-

Posts

4,209 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

93

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by SteveM

-

I should say one of the things I read online was that this technique was a way of using acid to highlight any forging lines in the base metal, and then incorporating those forging lines into the design that was to be carved on the base metal. (like using the lines to represent water or clouds). Another site I saw said that kusarakashi was a way of adding texture to a plain (flat) base. Hence, it seems to be an elastic phrase - but one which involves applying an acid treatment or a rusting agent to the metal to elicit some textural effect.

-

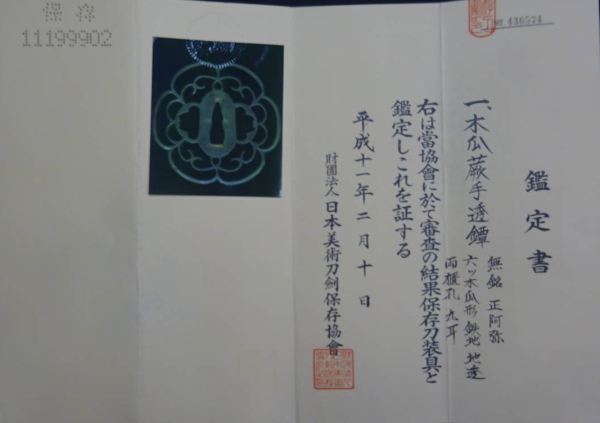

I see the NBTHK uses two different pronunciations Yakite kusarashi, and Yakite kusarakashi The meaning is the same (both are the causative form of the verb 腐る - to decay, to rot) Haynes defines it as a surface design or finish that is made by acid treatment. So, basically as Jean mentions above. My dictionary of sword-related terms defines it as applying an insulating substance to the design element, and then applying acid to the rest of the tsuba, so that the design element rises a bit above the surface. Digging around a bit more online, it seems to be a rather elastic term for various acid treatments. Attaching a picture of a part of another NBTHK appraisal to show the alternate reading. I wish they would standardize.

-

Some slight corrections. (Using the old kanji so that they match with what's on the seal. 檢査證票 (meaning is as above, just one kanji left out) 関刄物工業組合 (meaning is as above, just 刀 should be 刄) 岐阜縣関町 (Seki town)

-

Nakago Translation on Interesting Blade

SteveM replied to Northeastern Port's topic in Translation Assistance

Dedication is: 為渡邊社長 For President (CEO) Watanabe -

尾崎平左衛門 Ozaki Heizaemon Or 尾崎半左衛門 Ozaki Hanzaemon Nothing pops up in a quick search except for Ozaki Gengoemon

-

The kuzushi version of 重 is very different from the one on this tag, so it can't be 重.

-

Yes, that's a safe bet. What I was hinting at with my post is that if you contact that city, there is a chance that you might get a lead on how to contact someone in the Dōtomi family. It's a city of fewer than 3000 people. Everyone in that town knows someone named Dōtomi. If you can get in contact with the family, they most likely have memories and records of a grandfather or grand-uncle who was in Manchuria, working for the railway. This assumes that you want to repatriate the sword. You can also try to repatriate the sword through services of a group called the Obon Society, or through your nearest Japanese Embassy. The thing about the Dōtomi name is that it is so rare, and so specific to that one location, it shouldn't be too difficult to try to make some enquiries on your own. But I'm saying this as someone who speaks and writes Japanese, so mine is not an unbiased opinion. If the name were the equivalent of Smith or Jones, it would be quite challenging to find any descendants, but Dōtomi is unique, so I feel it wouldn't be so difficult. If you don't wish to repatriate the sword, and are just looking for information on the person, it becomes a bit more difficult.

-

That there are so many people wanting to authenticate their swords and tosogu is, in a way, a validation of the popularity of the current certification system. But it also exposes the limitations of the system. Its become a victim of its own popularity. There is a shortage of people who can act as competent judges, and the blame for this falls squarely on the NBTHK. One of their raisons d'etre is to educate the public about swords and fittings, and to this end they have study groups, seminars, publications, and a great deal of space in their sword museum is dedicated to lecture rooms (the three-story Sword Museum in Ryogoku, has two floors of study rooms and offices, and only one floor of exhibition space). They also know very well the looming problems of an ageing panel of judges, and the dwindling number of experts. So the failure of the NBTHK to educate and train a new and expanded panel of judges is a failure of the current management. Who is the next Tanobe, the next Honma Junji, the next Sato Kanzan? Why hasn't the NBTHK fostered the development of the necessary expertise? In a related note, the museum isn't a tremendous improvement on its previous incarnation (when it was located in Yoyogi). As I said, the swords are on one floor of the three-floor structure. The information cards are in Japanese, except for the the swordsmith name and the dates, which are listed in English as well, with multiple spelling errors. It feels very amateurish. There is a QR code you can scan to get English explanations, but the English explanations use machine translations, and, again, it leaves one feeling that not a lot of effort has been made to accommodate foreign visitors. I should also say that maybe 1/4th of the visitors were non-Japanese on the day I went. Anyway, the appraisal system is, I think, necessary and beneficial to the collecting community, but some things at the NBTHK need to change to ensure it stays relevant to the times and the current population of collectors.

- 22 replies

-

- 11

-

-

The name Dōtomi is one of the rarest in Japan. On the site I use for researching Japanese names, it says there are only 10 people in Japan with this surname, and they all live in Nagasaki prefecture, Ikishi city (長崎県壱岐市). No doubt they are all related. Source: https://myoji-yurai.net/searchResult.htm?myojiKanji=堂富

-

For the sword enthusiasts in Southern California, there will be a meeting of the Nanka Tokenkai ("Southern California Sword Club") on Friday, April 12th, at the Gardena Valley Japanese Cultural Institute in Gardena from 7:00-9:00pm. For information check out the club's Facebook page. https://www.facebook...174273/?ref=newsfeed Gardena Valley JCI, 1964 W. 162nd Street, Gardena, CA 90247

-

From left to right 京都住国吉 Kyōto-jū Kuniyoshi (presumably the name of the smith) 生中心 Ubu nakago (means the tang is in its original shape) 長サ貮尺貮寸参分有之 Length of cutting edge: 2 shaku, 2 sun, 3 bu (67.57cm) 井上正實 Inoue Masazane (a name)

-

My guess is shibuichi. The box says 東京銀座 Tokyo Ginza 株式会社 Kabushiki Kaisha 山崎商店 Yamasaki Shoten (was a dealer in precious metals and commemorative gifts in Tokyo) 謹製 Made respectfully/with care

-

Wakizashi genuine signature/mei?

SteveM replied to VRGC's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Hello Victor, Reiterating Franco's comments. It's often difficult to just look at a mei and validate the authenticity. This is especially difficult with lesser-known smiths. And still more difficult if, as in this case, some part of the mei is illegible. If the mei is supposed to be Kanetsune, we can say that the final kanji doesn't really look like 常 (tsune). it looks more like 定 (sada). But its too eroded to say with any confidence. And, if there is no known smith who signed as "Kanda-jū Kanesada", then we're stuck with a Kanetsune mei that doesn't look very convincing. But as Franco says, the normal thing to do is to look at the sword and make a judgment as to whether or not the sword looks like a sword from Kanetsune. There is too much uncertainty to say whether the sword is gimei or not (but it definitely looks problematic to me). -

金刀比羅 Kotohira shrine in Kagawa Prefecture. The stamp is maybe a quality inspection stamp. I should also say that obviously the "art name" looks like るま堂 (Rumadō), but I'm not full of confidence regarding the names.

-

middle of top picture 参拝記念 visit to shrine commemoration bottom picture is the gō and name of the carver. Can't quite read the gō 翁??堂 成子彫 (茂子彫?)Carved by Naruko? Shigeko?

-

The signature on your sword is 廣近, not 弘近, so the smith on your sword can't be the one below. Plus, the patina on your tang looks very recent. And, as far as I know, no swordsmiths signed with a date using just the zodiac animal. It is too vague a date to be useful. It is like saying, "I made this in a year that ends in "4"". Its just not a useful way of dating things. It needs to have the era name and/or the elemental branch that defines the date.

-

Hard to tell. I was thinking 子 or something along those lines, but if these numbers are generally preceded by katakana characters, then ネ is a possibility.

-

Year of the dragon comes every 12 years. It just so happens that 2024 is the year of the dragon. So the previous one would have been 2012, then before that would have been 2000, etc.

-

奈良利壽 Nara Toshinaga Not an authentic signature.

-

Not a poem. It should be a signature. 友雄鏨 以彫?鍛 I think its saying made and carved by Tomo-o. I can look for other references if you let me know what the item is.

-

昭和十五年 (Shōwa 15. The last character is "year"). The other side says 山本正雄 (Yamamoto Masao). Not a swordsmith name. Not typical writing for the name or the year, and the patina looks funny. I have some doubts about this being a Japanese sword.

-

On your sword you have 越前守源 Echizen-no-kami Minamoto 越前守源 Echizen-no-kami Minamoto Minamoto is a clan name. It is common to put a clan name on swords, and Minamoto is the most common clan name. It wouldn't be too hard to give a final verdict, I think, but often it is hard to do so just by looking at photographs. Actually the sword tends to be more important than the inscription. What I mean is, the appraisers will look at the sword, the shape, the tip, the steel, the grain, any crystal structures in the steel, etc... and base their determination largely on those things, rather than on the signature. Well, of course they look at both, but if the sword is a perfect match for what a Nobuyoshi sword should look like, they will accept some slight variations in the signature. On the other hand, if the signature is a perfect match, but the sword shows a lot of deviations from a typical Nobuyoshi sword, they may deem the sword to be a fake. Swords were shortened for a variety of reasons. It is very, very common in the sword world to find a shortened sword. Maybe the sword was damaged and was shortened to remove the damaged bit. Maybe the original size was too long for the person who acquired it, and so they wanted it shortened for ease of use. Or maybe the sword was acquired by a non-samurai, who wasn't allowed to have a long sword, so it was shortened to comply with the rules for swords for commoners.

-

Hello Hylke, The actual name, Nobuyoshi, is cut-off. We can guess that the name Nobuyoshi would have been on the part of the tang that was cut off, but it doesn't actually say Nobuyoshi (nor does the registration card). If you have photos of the NBTHK certificates, it may indicate who they believe the maker is. Echizen is the name of a province. It corresponds to current-day Fukui and Ishikawa prefectures. The actual title is "Kami" (守), and it was granted by the government. Its more or less a courtesy title, meaning Lord, or sometimes translated as Governor (although the title doesn't come with any special authority). So its kind of of like "Lord of Echizen". The smith would apply to the government to receive this title. The emperor would have little to do with it. And the smith might not even live or work in Echizen. Its just a title granted to show that the smith is a good smith. Well, the government makes some money from receiving the request and granting the title, so it is a bit "transactional" as they say. The chrysanthemum symbol may require the emperor's approval - I'll have to dig into the books. My gut feeling it that all of these privileges were controlled by the government (not the royal family), and the emperor was marginally involved, if at all.

-

↑ That's the one I saw. And here's a screen grab of the papered one (Shōami) from Yahoo Japan. I like the design, and I think I like Robert's the best out of these. Looks just a bit more delicate, but that may be a trick of lighting. Anyway, a nice-looking tsuba.

-

I would have said Owari or Akasaka, but as I was looking around for references I saw an identical one on Yahoo, papered to Shōami. (And, I just found a similar one advertised in Europe, labeled - but not papered to - Owari).