-

Posts

241 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Yukihiro

-

On another note, out of the 25 gendaito in Army shin-gunto mounts recorded in Leon and Hiroko Kapp & Leo Monson's book Modern Japanese swords: the beginning of the gendaito era, only 9 (36%) had a family mon, 4 of them with a general's tassel, 4 with a field grade tassel and only 1 with a company grade tassel. My understanding of how tassels were bestowed upon these swords is that mon-bearing swords are generally felt to be those of higher ranking officers. To be sure, some of them may have been original to their swords

-

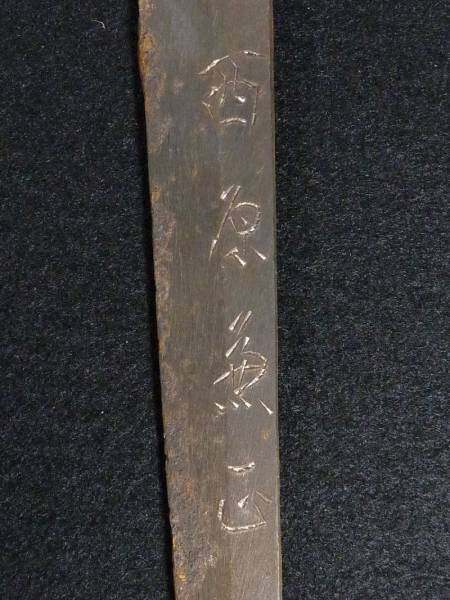

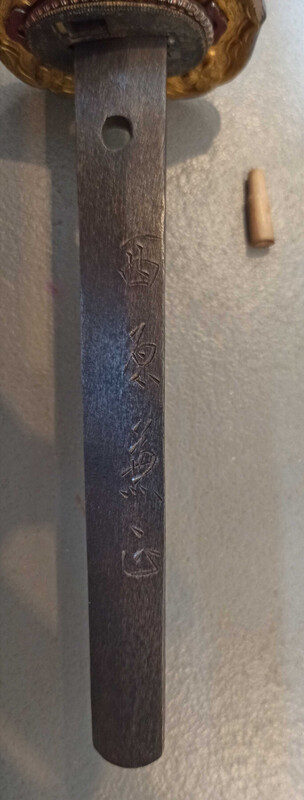

As I have made it a habit of reviving older threads, here is my personal addition to this one: an Amahide daimei blade with a prominent Seki stamp. The mountings must have had eight seppa originally and have a clasped hands sarute together with a mon on the kabuto-gane, so there is every reason to believe that the WW2 owner of this gunto was willing to spend money on his koshirae to make his sword look the thing. There is always the possibility that the mon is a later addition to this showato, though.

-

This hurts to see. WARNING! Graphic images of a ruined Emura

Yukihiro replied to DTM72's topic in Military Swords of Japan

"Bare blade" is, I daresay, an honest description of that Emura -

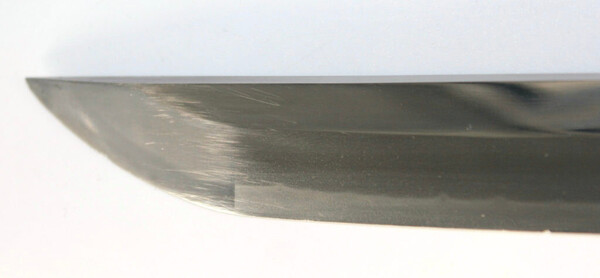

I know this is an older thread, but I have yet another question about oil-quenching techniques: were there ways for gunto-smiths to make the hamon on their oil-quenched blades look closer to a water-quenched hamon? The reason why I am asking is that the hamon on my Amahide gunto does not look strikingly oil-quenched to me, although the tell-tale darker patches do seem to appear on some of the pictures. In other words, the question I am asking is whether there were any technical possibilities for gunto-smiths to tone down the oil-quenched aspect of their blades.

-

The mon was identified as Daki Omodaka (抱面高), but I am at a loss as to the family or families it might stand for. The only information I have found so far is that the Daki Omodaka mon was used by the Mōri clan (毛利氏) that governed over the Chōshū Domain (長州藩) from 1600 to 1871.

-

Some more information about Fukumoto Amahide's production: Cabowen explained the phrase daisaku daimei : "daisaku means made by a student for the master and daimei means signed with the master's name with his permission by his student. Thus, a daisaku daimei blade is a work made entirely by a student in his master's place...." (https://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/8258-assastince-please/#comment-83023)

-

The pictures aren't mine: they're the seller's, actually. I shall try to take closer views of the blade when I receive the gunto, though.

-

From what I have understood, Amahide(天秀), whose civilian name was Fukumoto Hideyoshi (福本秀吉), had a workshop or factory where several gunsmiths were at work so that there is little chance that this blade, although signed with his name, was by his hand. I would say this sword exhibits typical Showa-to characteristics save for the mon which was affixed to its tsuka and the rather elaborate sarute. One of the eight seppa is missing and the saya was rather badly damaged at some point. The Seki stamp is clearly visible, so there is no doubt this is not a gendai-to. I would tend to think the ito is not the WW2 original one but would need the opinion of the more knowledgeable forum members to confirm that. Other than that, I would be interested to know whether the number (?) painted in yellow on the nakago does tally with the numbered parts of the koshirae. My first impression is that it doesn't, so maybe the koshirae is not quite original to the blade.

-

I'm into WW2 British & Canadian uniforms (D-Day and Battle of Normandy) and ancient coins (Celtic and Greek coins from Italy & Sicily), plus I have quite an extensive collection of .22 LR military training rifles (German KKW & DSM34 Mausers, British No. 2 Mk IV* and No. 8 Mk I Enfield rifles, French MAS 45 training rifle...).

-

What I would be interested to know is what such a wartime polish looked like just out of the workshop.

-

I want to thank Chris (Vajo) for his expertise: I am always amazed at how accurately he can make out the smallest details in a sword. Thank you for your time and your keen eye, Chris!

-

That makes sense, Bruce. I hadn't thought of that. But what about the copper seppa with two slots in it? My initial thoughts were that whoever re-used the seppa must have cut a second slot to adapt it to the (bigger) lock pin. PS: on second thoughts, maybe the slot was cut on the wrong side of the seppa so that another one had to be cut

-

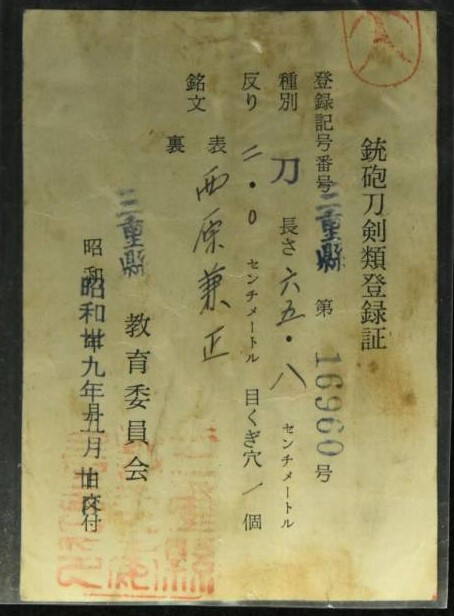

I have just found yet another instance of a Nishihara Kanemasa sword complete with registration certificate - I assume that the fact that his blades are not Seki-stamped made it easier for their owners to get a certificate, as this one is dated March 2, 2009 : https://aucview.aucf...om/yahoo/s525185855/ The sword, which is in kai-gunto koshirae, is termed a gendai-gatana (現代刀). Its mei is again exactly the same as those we have seen before, which leads me to believe that, although Nishihara Kanemasa is among the most obscure of WW2 Japanese swordsmiths, he was by no means the least prolific of them all. I don't think the sword I have on order is a gendai-to, though: to me, it looks like its blade was oil-quenched. I have the definite impression that the blade isn't in its original koshirae: the point where the seppa and the habaki meet shows a gap and the seppa are an uneven number: 7, instead of 6, but I can live with that

-

Hopefully I will get a reply - this is the very first time I am trying to contact him.

-

I had requested the seller to look for the tell-tale Seki stamp, but he couldn't find any. That does not mean per se that this is anything more than your usual showa-to, but I suppose the fact that Nishihara Kanemasa did not work at Seki is reason enough for the Seki stamp to be absent. The closest thing to a stamp I have seen on the blade so far is this punch-like hole, but it might as well result from an accident.

-

I have sent a message to Ohmura-san this morning to enquire about Nishihara Kanemasa. Maybe he will know more about him. This is the Nishihara Kanemasa sword I am ordering: I have no great expectations of it, but it looks like an honest showa-to to me.

-

That was my own feeling, as the whole speech did look quite commercial. By the way, I thought the selling of gunto was prohibited in Japan, so how come Kanemasa Nishihara's precious artwork is sold there? Is it possible for a mere gunto to get a certification paper? Maybe I am mistaken, but it seems to me that I can read Nishihara Kanemasa's name on this one.

-

Thank you Steve. This is the translation I get of the accompanying text: Japanese Sword Kanemasa Nishihara (Yoshihiro Gô) This is a very rare and precious sword, as there are very few existing swords made by Nishihara Kanemasa, a swordsmith from the Showa period, who did not revive the art after the war. This sword must have been made to protect the country with one's life. The sword has an imposing figure, and the metal is wonderfully well worked with a small itame grain. The blade is deeply boiled (sic!), and the sword was made with all of Kanemasa's strength, as if it were a sword like this one by Yoshihiro Gô. I got more or less the exact same commercial speech from another such link to one of Kanemasa Nishihara's swords. Does the fact that the term 日本刀 (nihontô) is purposefully used mean that this Kanemasa's swords were (at least partly) gendaitô? That makes me wonder why, if Kanemasa Nishihara was indeed such an outstanding swordsmith, his name was almost obliterated - was he the victim of a damnatio memoriae of some sort? The mei, at any rate, is the same, and it seems to have been carved by the same hand.

-

There were apparently no less than 8 Kanemasa swordsmiths during Showa, but I could not find any Nishihara...

-

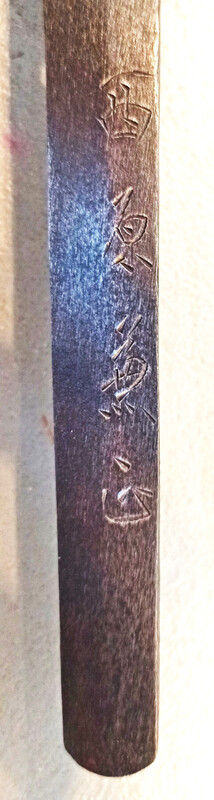

Thank you very much indeed. So I suppose the swords he made were showato rather than gendaito? There is a sword by him I am interested in, but there is no Seki stamp visible on the blade. Besides, if Nishihara Kanemasa was active in Tokyo, that might explain the absence of a Seki stamp. I have found this: XIII. Tokyo Dai Ichi Rikugun Zoheisho (東京第一陸軍造兵廠) These smiths made swords at the Imperial Army's arsenal factory in Akabane, Tokyo (1943-45). These swords are usually inscribed 'Tokyo Dai Ichi Rikugun Zoheisho'. Others may have also worked here on a part-time basis. 1. Nobutaka (宣威) 2. Kanemasa (兼正) 3. Katsunobu (勝信) 4. Morikuni (守国)

-

Hello, I have read that there had been 4 or 6 gunto smiths that went by the name of Kanemasa during WW2. Now I am puzzled because I am confronted - or so it seems - with yet another one of them: should this mei be read Nishihara Kanemasa (西原 兼正) and, if so, was he a Seki swordsmith? Regards, Didier

-

Identification of this Japanese Sword (Enigma).

Yukihiro replied to Augustus's topic in Military Swords of Japan

Thank you, Steve. I know this has nothing to do with the OP's thread but was it common for Japanese officers to write or have their names written on their swords? -

Identification of this Japanese Sword (Enigma).

Yukihiro replied to Augustus's topic in Military Swords of Japan

That is what I had thought initially, as the strokes are quite different from Toshimasa's mei on the blade, but, unfortunately, there is no telling who that Yokoda was. I would be interested to know whether other gunto have had names inscribed on that part of the blade, though - if the same name appears on other blades at the exact same spot, then it would surely be the polisher's name, although I seem to remember that the blades were polished by women exclusively at the Seki arsenal. Regards, Didier -

Identification of this Japanese Sword (Enigma).

Yukihiro replied to Augustus's topic in Military Swords of Japan

So far I haven't been able to determine why the name Yokoda (与古田) had been inscribed near the munemachi. -

Identification of this Japanese Sword (Enigma).

Yukihiro replied to Augustus's topic in Military Swords of Japan