-

Posts

3,046 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

73

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by paulb

-

I recently revisited an article I wrote some years ago discussing whether buying a sword from the second war was the best starting point for beginners. I have discussed it with Brian and we agreed that it might be better placed as a topic for discussion rather than posted in the article section. So at his suggestion I have copied the text below and created what I believe to be the longest single post in the history of the board so far! Collecting Japanese swords from the second world war As is often the case I need to start this with an apology. I do not collect swords from the second war nor have I bought one for more than 25 years. I am therefore ill qualified to offer advice, recommendations or opinion about them. The thinking behind the following started as a result of various conversations I had during and after the NTHK shinsa held in November 2008. The NTHK held its second UK shinsa in November 2008. During the two days of the event more than 200 swords were submitted to the panel for appraisal. It was notable that a large number, possibly even the majority dated from the second war. What also became apparent was how difficult it is to differentiate between swords made using the various methods employed during that period. I believe the vast majority of collectors start by buying a Showa-To. They are not uncommon and generally less expensive than alternatives. There is also the optimistic hope that we all have at the beginning of our collecting careers that the one I am buying is a hidden treasure, an heirloom from a noble family mounted in Gunto mounts and carried in to war. Such blades do exist and have been discovered. However these are extremely rare finds. This ambition is fed when touring arms fairs or scanning eBay where virtually every blade offered by the non- specialist dealers is “an old family blade”. In fact based on these descriptions it would seem that virtually all swords in the war contained old blades which leaves one wondering what the military production forges actually did in the 1930s and 40s. Some 35+ years ago I bought my first Japanese sword. It was a Showa-To in bulk standard Gunto mounts. I was lucky at the time I bought it as it was just before we started to see the influx of Chinese, and at that time, Pakistani fakes hitting the market. I knew nothing when I bought it, other than I liked what I saw and was fascinated by the Samurai culture and Japanese art. I kept that sword for many years trying to prove to myself that it was an early Mino blade by Kanesada. It was, I think, made by Kanesada working in Mino during the war years. Listed in John Sloughs book he made medium and low grade Gendai-to. The reason I mention this is that although the vast majority of us start this way I believe it is the wrong thing to do if your primary interest is traditionally made Nihon-To. Let me qualify that by saying that there is absolutely nothing wrong with collecting Gendai-to, Gunto, Naval swords or whatever you are interested in. What I am saying is that it is not the best way to start. During the Showa period more methods of manufacture were employed simultaneously than at any other time in Japanese sword making history. Swords were handmade, partially handmade fully machine made, made using traditional material, made using imported raw material, made using imported steel. They were water quenched or oil quenched. Some have traditional hamon some have etched hamon some have polished hamon. The fact is that identifying whether a sword is made using traditional material and methods is extremely difficult, especially if it is in less than perfect polish, which the majority for sale are, and if you are relatively new to the subject. In fact even those of us who claim many years of collecting experience can and do get it wrong. In Fuller and Gregory’s second book on Japanese military swords they claim that less than 10% of the officers swords surrendered held traditionally made blades whether family pieces or Gendai-To. This means that 90% were either partially or fully machine made. Japanese arsenals were producing blades from 1925 until the end of the war. At their peak the arsenals in Seki and Tokyo were targeted with producing 30,000 blades a year. By the latter years of the war this number had declined to approximately 8000 blades. According to Fuller and Gregory’s calculations some 350,000 swords were surrendered at the end of the war. If you add to this those that were confiscated by the occupying forces and those destroyed during the conflict in the field straight afterwards the total number of swords carried by the Japanese military was probably nearer 1 million. Of this number approximately 8000 were made at the Yasukuni shrine between 1927 and 1942 and a lesser number at the Minatogawa Shrine which produced Gendai-to for the navy for 4.5 years. They go on to define 9 different methods of manufacture including handmade, partially handmade and machine made blades. For the sake of consistency I have used their definitions when discussing the different types of blade found. I have also tried to offer definitions for some of the broader terms used. : 1. Showa-To:- A sword made during the Showa period between 1926 and 1945. Most commonly the term is used when referring to machine made blades produced in the 1930s and 40s 2. Shin Gun-To: Literally new army sword. Often used when describing a blade mounted in the 1934 pattern fittings that copied earlier tachi mounts. Hand made, partially hand made and machine made swords. 3. Gendai-to. A modern sword made after 1876, but more commonly referring to a blade made during the Showa period, using traditional material (tamahagane) and techniques. It is hand forged, folded and water quenched. 3a. Gendai-to made using mill steel. Produced using steel made in a western style smelter but being hammered, folded, drawn and water quenched. Western style steel is more homogenous than traditionally produced tamahagane and cannot therefore be folded without losing grain structure. Smiths compensated for this by adding carbon and folding fewer times. The resultant blades produced hada a hamon in nioi or nie and with all of the activity one would expect to see in a hand forged, water quenched blade. 4. Ko-Isshin Mantetsu-to: A sword made using imported Manchurian sand iron. These blades comprised of a soft iron core encased in a harder steel tube. They were made using complex manufacturing techniques but cannot be classed as Gendai-To. However they do exhibit a form of hada, hamon Nie and Nioi and activity within both jigane and hamon. 4a later Mantetsu-To made in Manchuria initially they may have used the same methodology as the Ko-Isshin swords but later manufacture used a single piece of rolled steel and oil quenching (see below) 5. Han tanren abura yaki-ire-to. Literally partially forged, i.e folded several times and hardened in oil. Quality varies the better examples exhibit a fine hada and nioi like hamon (but without nie) 6. Sunobe abura yaka-ire-to: A sword made from a single piece of bar steel and oil quenched. 7. Murata-to machine made from a single piece of steel exhibits a Yakiba but without clearly defined hamon. These blades are regarded as inferior to Mantetsu-to. 8. Tai-sabi-ko. Blades made from anti-rust steel primarily for naval swords 9. Machine made- produced in an arsenal from a single piece of steel which may be fully quenched in oil (tempered?) without clay coating or allowed to cool in the air. These were general issue swords such as cavalry sabres or NCO swords. With regard to quality the methods described above may be graded as follows: 1. Tamahagane Gendai-to 2. Mill steel Gendai-to 3. Ko-Isshin mantetsu-to 4.Han taran abura yaki-ire 5. Sunobe abura yaki-ire to 6. Mantetsu-to (rolled steel) 7. Murata-to The definitions above are broad and probably over simplified. However they do demonstrate the point made earlier regarding the range of production methods being employed at this time. They also hint at the vast variation in the quality of swords being made. Even within the single category of traditionally made Gendai-to there is huge variation in quality. At the top of the list sit blades produced at the Yasukuni shrine. Here selected smiths produced superior swords using Tamahagane made in the shrines smelter. Based on the lists compiled by Richard Fuller there appear to have been between 8 and 10,000 swords produced at the Yasukuni shrine. Of equal quality were those produced at the Naval Minatogawa Shrine. I couldn’t find production numbers for their output but because of the shrines shorter life and the heavy losses of naval personnel during the war far fewer of these blades have survived. By now I think it is becoming clear just how complex this field of study and collection is. Looking at the above definitions I think that, based purely on the workmanship visible in the blade it would be extremely difficult, if not impossible for the majority of collectors to differentiate between the different types of blade outlined above. When these blades are in less than perfect polish the task becomes even more challenging. Common Myths: 1. “An oil hardened blade made from a single piece of bar steel cannot produce Nie”. This is a misconception, and one that I have believed for many years. I was wrong. Fuller and Gregory confirm that impurities within the bar stock can, on occasion facilitate the formation of ko-nie. This is, however, a result of accident rather than design and the resultant nie is distributed unevenly and inconsistently throughout the hamon. Blades made in this way do not exhibit hada. Which leads to the second most common myth: 2. “It’s muji-hada”. Blades made out of bar steel do not exhibit hada. This is because there is no lamination s a result of folding and consequently no weld lines between the layers of steel. This is not Muji hada. Muji hada or “grain-less hada” refers to extremely tight hada produced by Shin-Shinto smiths where the weld lines between the layers of steel become almost invisible. In Sunobe blades the lack of hada is the result of the blade being drawn from a single piece of bar steel. 3. “Yasukuni blades are equal in quality to those produced in the Koto period”. Blades made at the Yasukuni shrine enjoy a very high reputation and are eagerly collected by specialists in Japanese military blades. What is also apparent is that the quality of Yasukuni blades varied considerably. At their best they are as good as many earlier works but there are also some that appear to have little merit with regard to hada, hamon or activity. As to whether the good ones reach the standard of good Koto blades becomes a subjective judgement my personal and very biased view is that they don’t get anywhere near the better works of the koto period. I also believe the works of such Gendai smiths as Gassan Sadakatsu were of far better quality than any Yasukuni blades I have seen. Conclusion. In the lectures published in the Solingen catalogue Nobu Ogasawara and Michael Hanegbusch attempt to persuade their readers that we should focus all our attention on “Meito” (swords with a name” and that one can only learn by studying top quality pieces under expert guidance. While these points are obviously true, such a narrow approach leaves little room for the majority of us who have neither the funds nor the time to devote to the pursuit of the perfect. To adopt such an approach would negate the huge amount of pleasure we all gain from studying and collecting and lead to the neglect of a vast amount of important historical material. However there were within these papers some very important and useful pointers. Mr. Ogasawara points out that once you fall below the highest level of manufacture it becomes increasingly difficult to differentiate between schools and traditions. By the time you get to the third or fourth level it becomes extremely challenging. In his words differentiating lesser work between Sue Bizen, Seki, Bungo-Takada etc. is extremely difficult. Consider then how much more difficult that becomes when looking at swords made during the Showa era. More swords were produced in the first half of the 20th century than at any other time in sword making history. The range in quality was huge. More manufacturing methods were deployed than ever before. In addition the majority of remaining examples are in less than perfect condition. As said above I do not believe there is anything wrong in collecting Showa period blades and many people gain a great deal from the experience and contribute a lot to the preservation of this part of the World’s history. What I do believe is that for someone starting out in the in the study of Nihon-To focussing on Showa blades is a mistake. I hasten to add it is a mistake that I and I am sure most of us have made! I believe that initial study would be better served by buying Shinto blades in good polish where all of the features that make a Japanese sword unique are visible and there is no ambiguity about how the blade was made. A reasonable Shinto wakazashi in good polish can be bought for much the same price as a Showa-To. I believe one can learn a lot more about Nihon-To from such a sword. This would then equip the collector with a better understanding of what to look for in a second world war blade if that is the route they wish to follow. Paul Bowman Jan 2009 (edited 2020)

-

Mark, Since you have been out of circulation I think the market has remained faily flat, even dropping for mid range work. As is often the case blades at the very top and very bottom tend to be fairly consistent but those in the middle (such as those you mention) fluctuate the most. At the moment the pricing is low. The downside from our point of view in the UK is that the UK pound is also a lot weaker against USD, Yen and Euro than it was four or five years ago. Ebay went through a phase of banning the sale and purchase of Japanese swords in the UK. I thought this had eased recently but have no personal experience. Shipping is definitely an issue and there is considerable inconsistency in the way the border force interpret the law. We are trying to work on it but have not had too much success so far. If you choose the right carrier and it comes in at the right point of entry it is generally not an issue provided it has the right paperwork (Tsuruta san is very experienced with international shipping) Juyo blade pricing ranges from around 20k to a much larger number. The price is governed by the maker, the rarity and the condition not the paper.

-

I think I am am a bit of a philistine when writing in this post as mei have not figured highly in my thinking when looking for a sword. In fact I have only one signed koto blade n my collection and that is a recent addition (thank you Jean) Two others have old shumei but both are O-suriage. From a hstorical perspective I fully appreciate and agree with the points made by Jussi, Kirill and Michael, however from a collecting motivational perspective I think I am approaching from a different angle. I especially like Kamakura period blades, not because they are old but simply because they are amongst the best ever produced. As said above signed works of this period are comparitively rare and therefore expensive. Because of the rarity even signed works in poorer condition can command a premium. When I look I am looking for workmanship that is beautiful and in excellent condition. To some extent who made it becomes less relevant if the other boxes are ticked and there is no question that exception mumei pieces, while expensive, can cost a great deal less than a signed piece in poorer condition. As said I can and do understand why people regard mei as so important and hunt down those rare signed works. But for others it is far from the driving factor.

-

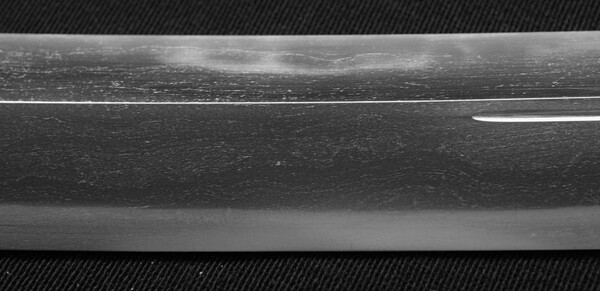

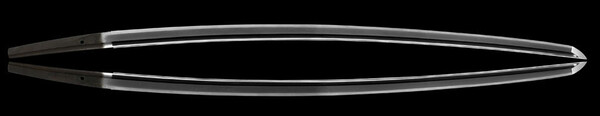

Coming back to the orginal theme and I am conscious that I don't want to bore people, but I have been playng with another blade to see if I can get more detail in the hamon and reduce glare from the shinogi-ji. I am becomng a contortionist trying to adjust angles of blade, camera and lights. Going to give it a rest now as I feel I am runing around in ever decreasing circles. But if nothing else I hope it might encourage others to have a go. If a technically challenged impatient idot like me can make progress think what you can do!!

-

I've always understood Nijuba to relate to a double line of nioi or nie running parallel in the hamon. I have not heard it to describe this form but then again I cant remember seeing this on another blade.

-

Thank you Wim I am not sure if thats where I saw it but I will certainly check it out

-

Ben This looks to be an extreme example of muneyaki. Usually you see odd patches n the mune of some swords and some smiths are more prone to create it than others. It has been considered by some to be accidental and the result of the insulating clay falling of the mune. In this case it is obviously deliberate. I am guessng someone saw some advantage in hardenning the back eddge, whether that was to strengthen, adjust shape or just because they liked the look I have no idea.

-

Hi Ken, I think I had it once but can't find it. I think it was written to use alongside the year 2000 Yamato exhbition held, I think in Amsterdam. I have to admit like most purely academic texts, it was extremely heavy going. The statistical analysis was interesting however. The main point being that in relative terms Yamato work is rare, signed Yamato work even more so.

-

Hi Jussi, Your memory is better than mine but I double checked and yes this sword was at Samurai Art Expo. Thank you for the statisitcs which I think confirms the comment from Tanobe Sensei. Something interesting from your analysis when Han Bin Soung wrote a paper in 2000 assessing 10,000 Juyo swords he said 40% were Bizen and only 150 were mumei Yamato swords. That is a very big difference from your figure of 750. As I think the majority of Yamato attributed blades are mumei I don't believe this difference can relate to signed pieces. I wonder why there is such a large difference over a 20 year period. Perhaps more have appeared or the criteria in assessment has changed resulting in more passes. ( It may be of course that his numbers were wrong, but knowing the gentleman concerned I think it unlikely, it could also be that I recorded it incorrectly [which is more likely]. )

-

Ben I feel very under qualified to offer any tips as I am still in full learning mode. If you do a search on the site there are a number of very useful guides that have been published here over the years. They make a very good starting point.

-

I think there is too much itame and mokume in it to attribute it to Hosho. The boshi is hakikake. Two things I picked up when reading about Shikkake in the past: 1. Although seen to varying degrees in most Yamato schools the tendancy for the hada to become masame as it enters the hamon is regarded as a kantei point for Shikkake. 2. To paraphrase a quotation from Tanobe Sensei "When we see a naginata that has obvious Yamato characteristics from the early Nambokucho we tend to attribute it to Shikkake" I am guessing Shikkake for some reason made more naginata and were typically Yamato in style not taking on too many other influences as seen in other Yamato groups of the period.

-

In my bad weather quest to try and improve my photography. Attached are some images of a naginata Naoshi attributed to the Shikkake school of the ealry Nambokucho. It recieved Juyo papers in the mid 1980s.I wrote about it in more detail in an article entitled "Study of a Juyo blade" some 13 years ago and this article appears in the article section here and on the Token of GB website. It is interesting when photographing it this time round I have seen so much more detail than I did a decade ago. I guess a combination of improved understanding and experience and better photography. (getting there but still working to improve it!)

- 21 replies

-

- 16

-

-

Well done Ray, I must try this (overcast,actually pretty girm and miserable days, are something we have a lot of at present).

-

Great Work Uwe If this is the sword I think it is we have spent some time looking at it not too long ago. It's interesting and as said your video is excellent but the one thing it did for me was to highlight the difference between seeing an image and seeing a blade in hand. While I appreciate all the detail your images illustrate they dont generate the awe or emotional response the blade did when I held it. Of course this may not be the same blade and I am totally out of step, or maybe just becoming an aging hippy. The image below is me looking at the sword and trying not to cry! (Image also by Uwe)

-

I can understand why you might have gone for Kongohyoe but I had one many years ago and the hada was coarser and the shape more robust. I am wondering if this is a lot later than first impressions suggest. The ara-nie reminds me a lot of examples I have seen on Satsuma blades. Also the visibility of the hada within the hamon could point that way. The shinogi-ji looks to be masame or is that a trick of the light?

-

Kirill, I dont know what this is but am very curious as to what I am seeing on the mune. The almsost snakeskin look of thesteel is it ara-nie or something else going on?

-

Does polishing absolve all sins?

paulb replied to Northman's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

-

Does polishing absolve all sins?

paulb replied to Northman's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

The Ko-wakazashi by Yasumitsu described in a paper in the articles section and now residing in the Royal armouries, was written off by two very expereinced collectors. They urged the then owner "not to waste his money on trying to have it polished." In the words of one of them it had been used as a kitchen knife, then a garden tool and then played with by grandchildren “ it looked like a blackened blade from a pair of serrated garden shears”. Thankfully the original owner insisted on it going to Japan and being polished by Kotoken Kajihara and the result is fantastic. -

I must admit he is a smith that falls well below my radar. If this is an example of his workmanship he shouldn't. I must spend some time looking at him. I would be interested as to why the combination you mention points specifically towards him when it would seem to fit many of the others suggested here. There must be something that pushes the attribution that way beyond what is being described. Time to get to the books again!

-

Katana by 1st Generation Tadayoshi?

paulb replied to tbonesullivan's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

There are a lot of gimei Tadayoshi blades. He was a very good smith and has been continuously popular. The mei on your blade looks close to other examples seen but to be more confident it would really need to be submitted for attribution and before doing that it would need to be polished. The kissaki is a concern although it doesnt look too bad Hizen jihada was always thin so polishing to remove any deep pitting could expose core steel. Personally I am a little concerned about the shape and more particularly the hi which does not look particularly well cut. Overall it could be worth a punt. -

I think Michael has a very good point. Based on the "If your first vote is Yukimitsu and is wrong go for Taima" I think that would be a very credible alternative. I am avoiding mentioning Norishige, it just looks too quiet for him

-

Wow, Now I am on the back foot. All the masame becomes so much clearer on the uncompressed image. I need to look more carefully and take more time, but at the moment this has a Hosho look to it with the prominent masame. Not sure about the thickness though Thanks it has got my mind ticking and will make me look at references harder (which is one of the main benefits of dong this type of exercise!)

-

I like that a lot very tight hada and very bright nioiguchi. I am tempted to go for one of the top three Shintogo Kunimitsu Awatagushi Yoshimitsu (would expect to see more larger itame together with the tight ko-itame) or Yukimitsu I really like the shape. The kick in the nakago adds an incredible extra somethingto the overall appearance A good looking piece. thanks for sharing

-

Hi Kirill, Thank you for having a go. I am experimenting all the time trying to capture the fine detail within jigane and looking at supposedly typical examples of a given schools work. The truth is that unless it is something bold and striking as in the 3rd sword it is very difficult to judge and images can be very misleading. The one thing I often fail to take in to account is scale. The images are often greatly maginified and this can dramatically effect perception. I have listed the answers below: Sword 1. Very fine ko-itame interspersed with a great deal of minute ko-nie and chickei. This is classic Nashiji hada of the Awataguchi School. The blade is one of only 7 daito attributed to Awataguchi Norikuni. Sword 2. A combination of ko-itame and mokume interspersed with jifu and ko-nie (jifu cant be clearly seen in images and is very faint blade in hand). This is Chirimen hada of the Aoe School. The blade is attributed to the Chu Aoe of the late Kamakura Sword 3. You were spot on. This is a combination of itame, nagare and mokume which is very clear and strong. It is classic hada of Oei Bizen. This is the Oei Yasumitsu discussed in recent threads. I believe itis the work of the Shodai which would place it in the late Nambokucho. Sword4: For a long time this was believed to be Rai, probably Rai kunimitsu. Most recently it was papered to Enju. The hada is very tight ko-itame with a great deal of ji-nie. It compares very favourably with many Rai blades I have seen. The distinguishing features that lead to Enju are the O-maru boshi and the fact there is no nie utsuri which one might expect with a Rai Kunimitsu.