-

Posts

1,899 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

20

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Gakusee

-

Shinsa decisions….justification?

Gakusee replied to Matsunoki's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Hey Kiril, could you please specify if that kodachi was awarded a Juyo status? If so, firstly, congratulations and secondly - what was the Juyo judgement as to school / smith please. If I may, I would like to contrast it with the Kaga school you refer to in the NTHK comments. Thank you. -

Shinsa decisions….justification?

Gakusee replied to Matsunoki's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Colin, it might seem unfair but that is one of the charms and secrets as to why it is such a coveted rank. Firstly, Juyo swords by definition are the ones which deserve it / qualify for it on qualitative, aesthetic, historic grounds and secondly they are additionally swords which happen to excel (in their tradition, time period, smith, school etc) in their category and be superior to others in the same category. So, there are two sets of criteria: absolute and relative. Sometimes swords fail on the relative set of criteria, even though they might otherwise qualify on the absolute set. If someone analyses the published swords in the Zufu which passed in the unfortunate shinsa that disappointed someone, that someone then can probably deduce why his / her sword failed: it could be that his failed Hizento just was 5cm shorter than the ones that passed, or his failed Kagemitsu was gakumei but the one that passed was ubu and zaimei, or that there were too many submitted Bizento and they have their statistical distribution to adhere to (and hence have to pass some Yamato, some Shinto, some Gendaito) which obliterates his otherwise top-notch Yosozaemon Sukesada, etc etc. Sometimes, we feel deprived and cheated but that is how it is. If we do not like it, we can always choose not to submit. But if you play the game, it helps to have an understanding of how it works. -

Hi Georg Please do not give up. It might be that they did not reach a consensus this time or there was a superior Kiyomaro in the line-up. I have had instances where an item failed a particular shinsa and then, the following time I submitted it, it passed. It has happened to me with koshirae and also with swords. It is a great sword one way or another.

-

Hi Jacques, I thought it made it clear in my post that the wakizashi was more in Mino style and described by the Ministry as made when he moved to Mino? I talked about the wider hamon (cf what Honma sensei wrote) and the word “Noshu” in the mei. Also, referencing the zaimei tachi, I qualified it as a transitional blade. One cannot say “this blade does not look Soshu” on the basis of only oshigata, as Soshu hamon could take lots of shapes just the way Mino can (even though Mino is much more specific). If you are looking only at the hamon of that tachi, you cannot definitively say that it looks pure Mino either. In fact it looks less Mino than something else. With Soshu, it is much more about the colour, the purity (and wetness) of the steel, the elegance of jinie, the presence or not of chikei (and also size), the way sunagashi and kinsuji show up (more elegant than the cruder Mino work). As you move into later Soshu (Hiromitsu, Akihiro et al), the elegance is starting to dissipate and we see some gaudier work. But the problem is all of this needs to be seen in hand an and oshigata cannot render it adequately.

-

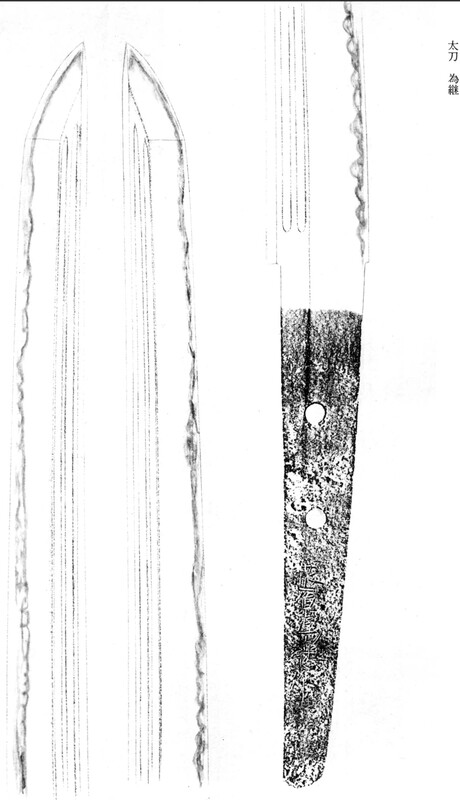

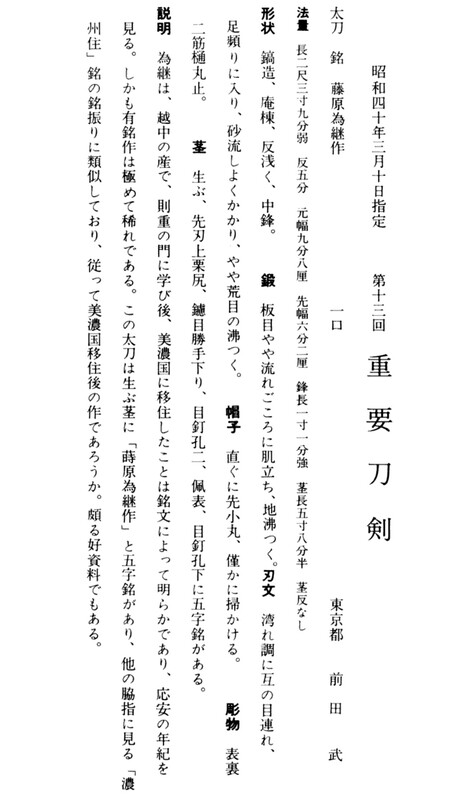

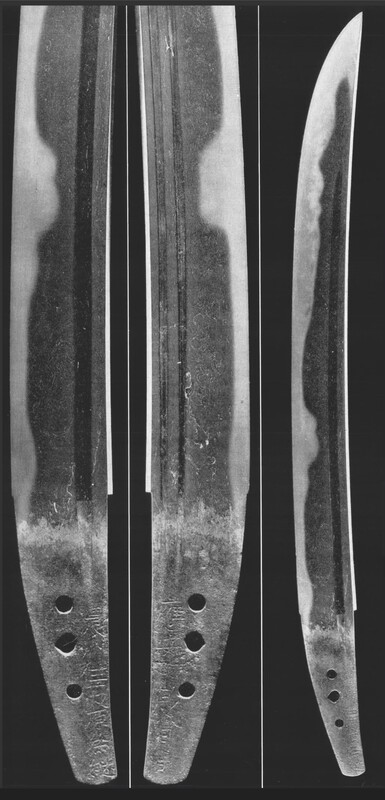

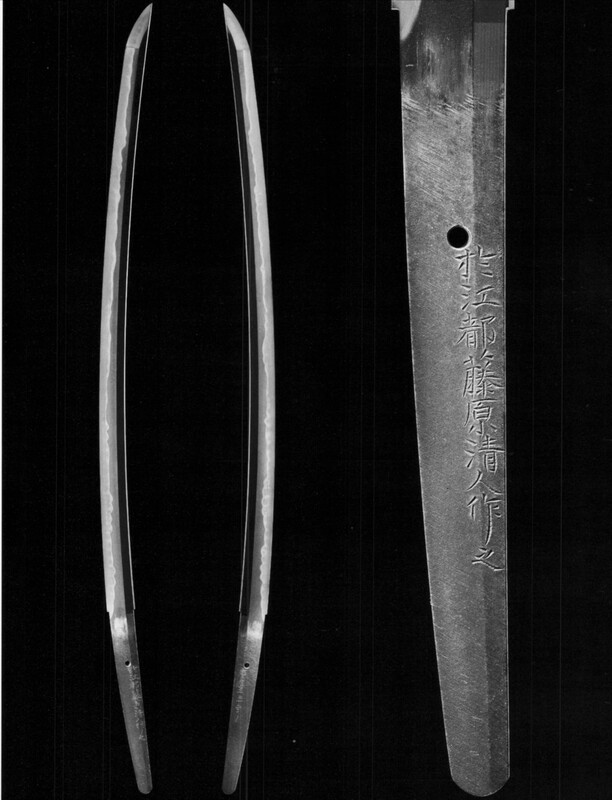

Tametsugu (similarly to Shizu) is not a straightforward smith to put in a category. He moved from Echizen to Mino but maintained his “Northener” Etchu stylistic elements. The NBTHK says of him: “ As for his workmanship, Tametsugu’s jiba is quite nie-laden and we see a standing-out itame with nagare, a blackish steel, a notare-based hamon that is mixed with gunome and that features a very noticeable amount of sunagashi, and a bōshi with much hakikake. Thus, we recognize a mix of northern Hokkoku and Mino elements.” The Zufu entry for the zaimei blade Chris is referring to is attached. The text therein speculates that since it is signed with “Fujiwara”, it is therefore a bit similar in signature to the attached JuBi wakizashi, which is signed with “Noshu Fujiwara” and hence the tachi could possibly have been made after he moved to Mino (but more phrased as a question is how I understand it, rather than a statement). However, as always with Japanese swords, things are not straightforward. The hamon of the tachi does not “look” or feel (at least per the oshigata) stereotypically Mino-ish in nature (with the various symmetrical or pointy gunome features along the entirety of the blade). Per se, that is not an issue as early Mino did not have much symmetry or regularity (cf Naoe Shizu), even though one would expect perhaps more “pointy” elements than in this tachi here. Yet, this tachi seems to have gunome in there. Overall, the zufu setsumei of the Tametsugu tachi highlights the plentiful sunagashi and larger nie in the setsumei section, which I believe is what Chris is interpreting (together with the notare style hamon) as Soshu in style. Lastly, the JuBi setsumei of the attached wakizashi mentions that per Honma sensei the Mino yakiba of Tametsugu is larger / wider while the Echizen (ie more typical Go/Norishige inspired earlier ha style of Tametsugu) is narrower. So, here I believe we have an interesting transitional blade with a more Soshu hamon but a signature that indicates a time period closer to when he moved to Mino.

-

Kiril, thanks. On average, how many signed Kamakura Yamato swords do you come across annually would you say? A rough estimate is fine and the paper could be Hozon and up. You obviously go to various trade shows and buy/sell, so you are in midst of it. Thanks

-

I see. OK, I agree - people should not follow blindly but understand what is being said in context. Nagamitsu, Rai, etc - these are minefields and a lot of study, research and understanding is required.

-

Of course, one cannot take out of context private correspondence between Jean L and Darcy and just extrapolate..... I think the point is that overall proper Yamato (ie Koto) signed blades are rare. It almost does not matter how many there are (eg 100, 110, 120, 150, 200) - the population is very small. Jussi's numbers include Muromachi, which one can argue is a bit misleading. Mumei Yamato are way more numerous.

-

The post and comments that Jean L made referred to signed Yamato blades, and also of certain quality. There are plenty of mumei ones. At Juyo and above level, there are fewer than 170-180 (one needs to double check the entries but my rough count is reasonably accurate, perhaps +/- 5) and that includes some Muromachi stuff. If we are just focusing on Kamakura, then we are in the realm of 110-120. Unfortunately, it is almost impossible to know what the situation is at Hozon/ToHo, unless one has some insider connections into the Honbu and they double check their registers. But chances are that if an Yamato blade is a zaimei and of adequate quality, it will get elevated to Juyo, so the Juyo/TJ Zufu are very good proxy for the overall population.

-

The nakago has been reworked and is thinner than it probably was originally. That could explain some of the large hamachi remaining on the sword. The upper ana could have been the original one, indicating a potentially slight machi okuri. The lower, later ana was probably centred after the nakago had been reshaped.

-

???? https://to-ken.uk/Meetings/2018%20meetings.html

-

The blade subject to the original discussion is an honest, decent and genuine blade in acceptable polish. I am not sure what people are looking for in terms of polishing windows, etc. Everything is visible on the blade and in fact it is is in better shape than most blades found 'in the wild'. It can be appreciated as is. Often one needs to factor in not only the economic cost of a polish but also what can be gained in terms of [incremental] appreciation after the polish, and then all of that should be weighed against the removal of metal and diminishing the blade for posterity. Sometimes, it is just not to be done and the blade is best kept as it.

-

Alex, if I am not mistaken, you are trying to demonstrate that even if the hamon continues (or appears to continue) into the nakago, the sword might still (appear to) be ubu? The third one has a very pronounced change of direction and shape of the gunome, as though the smith was indeed putting a “full stop” or a separator …

-

Kiril, have you witnessed this first-hand? I know N Nakahara has done “educational” seminars in Europe but has he done these in the US? What were they like? Thanks. For information purposes, NN has a blog (in Japanese) in which he regularly postulates his views and some of the entries are quite interesting.

-

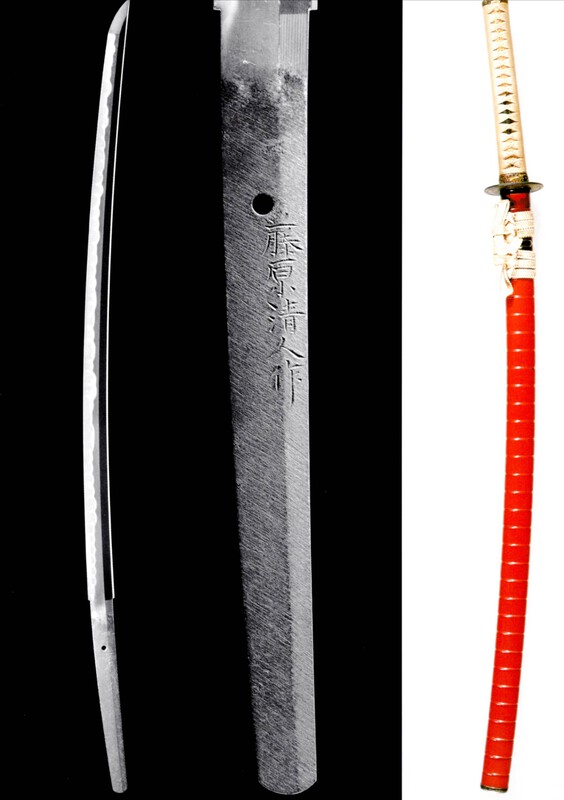

Some Hozon and ToHo papered Kiyondo. He was a skilled smith. Compare the chisel strokes and yasurime.

-

When Tsuruta says that he does “not guarantee the signature”, that is a polite way for him to indicate it is gimei. You need to buy with your eyes wide open.

-

Late Kanemoto is completely plausible and likely on this one. Kanemoto is a Mino smith as is the Seki school.

-

Why Kamakura = best swords ever??

Gakusee replied to Nicolas Maestre's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Nicolas Plenty of ubu Heian and Kamakura blades are available. What the smith intended is very obvious. Also there are plenty of extremely well preserved Kamakura blades. They are just too precious to test against kabuto or steel rods or new swords . I feel we need to shortcut the whole discussion and in the fashion of how some of the scientific papers are structured, quote what has been already discussed and invoke existing research and use it to substantiate elements of the thesis in order to crystallise overall conclusions with that “evidence”: - There was another NMB topic about which the greatest smiths were. In there you might see that the most reputed, highly regarded smiths with the most Kokuho/JuBu/JuBi/TJ blades are actually Kamakura and Heian smiths. In here I of course include most of the Soshu greats, although there is a minor crossover into the very beginning of Nanbokucho. By extrapolation, if the greatest smiths worked mainly / predominantly during the Kamakura period then the Kamakura blades seem to be evaluated as the best. Not equivalent logically but intuitively you understand the Japanese belief. Just on average they seem to be better, not that it always holds. - Why are the aforementioned the greatest/ most highly reputed smiths etc? Well, Japanese emperors, Daimyo and Shogun decided so and we have followed their taste (as it often happens in Japanese culture / history). It is down to a combination of myth + personal taste (eg Gotoba ushering a certain sense of aesthetic or the Ashikaga shogun preferring certain aspect and also thereafter Oda, Toyotomi and Tokugawa favouring Soshu and Bizen etc) + performance in the respective historic period. - Again why / what to look for / understand why the aforementioned Daimyo etc decided as mentioned above: look at Tom Helm’s post explaining the physical features - also consider Chris Hill’s historic diagram (you need to understand normalisations as he has statistically normalised certain things) demonstrating where/ in which period you had the peak of top-rated blades. It clearly shows you the explosion in Kamakura. Honestly, it is not such a difficult question to address. Overall, it is a matter of understanding Japanese aesthetic, history and culture and then interpreting the question through that cultural and social prism. It has little to do with Western perceptions of which steel is best (modern man made vs Japanese - old /new) or even old Japanese (Kamakura) vs newer. A lot of it is simply tradition- and acquired-aesthetic-based. Separately, and subjectively, I agree with some of the posts above that the exciting / differentiated / lively Kamakura hada interspersed with scintillating jinie and konie of Kamakura, or the elegant utsuri of the period are aesthetically superior to the more monotonous or lifeless or homogeneous output of the later periods. Or even when some of the later (eg Shinto or ShinShinto) smiths achieve something outstanding, as an aggregate, across the population of smiths, on average you cannot say that the blades are so pretty or interesting. -

Why Kamakura = best swords ever??

Gakusee replied to Nicolas Maestre's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Hi Chris Time and again we hear the Mongol invasion argument for the transition of Kamakura sugata to Nanbokucho sugata. What people fail to realise or pay attention to is that the Mongol invasions happened in the 1270s-1280s. So some 50 years before we deem the typical “Nanbokucho” sugata. If the Kamakura swords were so ineffective against Mongol armour, the change would have been much faster, almost instantaneous, and not measured in 5 decades. Mongol armour consisted of chainmail covering a thick chemise and on top you could have further leather armour. It is true that swords with a lot of haniku could get stuck in disparate media but this needs more analysis. It is more likely evolution of warfare in Japan itself, the transition of armour (from o-yoroi to haramaki and gusoki) and so on. One last point: numerous of the Nanbokucho swords actually have normal mihaba and chu-kissaki. It is not that all of the Nanabokucho swords are the monsters with 3-3.5 cm mihaba and 6-8cm o-kissaki. So, again, food for thought…. -

Why Kamakura = best swords ever??

Gakusee replied to Nicolas Maestre's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Paz Somehow there was loss of knowledge, skill and material during the transition from late Kamakura into “mature” or late Nanbokucho. Yes, Norishige might have worked during some of Nanbokucho (depending on which texts you believe) but some texts state he was a fellow student alongside Masamune of Shintogo. So these “greats” of late Kamakura such as Shintogo, Masamune, Yukimitsu, Norishige, and also of very late Kamakura / early (up to mid-) Nanbokucho such as Go and Sadamune, Kaneuji, Sa, etc. So, it is perhaps fair to assume that into the first half of Nanbokucho there were still great smiths and great swords. But in the latter half of Nanbokucho and into Muromachi the drop in quality is too big when compared to the peak in Kamakura. For instance, there are amazing Go and Shizu swords (some of them better than some of the Masamune) but when you look at rather late Soshu (Akihiro, Hiromitsu etc), while nice, it is nowhere as good as the Kamakura or early Nanbokucho Soshu. Similarly in Bizen. The greats of Kamakura such as Mitsutada, Moriie, Yoshifusa etc produced swords that were much better than the late Nanbokucho /Oei smiths. I agree that +/-20 years either side of the cut-off it probably does not make much of a difference. It is probably more of a generational difference: the smiths working at the beginning of Nanbokucho having learnt from the Kamakura greats simply could not pass it on to their own students at the end of Nanbokucho. The factors and reasons are not well established for this rapid effervescence. Working in a centralised workshop, be it in Osafune or Kamakura, could have helped catalyse knowledge and skill and then with the dispersal of smiths to different parts of Japan those might have diminished. Of course the increasing intensity of warfare later on exacerbated the trend.