-

Posts

931 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

6

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by mas4t0

-

Favorite Era for Sword Making

mas4t0 replied to Blazeaglory's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

I agree with this generally, but it does raise some questions. When commissioning or purchasing a Shinsakuto would the work sought be a pastiche (that is; a work in a style that imitates that of another work, artist, or period)? In which case, is your favourite era actually the era that the blade was inspired by? If a smith devotes his life to recreating Koto blades, and I commission a blade from him because I too admire Koto blades, am I really showing an admiration for Shinsakuto blades, or a desire for a Koto blade in original condition? This might seem pedantic, but the point I'm trying to get at is; is this a love for Shinsakuto or would we feel the same way in any other era if we were living contemporaneously with it? -

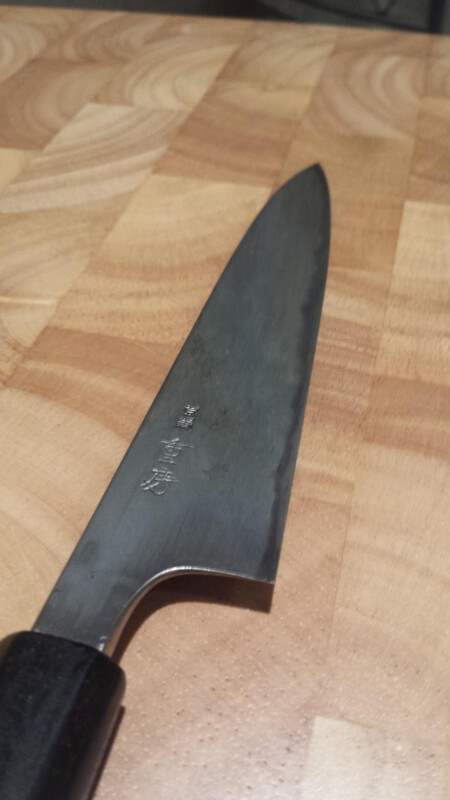

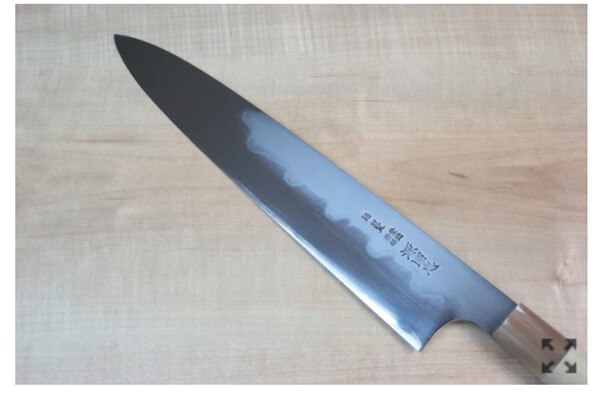

I think in many ways that the historical constraints are still relevant and the effects are still visible. The qualities of the available blades directly influenced the technique of the trades that relied on these blades as tools. The western approach to breaking down poultry for instance is entirely different to the Japanese approach. The knives have different shapes, different geometry, along with different levels of sharpness and durability. Today this is optional, but the two different approaches and blade styles are clearly optimisations to what was achievable, and the techniques developed have been handed down to the present day. The western approach relied more on brute force and durability of the blade (often chopping through bones) while the Japanese approach relied on sharpness and precision to cut the connective tissue and separate at the joints without breaking any bones. One is more similar to a hand axe while the other is closer to a scalpel. All my vegetable knives are Japanese, but I use only western style butchery knives as I lack the skill that the Japanese knives require.

-

I know that in Battodo, they recommend two mekugi, one of brass, for safety reasons. I'm not sure if there is any historical president for the use of brass, but it does seem like a reasonable thing to do as an extra level of security. An extra piece of bamboo isn't going to make much difference overall, unless the sword is so poorly maintained that one of them drops out. Of course, additional mekugi ana could exist in the nakago for a number of reasons, and the nakago ana alone do not imply that a blade was mounted in this way.

-

I was thinking about the edge failure method. I have a mizu honyaki (differential heat treated with water quench) kitchen knife made from shirogami #2 steel; which is a very pure low alloy steel, but with 1.3% C. It's claimed these are left in the range of 65HRC even after tempering, it's very brittle. It takes an extremely acute edge and holds it very well, it'll fall straight down though soft tomatoes under its own weight, but a touch on a cow bone could cause a chip. Horses for courses. I have some other knives which are claimed to be in the low 60s, and they are more durable but still lose sharpness by chipping chipping rather then rolling. On the other end, German knives are often ~58 HRC and generally experience edge failure by deformation (rolling) rather than chipping. It seems like edge failure methods for kitchen knives transition from rolling to chipping at around 60 HRC though these are different steels so it's only a rough estimate and could be a few points off. Of course the edge geometry and usage cases are very different, but I would presume that this pattern would hold on other blades as it's a matter of the material properties of the steel. The Japanese didn't hone their edges between sharpenings as far as I'm aware, while the British at times did so daily (as is best practice with European kitchen knives too). What are your thoughts Steve?

-

He's tiny! How big is the little guy?

-

Thank you Jean.

-

Thanks Jean. I was surprised by the 45HRC result, but hadn't seen any other results from practical testing. The first study offers 0.55% C, 0.40% C and 0.20% C respectively. So if we take the cutting edge as being somewhere between 0.55-0.8% C, that should make it quite similar to 1050, 1075 or 1086, which all make good monosteel swords for practical use. The claimed 6 GPa would put the edge at 57HRC, while the HV 866 mentioned elsewhere would put it at 63HRC. I see that they state 770-850 celcius for the quench, but I don't see any mention of tempering, am I missing something or did they not temper the quenched sword? It seems reasonable that the 63HRC would be from the quench and the temper drops it to 57HRC, but I see no mention of tempering. Thanks again.

-

Are there any reliable details known about the range of carbon content for the finished shigane, kawagane and hagane respectively? Do we know any specifics on the target tempering temperature for Nihonto (or any info on the amount variation) or any range for the hardness of traditional blades after heat treat? I remember reading that testing had found 61 HRC at the edge on an untempered Nihonto immediately out of the quench, and I think 45 HRC on the edge of a tempered Nihonto. I don't know how worthwhile these numbers are as it's a tiny sample size. I've also seen a metallurgical analysis, but again, as I recall, it was only for a single blade.

-

It wasn't meant as a correction, just a clarification.

-

I've not heard before that the mail and plates of Japanese armour could be cut with the blade edge. If that's the case, wouldn't it make the armour somewhat redundant?

-

Do any primary sources detail objective criteria (beyond checking for flaws) by which blades for average bushi were visually assessed in the past?

-

At the time of the account provided by Dave, the days of full plate armour were long in the past. At most someone may be wearing a breastplate, but I don't think these were standard issue for the British. That is to say, clashing against plate armour was likely not a primary concern influencing the design of British swords at that time.

-

Thanks Dave. It's always good to see it in primary sources from the men who experienced these things first hand.

-

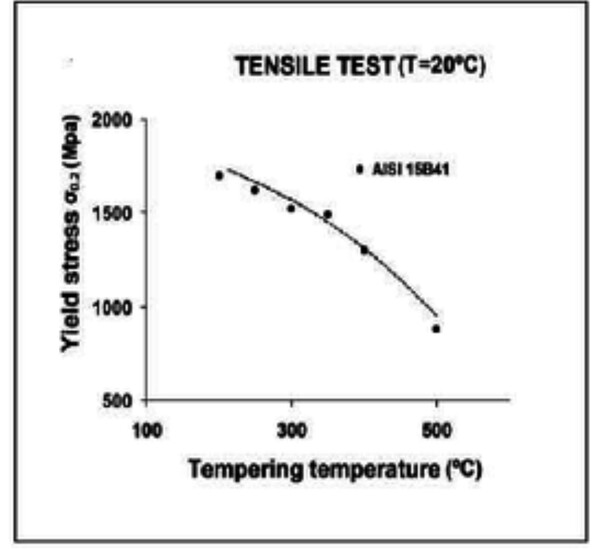

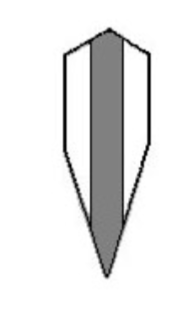

More durable, less sharp, poorer edge retention. This is well documented by historical sources. The British marveled at how the Japanese blades retained their edge, while their own sword needed 'sharpening' (though more likely honing) daily in order to cut well. A lot of this is likely down to metal scabbards, but the accounts speak for themselves. The same is true today for kitchen knives. European style knives (Wusthof, Henckels, etc) are considered by many enthusiasts to be 'beaters'. They'll take a lot of abuse, but they won't take or hold a great edge. Traditional Japanese knives are the opposite. While a Western knife blunts by edge deformation, a Japanese knife losses sharpness by micro chipping. I use these as comparison as both are rooted in their local sword making tradition. The difference is related to the hardness and thickness of the edge. For a given steel, it can usually be assumed that with 'good' heat treatment, hardness and durability are inversely correlated. This in a nutshell is what takes place during tempering, where hardness is reduced in exchange for toughness. The same is true for tempered glass, it's softer so scratches more easily, but is much more durable and less brittle than untempered glass (look up Duralex if you're interested). Edit: Graphs added for clarity. You'll see how HARDNESS and STRENGTH correlate, while TOUGHNESS is inversely correlated, so it is always a compromise between them. All of these material qualities are important in a sword and lamination allows you to make separate optimisations for the cutting edge and the body of the blade. Hardness and Toughness Vs Tempering Temperature Strength vs Tempering Temperature

-

Lamination creates a composite material. Composites allow you to combine materials, to make the most of each respective material, rather than accepting a compromise between the two. With more complex lamination, you have more fine grained control over the resulting properties and they are combined more effectively. I think that in the case of Nihonto, the major benefit is slowing crack propagation, as mentored earlier, resulting in bent blades rather than broken ones. The hard steel has the highest resistance to bending and the best edge holding, but is most prone to cracking, and once a crack is formed it'll propagate all the way through the layer quite quickly. When the crack reaches a softer layer, the crack will not propagate as readily through that layer, so the sooner you reach a lower carbon layer, the sooner the crack is halted. The issue though is that without a decent amount of high carbon steel to provide strength, the blade will bend much more easily. Additional layers allow both of these factors to my more fully allowed for. This is difficult to put down succinctly, material properties alone make up a whole course of an engineering degree and any of the textbooks on composite engineering run ~500 pages, so a full explanation is beyond the scope of a few forum posts. To illustrate the point, consider modern composites: A. Carbon fibre composite Carbon fibres have an exceptional tensile strength to weigh ratio, but no compressive strength. As fibres, they buckle under compression. As such, they need to be combined with a resin to bind them together, give them structure and provide compressive strength. B. Steel reinforced concrete This is much the same mechanically. Concrete is strong in compression, but weak in tension, while steel is the inverse. In each of these cases, the ratio of the two materials and the way in which they are combined is of the utmost importance. Also consider an oil painting. The paint will crack over time, but the cracks do not propagate through the canvas.

-

With regards to the san-mai lamination illustrated above, it is a common Japanese lamination technique, it's the standard for traditionally made double beveled Japanese kitchen knives for one. I believe it's also standard for traditional Japanese axe heads.

-

Thanks Steve. That's all I was trying to express. I didn't realise that people were using 'san-mai' to refer to any other lamination than the one illustrated. Is san-mai being used to refer to anything with 3 layers (irrespective of arrangement) or is it being used as short hand for lamination in general? I was never meaning that the high carbon steel would be completely encased, rather that it was clad by iron. I can see the need to jump in and straighten things out if it read like I was suggesting a kind of inverse kobuse lamination (with the hardened steel serving as the core). I'm glad we straitened that out.

-

Ken, I don't see what I've said that's pedantic. The comment above was in reference to this, it does seem that Steve was saying that swords are made that way. Is there disagreement over what is meant by san-mai? Are we referring to the same thing; three layers with hagane in the centre and shigane on either side laminated as shown in the image?

-

Steve, san-mai as a lamination style is not one we see in nihonto, honsanmai yes, but not san-mai, it is a technique traditionally used on knives. I don't see what's contentious here, do we have a different understanding of what san-mai means?

-

If there's anything specific you take issue with, let me know and I'll clarify. Are you meaning unhardenable (shigane) cladding, but with a sufficient amount of the hagane exposed to fully show the hamon? Any examples?

-

To be clear, san-mai blades do not show a hamon. They show a line where the unhardened cladding meets the core steel. A hamon specifically delineates between martensite and pearlite microstructures of heat treated steel. A cladding line is simply a delineation between the core of hardened steel and unhardenable iron or stainless steel that has been used as cladding. The core steel (which constitutes the cutting edge) is heat treated exactly the same all the way through from the edge to the spine, while the cladding is unhardenable and does not respond to the heat treatment. It is impossible to show a hamon on a traditional san-mai blade as even with a differential heat treatment, the hamon would be hidden under a layer of unhardenable iron. This is done for a few reasons, but a key one is that soft iron is easier to work after the blade has been heat treated. Many Japanese knives are worked with draw knives to give concavity and convexity to the blade faces. There are traditional Japanese kitchen knives with a hamon. These are monosteel knives, and are differentially hardened. They are only generally recommended for professional use as they are much more brittle and prone to chipping then standard san-mai blades. Some examples: Shigefusa Kasumi (san-mai) Petty Mizuno Suminigashi (san-mai with the cladding layers folded for aesthetics) Gyuto Mizuno Honyaki (differentially hardened monosteel) Gyuto

-

There are examples of European swords that show a hamon when polished appropriately. I've seen a German blade from I think the 12th century which showed a hamon. No idea what techniques caused it to manifest in the blade.

-

I was looking on Keith's site just a few days ago. I never spoke with Keith directly but I felt like I got to know him somewhat after reading a few hundred of his posts over the years. Very sad news.

-

Thanks Brian. I expected that response.