JohnTo

Gold Tier-

Posts

284 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

1

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by JohnTo

-

Thanks for the replies, especially from John L. I'm assuming that the references that John gave are from Haynes, which unfortunately I don't have. There was a comment about the design overflowing into the seppa dai. There are also decorative punch marks on the reverse, indicating that the nakago ana has been modified to fit a balde more tightly. I often see this in 19th C tsuba that were made as works of art and never intended to go on swords, even though they may have copper inserts and punch marks around the nakago ana. I assume that these were put on to enhance the feeling that the object is in fact a tsuba and not just a decorative piece of metal.

-

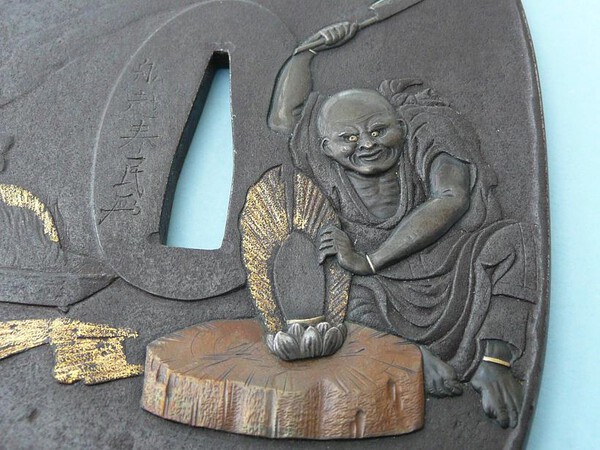

Minkoku/Shunmin Tsuba Can anyone help with the maker and subject of this tsuba? I bought this tsuba at a London auction nearly 20 years ago. Its signed Funakoshi Shunmin (with kao) and the artist was also listed as ‘Ikedo Minkoku, son of Someya Chomin and a pupil of Kono Haruaki’ with the dates 1833-ca. 1909. (other references give 1828-1816). The tsuba is iron (8.5 cm) with copper, silver and gold details. Whether or not the tsuba is an authentic piece by Funakoshi Shunmin, the carving of the figure’s robes in particular is of exceptional quality (in my opinion). The main subject was described as ‘a disaffected priest cutting the mandorla of a Buddhist statue with a cleaver’ and it was this that attracted to me to the tsuba as I recognised this as being a representation of the famous tale of the Chinese Zen monk Tanka (Tan’hsia, 739 -834, or 824) who stopped overnight at Yerenji. As it was freezing, he took down one of the wooden carvings of Buddha, chopped it up and set fire to it keep him warm. Next morning, the head monk of the temple was a little upset, to say the least, and berated Tanka, who started to rake through the ashes saying he looking for the bones (or sairas) of the cremated Buddha. The head monk called him an idiot (or something like that), informing him that there would be no cremated bones, as it was just a piece of wood. To which Tanka replied, ‘Well, if it was just a piece of wood, hand me down another carving and I’ll burn that as well.’ I particularly like the demonic look in Tanka’s eyes and when I purchased the tsuba, it had been over cleaned and his face was bright silver, but has now tarnished, as has the copper chopping block. The silver? Edge to the cleaver has remained bright. The gold on the mandorla has been lightly applied (I think the technique is called kakihage). Obviously this tsuba was never intended to go on a sword was made purely as an object d’art and I would guess that it was made around 1900. So onto the questions. Ikedo Minkoku/Funakoshi Shunmin (or Shumin) seems to be well documented, but not very well in any references that I have. The Genealogy charts of Markus Sesko lists a Shumin as the second (possibly third or fourth) son of Shomin of the Unno Shomin school. The Boston museum (see Lethal Elegance, Joe Earle) has a tobacco pouch with metal work made by him and signed Ipposai Minkoku, but unfortunately this was one of the few examples in the book with no photo of the signature. The British Museum has a shibuichi inro case signed Funakoshi Shunmin saku, with differences in some of the kanji to my tsuba (different hand or just change with time?). There seems to be various netsuke, inro, tobacco pouches, silverware made by Minkoku/Shunmin (with various Romanisation spellings and maybe not all the same guy), but I can find no tsuba, fuchi, kashira, etc. Also, my tsuba is iron, yet he seems to have specialised in soft metals. I have never come across any other kodogu by him in auctions. The spellings of the names mentioned above are as written in the references that I found and I’m assuming that these are just differences in Romanisation rather than differences in actual artists, but I may be wrong. I appears to me that the artist trained as a kodogu maker, saw that the age of the sword was coming to an end and switched to making ornamentation for the ‘fashion’ market. He also seems to have alternated between signing Minkoku and Shunmin, but I’m not sure why. Any info on this artist or his sword fittings would be appreciated. Thanks, John

-

I’m sure you’re right. It’s a cast tsuba. Had it been copper based, rather than iron, I would probably have quickly come to that conclusion without your help. Casting would also explain the patina. I’ve always thought that casting iron into a small mould would not have been an easy task (compared to copper) and considered casting iron tsuba to be a commercial waste of effort in the ‘reproduction’ market. For this reason I tend to be a lot less wary of iron rather than soft metal tsuba. Friends often point out Chinese soft metal tsuba to me in antique markets, but I’ve never seen an iron one. Not that I think that this is a modern Chinese tsuba. One of the likely schools that I had thought the tsuba may have come from was Yagyu (as suggested),or Kanayama, but the quality was not there. In view of the metal (iron) and the similarity to Yagyu, I’m inclined to think that it is a 19thC Japanese cast tsuba intended for the export/souvenir market. It’s still a useful addition to my collection as it’s an example that I have not got (hopefully) and an educational piece. And don’t worry, I did not pay a lot for it. Thanks for the help.

-

I bought this wakizashi tsuba amongst a job lot at a local auction (photo 1). Size 6.4cm x 6.0cm. 0.7cm thick at rim, 0.4cm at seppa dai. It’s not a great piece, but has features that I think it reveals something about its manufacture. Overall it looks like just another rather crudely forged, unsigned, iron tsuba of no particular interest. I would not like to hazard a guess as to the school, it’s easier to say what schools it does not belong to, e.g. Kyo sukashi, Echizen Kinai. It probably could have been made in any of many smithies anywhere in Japan. Anyone like to make a guess? Firstly, the damage to the surface, rather than rusting, has resulted in flakes of the patina becoming detached. I therefore deduce that this thick layer of purple/black oxidation was produced by long exposure in a hot forge, rather than the thin patina seen in many tsuba, which has often rubbed away in parts. The second interesting feature of this tsuba is what would be described in a sword as mune aware. A definite crack mid-way along three sides of the tsuba can be seen (photo 2). The fourth side has several ‘pock marks’ and may indicate hard steel tearing apart along the seam (photo 3). The inner surfaces of the cut out design also shows distinct lines along the middle of the plate. In most cases the lines on the inner part of the tsuba appear as positive projections from the surface, rather than cracks (photo 4 and also the ‘fuzziness’ along the inner edges in photo 1). These projections may be iron squeezed out from the layers or rust preferentially forming along the seam. My interpretation of these observations is that the plate was formed by folding over a thinner plate in half. The inner steel may have been softer than the outer steel or possibly a softer steel was sandwiched in (like kobuse sword forging) and attention was focussed on sealing the outer rim of the tsuba. When the central section was thinned the softer core steel was squeezed out in the joins in the mid-section of the tsuba. I have never seen evidence for such steel folding in a tsuba before (other than tsuba with definite grain patterns), but then I tend to just take superficial looks at tsuba at auctions and only study those in my collection in detail. Maybe many tsuba are made from a final single folded piece of steel rather from cut out from a large stock plate (which may be forged and folded many times) and this example only shows the joins between the layers because of poor forging. Comments welcomed.

-

Thanks for all the replies guys, sorry it has taken me so long to respond, but I have other interests. The general opinion appears to be that this Yasuhiro is a gimei. One question that I have with this opinion is why would a faker want to copy the work of such an ‘average’ swordsmith? I say ‘average’ as Nippon-To by Inami Hakusui list swords from about 400 swordsmiths with values ranging from 1,000 to 100,000 yen (1935 prices). Yasuhiro (I) is rated at 6,000, which places him in the bottom half. If I were a forger I would be copying someone in the top 200. Robinson does not include Yasuhiro in the top 15 Shinto smiths. Not that I believe that the blade is by Yasuhiro I, more likely by Yasuhiro III (based mostly upon a hunch, as I can find no examples attributed to him, but the change in shape of the nakago jiri and more cursive style of the signature may be more consistent with a change in style over about 70 years ). Less likely the blade is by Yasuhiro II or a gimei Yasuhiro II (even less reason to copy II than I). Unfortunately, we in the West are limited in our reference material. Which brings me to the subject of forgery. I remember being told about 40 years ago by an experienced collector of an old Japanese saying, viz: ‘Out of every 10 blades bearing the signature Masamune, 11 would be fakes’ (nice gold inlay ‘Masamune’ tanto sold recently in London in Part I of the Wrangham collection!) and reading that the Shinshinto smith Kawabe Masahide was described by his detractors as being in charge of the ‘forging’ department. I also remember going to see the Stowe school ‘Yasutsuna’ (9th C) when it came up for sale (beautiful blade), but thought to be a Kamakura forgery, so forgery of Japanese swords has a long tradition. I imagine that forgery reached its peak in the 19th and first half of the 20th century when swordsmiths were struggling to make a living. I believe that the famous 19thC forger Kajimei started out by documenting oshigata of famous swordsmiths and so was able to copy their signatures quite realistically. Would he have changed the nagako jiri in view of his great reference material? I would expect that the majority of gimei made in the last 150 years would be shinshinto blades as the forger would not have to bother about aging the nagako (rust) and would also be familiar with the forging style, having possibly worked with the smith being copied. How prevalent was forgery in the Tokugawa era, which was effectively a police state with harsh penalties for breaking the law? Were daimyo complicit in running forgery smithies in their fiefdoms in exchange for a percentage of the profit. And what about today? With all new swords having to be registered in Japan and made by licensed swordsmiths what is the chance of a modern blade (say post 1970) being a forgery? Josh states that swordsmiths use an inked in signature before chiselling. I would also think that this was standard practice. Consider the Yasuhiros, nothing could be worse than to finish chiselling a chrysanthemum and finding that they were half a petal out! I was on an English brewery tour last week and visited the cooper’s section. Apparently, after finishing his apprenticeship, the cooper is given a token with his initials to use as a template when signing the beer barrels that he subsequently made. An ‘official signature template’ was probably common among (semi-literate) artisans worldwide. I can easily imagine the master of an apprentice swordsmith popping next door to the woodblock artist and having a signature stamp made for the new ‘journeyman’ to ink in on all swords that he made before chiselling out his signature (that is apart from any really good swords that apprentice made, in which case the master would sign and attribute these to himself! Are these gimei?) Hoanh and Chris say that the mekugi ana is in the wrong place and the hamon is atypical, having tobiyaki. The Nihon To Koza, vol V has a good section on gimei and shows two shoshinmei of Ishido Korekazu, dated just one year apart, in which the mekugi ana is above the signature in one example and right between the first two characters in the second. So, the placing of the mekugi ana does not appear to be a hard and fast rule with every smith. The example in Nihon To Koza has a suguha hamon and the one in Fujishiro has tobiyaki, so what is typical? It’s not that I am in denial regarding the authenticity, I just like to look at all angles, rather than just dismissing it as gimei because it is not a text book example of Yas I. After all, out of 100 Yasuhiro blades I would expect 30 Yas I, 30 Yas II, 30 Yas III and 10 gimei, from a simple statistical view. Of course a shinsa would be useful, but I live in the UK and I have another sword to have polished first (I don’t think this one is gimei as, although it is signed and dated, I can’t find the smith listed anywhere!) Thanks for all the comments, they are all valid and have prompted me to look into the question of gimei a bit deeper. So thanks for the stimulus. How many of us make sure the labels on our clothes are fully visible so that everyone else can see we only buy upmarket designer items, even though they are probably churned out in a sweat shop in Bangladesh? I’m always amused when I read about some piece of art, which has eventually been attributed to ‘the master’ (following a lot of pressure by the owner), rather than being a studio piece. Overnight the value may increase 100-fold, but the intrinsic artistic quality of the item remains unchanged. I suppose ‘the name’ is everything, in ancient times as now.

-

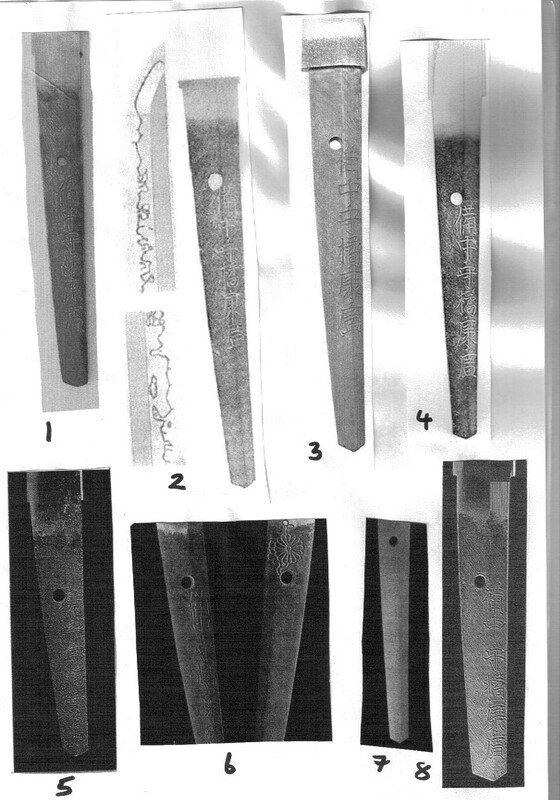

I logged onto the Nihonto Notice Board hoping to find some info regarding Yasuhiro and low and behold found this discussion. It was of particular interest to me as I believe that I was the guy that bought the sword in question. So let me add my thoughts. Firstly, let me say that I bought the sword because of what was on the other side of the habaki, though I must admit that the signature did make me put in a higher bid. Secondly I don’t subscribe to the assumption that the old kaji spent careers, often spanning several decades, paying particular attention to carving their signatures in exactly the same way and with the same chisel (unlike today’s smiths who are making swords for the art market). I guess that some were also semi-literate (better than their European counterparts though). All the signatures that I have seen (in print) show variations and being a statistician, who specialised in a field dealing with the identification of outliers within small sample populations, I’m reluctant to draw firm conclusions based upon these examples. I’ve attached a collage of signatures from various sources and these are as follows: 1> Sword under discussion 2> Shinto Shu by Fujishiro page 77 3> Sword for sale. (NBTHK Tokubetsu Hozon, Yasuhiro I or II) 4> Advert 5> Wakizashi in British Museum (ex-Lloyd collection 1958.07-30.144) shown in Cutting Edge #45 6> Advert (NBTHK Tokubetsu ‘higher’ to Yasuhiro I) 7> British Museum (ex-Lloyd collection 1958.07-30.141) also shown in Cutting Edge #43. In my opinion this blade has a rather deep sori (2.4 cm) for a 17thC blade! 8> Wakizashi Compton II lot 288 (NBTHK Tokubetsu Kicho to Yasuhiro I) All examples were signed Bichu Ju Tachibana Yasuhiro (some mention a Kiku but were not usually shown) and I’ve focussed on a couple of the characters for discussion, namely ‘Chu’ and ‘Yasu’ The ‘Chu’ in #1 is definitely the most curved and has the greatest disparity between the length of top and bottom horizontal strokes, though most of the other examples show fluidity to this character, with the exception of #6 which is rather rigid and angular. The character ‘Yasu’ in #1 has three horizontal strokes in the centre, much like examples 2, 3, 4 & 7. The ‘Yasu’ in #6 has very distinctive upward ends (ticks) to the horizontal strokes on the left character, far more than #8, Compton’s blade which also has an NBTHK TK paper. Couple this to the stem and leaf on the Kiku and I would have put this so far out of line with the other signatures as to be gimei! The Compton blade appears to have less distinctive ‘ticks’ to the end of the horizontal strokes in ‘Yasu’. My guess is that these two are Yasuhiro I and the other blades II & III. To my untrained eye the signature of #1 seems most closely related to 2 & 7 and the position of the first character in relation to the mekugi ana in 1 and 7 seems similar. Add to this the sugikai yasurime, but take off the more rounded tip of the nagako jiri and I’ve still got an open mind as to whether it is a genuine Yasuhiro II or III. If not, it is by someone familiar with the Yasuhiro style. However, all the discussion has been about the nagako. I bought the sword after just looking at the other end for just one minute. Despite the grubbiness, there was no serious pitting or edge nicks. The hamon was visible (see photos) and resembled example 2. Clouds of nie were clearly visible around both upper and lower parts of the choji midare hamon, which showed nice crab claws and tobiyaki floating above the low parts of the hamon. Itame hada from what I can see. The only unfortunate thing about this purchase is that, as it sold for maximum, I’m out of cash to have it repolished, something I feel this sword richly deserves.

-

For comparison I've attached a photo of a Tadatsugu tsuba in my collection, which I hope you will find useful. Description: An iron katchushi (armouror’s) tsuba in circular form with a shakudo mimi, the plate pierced on one side with a kirimon (paulonia badge). Signed Tadatsugu and accompanied by a NBTHK Tokubetsu Kicho paper dated Showa 43 (1968). This may be the Tadatsugu of the Umetada school in Yamashiro who died in the first month of Empo (1678). Purchased from Sotherby’s, London, 30 March 1994, Lot14 as Part of the R.B.Caldwell Collection. Height: 7.0 cm Width: 6.8 cm Thickness: 0.5 cm John

-

Thanks for the information. You are probably right about it being a modern copy, but the surface is different from any etched examples that I have seen. It was cheap, so it still makes an interesting addition to my collection. I remember being told of an old saying over 35 years ago 'Out of every 10 blades signed by Masamune, 11 are fakes.' Guess the same is true of tsuba to judge by the number of obvious fakes around. John

-

Can anyone give me information about the surface patina on a tsuba I have recently acquired? I bought the tsuba on-line and thought that it was just a rusty tosho tsuba. However when it arrived I realised that this was like no 'rust' I had seen before. The entire suface is covered with small bumps, resembling a toad's skin, or piece of same used on sword handles. It looks like the iron has been heated to a very high temperature and started to boil, before quenching. The surface has a shine to it, unlike corrosion and I don't think it has been lacquered or given a thin coat of polyurethane. I can find no similar examples in books or sales catalogues. The tsuba has a simple , symmetrical, pierced design, possibly of four axe heads in negative silhouette, or four circles in positive silhouette around a central circle. The hitsu ana is plugged, probably with lead, or possibly a tarnished silver metal (pewter or silver). Overall, the tsuba is large, indicating that it is old (before 1550?). The plate is not flat, but convex on both sides a shape is known as go-ishi gata (go stone shape) and appears skillfully executed as the convex surfaces are very even. Height: 9.2 cm, Width:9.2 cm, Thickness at rim: 0.2 cm, Thickness at Seppa Dai: 0.5 cm. Thanks for any information you can give me, John