-

Posts

3,091 -

Joined

-

Days Won

78

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Ford Hallam

-

Why?...the odd minor ruffling of feathers aside I think this has been a pretty well mannered discussion. Others may still be pondering what "it all means" and may want to offer further observations and opinions Surely it's not over 'til the fat lady sings :D

-

Hi Steve, you've seen though me!! This is exactly the tone I've been trying to cultivate myself.... It works here in South Africa Thanks again for taking the time to engage. I've appreciated your intellectual rigour I've been giving the whole matter of judging quality and artistic merit some serious though, admittedly more cautiously now thanks to the prickly issue of objectivity. I do have some initial thoughts that we might be able to build on and begin to formulate some sort of workable framework. I'll pm you with some ideas in a little while. regards, ford

-

Hi Dave, don't worry...I wasn't really taking offence at anyone's use of the term "tsuba-like-objects" as such...unless you meant mine I refer to lot's of other things by that term myself With regard to the design impinging onto the seppa-dai. As long as the design is below the actual plane of the seppa-dai so that it does not interfere with it being mounted it cannot be judged as Hama-mono or otherwise regarded as not a real tsuba. While not terribly common one does occasionally see perfectly legitimate older examples, even by big names, where the artist has taken liberties with the canvas....but still ensured the tsuba would be usable. Steve, I quite like how our "little chat" has been going :D I'll freely admit my thinking has been refined a little as a result of this debate here, with everyone's input. As I said much earlier, my opinions are always works in progress ...and I ought to have been far more specific and taken the time to lay out all my intended and implied meanings at the outset. But hey!...look at the fun we've had The word homage would probably not be used much here in SA at all really.... and almost certainly not pronounced correctly An homage in my, English , understanding would imply a certain degree of reverence and a "paying of respect" so to speak. While I have the utmost respect and love for the work of the past, even Momoyama iron, I'm not intend to be a groupie...I intend to perform in my own right. No ABBA tribute band for me.... :D As for the next exciting instalment a la your query here; and this next bit in reply to Franco; Lets get to it and see what common ground sound reasoning and clarity of articulation in our opinions may reveal. best regards, Ford

-

Pete, I was just considering the cut on the right hand side, If we imagine the blade orientation as it made that cut ( I assume the cut is less deep on the other side) it appears the handle of the attacking blade would be in the same place as the blade of the defending blade. Do you know what I mean? I'm having a little difficulty seeing how the cut at top was made too...if there were 2 long blades attacking each other. Admittedly, without the tsuba in hand...better still, on a blade and with another mounted blade with it's cutting edge correctly aligned in the cuts I'm merely speculating but I do think we need to be more rigorous in analysing the evidence. Just because it looks like it doesn't mean it is ...and those cuts still look quite hard edged for something that was apparently done so long ago...and remarkably superficial. I still can't help feeling that these sorts of "scars" are cosmetic, later additions to enhance the desirability of the items,. sorry for having succumbed to my churlish nature... :?

-

Well it does seem I've stirred up the proverbial hornets nest ...no blood loss as yet I find the example that Pete has offered quite convincing although we don't have any real way of knowing when that was done do we? But it would be churlish of me to deny the possibility that this example at least "looks" convincing. I think what would really be needed is a series of mechanical tests, tightly controlled, where a long blade weighing about 900grams is allowed to drop against various samples of metal to determine exactly the sorts of cut, and depth, are produced. This would at least bare some resemblance to objective testing of the hypothesis. Having said all that that fact that we may indeed find the odd tsuba that appears to exhibit battle damage does not disprove my original claim. That a tsuba may afford a certain degree of protection is reasonably self evident...what is being disputed my myself is that this is/was it's primary function. We can agree that almost all tsuba have a modicum of aesthetic appeal while only a tiny proportion appear to have had to serve the ostensible defensive function. It seems obvious then that the overwhelming "use" of the tsuba was to look good, the occasional tiff not withstanding. Given that tsuba you're referring to seems to have a shakudo mimi and that it wasn't cut through I'd suggest that certainly every tsuba I've ever made would easily function as well...if not better. Any disc of metal with the toughness of copper will function well. In fact it may well be that such a copper disc may be superior in terms of this purely functional aspect than a well forged and tempered, pierced steel guard. In fact I'm pretty certain of it. I'd also like to thank everyone for being so very gracious with regard to my own work, despite individual preferences. Thank you all very much indeed. I must admit to feeling quite uncomfortable though as my intention with this topic wasn't to debate the validity of my own endeavours but rather to explore what tsuba can/could mean in terms of aesthetic expression today...it was foolish of me to think I could raise this topic and not become, personally, part of it. To be honest, as an artist, I do find terms like "homage" and "tsuba like object" to be quite dismissive....implying, as they do that the pieces are somehow not real in any meaningful way in relation to the sword. That they are merely pale imitations of the forceful objects of the past. I believe I made my view clear in my initial post, that we cannot make tsuba in the same way they were made, or intended, as in pre-Edo Japan. What I was proposing was a new "function"...a reappraisal of tsuba as expressive canvas. As an artist this is what interests me and where I believe there is a valid semiotic ( to be Steve's terminology ) function. By pointing out how the apparent use and function of the tsuba has never been static...and how it's defensive function (if that ever was it's amin function ) has diminished steadily from at least the start of the Edo period giving ever more prominence to simply looking good. :D I was trying to suggest that this aspect of aesthetic expression may legitimately be continued today, particularly in relation to contemporary swords. This whole "debate" about the functionality of swords and tsuba is a complete no-brainer, in my opinion. Unless you take into account aesthetics (covers a multitude of sins) any long, tough, sharp bit of steel with a pointy end and a little disc just in front of the handle will meet the purely functional aspects of a sword. I'd suggest that many such rudimentary implements were carried as side arms on the battle fields on old Japan. To maintain that the time in which such an artefact is made in determines whether the label still applies is taking thing a bit far. The Japanese Sword has a tremendously significant cultural and artistic role in Japan today, as always. That the emphasis has shifted more towards the esoteric( I mean the word in it's sense of highly specialised) and abstract qualities of the medium itself is a reflection of it's contemporary semiotic value. The tradition is evolving. , "form follows function", but the art-form continues to explore the subtle qualities of metal. In this respect the finest works, of all periods, share a great deal in common. I would argue that the symbolic role of the Japanese sword has always been it's most powerful presence, whether on the field of battle, on a katana-kake in a tokanoma in a private residence or on display in an International museum. The complexity of what it represents depends, as Steve rightly points out, to a great extent, on context. This context has always been in flux. To survive, all traditions must remain in flux and evolve to provide meaningful expression... one that is expressive of the times. I believe that is still happening as in the work of the finest swordsmiths at work today...and if I may be so bold as to count myself in their company, I like to believe my own work also speaks to a beauty that is much loved still and provides a vehicle to further develop new beauty within the context of this tradition. This is the crux of what I was getting at in terms of "legitimacy". I think there is a whole new topic to wrangle over in relation to our evaluation of the qualities that these artefacts exhibit and the need for some sort of objectivity in assessing these aesthetics. I fully appreciate Steve's points regarding the ultimate impossibility of true objectivity but I would maintain that this is precisely where the study of aesthetics, [as a tool, not a dogma as some seem to fear, with which we can begin to more effectively analyse and study this art form], provides a framework for a more mature and balanced appreciation. ...and then, of course there's all that nonsense about menuki supposedly having a functional role in improving the grip best regards to all...and wishing you all a most brilliant "year of the tiger" Ford

-

I could try to clarify...but as you won't read past the first paragraph I doubt it'll help All the big words are just shorthand code words for even more paragraphs....count your blessing :D

-

Hi John, yes, got your email...thank you very much. I have to say that to be fair to Mr Leung his article and hypotheses deserve to be assessed more thoroughly, in a separate topic perhaps. Is this something that is reasonable to do here? Having said that It is clear from reading his methodology ( if it can be called that) the examples chosen do seem to be a bit arbitrary. I quote his selection criteria; Only examples from group iii. were chosen and they were in that group because the author was able to identify the type of weapon that likely caused the damage. Mr Leung doesn't qualify his criteria for making these judgements so we must assume it's just a matter of what he thinks combat damage should look like despite not having any proven samples to compare to. Herein lies the problem, they are damaged, that's self evident. What caused the damage is by no means clear at all. As for ascribing specific damage to particular weapons I feel this only serves to further undermine the basic premise as it reveals a willingness on the part of the author to "see what he wants to see". This is just guesswork. Brian, glad you're enjoying the ride... :D . Here's a thought re; all the worlds swords had hand guards observation, almost every culture used shields in combat also....but except in very specific, static positions, the Japanese did not. In any case while I'm certain any guard would offer some protection and was almost certain originally conceived of for that purpose I'm still puzzled as to why we see no evidence of this intended use in terms of battle scars. Great stuff pops up when we all get stuck in and dig around a bit :D and it's certainly woken the forum up after the slumber of christmas regards, Ford

-

John, I don't get the JSSUS but I'd love to see these tsuba. regards, Ford

-

...and yet finding examples of tsuba with convincing battle damage is proving to be a bit frustrating. I've seen helmets, armour and even sword blades all showing battle damage; ie; cuts. but as yet no tsuba It has been suggested that tsuba that had been thus damaged would have been re-cycled. This I seriously doubt. What better evidence of battle field experience could a warrior have...then a battle scarred tsuba? I would suggest they'd be revered as honourable scars of war. Yet they remain elusive....why? And Mark, with all due respect, I don't think your experience in SCA, using rattan mock weapons, can be offered as "evidence". One only has to look to Kendo to see how this sort of "safe" mode of sword play very soon develops into something quite different from a real life or death fight with live blades. The same is true of Western fencing. J, Christoph Amberger's "The Secret History of the Sword" is an excellent reference for anyone wanting to learn more about the realities of combat with cold steel. It makes for very sobering reading. respectfully, Ford

-

Perhaps....but even he admits that much has been lost.

-

Without any desire to open any polemic, i must say that specific point (handguard) can be discussed only by experimented kenjutsu practitionners. I think I probably would have to agree with you Jacques...problem is they all died at least 400 years ago. At least the ones who would be qualified to address the specifics of the original use of the sword as a battlefield weapon.

-

Steve, sorry for the occasionally sarcastic tone of some of my comments. They weren't meant to be deliberately dismissive but Blackadder seems to have influenced me too much I fear I don't labour under a false belief that we capable of true objectivity but I had imagined that as you seemed intent on addressing the subject in philosophical term some degree of detachment from one's own preferences. The problem with your insistence on the apparent primacy of your subjective tastes etc is that we ultimately all end up claiming the same and we reach an impasse where everything is relative. Despite what some schools of thought hold I for one don't find this sort of accommodation to be particularly helpful. Ok, so perhaps you do have a more "in depth" understanding of Edo kinko work than I imagined. Your critique of it is still so unreasoned, based as it is entirely on your own value judgements, that it's hard to take seriously as an honest appraisal of kinko work as opposed to your beloved Momoyama iron. Your critique appears to nothing more than a justification of your own taste. You claim to understand it but don't care for it, fine. Yet your criticisms are so easily countered by so many exceptionally examples of kinko work that I can help thinking you've deliberately chosen only to look at the very worst...while only viewing the finest of Momoyama work. Fair enough, perhaps I do need to far more clear in the meanings I imply by my use of words but it is precisely because I'm attempting to articulate something that is as yet poorly defined that I'm using such evocative and descriptive language...it's what artists do to make meaning ...we sometimes even get quite romantic I sincerely hope so because that is exactly what I'm attempting to to do with my own work. I'll keep searching for my Atlantis then :? My point with regard to "warrior taste" was simply to illustrate that this was only one facet of a much broader and continually evolving aesthetic expression and one that was completely reflective of the times. That you prefer one specific manifestation of this expression is, of course, your right. However, your choice does not render all other forms immediately "less than true tsuba" other than in your own scheme of things. I think you know exactly what was meant by the tsuba not being a "hand guard"...ie; that it's ostensible function was to shield the hand from actual strikes... Semantics aside I think there is a significant difference between something intended to protect from external threat and something that is a "safety feature" intended to prevent injury to oneself. An analogy might be the difference between a car's safety belt and bullet proof windscreens. I can accept that some fitting was desirable to prevent the hand thus injuring itself. This gives us a plausible reason ( in the first instance) for some sort of barrier at the juncture of handle and blade. That this took the form of the tsuba as we recognise it, in all it's manifestations, clearly demonstrates that the specific functional requirement was so easily met and a far more "exciting" range of expressive possibilities were made available to the wearer that this soon overshadowed the initial "raison d etre" . As for wheeling in your "big boys" had you the energy to continue this discussion I doubt anything useful could come of it. Deconstruction of text ( al la Derrida) to the point it has no meaning makes having a conversation a bit of a non starter really. Anyway, I've still enjoyed this conversation. Thanks again for your kind compliments regarding my own endeavours and for your thought provoking responses. best regards, Ford

-

Hi Steve, yes, I reread the last bit and apologies...I didn't fully appreciate what you were saying. I've had a chance to consider the points you've made and think that in some, quite important ways I've not been clear enough in what I am presenting as you seem to have misunderstood my own fundamental position. The validity I refer to has nothing, in my mind, to do with the past in the way you seem to intuit. Rather the contemporary validity is wholly to do with here and now. The impossibility ( and absurdity) of me, or anyone else, trying to make (for example) Kamakura period Owari guards, with all of the connotations they are redolent of, occurred to me many years ago. Your assertion that tsuba begin to degenerate, for want of a better word, once the Edo period begins and continued to the point of nothingness today seems to bear out remarkably well the caricature of one of my hypothetical collector types. Similarly, your dismissal of all of Kin-ko work based on your own taste demonstrates a surprising (in a philosophical discussion) lack of objectivity. Further, my own aesthetic preferences aside, your claim that the aesthetics of Yugen, mono no aware ...et al, are somehow superior to the decadence of Edo kinko work is something you simply cannot possibly prove. You are merely stating a preference of taste. My reference to and dismissal of that " bit of romanticism" was done exactly because I wanted to highlight exactly the sort of preferential bias you've just demonstrated. The words you use to describe Edo kin-ko are themselves very revealing, particularly when contrasted with he way the present the aesthetic you are moved by. To write off the remarkable art of so many truly great artists in metal, based on nothing more than what appears to be a very superficial appreciation of what was actually produced and your own overarching personal taste and value judgement does seem a tad biased...don't you think? I wasn't denying anyone's right to enjoy whichever aesthetic they choose...that's a personal matter. I don't think, however, you can then claim some sort of superiority for your preferences in an objective discussion. btw; the reason I dislike that term; "wabi/sabi" is precisely because it's become such a vague "catch all" phrase that the real depth of the individual aesthetic components becomes muted and lacks refinement. It's also used too freely and often with a very poor appreciation of the real literary evolution of the terms and all the nuances that implies. If I concede that perhaps tsuba did have some practical and functional purpose it never the less remains patently clear that by the Edo period this functional aspect was no longer a significant factor in the further development of the tsuba as art. Basic functional constraints were easily met and the meaning derived from tsuba evolved to meet the needs of a new class of users. One of my opening points, and the rationale for my descriptions of the various interest groups was this; I don't believe I made an "either/or" statement regarding aesthetics vs functionality. I merely posed the idea that in my view aesthetics was the primary driving force in the evolution of the tsuba. You seem also to have run away with my "throw away" reference to unjustified romanticism. What I actually initially said was quite specific; So if they didn't reflect true warrior taste who was buying them...surely they were made for the warrior class? ah! yes...but not the romantic, idealised bushi with his superior taste. Finally, my intention in starting this discussion wasn't to seek approval or validation...I was looking to see how the tradition might successfully evolve as an expression that is true to the spirit of the makers of the past ( I'm not worried about long dead warriors now ), maintains it's integrity and for contemporary work to have some legitimate place in the continuum of art metalwork that is this tradition. This is the question I face each day. I've satisfied myself as to the legitimacy and integrity of what I do...I was merely wanting to hear what others thought... without being hugely invested in any particular response either way. Nothing you've expressed offended me....honestly :D regards, Ford ps. It might be of interest to read the view of Mr Morihiro Ogawa in the new Metropolitan Museum Catalogue, 'Art of the Samurai" in reference to the function of tsuba. "Contrary to some popular assumptions , the tsuba is designed not to protect the back of the hands but to protect the palms by preventing the hands from slipping down the hilt and onto the blade." pp.198

-

Hi Steve, great riposte...and well worth waiting for. I'll now need a moment to reflect on what you've written also. A few quick points I can make at this point though. Firstly, as regards my own work ( and thanks for your kind compliments) I have no personal need to have what I do validated by collectors or anyone else for that matter. At this stage in my life as, firstly a craftsman and latterly an artist my inspiration, drive and aim is reasonably well understood by me. My questioning of the validity of contemporary tsuba had to do with the perception of the tsuba as a meaningful canvas of expression albeit one intimately bound to, and thus reflective of contemporary sword making. The validity I enquire about is whether we, the makers of swords and tsuba today can in fact use these specific canvasses of blade and guard to explore forms of contemporary expression in metal that while being crucially informed by the past is never the less meaningful today. I am completely aware that this introduces an entirely new approach to creating in both traditions....however, I perceive that this is exactly what the finest artist swordsmiths today are doing. Your critique presumably negates the validity of what they are doing also though. ...I'll be back regards, Ford

-

Hi Grey, yes...if modern swords are accepted then is there any question regarding the validity of modern tsuba to address at all? The truth is though, while swords have, however tentatively, managed to retain something of a continuity with the past and presently, contemporary smiths appear to have a very strong sense of what they are about the same cannot be said of tsuba. As an art form, for the most part, it continues merely as a pastiche of the past. The tradition is in grave danger of becoming moribund. Tsuba-shi of the past, those who's art is most highly regarded at least, explored the medium and continually reassessed the inherent possibilities for expression. All within the context of their time, of course. For tsuba to once more be vital and relevant contemporary artistic expressions this tradition of continual growth and questioning must be revived. Simply reworking old and revered models alone only serves to preserve the past and the tradition as a living continuum ceases. My real question, I suppose, ought to be; "what makes a contemporary tsuba a valid modern expression within the broader context of contemporary Japanese swords?"...not as pithy but more accurate. :D respectfully, Ford

-

John, I don't think you can compare the smooth wooden handle of a bokken to that of a wrapped tsuka at all. In addition, I never found my right hand grip to have moved no mater how sweaty my hands became....must be the hairs :D As for balancing a sword....how does that work? In no real way can adding a couple of hundred grams to that area, immediately in front of the grip affect the overall balance of the blade. All it will do is add weight...perhaps this is why those used by "working warriors" were often so light. Some additional weight at the kashira end may have an effect, no doubt, as will cutting grooves but the whole notion of tsuba being used to fine tune the balance of a sword has never sounded plausible to me. Perhaps I can admit that tsuba served a psychological function by merely suggesting some form of protection ( wouldn't that be an aesthetic consideration again though ) but we've yet to see a single example with evidence of scarring that would indicate that was ever needed. The sword never was the main battlefield weapon anyway...and when not actually fighting, warriors...even Japanese ones, tended to be very image conscious so the use of tsuba as a "statement" would seem quite natural. Status was a major concern of warriors even in the midst of the bloodiest battles...for many it was the only reason to be there. I haven't been considering these effete swords really but to be fair they were clearly fit for their intended purpose...which was to be flashy and effete at court. But if you consider just tsuba, you'll be hard pressed to find many examples that are completely useless because however we define their function a simple, quite thin plate ( even lacquered leather apparently) will do the job. As to epistemological concerns...my post was intended precisely to challenge conceptions and to ask why we believe what we do with regard to tsuba. Job's a good'un :D and I share your view...if I'm wrong I'm ok with that...I'm still figuring stuff out, a work in progress. regards, Ford Ford

-

Jean, funny you should mention Gaston Bachelard...I've been working through his "Poetics of Space" over the last few months...in English translation ...naturellement

-

Well...I'm quite pleased my ramble has piqued some interest and I'm very interested to see how this discussion my evolve. My intention with this (deliberately provocative :D ) post was to open up some sort of a dialogue, my own work and relationship to the tradition is of course an inescapable aspect for me but I'm very flattered by the extremely generous compliments many of you have paid me.... Steve, I hadn't intended my post to be a definitive philosophical manifesto, merely, a "jumping off" point and possibly a bit of self justification... having said that I'm quite looking forward to your critique so that I might be able to better analyse the formulation and credibility of my propositions. Not having had any sort of academic philosophical training I'll keep spell check on high alert To address your first point, I assume you mean this bit; The romanticism, in my view, consists of a neat and tidy projection by modern collectors ( I suspect it wasn't uncommon in the Edo period either) of what constituted proper "warrior taste". While it may well be true that a certain taste was officially approved of and maybe even encouraged, this narrow definition by no means encompasses the entirety of Kamakura and Momoyama period aesthetic expression. My own feeling is that much of the purist view has been "reverse engineered"...perhaps as a way of trying to bolster a fading image of this warrior class much in the same way the notions of warrior chivalry ( in Japan as well as Europe ) were ideals that could only be articulated after the fact. I wasn't specifically referring the the apparent functionality of guards as being "romantic" but while I'm about it I might as well address that aspect too. I don't believe the primary function of tsuba was in any way related to issues of physical use. We've generally agreed, I think..., that the tsuba was not intended to act as a guard to protect the hand. Instead we are now told ( by them....!?) that the function was to prevent the hand from slipping onto the blade. This seems to be to be an utterly contrived justification. Given the kind of wraps we see on battle swords, ie; lacquered same and doe-skin ( this often also lacquered) it seems clear to me there was little concern that the tsuka didn't provide sufficient grip to allow a sword to be wielded effectively. Surely you wouldn't make it all smooth with urushi if the whole wrap had a tendency to be slippery? We also note a passing fancy for long swords that were mounted without tsuba. If for a moment we do allow for the notion the tsuba was there to stop the hand sliding forward when performing a thrust why was the guard so big? A disc extending no more than 10mm from the seppa-dai would suffice. I believe that attempts to explain the use of tsuba in functional/mechanical terms are spurious and that it's true "function" was always, and primarily, aesthetic. As such, the tsuba "functioned" in all periods, to display the status, cultural refinement and personal taste of the wearer. It also allowed for political loyalties and philosophical concerns to be signalled. It was in these contexts, that the tsuba as an art form expressive of the time and group who used them, developed. It is out of this analysis that I begin my own questioning as to what constitutes a valid expression in this art form today. ...now I need another cuppa. regards, Ford

-

I trust everyone is gently regain some sense of normality ( if Nihontophiles can ever really approach that state ) after the exertions of the festive season and I hope the new year, the tiger' proves to be brilliant for all of us. We engaged in some vigorous rearranging ( along feng shui principles ) on my own forum and while moving the furniture around I had a moment to reread some of my older posts. What follows is a sort of summation I came to after a brief discussion we'd had regarding the legitimacy of contemporary, particularly non-Japanese tsuba and I offer it here in the hope that it may stimulate further discussion or even perhaps a reappraisal of sorts. I had wanted to post this just before the DTI last year, when Mike Yamasaki initiated a discussion along similar lines...I had too much on my plate at the time, I'm up for a good discussion now though. The first time I actually saw real tsuba they were behind glass in a museum in Cape Town, all pierced and carved steel. I was lucky, they were all quite decent examples. I've seen them since and it wasn't just a case of not having seen anything else to compare them to, I was already an apprentice goldsmith so I was getting design and technique drilled into me all the time. As intriguing objects I found them fascinating. The fact that they weren't mass produced industrial products, castings, made them seem all the more precious. But the thing that really resonated with me was the term "chiselled steel" The very idea of being able to work steel in such a direct way was to me completely magical. I had no idea how to go about it but as I pored over every picture of tsuba I could find, and this was in the dark days before the internet spread the light, I became more and more captivated by this, apparently lost, craft tradition. Like most of you, I was utterly amazed at this miniature world of metalwork, still am.The delicacy, skill and sensitivity not to mention the novelty was like a drug. At this stage it was the desire to "re-discover" these amazing techniques and methods that drew me on. The idea of actually making something original never entered my head. For me, then, it was all about the technique. I was lucky, again :pray: , that as I was developing as a goldsmith my skills allowed me to make a few passable versions of tsuba. Piercing work and filing are basic skills of my trade so there seemed no reason that those sorts of tsuba couldn't be copied quite easily...but then I wanted to go further. By the time I got to London I was ready to start getting into the metal, actually carving steel. I made a start by copying an older guard. The result was reasonably satisfying but it was suggested by a number of people, at the time, that there was no point copying older designs and that I should concentrate on original ideas. This is where things start to get sticky. It is generally accepted, today, that artwork should be, by definition, original. The problem with this particular format; ie, tsuba, is that it is not something we really have any instinctive awareness of. It doesn't really come out of the world that has shaped us. It is actually quite an alien object. I took the, well meaning, advice and begun to create my own designs within the restraints of the "little metal disc with slot in the middle". In terms of design I think I learnt a lot at that time and most of the work I produced still pleases me. Different people have very different opinions, as we should expect, tsuba collectors in particular, seem to be the most difficult to please. In retrospect I think that my study would have been more effective at the time had I concentrated on good, classic examples but it is difficult to know for sure which approach would have served me best. Had I made decent copies I would have possibly been able to sell them more readily and thus been able to devote more time to my first love. Instead, I ended up specialising in the restoration of the very sorts of things I wanted to make. Something to bear in mind if you're as mad as me. From my experience of collectors I would suggest it might be helpful to consider for a moment what actually appeals to them ( that's you lot :D ...forgive my oversimplifications and if I missed your own quirky approach ), as a way of trying clarify what tsuba are to different people. I think that generally speaking there are 3 main aspects we can identify and each view holds a part of the tsuba's identity. I am going to ignore the fact that most collectors hold a combination of these views because I want to focus precisely on these specific traits. One type of collector is very aware of the tsuba as being a Samurai artefact. This is often not even conscious but the "purist" will insist on the functional criteria being of most importance, followed by it's aesthetic expression being that of the warrior class. This is generally the "wabi/sabi" ( how I dislike that term :snooty: ) feeling of the Kamakura and Momoyama periods ( roughly 1200 ~1600 ). An essential quality of these guards is, of course, their age. No getting away from it....old, iron ( mostly ) and once used by a warrior. It is obvious that these cannot be made today. Incidentally, many of these purist types are quite dismissive of even the fairly sombre iron guards that were produced in the Edo period. The claim is that they don’t reflect “true” warrior ideals and taste. The flaw in this little bit of romanticism is too obvious to elaborate on, so I won’t….unless you really want me to. :sneaky: There is a sub-group of this first type of collector that I should also draw attention to. This is the person who believes that the age of the piece is the most important thing in it’s appreciation. This rather extreme view, in terms of art that is, states that old is good, very old is even better. Here we leave aside aesthetic concerns regarding tsuba and are in the realm of corrosion appreciation. Gnarled and severely corroded ancient metal artefacts, regardless of their possible attractions, are simply not in the same category as consciously produced art works. So we can safely discount this peculiar taste. The second collector we might encounter has somewhat broader tastes. He ( there are some ladies but generally we're talking about men here ) appreciates a type of work called "kin-ko". This is work in non-ferrous metals and involves inlay work, carving and a fairly colourful palette. Although some schools did use iron grounds they are still considered as being kinko work ( Soten, Hamano, Tanaka etc ). The Kinko workers of the Edo period created a self contained art world that explores an incredible range of aesthetics and techniques. Some of the finest works of art in metal belong to this genre. Here too though, history adds its inimitable touch. A part of the allure of this work is also it's age, and the world that gave birth to it. The social conditions, the people who loved these objects. Warrior class and merchant taste. The very refined, or the ornate, taste of the upper classes of the governing warrior class. It should also be added that although technically not kinko the many schools of the Edo period that worked either only in iron ( Akasaka, Bushu, Choshu etc ) are often also well appreciated by this category of collector for their outstanding design and craftsmanship. This brings us to the third aspect... This is the appreciation of the pure technique and artistry in metal that these curious little objects display. Here, the age of a piece is not a real consideration. The work is appreciated and enjoyed purely as metal art. This view does inform most collectors to some extent but is extremely rare, if not non-existent, on it’s own within the so called “Japanese sword world”. In the greater “art world” however, there seems to be a growing awareness ( I truly hope… :pray: ) of fine metalwork’s purely artistic potential, or at least, aspirations. By now it will be painfully obvious that any attempt to recreate any of the various types of tsuba, that collectors are drawn to, is bound to fail, if only because of the question of age. The many other aspects not withstanding. I think though, that my description of the various views of the subject actually offers a way forward. It is obvious that certain features are common to all views, except the lovers of gnarly corrosion products…but they have their own needs. :crybaby: This is the expression of meaningful aesthetics, and fine craftsmanship. The obvious, "purely mechanical” functional aspects of tsuba are in fact quite easily addressed so I’ll keep to the topic of artistic expression. I maintain that an ongoing study and appreciation of these wonderful examples from the past may allow an artist in metal to develop their own, genuine, aesthetic response to the techniques, materials and constraints to this format; the tsuba. I don’t believe much is to be gained by attempting to rework traditional subjects or themes. But do suggest that an awareness of the context of the guard is essential. Using “traditional” designs will inevitably draw comparisons with the original works, and sadly, the copies will inevitably appear awkward and contrived. This is not the same though, as copying an existing piece to better understand the subtleties of design and technique. What I’m warning against is the attempt to create “in the Japanese style” . This will only result in a superficial and unlovely mutation that will ultimately end up an orphan, belonging nowhere. For myself, I have made my journey through this tradition, in a way that tsuba-shi of the past never did, nor could have done. I have had the privilege of surveying the entirety of the tradition and tried to breathe it all in. It is from this stance that I now attempt to find a language of my own, fully informed by this past, and one that is still part of that continuum. There is no call for iron guards meant for Bushi ( warriors ) of the 1500’s, but there is an appreciation of the beauty of the jewel-like, kinko work of the Edo period, and perhaps even some contemporary appreciation for that old tea ceremony inspired taste…and fine workmanship will always be loved. Sensitive aesthetic expression is a valued commodity in the world of art collectors. So... Yes, I think we can still make tsuba that are worthy of that name and that continue to explore what they are…or can be. These small sculptures in metal have a long and fascinating history, one that has never stood still. So why should they be relegated to museum cabinets now? I believe there is life in this beast yet... and we can draw on the richest tradition of art metalwork the world has ever seen.:biggrin: We could go on to discuss the need for a tsuba to have a nakago ana in the same way that netsuke “need” to have himotoshi to qualify, but that is for another day I think. I look forward to hearing your views. regards, Ford

-

Hi Simon, you could try contacting Pierre Naduea over at soulsmithing; here's a link. He's doing an apprenticeship in Japan and may be able to find the sorts of "struggling artisans" you're looking for. You will get what you pay for though Alternatively if you're looking for a top notch job and are prepared to pay for it I can put you in touch with a colleague of my own teacher, a Mr Hiroi. He recently completed some koshirae for the Ise Shrine. Peter Quin, a South African member here, has had a number of koshirae put together under his direction and was very happy with the results. Perhaps Peter could advise you as to the costs. regards, Ford

-

Mark. I believe the copper plate is a later addition. The person who applied it obviously didn't want to destroy the original patina of the iron by cutting a mei directly into the steel so they opted for this approach. The area immediately surrounding the tanzaku can be seen to be "disturbed" and is no longer perfectly flat. Still, it's a perfectly appealing tsuba as it is regards, Ford

-

John I would have to agree with Clive, the kenjo tsuba you've shown sports a seal not a kao. Incidentally, kao/kakihan (monograms) are typically derived from a single kanji of the artists mei. The abstraction follows semi-formal conventions. My own teacher told me there are 3 basic formats in terms of overall shape. The type bounded by 2 horizontal lines, like the one on Clive's tsuba and the Yasuchika one of Barry's being quite different styles. Lovely kuchi/kashira by the way, Barry. I'd certainly have no qualms about accepting them as easily convincing enough to be my the master. The chidori ishime ground, the colour of the shinchu and the soft ( very distinctive) modelling of the brush are all exactly as one would expect...in my opinion. regards, Ford

-

aaargh! earthquake!!!

-

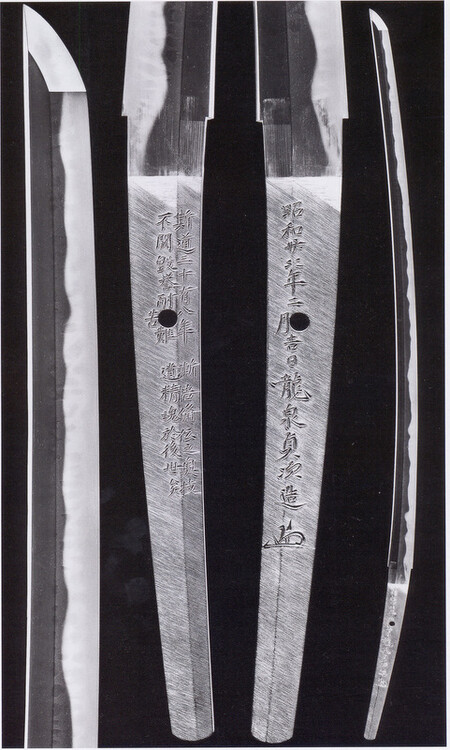

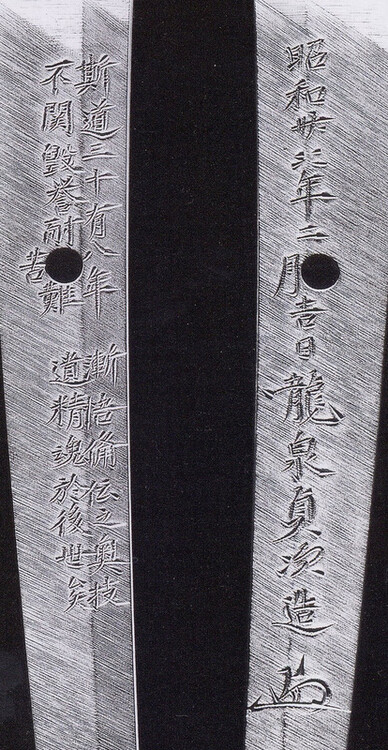

Festive Yule tide greetings to all from sunny Cape Town! ...I've been a very good boy...look what Santa left under my tree

-