1846 Student of Hirano Tomomitsu (H 09967). Two shibuichi tsuba described in Haynes. One Mosle p.492 #1582 Ebitsu in the rain. Other A. Beit, London boy playing flute riding on ox dated 1846. Both signed Kosetsuken Tomonao. Hope you enjoy it when it arrives. Best regards, John

-

Hi Colin, Congratulations. I went to see this tsuba as the auction house was nearby. Like you I thought it was shakudo from the auction house photos (as you have copied and posted), but in fact the base metal was brown when seen in real life, i.e. shibuichi. The auction house said it was bronze. So my bid was much lower. The tsuba depicts the story of Choryo (Zhang Liang) a Korean(?) hunted by the Chinese Han government with Kosekiko (Huang Shigong, lit ‘old man yellow rock’) at the Yishuidi bridge. The old man, Kosekiko, began teaching Choryo the art of war and to test him deliberately dropped one of his shoes in the river and ordered Choryo to retrieve it for him. The shoe was grabbed by a water dragon, but despite the insulting order, Choryo retrieved the shoe, and placed the shoe back on Kosekiko’s foot. The old man (Kosekiko) then arranged to meet Choryo on three occasions at the bridge; the first two occasions Choryo was late and was scolded, but on the third time he waited all night for the old man. The old man then gave Choryo a book about military strategy (Taigon Art of War) telling him to return in 13 years time when the old man would appear as a yellow rock. Choryo did return, found the rock and built a shrine to Kosekiko. I have a similar, shakudo tsuba by Katsuhisa, and found a print of the scene by Kano Tsunenobu see attached. The surface of the plate is essentially migaki-ji (polished), whereas the bridge, dragon and rock have been given an ishimi-ji (stone) finish. The design is cut in shishiai-bori (motif flush with the surface) mainly using a katakiri chisel (sloping on one side to look like brush strokes). The design is picked out in gold and silver hira-,or hon-, zogan (inlay flush with surface) and is sometimes called Kaga-zogan as it was commonly used by Kaga craftsmen, including this artist. The tsuba is signed using a fine chisel (kebori) Kuwamura Gen’emon Katsuhisa (桑村 **克久), with a kao. Sesko (p 326) lists a Genzaemon Katsuhisa (same kanji) of the Kuwamura School in Kaga, born Genroku 7 (1694) who had the go ‘Jokyu’ and this would seem to be the maker of this tsuba. He was still working in Horeki 8 (1758) and there is a work signed Kuwamura Jokyu at the age of 65 (1758). Katsuhisa and his brother, Yoshihiro, were the sons of Matashiro (later Cho’emon) Morikatsu, who studied under Goto Kakujo and used the go ‘Sojun’ and was employed by the Maeda family.

- 14 replies

-

- 12

-

-

-

These tsuba are fairly common and have turned up frequently in auctions over the years. They also seem to have been made by different artists from a number of schools. One of the first that I saw was from the R.B. Caldwell collection (Lot 24) in 1994 and was signed Heianjo Sadatsune, with a NBTHK Hozon certificate. This was virtually identical to mine (Pic attached), but is signed Bushu ju ???. The name was inscribed too indistinctly and is now unreadable! Anyone know how to restore a feint signature like they do in forensic labs with the serial numbers on guns? Anyway, mine is Height: 6.95 cm. Width: 6.5 cm. Thickness (rim): 0.25 cm. Weight: 82 g Best regards, John

-

I don't think that DeCorroder and Evaporust are similar. Evaporust seem a bit cagey about their ingredients, just vague mentions of chelating agents Quote ' The Selective-Chelator is not strong enough to remove Iron-to-Iron bonds from un-corroded steel and does not harm the underlying metal. The Chelator is too expensive to use large quantities in the finished product. An organic chemical that easily loses sulfur to form ferric sulfate was added to remove iron from the Iron-Chelator complex. This allows the Chelator to remove more Iron from Iron Oxide. The sulfur-bearing compound is much less expensive than the Chelator and makes Evapo-Rust™ economical to use. Evapo-Rust™ has a chemical carrying capacity of 300grams of pure, dry rust per 5 litres.' De-Corroder is much more expensive £10 for 100 ml, Evaporust £20 for 1000 ml. regards, John

-

Tsuba #3 was more of a challenge and I have posted this separately below for clarity with the photos. Tsuba #3 is essentially a round, flat iron plate with a slightly raised engraved Chinese landscape scene with a few small pieces of copper and silver inlay highlights and some crisscross gold nunome (see pics). It was also covered in red rust, so the first treatment was to clean half of each side with cotton buds and WD-40. A lot of loose red rust came off on the cotton buds and the surface darkened with the WD-40. I gave the tsuba several more cotton bud/WD-40 treatments (see pics). At this point it became evident that the tsuba was either never patinated, or more likely, a previous owner had tried to remove the rust with acid causing the bare metal to be exposed and become more susceptible to rusting. Trying to remove the thicker black rust with a piece of bone and WD-40 was slow and relatively unproductive (rust did come off, as evident from cotton bud swabs). It was at this point I decided to give Renaisance Metal De-Corroder a go (many of you will probably be familiar with Renaissance wax used in museums). De-Corroder is an amine complex of hydro-oxycarboxylic acid in an aqueous solution with a pH of approximately 4.0 (slightly acidic). It claims to ‘selectively rupture the bond between base metal and corrosion layer, reducing rust to sludge which is easily wiped or brushed away.’ The instructions talk about immersing the object but, as the bottle contained just 100 ml, I applied the solution to a couple of badly rusted areas with cotton wool wrapped around a wooden cocktail stick, placed the tsuba in a plastic CD jewel case (to prevent drying out) and left it overnight. The next morning there were two patches of black gel on the tsuba which I washed off with water and a cotton bud to reveal most of the rust had gone, revealing bare metal (see pics). Note: I always use rain water rather than tap water to wash iron tsuba as I don’t want dissolved salt residues getting into open pores in the iron and catalysing further rusting. Encouraged by these results I applied about another five treatments over the entire tsuba, including the mimi, nakago ana and hitsu ana (see later). Between applications the gunge was washed off (water, cotton wool buds and electric toothbrush) and the engraved areas scraped out with wooden toothpicks before drying overnight on a radiator. After that no further improvement seemed evident, the remaining stubborn black spots (see pics) did not seem to go and I considered these as being ‘patina’ rather than ‘rust’ thus preventing the De-Corroder from penetrating. I was left with an essentially bare iron tsuba with copper, gold and silver(?) inlay still intact and shiny. Next stage was to patinate the iron and I decided that a deep brown rather than black patina would be most appropriate based upon the Kaneie tsuba in part I and Choshu Chinese landscape tsuba in my collection. For this I used Birchwood Casey Plum Brown Barrel Finish, intended for restoring muzzleloading guns. This should be applied at 130°C and to do this I placed the tsuba on a gas BBQ grill and wiped the solution on the hot tsuba with some of my wife’s cotton makeup pads and cotton buds (for the nakago and hitsu ana). After about 5 applications I had achieved a rather muddy looking and powdery finish, much to my disappointment. WD-40 improved the surface somewhat and removed loose patina and then I used a wax from a church bell foundry, which finally gave an acceptable finish. At this point I stopped. Initially I did not attempt to remove the rust from the nakago and hitsu ana, just as the previous owner had neglected to do (in accordance with Jim Gilbert’s advice). However, I could see little point in leaving this thick layer of rust so this was also given several treatments with De-corroder and revealed something quite unexpected; alternating bands of bare metal and dark rust (see photos). These striations went around the entire surfaces of the nakago and hitsu ana and I estimated there were about 10 light/dark bands across the thickness of the tsuba. The iron had been forge folded at least 3 or 4 times (8-16 layers) before making the tsuba and was not just a plain old piece of homogenous iron as I had assumed! My admiration for the artist leapt at this point. I also felt that this explained the 1 cm square patch on the surface of the ji next to the hitsu ana. It was where the rust had tunnelled between the layers and lifted the thin iron surface layer away from the ji (see pic). I did consider polishing out this patch and maybe polishing out the rust pits in the mimi with fine emery cloth and abrasive powders, but decided that this is where I should stop. In conclusion, I considered tsuba 2 and 3 to be beyond commercial restoration by a professional and my main aim was to remove areas of active rust and prevent further corrosion. Also to experiment, learn and have a bit of fun. I was particularly impressed with the action of De-Corroder on iron as it seemed to act as claimed, namely softening up rust while leaving the base metal unchanged. Red and black rust are essentially the same iron oxides as the patina found on iron, however patinas are tightly bound fine oxide particles which prevent further corrosion. De-Corroder does not seem to easily remove the patina rust from iron, but I have not dared tried test this hypothesis on a rust spot on an iron tsuba with an otherwise intact patination. So beware, I am not advocating its use on all tsuba! Have I rescued or wrecked these tsuba? I’ll let the NMB jury decide. Best regards John (just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn) Photos 1: Omote as bought, with kogai hitsu ana on left rather than right side. 2: Ura as bought 3: Omote after several WD-40 cleans and bone abrasion 4: Ura after several WD-40 cleans and bone abrasion 5: Ura with two initial areas covered with de-Corroder after standing overnight. 6: Ura after De-Corroder washed off. 7: Omote after 5/6 treatments of De-Corroder showing residual dark spots of patina/rust. 8: Ura after 5/6 treatments of De-Corroder showing residual dark spots of patina/rust. 9: Omote after patination 10: Ura after patination 11: Folded layers of iron exposed in nakago and hitsu ana (side 1) 12: Folded layers of iron exposed in nakago and hitsu ana (side 2) 13: Area on Ura believed to be due to loss of a single layer of forged iron

-

Opinions amongst tsuba collectors differ as to how to treat rusty iron tsuba, as often illustrated on the NMB over the years, so I thought that I would submit my treatment of three rusty tsuba in my collection to open some debate. Have I restored them or wrecked them? The three tsuba came in a mixed lot of five at a local auction; the other two, being cast (nanban and Akasaka copy) were free of rust. As they were cheap, grimy and rusty I bought them as a restoration project. Tsuba #1 was in relatively good condition with just a few areas of red rust. It was also signed Yamashiro Kuni Fushimi ju Kaneie; the main reason for buying the lot. The only treatment that I have given this tsuba is to wipe off the red rust using cotton buds soaked in WD-40 and then to place the tsuba on a radiator to drive off the oil residues. Personally, I like WD-40 as it is a modern product developed for the aircraft industry and scientifically designed to penetrate rust. I know that many collectors like to use the traditional chogi oil but I note that the Japanese dealer Aoi Art no longer uses this on blades as they consider that it promotes staining and now use high quality machine oil. I do think that the treatment may have darkened the brown patina, but can’t be sure and I’m pleased with the result as no rust has reappeared on the tsuba in more than a year. Tsuba #2 is an aoi-gata tsuba, probably for a tachi, but I’ve taken the photos katana style. This tsuba was pretty grubby and has only been given the WD-40 treatment together with a clean of the inome bori (boars eyes) piercings with a dental hygiene brush, again soaked in WD-40. The iron has definitely taken on a darker colouration after placing on a radiator, but whether this is due to the WD-40 or just the removal of the surface dirt I can’t say. There are shiny black patches on the tsuba and I’m not sure if this is the original patina or remnants of a lacquer coating. At this point I’ve stopped any further treatment and the tsuba has remained rust free for the last year. Any suggestions for further action? You may notice ‘white rainbows’ above the middle of the tsuba, these are just lighting artefacts caused by taking the photos on a windowsill, sorry. I've posted tusba #3 separately below so the postings don't get too big Regards, John (just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn) Photos 1: Kaneie original omote 2: Kaneie original ura 3: Kaneie omote after WD-40 4: Kaneie ura after WD-40 5: Aoi-gata original omote 6: Aoi-gata original ura 7: Aoi-gata omote after WD-40 8: Aoi-gata ura after WD-40

-

Hi Dan, I have been experimenting with Renaissance Metal De-Corroder on a badly rusted tsuba. This is an amine complex of hydro-oxycarboxilic acid in water at a pH of 4.0. It claims, and my observations agree, that it ruptures the bond between rust and iron without having any significant effect on the sound metal. Easier than picking away with bamboo or bone. Leave on overnight and wash off with water using a dental brush or Q-tip to remove the softened rust. As you are talking about the INSIDE of a fuch/kashira I assume that you are not worried about damage to the patina. I cannot guarantee that this product will not harm the patina. The tsuba that I have been working on had evidently been 'cleaned' by a previous owner with acid and the patina lost before the tsuba was put aside and allowed to rust again. Long before I got it as part of a job lot. I am I the process of writing up my experiments for discussion/criticism on the NMB. As I indicated, if preservation of the patina is important then this may not be the appropriate treatment as patina is just a type of rust. I have been looking through my collection to find a cheapo/poor quality iron tsuba with a rust scab to see if the scab can be removed without damage to the surrounding patina but have not found a candidate yet. Best regards, John

-

Hi Jean, I was only going by your original pics. I've attached part of one and highlighted the lines on the inside of the mimi. They look like casting edges and appear in both your pics. But as I said it may have been your photos. Without having the tsuba in hand that is all I had to go on. Your latest pics look OK. Best regards, John