-

Posts

53 -

Joined

-

Days Won

6

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Andrew Ickeringill

-

Any stats on gimei?

Andrew Ickeringill replied to Mikaveli's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

I’ve not studied rocket science, but if one can tell the difference between two atoms by looking at them under a microscope then it’s not **** kantei!!!!!!!!!!! Obviously, if you know what to look for then it makes it doable. -

What are these blemishes on the hiraji?

Andrew Ickeringill replied to Mikaveli's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Tobiyaki. -

Interesting sword... may I ask what kind of kanteisho it has?

-

- 14 replies

-

- 14

-

-

-

- 14 replies

-

- 14

-

-

-

-

Incorrect.

-

Question Re: sword straightening

Andrew Ickeringill replied to Utopianarian's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Straightening the blade is a crucial step of the polishing process, it can also be very risky, so many things can go wrong. Why would anyone advocate a complete amateur to attempt this? No. And to answer the original questions of this thread... - Yes, even very slight bends can be corrected. - By my definition of a slight bend, one or two shouldn’t affect paper levels, I’ve seen them in many a juyo and higher-level blades. -

-

Gassan School

Andrew Ickeringill replied to David Flynn's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

I'm not sure of the exact technique used Bryce, but I've had a conversation about it with a smith who uses the same technique on his own "home-made" habaki. Because he's not trained in habaki making, he doesn't have the skills to foil, and said the wash technique was the only way he could apply gold, which was very dangerous... but in typical Japanese fashion, he didn't seem to care much, his health is secondary to his work. I thought it was common knowledge that Sadakatsu made these habaki. I've had discussions on this topic with former mukansa shiroganeshi Miyajima-sensei, as well as students of the Gassan line. I would consider that a definitive source, but others may only consider that hearsay, all depends on perspective. -

Gassan School

Andrew Ickeringill replied to David Flynn's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

I was referring to gold foil habaki vs solid silver/copper habaki, didn't think I'd have to clarify that, of course a solid gold habaki would be more expensive than a gold foil habaki. As for which is more desirable, I suppose that could be subjective to some. -

Gassan School

Andrew Ickeringill replied to David Flynn's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

And so these would've been made by someone else I believe. Foiled habaki are much more difficult to make than solid, and hence more desirable/expensive than solid. So I think it's safe to assume that if Sadakatsu was proficient at gold foiling, he wouldn't have been risking his life with the gold wash process. -

Gassan School

Andrew Ickeringill replied to David Flynn's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

From what I understand, Sadakatsu made his own habaki, which is why you see so many of his blades with this style of habaki. They’re solid silver, I don't think he did foiling, the gold habaki are solid silver with a gold wash (you'll see on most of them that the wash is fading towards the bottom, where the habaki makes the strongest contact with the koi-guchi) I believe it’s applied in liquid form and the application can be very hazardous to your health. So, if you have a Sadakatsu with this style of habaki and you’re having the blade polished, I recommend trying to re-use the habaki rather than having a new one made, it’s rare for a smith to make his own habaki, and they’re definitely worth keeping together. -

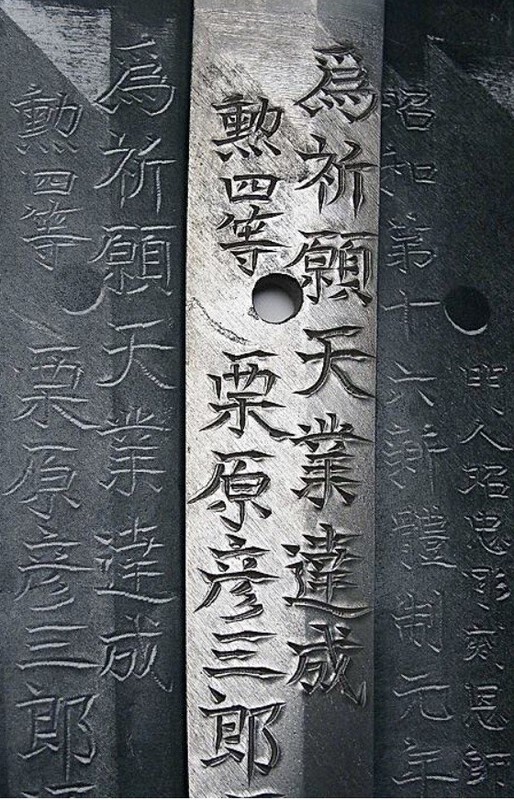

Yes, there are many differences in the horimono both in terms of style and quality which raise suspicion… actually, a huge gap in quality! As well as many differences in the deki of the sword, which wouldn’t be so if it were a shadow sword made at the same time as the original by Akihide. But to me, the big giveaway is with the nakago. The original has some minor openings in the nakago just to the left of the mekugi-ana which appear as a sort of scarring, the faker has attempted to reproduce this scarred effect in their sword, but the angles are incorrect, it goes off in a different direction. Which logically points to the 2nd sword being an attempt at a direct fake, rather than a shadow sword by Akihide. (Original to the left, fake in the middle) Once this is clear, and you start to really analyse the tagane and yasurime, the differences start to jump out at you. No sword should be assumed shoshin simply because of the supposed period or maker, wherever there’s money to be made, there are fakes to be made.

-

I believe these two swords have been discussed before in one of the FB groups, the topic was raised by Chris Bowen. They’re actually both dated 1941, in fact the inscriptions are exactly the same on both swords, though clearly made by different hands. The one with the hozon paper is of course legitimate and quite a well-known sword by Akihide, the other is an elaborate fake, so maybe not congratulations, but commiserations to the buyer

-

To clarify further tsukurigane 作り鉄 (literal translation = made steel) is a forging process that involves mixing steels of varying carbon content in order to produce a chikei-like effect in the jigane. If you’re after a more definitive translation, I don’t really have one, but it seems the term is used for any kind of jigane that contains chikei that weren’t formed “naturally” in the forging process, such as ayasugi-hada, uzumaki-hada, the imozuru found in satsumato or the matsukawa-hada of Hankei. So, perhaps the closest translation is ‘unnatural steel’? But to me, that’s not a very flattering definition, especially when looking at the incredibly beautiful results of this technique when performed by a master. I’ve also heard the term mazegane 混ぜ鉄 (literal translation = mixed steel) used to describe the same or similar process. I’ve heard some craftsmen use the terms tsukurigane and mazegane interchangeably, while I’ve heard other craftsmen separate these two terms as slightly different, based on the materials used I believe. I think it depends who you ask and their school of swordmaking, but I’ve not seen these terms explained before in text, only heard them in conversation, so it’s difficult to nail down exact definitions/translations. You could call tsukurigane and mazegane both 'mixed steel' and you'd be correct, yet to some craftsmen there are differences. Hope that helps somewhat.

- 104 replies

-

- 12

-

-

I wouldn't say a position of knowledge Brian, but maybe a little further insight, but thanks for allowing me to post because this was an interesting topic, too bad it branched off into the absurd… let’s see if we can bring it back on course a little. I’ve been lucky enough to polish a couple Naotane in my time, and I feel I have some understanding of his work. I’ve been even luckier to have had many discussions with people who know far more than I do about forging techniques, and I believe one particular technique I’ve learnt about has some relation to this discussion. Naotane was a master of the shinshinto period who was able to produce incredible work in many different styles. There were of course several smiths of this period who skilfully produced swords in different styles of the gokaden… but Naotane was able to produce several different sub-styles within each of the gokaden in which he worked, but rather than just changing the type of hamon, he used completely different forging techniques, which is where his genius lies for me. For example, just in his Bizen-den alone I’ve seen several different approaches used: - He made Kagemitsu and Oei-Bizen utsushi using typical forging techniques and tsuchioke to create a more controlled yakiba and utsuri on a ko-itame hada. - He occasionally used a mixed hada in his Kagemitsu utsushi, with a flowing chikei mixed in with ko-itame hada. - Sometimes he made a pronounced uzumaki-hada in his Bizen-den, which I’ve heard as being a kantei point of his, though I’ve not often seen it. - And rarely, he made Bizen utsushi using hadaka-yaki to produce more wild yakiba and stronger utsuri formations. Naotane’s Uzumaki-hada in Bizen-den. I’ve also seen him create Yamato-den with thick bands of masame-hada, and Soshu-den with swirls and burls of chikei similar to Matsukawa-hada… the point is, he was probably the most versatile smith of the shinshinto period, especially when it came to creating different jigane. During a time when many smiths produced very tight hada, sometimes even muji-like hada, Naotane was forging masterful steel with flowing chikei and utsuri. One of the techniques he mastered in order to achieve this variety of steel was called tsukurigane, it’s a term I came across early in my polishing apprenticeship, and I’ve not seen it mentioned in any texts that I can recall. It was explained to me as a way of forging steel that reliably produces a clear and controlled ‘chikei-like effect’ which several modern-day makers were using in their Soshu-den utsushi. But, it’s not the way chikei was typically created in koto work, except for a few schools such as the Norishige school, who I believe used some form of tsukurigane, but that’s a completely different rabbit-hole and a completely different level of genius! Tsukurigane (‘tsukuri’ generally translates as ‘making’ or ‘to make’ or relates to a particular technique of manufacture such as ‘shinogi-zukuri’, but in this case I believe ‘tsukuri’ infers a meaning of the steel being controlled or contrived). It’s a type of kawagane which is made by forging together two or more different billets of steel, often forging them together using a relatively low number of folds. The different billets used in the process can each be folded in the same pattern (e.g. ko-tame) and can be of the same number of folds, so when they’re combined, there’s no discernible difference between them in terms of the pattern or the fineness/tightness of the grain. But, these different billets usually have vastly varying carbon content, which means once polished they’ll produce different colours and textures, and different amounts of ji-nie, which is what creates the chikei effect running through the jigane. The less you fold these billets together to combine them, the larger the chikei pattern it’ll create, and the larger the difference in carbon content, the more contrast there’ll be in the chikei. Apparently, combining them using limited folds, but without producing kitae-ware is extremely difficult, but when done masterfully as Naotane was able to achieve, it can create a very beautiful chikei effect flowing through the jigane. Naotane’s tsukurigane producing a masame/mokume mixed effect. I once opened a window on a Naotane that was in Bizen-den and was a great example of tsukurigane. Something I found fascinating was, once I’d brought out the jigane, on some angles it would appear as a very tight ko-itame with only a hint of chikei in the background, while on other angles swirling chikei would jump to the surface and completely change the overall impression of the steel. It was a brilliant effect that gave the steel a lot of depth, and it made me think about how different a sword can look on different angles or under different lights. Of course, the polish makes a huge difference as well, the previous polish was acid-etched and gave the steel a damascus-like effect. These two pics are of the Naotane I just described, as you can see one shows a tight ko-itame, and the other shows a flowing chikei effect running through it. But the pics are of the exact same section of steel, at the same point of the polishing process, under the same light, in the same room… just on different angles. I believe all of the above relates to the juyo katana which started this discussion… I definitely see tsukurigane in this sword, which is creating a lot of chikei, but I’m not sure I specifically see mokume-hada or uzumaki-hada. There are definitely some patterns which hint at something reminiscent of mokume, but I don’t think they’re actually forming a proper burl pattern, it seems that they’re a sort of wavy/churning chikei effect, so personally I don’t think I’d call it mokume. Either way, the chikei created by this style of forging can exist within a tight ko-itame, so even if there were mokume or uzumaki patterns in the chikei, I could understand the NBTHK defining it as ko-itame. It’s not easy sometimes to define a hada, for me, the strength and clarity of which a pattern appears, and how often it occurs over the whole sword are big factors in defining it, and I imagine those are also factors in determining whether or not it’s mentioned in an NBTHK setsumei. But I’m no expert, and I haven’t seen this sword in hand, which is really important as pictures can be misleading, as I mentioned above, a slight change in light or angle can completely change the appearance of certain types of jigane. The NBTHK on the other hand are experts, and have seen the sword in hand, in fact they’ve studied it at length as they’ve passed it as juyo. So, I think the point that Jacques is trying to make is valid, they’ve not mentioned mokume or uzumaki in their setsumei, so one can fairly surmise that there isn’t any in the forging. I will say though, there are perhaps better ways of trying to get your point across, and the discussion would’ve been better off if its contributors were maybe more considerate. Perhaps there are language barriers, or things are being misconstrued as they often can be over emails and forum posts, either way an interesting discussion that merits more thought. That’s just my 2 cents.

- 104 replies

-

- 21

-

-

-

-

Yes, quite often, to varying degrees, most of the time the difference is negligible and it would go unnoticed by most people.

-

The first time I ever performed hi-togi during my apprenticeship, I asked my sensei the same question. He explained that sometimes the asymmetry in the hi-saki is done deliberately, as ending the hi on both sides in the exact same spot can create a weak point in the kissaki, which puts that area at higher risk of taking fatal damage during use. However, he added that not all hi are carved with this in mind, and some asymmetry you see here could’ve been caused by polishing, but polishing alone doesn’t account for all cases. The same explanation was given to me by a mukansa-ranked tosho, who occasionally used this technique, depending on the dimensions of the blade.

- 11 replies

-

- 12

-

-

-

A word about amateur polishing

Andrew Ickeringill replied to Brian's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

The most basic requirement is to put in the necessary effort yourself. -

Hi James, yes there are many examples of hadaka-yaki being executed to an extreme degree of skill in the Ichimonji school. However, the craftsmen I mentioned were referring to more recent attempts at hadaka-yaki (shinshinto – gendaito). I thought this was inferred by your original question “modern smiths have yet to rediscover "true" utsuri” but reading my post back I don’t think I was clear in this point. These two different heat treatment methods can produce very different results with utsuri, and while I don’t necessarily agree with the view that one method is better than the other, I do understand that some craftsmen may prefer one method over the other. From my own perspective, I’d say that just like every other feature of Nihonto, not all utsuri is created equal. Being able to judge the quality of the activities in the steel is a large part of judging the quality of a Japanese sword. To me this has less to do with the methods used to create the sword, and more to do with the degree of skill and experience that went into these methods. But I’ll add that these views were shared with me by senior craftsmen who I respect, some of whom have dedicated their lives to reproducing Bizen style swords, so I wouldn’t dare assume I know more than them on the subject. What is for sure in this field of study is… the more we learn, the more we realise we have more to learn!

-

What is "true" utsuri? What isn't? The question in this thread could be interpreted in different ways, I believe James is probably referring to hadaka-yaki, but I'll touch on a few different things that come to mind. 1) Yes, there are swords on the market (particularly coming from Japanese auction sites) that have fake utsuri. It’s a chemical technique applied to the blade in the polishing process, which is designed to resemble utsuri on certain angles. However, the examples I’ve seen have been rather crude and obvious, and can easily be detected through pictures. I’d also like to make clear that this technique is not being applied by traditionally trained togishi, I’ve only ever seen it on blades that were defiled by hobby-polishers/self-taught hacks. If you want more info on how to spot fake utsuri, please read the following link: https://www.facebook.com/toukentogishi/posts/2401556073244615 If you don’t do facebook, it was also posted on NMB: https://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/28800-warning-about-fake-utsuri/?tab=comments#comment-291807 2) There is another type of fake utsuri that appears in Nihonto, though you wouldn’t really refer to it as fake, as it’s very much a naturally occurring effect, not an artificial effect applied in the polish. It’s called tsukare-utsuri. Tsukare-utsuri literally translates as ‘tired utsuri’ and it occurs when shingane (core steel) is exposed. More often than not it can be found in lower-quality work of the Muromachi period (known as kazu-uchimono) which is known to have especially thin kawagane (skin steel). Tsukare-utsuri forms a loose/hazy utsuri-like effect in the steel that… - sometimes appears only around the border of where kawagane becomes shingane. - sometimes it completely fills that area of shingane. - or sometimes appears in patches within that area of shingane. In any case, it doesn’t look very appealing, it's definitely not a desirable trait in a sword, and you should be able to recognise it as something other than "true" utsuri. 3) Then there is the question around hadaka-yaki (heat treatment without clay) which is most likely what the question in this thread is about. During my training I was lucky enough to have quite a few conversations regarding utsuri with other craftsmen, and I get the impression that some of them believe that the utsuri produced when hadaka-yaki is performed on a blade is not really considered “true” utsuri. I recall one such conversation with several togishi at NBTHK kantei-kai. There was an exceptional Naotane which had very strong utsuri, and I was keen to understand why it was so much stronger than utsuri I’d seen in his work before. It was explained to me that “yes, this utsuri appears strong, but… this is only hadaka-yaki, and Naotane rarely used this technique”… implying that hadaka-yaki was a lesser way of achieving utsuri. I’ve heard similar remarks from tosho who work at producing utsuri when using tsuchi-oke (applying clay for heat treatment). Apparently, producing a clearly visible utsuri on a consistent basis is more easily achieved when using hadaka-yaki, but that type of utsuri can often appear wild and unrefined. So it's viewed by some as a greater achievement to produce prominent utsuri using tsuchi-oke. It’s a fascinating topic that deserves further study and debate, but I won’t wade into those depths today. I will say however that from recent efforts I've seen, it seems modern tosho are continuing to advance their abilities and re-discover the "secrets" of utsuri using both methods. Lastly, I’ll add a little article I posted a while ago, it’s a beginner’s guide to utsuri that should give you a little more info and some instruction on how to view it properly: https://www.facebook.com/toukentogishi/posts/1109394242460811?__cft__[0]=AZX5euUw0LcK-KtWaluQagI_Mp3mJ_MjHaxXY3D8nwx2FUANlNbxuChojfhd7LXkGKTJPIQa53xCp92Q9iuUGaQhj2gI1DAz03C4pGBNqEbXGglfyD-a1360xzhwIr8ZhQmn_ljmPPS351Mu31OHJynoJNKq8gQFGloA9qcDyRHbbp6-yAOqH73jfStPElKolfI&__tn__=%2CO%2CP-R

-

Can modern smiths create a vibrant utsuri like in ko-Bizen blades?

Andrew Ickeringill replied to piryohae3's topic in Nihonto

But I should add that none of these smiths can produce utsuri like that of the Ko-Bizen smiths!! Or any school from the Heian - Early Muromachi period for that matter!! -

Can modern smiths create a vibrant utsuri like in ko-Bizen blades?

Andrew Ickeringill replied to piryohae3's topic in Nihonto

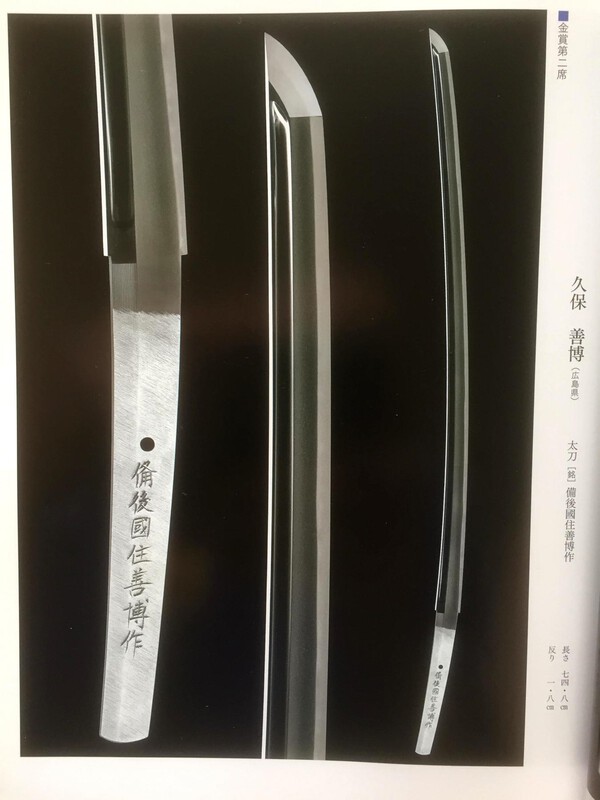

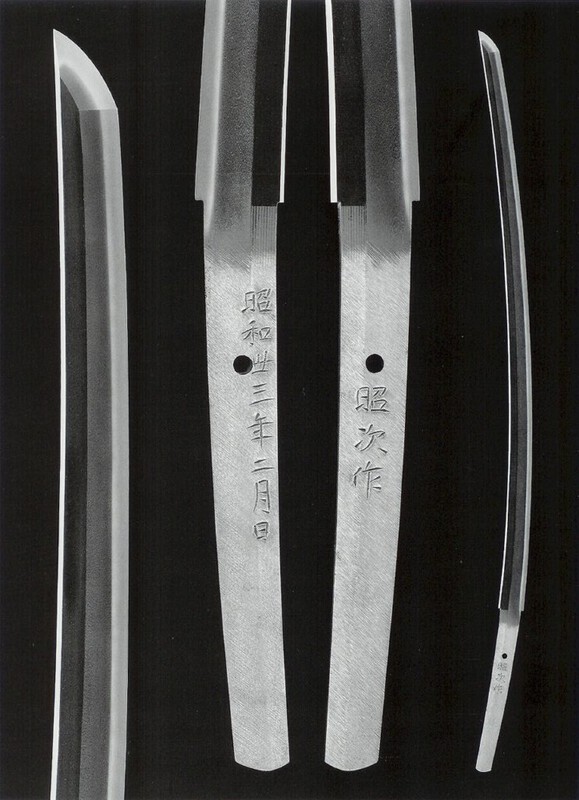

Shinto – Ishido school – particularly Korekazu and Tatara Nagayuki Shinshinto – Naotane, Soukan Shinsakuto – Kawachi Kunihira, Yoshihara school - particularly Kubo Yoshihiro Basically, there were relatively few smiths in these periods that were able to produce strong utsuri consistently. You can find utsuri occasionally in the works of other smiths not mentioned above, but being able to produce deliberate utsuri of consistent quality is a whole different matter! Another thing to consider, many tosho of the Shinto period were striving to create new styles (Shinto Tokuden) and weren't so focused on reproducing the work of earlier schools. For example, Tsuda Echizen Sukehiro was a master of the Shinto period, and was fully capable of producing utsuri, but he's not known for it, it's not a kantei point, because you won't find it in his blades with toranba which is what he's most known for. But he also made Yamashiro-den utsushi in suguha, which often have utsuri, sometimes of phenomenal quality. For modern tosho I make special mention of Kawachi Kunihira and Kubo Yoshihiro... A few years back, I was able to view the sword that won Kawachi Kunihira the Masamune-sho, for me it was probably the best Bizen utsushi I’ve seen of the last 100 years, the utsuri was outstanding! As for Kubo Yoshihiro, his Aoe school utsushi have very nice consistent utsuri, even on his suguha tachi, which is a real achievement as this technique doesn’t involve hadaka-yaki. Here are a couple pics (sorry for poor quality, taken on my phone) of Kubo Yoshihiro’s work and a link to a doco featuring him and his deshi: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0glduW4-EPY&fbclid=IwAR39oFJLHEcqzMzmNrHz5OTuQFZsAV70gUhsXoPidDQeWnvbPqOZrRret4s -

As you've already realised, Bizen-den and Soshu-den are by far the most popular styles being made by modern tosho. Other popular styles are Kiyomaro and Sukehiro utsushi. Those working in Yamashiro-den, Yamato-den or Mino-den are few and far between. Yamashiro-den: Amata Akitsugu was definitely the best I’ve seen to have worked in Yamashiro-den in modern times (attached are a couple examples of his work in this style), though he was also excellent in Bizen-den and Soshu-den as well. Unfortunately he passed away a few years back and I don’t think his students work in Yamashiro-den. I can’t think of any other smiths off the top of my head who are currently working in Yamashiro-den, but if you go back to Gendaito you have the Yasukuni group of smiths who focused mainly on reproducing the work of the Kamakura Rai school. Yamato-den: The modern Gassan line often work in Yamato-den, occasionally forging blades in pure masame-hada which are aimed at the Yamato Hosho school. And of course, their ayasugi-hada is a technique that was also produced by the original Gassan school of the koto period, which was a Yamato-den school. Mino-den: You’ll find that the modern smiths who are working in Mino-den are usually reproducing the style of Shizu Kaneuji. Though a lot of these utsushi are perhaps closer to Soshu-den than Mino-den, Kaneuji being a smith who started the Mino tradition but whose work was strongly influenced by Soshu-den. You won’t find a whole lot of sanbonsugi these days! ???? The Kanefusa line are still producing swords in Gifu I believe, the current head of the school is the 24th or 25th gen and his Kaneuji utsushi are excellent.

- 9 replies

-

- 10

-