-

Posts

154 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

1

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Tim Evans

-

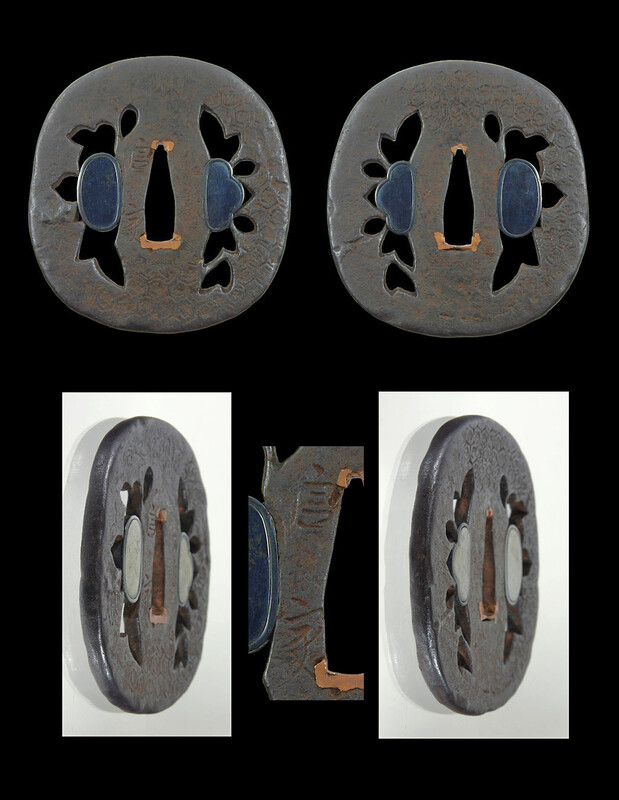

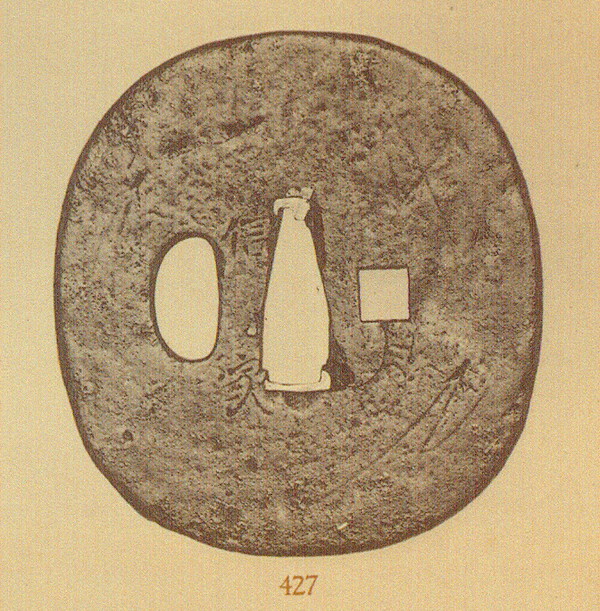

Thanks for the post Steve, that is a good example. Here is another that I published in the 2017 KTK catalog that I think demonstrates intentional sabi. The description in part... "The nunome decoration is a thickly applied, very high karat gold and is suggestive of the gold lacquer repairs seen on cracked tea bowls. The purpose of the gold nunome is to invoke a sense of sabi. The fan papers sukashi (gigami) design was used as a mon by several Daimyo, but also recalls the artistic pastime of painting the fan paper before mounting on the fan ribs". Although the gold nunome looks random and sparse, it is all there. These are not the remnants of a flaked off decoration.

-

"Impermanence or permanence, depending on your point of view?" That is very Buddhist. Very nice tsuba.

-

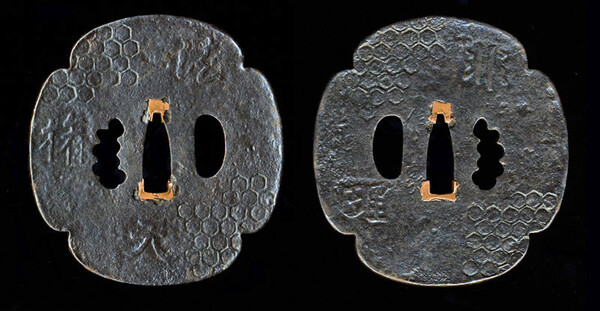

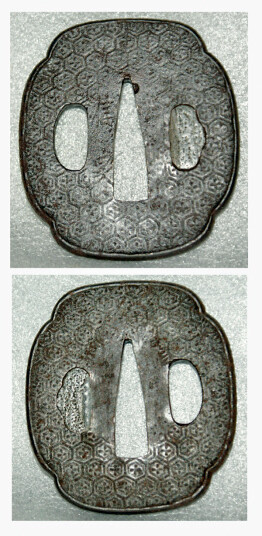

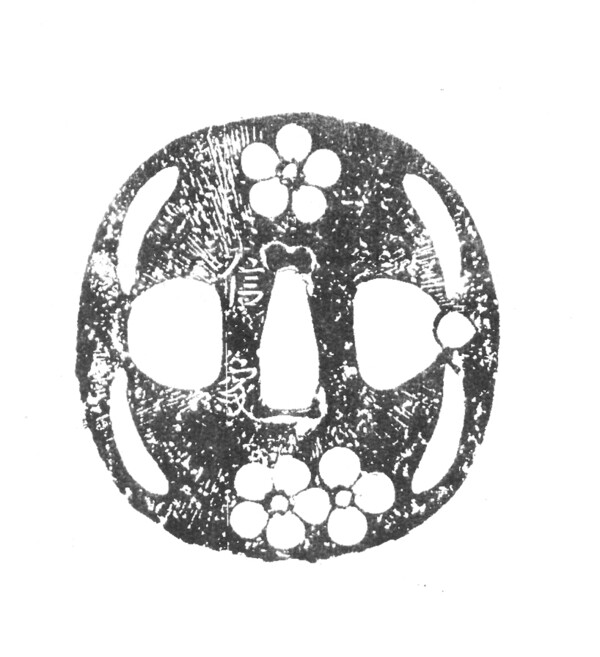

The design is a shippo pattern, which refers to "seven precious things". It was used as a kamon by several families. Based on the one image, I agree that that the smith intentionally made the tsuba in a rustic/sabi expression, which is considered to be informal. The presentation of the design, however is formal, so the overall synthesis is semi-formal. A good book on kamon is useful in deciphering these designs. One I like is Mon - The Japanese Family Crest by Kei Kaneda Chapplear.

-

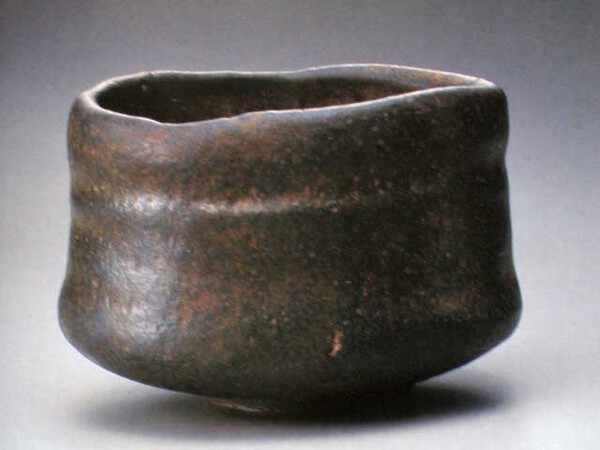

Some additional thoughts on the topic of sabi Many of the more recent attempts to explain sabi go to the “mellowed by use” idea that implies that these objects have wear and deterioration due to age and use, and since many of the objects that have been identified as having this characteristic are now old, there is an assumption that sabi equals antiqueness. What must be understood here is that there are intentional sabi objects were made to look the way that they look from the start, so their original appearance was not due to the accidents of time. D.T. Suzuki points this out in Zen and Japanese Culture: “When this beauty of imperfection is accompanied by antiquity or primitive uncouthness, we have a glimpse of Sabi, so prized by Japanese connoisseurs. Antiquity and primitiveness may not be an actuality. If an object of art suggests even superficially the feeling of a historical period, there is Sabi in it.” What can be confusing is that there are old deteriorated objects that are also referred to as sabi, but the original appearance and intention of the maker was very different. For example, kotosho and kokatchushi tsuba. Unlike later iron tsuba, the preferred appearance in the collector community of these two classes of tsuba is to leave them crusty looking in order evoke the sense that they are 600+ years old. We do not know what the original appearance of these tsuba looked like, my impression is their surfaces were originally much smoother and cleaner than how they typically look now. They acquired their sabi by accident rather than by design. There is also confusion about two Japanese words that sound like sabi. There is one that refers to oxidation, such as when the term kin-sabi (gold rust) is used. The other one refers to specific appearance characteristics of objects that will be explained further on. Because of its relationship to objects, we are on firmer ground in discussing sabi in regard to sword fittings than wabi. Here is a quote from Sadler’s Cha-No-Yu that may be a good starting point (In reference to Honami Koetsu): “As a lacquer artist he mixed brilliant gold with dull silver and lead on his writing cases and incense boxes, bringing a feeling of the ’Sabi’ of the Higashiyama age into the gorgeous fashions of Momoyama.” So, “sabi” is a form of elegance with a particular antique “look” that was valued by the Japanese upper classes in the 15th and early 16th centuries. In Cha-no-Yu, it was introduced as a part of the earlier shoin-cha and re-emerged with daimyo-cha (which evolved shortly after wabi-cha). As Plutschow states in his book, Rediscovering Rikyu: “Under (the Daimyo tea masters) Enshu and Sekishu, Confucianism gradually replaced Buddhism as tea’s underlying philosophy. Confucianism and Neo-Confucianism were about to become the official Tokugawa ideology and even Rikyu’s direct descendants, the so-called Senke schools, could not avoid it. Thus Rikyu’s tea changed from wabi to kirei-sabi.” Impermanence is a cornerstone of Buddhist teaching and practice; a key fact of reality that must be dealt with. I believe the intent of objects made with sabi characteristics is to acknowledge, accept and celebrate impermanence. This was why the characteristic of sabi as expressed in objects was valued, particularly by Buddhists and Warriors. One way for sabi objects express impermanence is to show process, in that we can see how they were made, and/or in that they (deliberately) look a little unfinished. For example, the yakite effects on Yamakichibei tsuba, which are semi-accidental and provide interest and movement in a natural way. There is also the process of time. Sabi objects were deliberately made to look old and worn. This is not the same as naturally deteriorated. Carving, inlay and onlay were rubbed down make them look gracefully aged and used (what is contemporarily called in the antique business, "distressing"). Also, repairs, such as sekigane were created for effect. This is sometimes difficult to judge if the effects were done well. On thing sabi is not, is crudeness, as in poor workmanship or materials. Made-as sabi objects were very sophisticated, and probably expensive, and the quality of the work will be evident when examined.

-

Yanagi has some interesting and helpful observations and stories, however, there are some of his speculations about the history of the objects, and who made them and why, that I think should be treated with skepticism. I fully agree that to appreciate the Japanese aesthetic principles being discussed, that it is very important to understand the cultural context. This would be late Muromachi to Early Edo Period Japanese culture. The cult of Cha-no-yu or Tea, as it developed during this period is a key element. Buke culture, particularly in the area of esoteric or spiritual beliefs and practices, is also important. Having read most of the available writing about wabi in English, I have the impression that it is an important but slippery idea. In contemporary usage, wabi is often confused or conflated with sabi and is now a trendy term, wabi-sabi. What is meant now by wabi-sabi I think is different from the 16th Century Japanese usage of wabi. One must be aware that the history of tea has developed many layers over 450 years, so something of an archaeological approach is needed to separate out what was happening by time period. Many confuse later developments in the philosophy of tea with earlier practice. Many descriptions of wabi and wabi-sabi in the current marketplace of ideas are vague and contradictory, and are often co-opted in an effort to sell something, such as interior design. The typical descriptions in English have an over-emphasis on appearance, and vaguely dance around how something has the look of, or symbolizes, “humility”, “melancholy,” imperfection”, “impermanence”, or “insufficiency” to list a few commonly used words. Wabi is sometimes described as a style or a characteristic, but, 16th Century Japanese wabi was really Buddhism, which is a practice, rather than appearance or posing, and in order to understand it, it is useful to examine the larger social implications in 16th century Japan and how it was applied culturally. In my view, wabi (at the time) was a Buddhist Way of Being, and was primarily an ethic rather than an an aesthetic, although it had aesthetic impacts. This ethic of wabi informed the Tea Master’s material choices, and we can see that in the design of their tea houses, gardens, and utensils. I think examining wabi as an ethic makes it easier to understand wabi aesthetic choices and provides a deeper and richer meaning and context. Old Japanese words that are more specific to study in terms of wabi are wabicha (poverty tea) and wabizumai (the wabi way of living). These words imply that wabi was something one practiced, rather than what something looked or felt like. Ethically, the question is why was this wabi method of tea developed, and, what for? The prominent people in the wabicha movement such as Jo-o, Sogyu, Sokyu and Rikyu were dedicated and accomplished Buddhists. All of them were in business as Tea utensil dealers and teachers of esoteric Tea ritual. They created an inclusive tea (Soan Tea and later, Wabi Tea) as a Buddhist Culture of Awakening within the Machi-shu class. The practice of an art as a Buddhist path to enlightenment or "way" (do or michi) is a well understood application among the Japanese martial arts. Judo, kendo, and kyudo are examples. Recent scholarship on the sociology of wabicha focuses on its ceremonial or ritual function, such as in the work of Theodore Ludwig and Herbert Plutschow. The earlier form of the Tea ceremony, or Shoincha, as practiced primarily by the Ashikaga, used the tea ritual to assert dominance and hierarchy. It had a confirmatory purpose to impose social order. Ludwig and Plutchow make the case that the goal of the Buddhism - oriented wabicha experience was transformatory; to break down the barriers of suspicion and distrust between rivals and to allow them to get to know each other as people. In modern corporate-speak, this was like a “bonding and team building” transformatory experience to promote unity among the Japanese, particularly those of rival clans and different classes. What was valuable to the Tea Masters about the material objects - the construction of the ceremonial space and the choice of utensils - was not their rarity, or importance, or cost, or desirability, but how they harmonized and related together to support this transformatory experience. There is a similar sense of these wabi - Buddhist values that we see in some sword fittings, especially tsuba. What wabi tea innovated was a commonly understood visual language to to express wabi ideals. This visual language was applied to many aspects of Japanese material culture and indicated an accomplishment of cultural refinement and taste. So, yes, read more books if you want to understand how wabi aesthetic language relates to sword fittings. Here are some suggestions. Japanese Art and the Tea Ceremony Rediscovering Rikyu Japanese Tea Culture Cha-No-Yu Turning Point Tea in Japan A short introduction to a Japanese martial art (and other arts) as a Buddhist Way, is Zen in the Art of Archery by Eugen Herrigel. On the topic of Buddhism, and its views on materialism and the proper way of living, I find the works of Stephen Batchelor to be helpful. Tim Evans

-

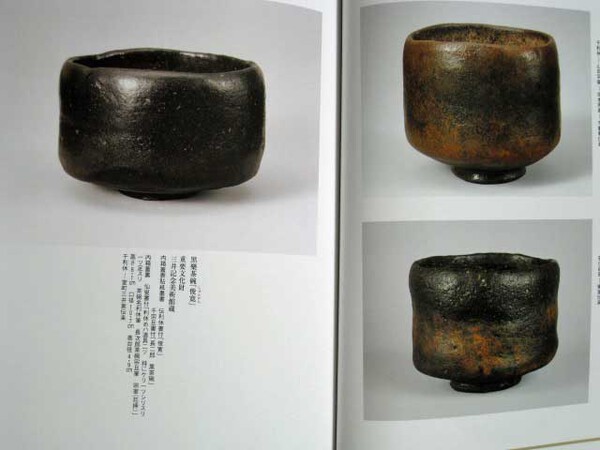

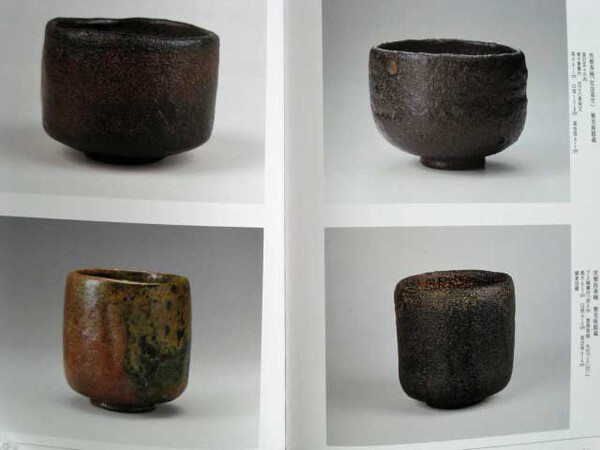

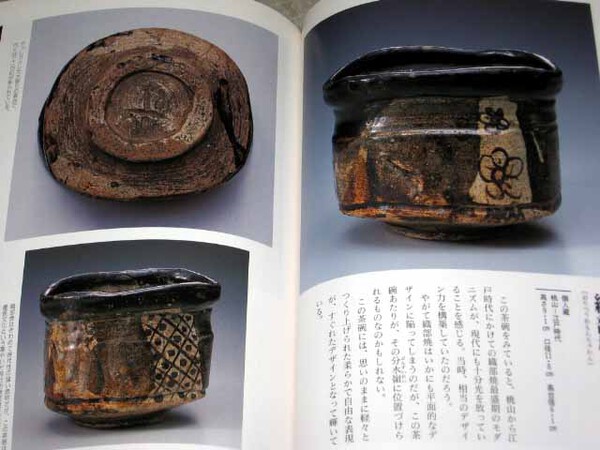

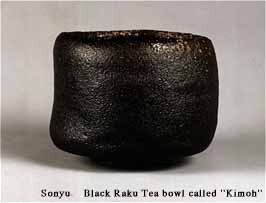

Here are some examples of important masterwork tea wares that show similarities to YKB and other Momoyama - Early Edo period tsubako such as Nobuie and Hoan. It is thought the pottery came first, and was developed as a unique aesthetic style that complemented and reinforced the intense experience of the Soan, Wabi, and Daimyo forms of cha-no-yu. The practice of cha-no-yu went 'viral', as we say today, in the Momoyama period, and was embraced by all classes of Japanese. Read about the great Kitano tea gathering for example. Because Buddhism was of vital interest to both the Tea Master and the Warrior, it is not surprising that the unique visual language developed for cha-no-yu crossed over into tsuba.

-

Hi Steve, You had mentioned above learning about Momoyama and Early Edo Buke culture and specifically their practice of Cha-no-Yu, so I thought I would offer up a bit of a book list. Rediscovering Rikyu: https://books.google.com/books/about/Rediscovering_Rikyu_and_the_Beginnings_o.html?id=vkqBAAAAMAAJ Japanese Tea Culture: https://books.google.com/books/about/Japanese_Tea_Culture.html?id=VmTqCB9TBXYC Turning Point: Oribe and the Arts of Sixteenth-century Japan: https://books.google.com/books/about/Turning_Point.html?id=q50bU2oPj98C Tea in Japan: https://books.google.com/books/about/Tea_in_Japan.html?id=O8MjO6U62xgC Japanese Tea Ceremony: https://books.google.com/books/about/Japanese_Tea_Ceremony.html?id=pS_RAgAAQBAJ These last two are probably the best overview titles. Some of these are out of print, so your local library might be able to find a copy. >My belief is that one cannot properly appreciate or understand Yamakichibei guards unless one also studies the culture of Tea in the late-16th and early-17th centuries.<

-

Thanks for the compliment. I have been experimenting lately with the scanner and thought the images were good enough for posting.

-

-

-

-

-

Thanks Brian, An interesting signature variation that needs more research. I agree with Bob Haynes that some of the tsuba signed this way are very good and have some age to them, and so are worthy of study.

-

-

> would be most appreciative if anyone would help me out with a mon question as I do not currently have any references on this subject. I would like to know the families who used the Tachibana mon depicted here: Pete, Chapplear's book lists the following families using this particular form of the mon: Obayashi, Sekiyado, Udagawa. Kindest regards,

-

Some observations: What is meant by the term "hidden cross" fittings are in reference to the type of fittings posted by Mike Y. There are many tsuba with quadrilateral symmetry that look vaguely cross-like, but any resemblance to a Christian symbol is coincidental. There are, as posted by George, many fittings with the Jumon (Japanese number 10) as was used by the Shimazu Buke of Satsuma and some others. The Shimazu Daimyo were definitely not Christian, and their use of the Jumon predates the arrival of Europeans. There are tsuba and other objects that date from the "Christian Century" in Japan (1549-1650) but they are very overtly Christian, and there is no question. Here are some images from an exhibition catalog. I don't agree on two of the tsuba. Another tsuba with a Christian motif. I have not seen it in person, so I can't attest to it's age. Tim Evans

-

Hi Patrick, Instead of focusing on Zen, look into Japanese Buddhism in general, as there were Bushi that practiced other forms of Buddhism such as Mikkyo and Nichiren. The place to start is to consider the time periods when Buddhism was culturally dominant. In regard to the tsuba that you can find, this would be the Muromachi, Momoyama and Early Edo periods. Later on in the Mid to Late Edo periods the dominant influence was the Neo Confucianism instituted by the Tokugawa, so you will not find as many Buddhist influenced tsuba from those periods. There are a lot of tsuba with Buddhist subject matter such as the Wheel of Law, Temple Bells, Cha no Yu utensils, etc. that are about Buddhism, but then there are also tsuba that are Buddhist, in that they demonstrate Emptiness (Ku) – by expressing Process, Relationship and Transformation; and so they are intentionally ambiguous, contradictory and incomplete. This attempt to express a Buddhist view of reality by adopting the visual conventions developed by Cha no Yu Tea Masters is where the Kanayama and other “Tea” type tsuba of the Momyama and Early Edo periods come from. Some further reading on Cha no Yu and Ku http://www.anthropoetics.ucla.edu/ap0501/tea.htm http://www.stephenbatchelor.org/index.p ... tmodernity Tim Evans

-

Hi Ludolf, Thank you so much for the reference! Kindest regards, Tim Evans

-

I am hoping someone who has a Naughton Collection Catalog can look up an entry for me. I have an unsigned tsuba, and I remember seeing a very similar if not identical signed example in the Naughton book in the Sunagawa section. I also recall that the catalog number for the picture and the text entry had some of the digits mixed up, but was not hard to figure out which text went with the picture. If the tsuba can be located in the book, then I would like to get the text entry and page number to properly document and attribute the tsuba I do have. Kindest regards, Tim Evans

-

The characters in the tsuba in question are "shu". See Nelson's Character dictionary #285. It means master, main principal, important, head of house, lord, etc. Can refer to a person or an idea. Sasano mentions it also means cinnibar. See M. Sasano's silver book, page 139. The character in the tsuba at the top of page 2 is not "ho" but "fuku", Nelsons #3741. It means serve in the military or discharge duties.

-

It really comes down to individual taste. Personally, I prefer them cleaner, however, there are others who like them grungy as it makes it more "antique" looking (see tks3 from my previous post about "curio lovers"). To answer your question, I can't tell from the image if there is a problem developing. As this is probably among the top 10 most important known tsuba, doing anything to it is probably fraught with political implications. You might recall the controversy over the cleaning of the Sistene Chapel ceiling. Many objected, and much scholarship was undone as it was discovered that Michaelangelo's work was not as dark, mysterious, tortured and moody as some wanted to believe. This interpretation was entirely due to the dirt, wax, smoke and over-painting covering it up. That said, it is possible to over clean a tsuba. It should have a sense of age and elegance. It takes practice and judgement to conserve a tsuba - I see it as being the equivalent of polishing a sword. However there is no formal apprentice system to teach people how.

-

There are problems with museum collections. Tsuba are considered "minor decorative arts" so they are a very low priority for any kind of care or attention. Some of the issues as follows for collections I have seen in the US: * Frequently uncataloged so pieces can go missing * No funding for training someone on proper conservation * Sometimes cleaned by well meaning but misguided individuals. There are some horror stories about what happened to the Gunsaulus collection for example Important tsuba are really better off in the hands of knowlegeable collectors

-

Some food for thought from Akiyama Kyusaku with commentary by Bob Haynes. These excerpts are from the Token Kai Shi, published in the early 1900's. Originally translated by Henri Joly into French and then translated into English by R.E Haynes and published in To-Ran.

-

Austin, I am always interested in the histories behind these things. Would you be willing to share some details on how you found it? Auction? Dealer? Another collector?