JohnTo

Gold Tier-

Posts

283 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

1

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by JohnTo

-

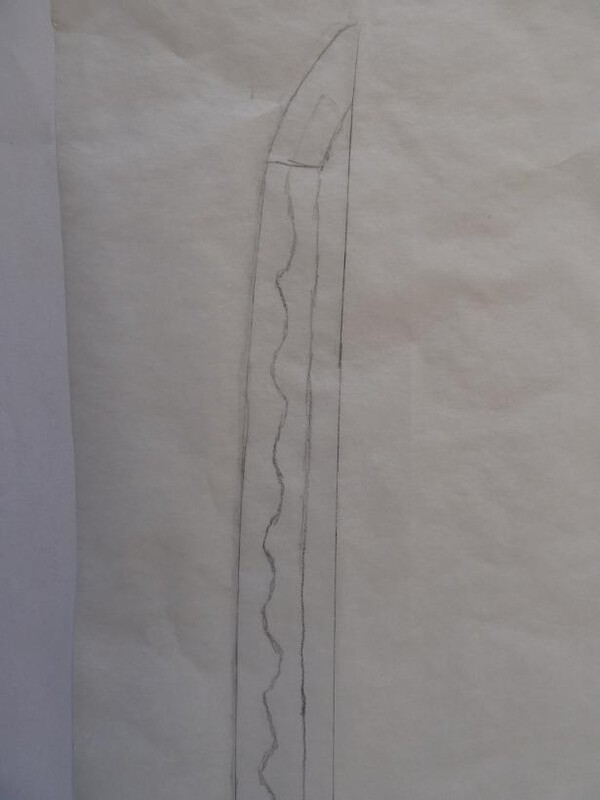

I thought that I would share my observations of these two 19thC iron tsuba as they share a lot in common and possibly typify the way that sukashi tsuba were developing at this time (comments?). The other tsuba is posted separately (Sukashi Tsuba #2: Mantis and Wheel). Both tsuba are essentially circular (7-7.5 cm diameter) with a D-shaped profile to the outer rim. Both seem to have been cut from a flat plate with simple, largely open sukashi designs, parts of which have been carved below the plate surface to produce three-dimensional effects. The design of the first tsuba based upon three pieces of horse riding equipment, namely a saddle, crop and bit, plus a single bird linking the crop to the rim. First Questions: The use of birds to link and strengthen different parts of sukashi tsuba is common, even though it often appears to have nothing to do with the overall design. Why not use straight bits, circles or S-shapes? Any reason why a simplified bird is used? I’ve sometimes seen them called chidori (sparrows) and sometimes geese, but they look generic to me. Is the use more prevalent amongst certain schools? When I first got this tsuba I thought that the cross within a circle was the Shimadzu family crest, or perhaps some Christian symbolism. I realised that in fact it is one side of a bit used in a horse’s mouth, the middle part (the chain link) appears at the top of the tsuba and the other side is missing from the design. Perhaps the separation of the parts of the bit is deliberate and is in fact a secret way of alluding to Christian leanings of the owner. One of the features that I like about this tsuba is the difference in sukashi carving. The cross within a circle is a simple two dimensional design, i.e. flat across the face. The crop and chain are more rounded and the change to a three dimensional design is completed with the saddle, which is skilfully shaped. To my mind, this makes the design more interesting than the essentially flat (two dimensional) designs commonly found on Kyo and Akasaka works. The tsuba is signed Hidemitsu (possibly read as Shumitsu) but I can’t find a Hidemitsu in Markus Sesko’s genealogy charts or elsewhere. So, Question 2: Any information regarding the artist or school? The tsuba is oval (7.4 cm high by 7.0 cm and 0.5cm thick) with a D-shaped rim, the outer edge being rounded. Overall the tsuba is in good condition with small areas of red surface rust on an otherwise dark, purplish black patina. The rim is essentially smooth with some small (1 mm) lumps which may be due to tekotsu rather than corrosion. Based on the carving within the rim I’d go for Bushu, Higo, Shoami or possibly Kinai schools, all of which seem to have produced open sukashi tsuba with carved designs. But then I wonder if travel within 19thC Japan was so commonplace that tsuba artist were pretty fluid as to where and for whom they worked, so that schools lost much of their identities. I’ve seen several riding equipment tsuba at auctions over the years and have added this Owari tsuba from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, which shows some similarities in the design but the forging appears totally different (Word document). Regards, John (Just a guy making observations and hopefully learning by asking questions) OWARI TSUBA FROM BOSTON MUSEUM.docx

-

- 1

-

-

Thanks Jim for your version of narihira's departure from Kyoto poem. Michin Curran. Ive seen Jim Gilbert's Kyo sukashi tsuba on the link on this website. The two tsuba are essentially identical but in mine the birds are flying upwards, in Jim's they are flying downwards. Its impossible to tell if they were made by the same guy, but I like to think so and that one morning he thought 'I'm bored. Kow what, today I will make the birds will fly the other way' john

-

Thanks guys for putting me straight regarding the lost wax moulding process vs the actual way menuki are made. I'm not a pratical metal worker, just someone who observes and makes comments on their observations. Menuki don't have a particular interest to me, I much prefer tsuba. When I ran a science group I would often say (when I was wrong) 'A c$%p theory is better than no theory at all' regards, John

-

Thanks Steve for the information. I’m familiar with Ariwara no Narihira (825-880) composing a poem at the 8-plank bridge (yatsuhashi) at the iris marshes of Mikawa at the time of his banishment from Kyoto I have a Kyo sukashi tsuba from the Goodman collection depicting this incident (described in the catalogue as banners flying in the wind), which I love very much (see Pics). There are lots of different versions of this tsuba, some just the bridge (my version), some just the irises, some with both. I guess that is what I love about tsuba, being able to find out what the theme is, especially when it is wrongly catalogued at auction. I have not been able to find the definitive poem that Ariwara no Narihira composed at the bridge that expressed his wish to return someday to Kyoto. One quoted example was: 殻衣きつつなれにしつましあればはるばるきぬるたぼをしぞ思ふ。 Karakoromo kitsutsu narenishitsumashi arebaharubaru kinurutabi oshizo omofu. A Chinese robe I have worn so often, I know it as I do my wife. Having come so far, this journey rests heavy on my thoughts. Reading that his banishment had something to do with his numerous dalliances with the ladies of the court I find it hard to believe that he should write a poem about his wife, or is he just missing his Chinese robe? Regards, John

-

I hope you have not maligned the Aoi, they may both be genuine and have been made by the lost wax process, which has been used since the bronze age. I recently went to the V&A museum in London where they had a video showing the casting of a complex bronze figure using this process. I have no knowledge of how Japanese tosogu artisans worked, but the process was common in China. So here goes my description of the possible process of making a simple shaped menuki. First step is to get hold of a suitable modelling material. Clay or wax is often used in the west, but ivory offcuts from the netsuke makers would be ideal. Glue the ivory to a metal or ceramic plate and carve out the face side of the menuki. Cover the finished carving with a releasing agent and pour on plaster of Paris to make a mould. Slip a knife under the metal/ceramic plate to free the mould. Pour a small amount of wax into the mould and swill round until the inside surface of the mould is coated. Repeat until the wax layer is of the correct thickness. A bit like making a chocolate Easter egg. Place small pieces of wood (matchsticks) at either end of the open side of the mould. Press any metal grips sometimes found on the inside of menuki into the wax. Fill the open mould with more plaster of Paris to make a single lump with the bits of wood sticking out. Once dry, remove the bits of wood, place the completed mould upright and heat until all the wax has run out. Pour in the molten metal of choice then smash the mould to free the menuki. Cut off the metal from the casting hole and finish of the menuki as desired (guilding, engraving, inlay, etc). The making of plaster of Paris moulds can then be repeated many times. Of course, if the original carving becomes damaged the flaws will show up in all subsequent moulds and subsequent castings. I ask the question ‘Why would a menuki maker not use this simple method for an object which has no complex undercutting?’ These guys had to make a living. Although they may have used the same mould they could probably vary the metals used as well as the finishes. The original carving would have been thrown away once it had started to deteriorate. In my opinion, the average tosogu was not in the habit of making one-offs. I have an iron sukashi tsuba which is an exact duplicate of one the NY Met. As theirs was bought in 1946, I doubt if mine is a later forgery, just a second example of a successful design used by the maker (I’ll probably post it later). Most bronze artists make multiple castings of their sculptures then destroy the original clay model. Did you know that there about 28 bronze castings of Rodin’s ‘The Thinker’ not considered fakes. Best regards, John

-

You can heat the tsuba in a steam of dry hydrogen. A heavily rusted viking sword was treated this way to reveal fine brass inlay (like a Heianjo tsuba). Not a prcoess for the amateur collector though. regards, John Corrosion and metal artifacts - a dialogue between ... - NIST Page nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/Legacy/SP/nbsspecialpublication479.pdf CONSERVATION OF RUSTY IRON OBJECTS BY HYDROGEN REDUCTION. L. Barkman. 155 ...... Figure 4a. Hilt of a viking sword before hydrogen reduction ...

-

Unfortunately fakes abound in all areas of art. Once a certain object passes a price threshold the fakers move in, as they have for a 1000 years (Stowe school Yasutsuna tachi, Chinese ceramics). In our field of Japanese swords and tosugu the signatures of many famous artisans are doubful. Omori Teruhide, and Kano Natsuo must have been producing about 10 tsuba a day, if you go by signatures. With modern equipment and the limited knowledge that we collectors have with authentic pieces (how many of us have more than 10 good pieces in our collections?), the problem will get worse. Thanks for the reminder and warning. John

-

Can anyone help regarding the signature maker of this Omori style fuchi/kashira? I bought this at a London auction back in 1975 and the signature was listed as Matsushitatei. As the signature is in a flowing script I have had trouble confirming this. I’m OK with the kanji for Matsu and Shita, but I have never found anything looking like the third kanji for Tei in any reference book. The design of the fuchi/kashira is the classic Omori waves in shibuichi with highlights picked out in gold. It is very similar to a larger example sold in the RB Caldwell collection, Sotheby’s 30 March, 1994, Lot 327 and signed Omori Teruhide. I thus conclude that my fuchi/kashira was copied from a Teruhide design and must be one of the few copies of this type of work not actually inscribed ‘Teruhide’. Matsushitatei, or a name like this, does not appear in the Omori school genealogy chart (Genealogies of Japanese tsuba and toso-kinko artists, Markus Sesko). Of course Japanese artisans often changed their names several times in their careers, so he may be listed under a different name. The only reference I can find to Matsushitatei is a mumei menuki with NBTHK Hozon paper attributing the work to ‘Goto Kenjyo (1586-1663), Matsushitatei school’. However, his dates would probably be too early for this design (Omori Teruhide’s dates are 1730-1798). Besides, there appears to be no link between the Goto school and this mysterious Matsushitatei school. Can anyone provide information about this not-readily documented artist or school? Best regards, John

-

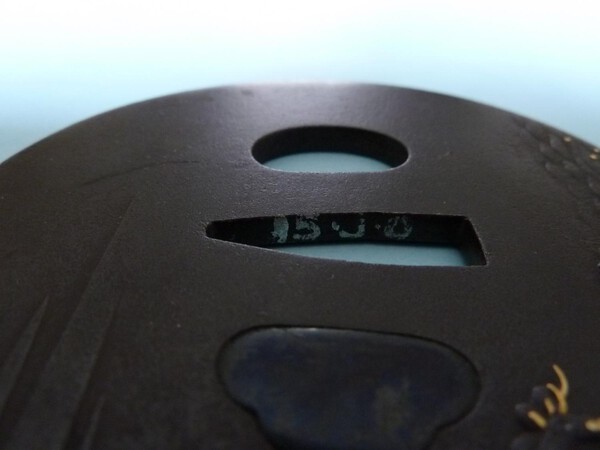

I would welcome some comments regarding this tsuba. Essentially, it is a standard mumei maru gata iron tsuba with a brown patina, the iron plate is carved in slightly high relief and inlaid with gold and shakudo figures. The kogai hitsu is plugged with shakudo and it was probably made in the 19th C. What I find interesting about this tsuba is the subject matter. It is a landscape depicting a nobleman gazing at Mount Fuji, while a (lady) attendant kneels beside him holding his sword. The figures are comprised of gold, shakudo and silver. Mount Fuji is carved in low relief and the cap is inlaid with silver to depict the snow. The figures are standing by the shore of a lake/ocean with waves lapping the shore and highlighted in gold (a subdued Omori style). A pine tree is carved in positive relief and also highlighted in gold. The reverse shows a similar scene without the figures or Mount Fuji and a twisted older tree, perhaps the same one to depict the passage of time on the original scene. I have found a tsuba with the same subject in the Church Collection at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, UK (http://jameelcentre.ashmolean.org/object/EAX.10987) see below. However, this tsuba is based on an ishime shakudo plate, rather than iron and the reverse (not shown on-line) is reported to show a charcoal burner’s hut. In my opinion, the depiction of the tree and Mount Fuji are not as good as my tsuba. The tree looks like a simple copper twig and Mount Fuji is flat topped and lacks the characteristic triple peak. However, the Ashmolean museum has attributed their tsuba as being in the style of Shummei Hōgen (i.e. Kono Haruaki 1787-1860). Personally, I would have thought that the simple depiction of the tree and Mount Fuji was not of the standard expected of his school. I’m not saying that my tsuba was made by the same hand, but the unusual subject matter indicates that it probably came from a common book of designs and hence the same workshop. I’m not sure if Kono Haruaki produced any works in iron, I’ve only come across soft metal, signed examples. A lot of 19th C tsuba makers seem to have made iron tsuba with mixed metal inlay, including the Goto, so I would not really like to hazard a guess as to the maker, or school. The subject matter makes me wonder who it was made for. I’m speculating that it was made for a daimyo, or some other court official. There is a slight change in texture of the iron around the seppa dai area indicating that it was once mounted on a sword. The reason I think that it may have belonged to a daimyo is the question ‘Why would a lower grade samurai wear a tsuba that depicts his lord apparently idling his day away, while some poor attendant has to kneel patiently by his side’? Some might think that the scene flatters the ascetic qualities of the nobleman, but I believe that, if worn by a lower rank samurai, the subject could be interpreted more as a satirical comment. The last thing any samurai would want to do would be to cause offence to his superiors! It may have been made for sale to a western collector (it has an old collector’s number on the inside of the nagako ana). However, in order to be made saleable to a westerner I imagine that it would be signed, even if gimei. So apart from the usual requests for information regarding maker and school, any comment on the subject matter? One final thought. I have included a photo of the collector’s number on the nagako ana. There may be someone out there who is trying to collate information regarding these. Best regards, John (just a guy asking questions and trying to learn) Church Collection tsuba is attached below in a Word document. church collection tsuba.docx

-

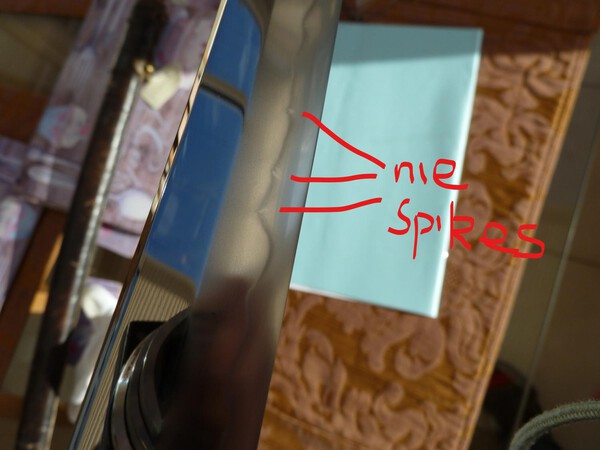

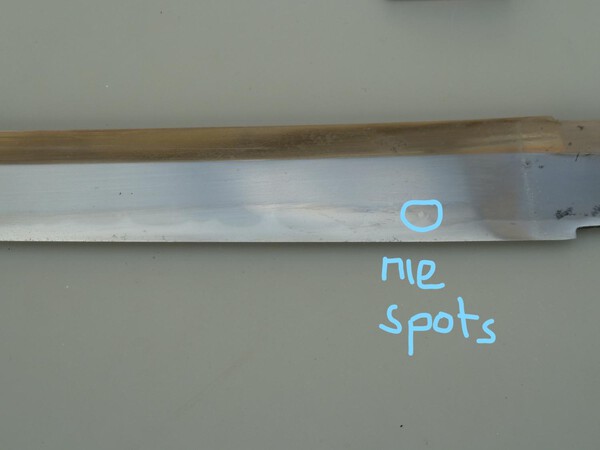

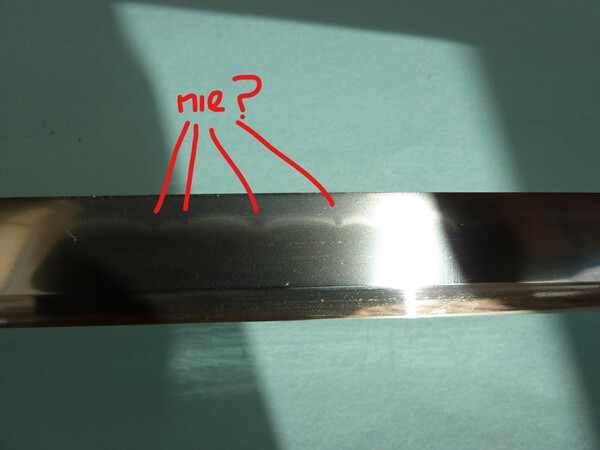

I’m rather disappointed with the level of comments posted so far, which seem to regard any non-Yasukuni gendaito as a piece of old iron from the railway in Manchuria that has been oil quenched and acid etched. I think that I made it clear from the outset of this posting that the Yoshimichi blade was a Seki arsenal gendaito and not a blade worthy of Juyo rating. If you read carefully I said that the ‘nie’ and ‘sunagashi’ were not the classical type found in older blades. I was hoping for some scholarly information that might spread some light on the correct terms to use with arsenal blades and how they achieved the effects seen in the hamon of this blade. Books like Fuller and Gregory’s ‘Military Swords of Japan 1868-1945’ deal mainly with the koshirai and markings found on gendaito. Kishida’s ‘The Yasukuni Swords’ deal with blades made in the traditional way. Kapp and Yoshihara’s ‘Modern Japanese Swords and Swordsmiths’ is the only book I have seen with detailed description of the practices in the Seki workshops. They maintain that although the majority of blades were made from ‘railway lines’, or namban tetsu as it was called in Shinto times, they were forged and water quenched. Many people do not regard blades made with anything other than tamahagane as real Nihonto, so if anyone out there has a worthless Yasutsugu made with namban testsu, preferably with a Juyo Bunkazai rating, I’ll be pleased to buy it from them, but at a greatly reduced price! There seems to be little detailed information regarding the manufacture and features found in arsenal gendaito. This is a shame as these blades are now being sold for upwards of £1000 and many Notice Board readers will never be able to aspire to owning anything other than gendaito due to financial constraints. My own guess is that a range of forging techniques were used in gendaito, ranging from the Yasukuni shrine blades down to the machine made blades with serial numbers stamped on them. I expect that all the smiths that worked in these forges are now dead, but hopefully someone (at the NBTHK) recorded their experiences before they died and will someday, soon, publish a book. Many gendaito are signed and I find it difficult to believe that a Japanese craftsman would bother to sign his work if he regarded it as a piece of junk. Is their work really inferior to many of the swords (mainly mumei) produced during the late Koto period (civil war) or late Shinto (low demand and poverty) when conditions were not favourable to the production of fine blades? Understandably, many Japanese would like to forget their recent military past, plus, I believe, swords from that era are still banned in Japan. Therefore, a Japanese collector is likely to see more Koto blades than gendaito, the reverse of what we see in the west. As for my Yoshimichi, I believe that it a folded piece of railway line (fine masame hada) which was water quenched to produce a nioi based hamon. There are bright flashes which look like nie, but as I said originally, they are outside the normal range of what nie looks like. Surely the Japanese must have a name for them. I have reposted the photo of these as I posted the original one without a legend pointing out the ‘nie’. Paul, yes, I do know what ‘real’ nie, sunagashi, inazuma etc look like. To illustrate this I attach a couple of photos of blades in my small collection. The first is a modern blade, dated 1980 and inscribed ‘ustsushi Kiyomaro, Minamoto Moriyoshi’. Without a shinsa I would not claim it to be by the mukansa smith Tanigawa Moriyoshi (1920-1990), it might be a copy of a Moriyoshi copying a Kiyomaro copying a 14thC sword, but it is typical of his style, a large Nambokucho style piece. It has sunagashi and more inazuma/kinsugi flashes than a thunder storm in summer. I had the pleasure in examining the Kiyomaro (Masayuki) of Field Marshal Festing when it came up for sale in 1993, the inazuma on his blade almost had thunder as well as lightning, this blade is quieter interpretation of Kiyomaro’s work. The second blade has been shortened but has a NBTHK Tokubetsu Kicho attribution to Midzuta Kunishige. It is crammed with nie based activity, including long patches of sunagashi along the length of the blade which ends up as a kaen boshi. All the best, John

-

I have just posted some questions regarding a Yoshimichi Gendaito. Mine is just signed Yoshimichi, photo attached.

-

The second Gendaito I would like information on is signed Yoshimichi. Much as I would like own just about every sword that I see for sale, financial constraints force me to be selective. Usually I pass over Gendaito that I see at auctions but I bought this one last year as it appeared for sale about the time of a special birthday, looked interesting and was in perfect polish, thus obviating the need for an expensive repolish costing more than the sword itself. Besides, I was short on funds, but my wife said ‘Yes’. The first interesting feature is the koshirai. Cheap leather bound wood saya and civilian tsuba/fuchi/kashira (see Military Sords of Japan 1868-1945, Fuller and Gregory, plate 63, a). The unusual feature about the koshirai is that the same is black. Anyone know the reason for this? The blade is a standard shinogi tsukuri construction and is signed Yoshimichi and has no arsenal mark. Could the lack of arsenal mark indicate that this was a civilian commission (see koshirai)? The smith is probably the same Yoshimichi in the Seki Tanrensho listed by Dr Jinsoo Kim but the kanji for ‘michi’ differs in execution from the example he gives (which if either is genuine? The difference may just due to a change in signature over the working life of the smith; my personal signature has changed a lot over the years). The blade has a medium width gunome midare hamon and the jihada appears to be a fine tight linear masame (industrial steel rather than tamahagane?). As with my other Seki blade (see posting for Seki Ju Fukuda Sukemitsu), the hamon is nioi deki and the peaks in the hamon contain 1mm bright ‘nie’ particles just inside the nioi line. On one side of the blade (ura for katana) a single peak extends beyond the shinogi and with a bright area inside the ha about 4mm in diameter. OK, that’s the general description, now for the details and queries. Hopefully the photos of the Yoshimichi show these features, but I had a lot of trouble taking them over several weeks under different lighting conditions. What is clearly visible by eye was difficult to capture on film. At first sight the hamon looks like a typical nioi deki, but looking closely it actually has three distinct bands. The outer band (nearest the shinogi and hamon) is a white band of nioi about 1 mm thick. Adjoining this is a dark (black) coloured band also about 1 mm thick. Below this is a feint white band with ashi extending below the tani of the gunome hamon. The dark band widens in the tani and forms fine black sunagashi striations as it interacts with the masame jihada (see Q3). The three bands extend along the whole length of the blade, on both sides. I’m used to seeing a dark area above a white hamon, where the polisher has extended the outline of the ha and darkened the ji, but not the other way round. I also have a Meiji period tanto made for the tourist market, in good polish, which shows a similar effect. In this case the hamon is a regular gunome, but the dark and light bands are coincident, i.e. just one band, the colour changing as the blade is rotated in the light (note: the ashi band on this sword can also appear white or black, depending upon the lighting, see photo). A few months after buying the Yoshimichi another Seki Gendaito came up for sale, reportedly signed Nagamura Kiyonobu, with a medium width togari gunome hamon. It was not in such good polish as my sword and appeared muji. Although not so distinct, the hamon appeared to be the same three band construction as my Yoshimichi and also had the contrived nie particles (see below). Is this the result of a polishing style or forging technique characteristic of the Seki forge? I suppose the three band effect could be produced by painting on a coating to protect parts of the hamon during polishing, but this seems too complex a process for a sword produced under (presumably) wartime conditions. The only explanation that I can come up with for the dark band is that there is a gradation of size in the martensite crystals across the hamon, the larger ones nearest the ha. They were all given a black patination of magnetite (like some tsuba) which was then preferentially removed from the smaller nioi in the final polishing, leaving the usual white nioi hamon on the outside. Maybe completely wrong, but as I used to say when working in a research lab ‘A cr#p idea is better than no idea at all.’ I hesitate to call the dark striations seen in the tani of the gunome hamon ‘sunagashi’, as the particles are only just visible to the naked eye and black. They are probably darkened steel at the interfaces of the layers in the masame. Hakikake (sweeping) seems a better description, but nearly all the books that I have only describe hakikake in relation to the boshi. Nagayama also describes hakikake as a feature on the main part of the blade, but his pictures show this to be on the ji side of the hamon (The Connoisseur’s Book of Japanese Swords, p 100 &118). So what are they called? The nioi hamon contains the same type of ‘nie’ spikes seen in my Seki Sukemitsu blade (see Sukemitsu post), but this time they often appear in pairs at the apex (yakigashira) of the peaks. Again, they also appear to be open at the bottom in many cases, but this may be a result of the polishing. The placing of these ‘nie’ spikes is deliberate, which is why I hesitate to call them nie, besides, I have no way to determine if they are the same martensitic material of true nie. That makes three Seki blades where I have seen this type of nie. Is this a feature of the Seki arsenal forge and is there a special term to describe these? Although the gunome hamon is fairly regular, on one side the swordsmith has created a single peak which extends beyond the shinogi. Quite an attractive show of exuberance. A similar peak appears on the other side, but not so large, remaining below the shinogi. Inside this peak is a large ‘nie’, a bright tempered area about 4 mm in diameter. Seems a bit big even for ara nie! Nagayama defines mura (“uneven”) nie as ‘an irregular particle much larger than other nie, which partially intrudes upon the hamon’. Is that what this should be called, because it sure is ‘much larger than other nie’? Similar, but much smaller ‘nie’ particles (1-2 mm) can be seen inside the yakigashira of the larger peaks in the hamon on my Sukemitsu blade (see other post). I have other swords where I’m happy identifying nie, nioi, sunagashi, inazuma, tobiyaki, mune aki, etc, but I find the exact terminology to describe the metallurgy in these two gendaito a problem. Amazing how after all these years that naming of features in an inhomogeneous piece of steel can still present challenges.

-

I’m putting on two posts requesting further information regarding features in two Seki arsenal blades, the first by Fukuda Sukemitsu (this post) and the other by Yoshimichi (see other post). There are several features in these blades which I feel lie outside, or at the fringes, of classical definitions and seek clarification. I bought the Sukemitsu back in 1973 and it represented the first katana in my collection. I had become interested in Japanese swords more than 10 years earlier and had manged to purchase a rather tired koto wakizashi out of my schoolboy pocket money. A girl and marriage reduced my spare cash until I bought this sword from a friend. I was over the moon with it at the time as it had everything that I expected in a Japanese sword, namely a blade in good polish, recognisable hamon, signature and traditional mounts. As time went on, and experience grew, I began to realize it was not as good as I first thought. The blade is signed Seki ju Fukuda Sukemitsu and has what I later found out to be a Seki arsenal stamp. The odd thing about the sword is that it had been mounted with old koshirai (tosho tsuba, Mino Goto fuchi/kashira etc.). Probably the sword was remounted as an iaito in the UK, but remember prior to 1973 cheap Japanese swords were still readily available, but spare parts (kurikata etc.) were not. However, I digress. I have recently started to catalogue and describe my collection and have found some features of the Seki blades which don’t quite match up with similar features in pre-Meiji blades, e.g. nie. I know I’m being pedantic, but that’s what collecting is about. So I welcome comments and help. The blade is a typical WWII gendaito, shinogi tsukuri construction with a muji (or overcleaned) hada and a shallow sanbon sugi hamon of nioi incorporating spots of ‘nie’. The sanbon sugi consist of a repetitive pattern of two small peaks and a third larger peak (see poor photos and oshigata type drawings). The questions that the hamon raises are as follows: The smaller peaks in the hamon often show pointed ‘nie’ thrusting upwards into the nioi. The bottom of these ‘nie’ particles are usually open, fading away into the ha. They are also seen in the Yoshimichi blade (better photos). They are bright shiny flashes that look like nie, but I hesitate to call them that as they lack randomness in their placing. I assume that the smith removed a speck of clay at the apex of the peaks before yaki-ire to form these (martensite?) features. Are they nie and is there a specific name for them? Are they a feature of Seki arsenal blades? The larger peaks often have a bright circular ‘nie’ particle of about 1 -2mm in diameter near the tip. However, on some of these peaks part of the hamon breaks away forming two types of isolates spots (Questions 3 and 4 below) The first type of spot is a bright shiny centre surrounded by nioi. As the spot is free from the hamon I am happy to call this tobiyaki (though not quite like the classic tobiyaki seen some of my older blades). The second type of spot only consists of nioi. I would have called this yubashiri, but Nagayama (The Connoisseurs Book of Japanese Swords) defines yubashiri as a ‘collection of nie within the ji’. As there is no nie, are the spots still yubashiri (I would have thought so)? Sorry about the quality of the photos, taken after many attempts (see posting for Yoshimichi for better examples).

-

Nice Shinsakuto W/ Horimano For Sale :)

JohnTo replied to Salvatori Moretto's topic in For Sale or Trade

Brian said You mention it is a shinsakuto. He doesn't mention age or who made it at all on the auction. It can't be an unsigned shinsakuto according to law there. I remember someone coming back from Japan after studying kendo and iaido with an unsigned shinsakuto. The smith did not sign it as it was made in addition to his quota. Just have to know the right people I guess. -

Brian/Ford Thanks for the info. I think you are right The band of rust and magnetite crud in the piercings was saying ‘Genuine’, but the patina and lack of corrosion was shouting ‘Wrong’. While puzzling over this tsuba I had a break to make a cup of tea and as I fished the tea bag out of the cup with an old stainless steel spoon there was a similar patina staring at me. The spoon had acquired a blue colouration from the dishwasher. Hence my wondering if it was a type of stainless steel, rather than wondering if samurai used dishwashers to clean their tsuba. I was also concerned about the complete lack of any evidence of corrosion (rust or pitting) on the main body. As the old saying goes ‘If it looks too good to be true, it probably isn’t’. This tsuba was different and probably had a uniformly black patina originally, which I guess had become worn through in places (based upon limited observations in my collection, black patination does seem subject to wearing away in places). A previous owner probably cleaned it with acid to remove the patina, using a cloth rather than soaking, which only removed the patina from the high points. He probably attempted to restore the patina by tempering (hence the multi coloured effect). Maybe he should have invested in a can of gun blue. I came across some (once) nice Kyo sukashi tsuba at an auction about 10 years ago. They had obviously been soaked in a commercial (phosphoric?) acid cleaner and rust proofing agent that gave them a dull grey colour and still left the pitting. I was outbid and the price they went for indicated that the buyer thought they were restorable. I suppose I could have the tsuba repatinated professionally, but to be honest, I quite like the effect. The remaining black patination in the indentations and sunken carvings has produced a pleasing 3-D effect which may be lost with a uniform black colouration

-

Happy New year I have recently bought an iron sukashi tsuba with an unusual patina that I would like some opinions on (see three photos). The tsuba is wakizashi size (6.3 cm, 5.7 cm 0.6cm) and nicely carved in the round and pierced with a pine tree design. The nagako ana has scratches from a sword and punch marks indicating that this was once mounted, though the punch marks are often found on late tsuba purely as a form of decoration. The tsuba is unsigned and my initial guess was that it is 19th C Bushu or Echizen work. However, probably it is a cast piece that has been finished off by hand as the form is similar to a 19thC cast and carved brass tsuba that I have (see photo of my example and see an identical tsuba on Ebay [Matsukage, Dec 2016]). The unusual feature of this tsuba is the patina, which is outside my experience. It resembles a piece of silver which has blackened with age but has been regularly cleaned with a cloth, resulting in discolouration only on the inner surfaces. However it’s not silver, it is iron and magnetic (always good to check, I recently bought tsuba from a major auction house that was described as ‘bronze’ but was magnetic). Nor does it appear to be a case where the tsuba originally had a black patina which has worn away through use. The effect is uniform over all the surfaces. The piercings looked a little clogged and so I cleaned them out with a wooden tooth pick. The black specks that were removed were also magnetic (probably magnetite, Fe3O4), possibly indicating that the maker had been a bit sloppy in removing all the scale. The iron has no other traces of rust, except for bands of surface rust running along the mid sections of the piercings. The tsuba looks as if it could have been made yesterday, but was part of a job lot of 8 iron and soft metal tsuba plus fuchi-kashira and menuki that I bought at an auction. The lot looked like someone’s collection of better than average pieces from 17th-19thC. Looking closely, the shiny parts the steel shows a slight surface colouration that includes purple, steel blue, bottle green and copper red. The sort of effect seen in tempered or partially blued steel. I think that the patina is deliberate and original. Normally I would be overjoyed at finding an iron tsuba in such pristine condition, but as it appears to have been on a sword I would have expected some evidence of corrosion, especially on the metal with minimal patination. I have thought of the following possible reasons. Comments please. The tsuba is 19thC cast steel and subsequently carved and engraved by hand. Any original black patina was deliberately polished off the outer surfaces to produce the effect seen today, possibly augmented by tempering at the final stage. Subsequent owners of the tsuba treated it with great care and hence prevented corrosion. The tsuba is 19thC as reason 1, but was made of a non-corroding iron/steel. Proper stainless steel, with at least 10.5% chromium, was not invented until 1911. However, Stoddard and Farraday in about 1820, noticed that low chromium iron alloys were less liable to acid attack. Perhaps some enterprising Japanese tsuba maker was experimenting with new iron alloys from Europe or the USA? Apparently 0.1-0.4% copper, or 10-20% nickel, also improve the corrosion resistance of steel. Unfortunately, I do not have access to a X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer (unlike Ford Hallam) and hence cannot determine if other metals are present. Nor am I going to wrap the tsuba in a cloth soaked with saline and leave it for a month to see if it really is corrosion resistant. The tsuba was made in the early 20thC out of stainless steel, or some such alloy, possibly for use on a gendaito in a moist environment, e.g. jungle. It’s a completely modern tsuba that the previous owner of the collection picked up somewhere, simply because he liked it. Best Regards, John

-

The question has arisen as to why the polisher completed his (no doubt) expensive work on a blade with hagire. Made me wonder if the hagire developed after polishing. My reasoning for this is as follows. Much of the curvature on a Japanese sword occurs during yaki-ire when the mune shrinks more than the ha, resulting in a blade where the edge is in a state of tension. Hagire can develop during quenching when imperfections in the steel result in the tension pulling the steel apart. In this case the flaw may have not been sufficient to have resulted in hagire. However, during polishing, steel is removed from the ha, thus increasing the tensile load. Polishing also involves water, the great enemy of steel. Perhaps water seeped into minor flaws or spaces between the (martensite) steel grains during polishing, causing some corrosion within the steel after the polishing process had ended. The tensile loading in the ha, always present, may have caused the small flaw to increase, until catastrophic failure, metal fatigue, resulting in hagire. Rather like a car windscreen, where a small scratch can sometimes cause the windscreen to shatter months after the initial damage. Just a thought, John

-

Whenever I see a tsuba of this form (mokku shape, lightly hammered surface, mixed metal design in lower right quadrant, usually wakizashi size) in auctions they seem to be catalogued as Tanaka school. Not that the Tanaka school only produced tsuba in this style. What interests me is that, on the reverse, the decoration often appears to be a couple of small rocks lying on the ground (as this example) or a small plant in the lower left quadrant. Always seem to be a bit odd and nothing to do with the main subject. It appears that the artist was happy with the main theme and then just stuck something simple on the back. Any ideas why they should choose rocks?

-

I have a tosho tsuba with a couple of the same shape piercings. It was ex-R B Caldwell collection (Sotherby's march 1994, lot 14), see attached. The piercings were described as carpenter's squares, but I don't know what the curved ones represent. The tsuba is in good condition and the surface still shows fine crossed hatched file marks that the smith used to finish the tsuba. I've often puzzled as to what the shapes represent.

-

Ken, Thanks for the info regarding the silver coating. The product does not appear to be available in the UK, but I have found a similar one. John

-

Ian, Thanks for the comment. On my tanto fittings the chrysanthemums look firmly attached, but at each end of the tanto there are silver braches with gold flowers. These are not attached very well and the ends of the braches are free from the main body of the fitting and have obviously been applied with little thought to practicality (they keep snagging the bag it is kept in). I did see similar fittings on a sword at a London auction (Bonhams, I think) a couple of years ago. I'm sure you are right that at the end of the 19th C pretty little tanto were being put together for tourists incorporating a variety of skills which would not usually be seen on products for the samurai market. Bonhams (New York, Sept15) have a couple of Meiji tanto with cloisonne mounts (lots 3342, 3343). They don't bother showing the blades and one is just described as 'containing a tanto blade'. Down here in South West England I have seen a couple of such tanto coming up at our local auctions, possibly from the families of the original owners. Unfortunately, we cannot all afford Juyo rated items at the big auction houses and have to bid on what comes up locally. John B

-

Can anyone help with the identification of the swordsmith (Akikane) who made this Meiji period tanto? The blade (8.0 inch, 20.3 cm) is kanmuri otoshi in form with naginata style hi cut into the lower half of the blade. The hamon is togari ba in nioi with small patches of ko-nie in the tani. The jihada appears to be muji or possibly a tight masame (the apparent feint masame grain may be due to the polishing plus minute rust specs). The nakago is roughly shaped with a kenkyo tip and the yasurime are sujikai (sloping downwards from front to back) and seems to have been signed in a hurry (Akikane, see photo). This seems indicative of a smith in the Meiji period being told to produce an attractive blade for an uncritical foreign tourist clientele who would probably not appreciate the finer qualities of Japanese blades, but having spent a considerable effort in producing a complex shape was still proud enough of his work to sign it. So far, I have been able to identify a smith of this era with this signature. There do appear to be other smiths with the name Akikane in the literature, but use an alternative kanji for Kane (Gendaito smiths AK144, AK145 and AK146) The koshirai appear to be typical of pieces aimed at the tourist market in the Meiji period, rather exuberant, but demonstrating the skills of the metalworkers, who were made redundant after the wearing of swords was banned in 1876 (just because these kinko artists no longer made items for the samurai did not mean that they did not turn out some superb soft metal works of art, e.g. the bronzes coming out of Miyao Eisuke’s workshop in Yokohama). In this case the koshirai are based upon silver plate with embossed and engraved sparrows and branched of blossom, with touches of gilt finishing. The fuchi/kashira/kurikata etc are all matching in copper with a black (shakudo?) ishime finish embossed with silver chrysanthemums and gilt borders. None of the pieces of the koshirai are signed, but overall an attractive little tanto. In such pieces the blade was usually of secondary importance. Sometimes an old blade would be utilised but, at the other quality extreme, a simple blade would be made with an etched hamon. This blade seems to be contemporary with the fittings and the difficulty in polishing such a complex shape would indicate that the forging had some artistic merit over many other blades made for such pieces. The ‘Aki’ part of swordsmith’s names seems to have become common around the Meiji era. Kuihara Akihide’s father established the NihontoTanren Denshusho at Akasaka in Tokyo around 1893. Akihide’s teachers were Inagaki Masanori and Horii Taneaki. Akihide taught many Gendai smiths including Amada Akitsugu, Akimoto Akitomo and Miyairi Akihira. All of these smiths (and others from this densho) used the same character for Aki as this example. This, plus the associated koshirai would lead me to speculate that Akikane was working around 1890 in Tokyo, but I can find no reference to him anywhere. It’s quite probable that Akikane quit swordmaking around this time due to lack of demand, but he may also have continued working under a different name. Can anyone help? While we are on the subject of this particular tanto, can anyone give advice on stopping the silver of the koshirai tarnishing further without causing abrasive damage? Thanks, John

-

Thanks to everyone, the replies were very useful. So the reading of the location is likely to be Toshima. The different phonetics are always a problem with kanji. I know that even the simplest kanji (ichi for one) can be read in five different ways, plus additional slight variations, depending upon the context. Tegarayama Masashige was my second choice of school (well I would say that wouldn’t I?) but his works are described as having a ‘good deal of ashi on both sides’. I can’t see any, but they may have been polished away. I’m really impressed with the knowledge out there on the Nihonto Message board. It’s no wonder that when I see a poorly described Japanese sword item come up at some local auction I inevitably find myself bidding against someone on the phone who has also seen a potential bargain. There are no bargains anymore. This particular blade was described as a 20th C tanto, signed with two mounting holes. The ‘two mounting holes’ first got me interested. As an added bonus the fittings were interesting (see photos), a nambam tsuba and a shakudo nanako fuchi-kashira set with a minogame (sea-weed trailing turtle), signed/inscribed Furukawa Yoshinaga (I gather Sabei Yoshinaga studied under Goto Ryujo and was the most famous representative of the Furukawa line, thus making the signature suspect). Even the menuki are nice, shakudo horse fittings, so overall I was pleased with the package, despite paying over the maximum estimate.

-

Can anyone help me with a couple of queries regarding this wakizashi by Masatomo My translation of the signature (see photos) is: Bunshima (or Bujima etc.) Minamoto Masatomo Bunkwa hachinen nigatsu hi (a day in February 1811) My first question is what is the correct reading of the first two characters for the smith’s home location, ‘Bunshima’ and where is it in Japan? The first character in the signature appears to be #89 in the Robinson’s ‘The Arts of the Japanese Sword’ Appendix C list for the provinces as in Bu-zen and Bun-go in the Saikaido, Western Sea Circuit (Robinson’s #s 61 and 62 respectively). The second character is Jima, Shima (for an island) or To (On reading). However I cannot locate anywhere in Japan with the place name Bunshima, Bunjima, etc. Can anyone help here? The second question is can anyone help with information about the smith? The Nihonto Notice Board JSL index lists 3 swordsmiths named Masatomo, none of which use the same kanji for ‘Tomo’ or were working around 1811. The blade is 30.7 cm (12.1”) with a shallow tori sori (0.5cm) of standard shinogi zukuri construction. Although in good condition it has been overcleaned, but still shows the feint outline of the hamon (see photo of tracing), which I would describe as toran formed by a 2-3mm wide cloud of nie. There appears to be kinsuji and a tapering yakidashi at the base. There appears to be a ko-itame grain to the steel, but no trace on ashi in the hamon. Hopefully repolishing will reveal the hidden beauty in the steel. I would surmise that the blade has a strong Soshu influence based upon the Shinto smith Sukehiro, a style which I understand became popular at the start of the Shinsinto period. My guess is that the smith may have belonged to the Masahide school.

-

Thanks for the replies, especially from John L. I'm assuming that the references that John gave are from Haynes, which unfortunately I don't have. There was a comment about the design overflowing into the seppa dai. There are also decorative punch marks on the reverse, indicating that the nakago ana has been modified to fit a balde more tightly. I often see this in 19th C tsuba that were made as works of art and never intended to go on swords, even though they may have copper inserts and punch marks around the nakago ana. I assume that these were put on to enhance the feeling that the object is in fact a tsuba and not just a decorative piece of metal.