-

Posts

3,091 -

Joined

-

Days Won

78

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Ford Hallam

-

Hi Steve, yes, those tiny grains to the right and above the mei are what I'm referring to. I'd also suggest the unusual surface around the turtle piercing is possibly due to the plaster of the mould braking away and creating, in effect, a scab on the cast object. This braking down of the mould around the sukashi would also explain the need to hammer the openings closed and to reshape them somewhat. The hammer marks are quite clear. As for the way the original works were finished I have to confess I can't say for sure what was done but I can rule out certain processes as their effects are quite distinct. As I see this finish now (my views are very much a "work in progress" as I develop my own approaches and see more) I recognise a carefully hammered ground that has also been softened by use of controlled oxidising. By this I mean a process of heating the steel to form a iron oxide, scale layer. This is then removed by means of a suitable acid that only really affects the scale and leaves the underlying steel untouched. This procedure can be repeated any number of times. This results in a particular, natural sort of skin that is called "hatasu" in some studios I've studied in. Another, very significant feature of this sort of controlled oxidisation is that differing steel compositions (the carbon content being a main factor) are consumed at different rates. Contrary to general perception, higher carbon content steel is more readily corroded than the low carbon steel. This fact has a serious implication with regard to the formation and interpretation of tekkotsu also. The smoothed and rounded appearance of certain guards (Hoan, Yamakichibei et al) could, in my opinion, be quite reasonably be explained as being the result of careful filing, polishing with small stones and burnishing. My feeling is that this sort of finish was something that these makers developed gradually and is the result of a number of steps that are all very much a matter of the maker gently working the surface to create the sort of expressive "skin" they felt appropriate. Incidentally, this is also why I am doubtful of various claims as to the apparent qualities of steel merely from visual observations. Hi Colin, I went into some detail elsewhere on the forum about the procedures for making cast steel copies. You'll find the entertaining "debate" here. The implication I make is that if it's cast steel its modern, ie; probably no older than 50 years but more likely 5 years to be blunt. The addition of the sekigane( in different metals, albeit with a very fresh copper patina) and the lining to the kozuka hitsu are merely evidence of the increasing sophistication of fakers. If I can do it then so can they...although, obviously you'd never know if I did it regards, ford

-

Gentlemen, I have to agree with much of what has been suggested. While it is quite difficult to judge confidently from photos I does look like fire damage to me too. Those "flakes" do look more like fire scale than lacquer to me and the overall texture seems to fit with the effects of severe oxidisation. I think George has described the likely history of this piece quite convincingly. regards, ford

-

Colin, In my opinion I think there is sufficient visual evidence in the close up images to draw the conclusion this is a cast copy. Sorry for being the "bad cop" but the evidence is there and it's quite clear. The first clue is to be seen alongside the mei. Those tiny grains on the steel surface are incontrovertible proof this steel was cast in to a plaster mould. These tiny bubbles are caused by minute air pockets in the surface of the plaster that forms the mould. It's a common feature of cast metal. There is no other metalworking process that results in anything similar. While we're about it I'd like to publicly state, in writing , that I don't believe in a process called "yaki-shitate" at all. I don't know who came up with this fanciful notion but it strikes me a extremely improbable and more the result of the fanciful imagining of an armchair "expert" who'd never worked hot steel. I may be wrong, it has happened before :? ....but steel at temperatures close to melting (in fact the surface is suppose to melt in this theoretical process) absolutely does not act like wax and result in a soft and gentle surface...quite the opposite in fact. Ask any swordsmith. Regards, Ford P.S. Come to think of it, this "yaki-shitate" idea may have come to the attention of western collectors via "Tsuba - An aesthetic Study". It may be that the term was intended merely to describe a visual feature (like karasugane implies shakudo looks like a crow or chirimen-ji merely looks like crepe silk) as the actual techniques followed to produce this look remain unknown...to most This is a close up of the surface of a genuine Nobuie. This is clearly not a surface that has been melted in any way. I'd also just like to point out that Nobuie didn't use kebori in creating his designs. No metal was cut away which is what kiri means, "to cut". These little "steps" you can see very clearly in the lines here are indicative of a punching technique where the metal is merely displaced. This technique is called giri-bori. I raised this point previously,here. and go into a bit more detail. You can examine some more examples here.

-

must have been while you were at the bar

-

Just to take one of my trains of thought a little further I want to introduce another example by Funada Ikkin. I "borrowed" this image from a website about 5 years ago but the site is no longer on-line and I can't remember who's site it was so I don't know who to ask for permission to use the image. If it's yours I hope you don't mind but if it is a problem please let me know. Unlike the first Ikkin example I posted this one is even more minimal in that it features no inlay work at all. For me this piece is a continuation of the initial aesthetic impulse we first encounter ( in the examples I posted) in the work of Nobuie. This is a plate of metal, in this case shakudo, that appears to simply have been forged down into a suitable plate and had the rim hammered up (this is called upsetting in forging terms) to provide a sort of frame to it. The aesthetic that the workmanship expresses is direct and seemingly uncontrived. It's a sort of naturalism in metal. The actual decoration is also very direct, just like a bit of brush and ink work. The engraving/carving technique is immediate and allows for no alteration...very Zen like, and the texture left within the cuts by the chisels further speaks of an honesty of approach and perhaps even spontaneity...relative to a very refined and overworked bit of carving say, like the Ishiguro. There is evidence of the process of engraving and modelling the hawk on the Jingo piece also but there it tells a different story. There it adds to a feeling that the work is almost naive. Of course, it's only appears that way, it's actually quite difficult to express that sort of looseness and "freshness" in carved metal but it's not quite as spontaneous as the chiselled decoration of Funada Ikkin. For me, Funada Ikkin is one of the artists in this tradition who best exemplifies an approach that utilises the actual tool marks and processes themselves to give his expression vitality. The "drawing/painting itself is very elegantly allowed to drape around the edge, again, almost incidentally..as though it "just happened". It doesn't betray any sense of having been over thought. Intriguingly though, if you really examine the way the chiselling begins, the way it "emerges" from near the rim and how the lines move in and out as they flow you may begin to see a subtle interaction, this is not an accident and for me at least reflects the complete immersion and sensitivity of the maker. There is not one superfluous mark there and each one has been created as and where it is with sublime care...and there are 3 more side like this! the reverse and the 2 sides of the pair to this tsuba, and each one unique. This tsuba is actually one of a daisho pair and I think they're masterpieces and embody for me much of the essential spirit of the tradition. Certainly in my top 10

-

Keith, I understand what you're getting at and in most respects I tend to agree with the notion of this whole "thing" being continually in flux. What this then leads me to is a sort of intuition about the "character" of the ongoing Japanese creative response to all these various influences. It seems to me that there is, underneath all the external appearances of the actual works of art, a "personality" that deals with these matters in a coherent way. Does that makes any sense?...or do I need my medication? As an attempt to put my finger on one such "personality" trait I offer the tendency to appreciate delicacy in objects and a real need ( so it seems) to really refine technique almost purely for it's own sake. This seems to me to hint at a desire to view art and the world it reflects in almost abstract terms. Take the Nobuie tsuba, for example. Which other culture would (could have or even wanted to) have developed that particular aesthetic? Consider for a moment what that tsuba actually reveals in terms of steel making technology and the refinement of processing the material that then allows for the soft, almost natural, modelling of the surface and the development of very sophisticated process to create the patina and colour. This is quite a commitment to a form of expression that is remarkably understated and apparently uncontrived. Yet this intimate and subtle expression is often at the very heart of things "quintessentially Japanese" ...it's almost the bedrock, if you'll pardon the strained analogy :? We can see this exact expression in the Jingo tsuba too. There's a delicate difference in terms of the actual modelling and form as we'd expect from two different artists but both working very much from the same aesthetic impulse. Shimizu Jingo evidently has another aspect to his character though and he reveals this in his decision to contrast the "yugen" of the plate with something quite different. His cartoon-like designs, the hawk being one of his classics, speaks of humour and light-heartedness. The gentle way he treats his creatures is genuinely charming and utterly unconcerned with trying to hard to impress. In this he is the polar opposite of an artist like Ishiguro Masayashi. Just compare the Ishiguro birds with those of Shimizu Jingo, it would be hard to find a greater extreme in terms of approach. Yet both are instantly recognisable to us as being Japanese. I would go so far as to tentatively suggest that the Jingo work is more authentically Japanese though, and if you can entertain that thought then you may also wonder if Goto work is really all that representative of "true" Japanese aesthetic... or was it merely the officially sanctioned taste of the shogunate and more reflective of neauvo riche aspirations and as such looking back to Chinese/Confucian notions of refined taste.

-

Do you like these fuchi koshirae?

Ford Hallam replied to jason_mazzy's topic in Auctions and Online Sales or Sellers

My apologies, Fred. I thought you were commenting on the f/k that started the thread ...and I won't say anything disparaging about Jean's pieces as I still plan to make a dent in his wine cellar when next I'm in Paris. -

Do you like these fuchi koshirae?

Ford Hallam replied to jason_mazzy's topic in Auctions and Online Sales or Sellers

I envy your absolute certainty ...would you care to elaborate what you mean by "nice"? in anticipation, ford -

Do you like these fuchi koshirae?

Ford Hallam replied to jason_mazzy's topic in Auctions and Online Sales or Sellers

forgive me, Martin but I must be pedantic and disagree. The set is indeed brass, whether patinated or not is not relevant in this case, the Japanese terms for brass is "shinchu" and typically it comprises copper and no more then 15% zinc. There is frequently a trace of lead present also. Sentoku is an altogether different alloy that lies between brass and bronze in terms of composition and is unsuitable for forging out into workable sheet such as is needed to make fuchi/kashira. Judgements of quality will naturally always be subjective so I will only offer my opinion to say that while I don't think these are terrible I would hesitate to call them good. They are honest pieces of production work that I'd rank as being only barely a step above "completely dismiss-able". The design is "pretty" but obviously simply taken from a design book. The workmanship is tidy enough but lacks any sort of feeling at all and borders on rudimentary/crude. Just my view on these pieces... regards, ford -

Fellas, I'm definitely not one for bailing out....if there's a good conversation going I'm up for it. I was just beginning to wonder if the whole topic was ultimately not that interesting to most of our members. I'd hate anyone to feel that they needed to hold back for whatever reason. There are no absolutely right or wrong suggestions, comments or observations. I genuinely believe the process of groping our way as a group will be fruitful. I just don't want to be "lecturing" or reciting the "gospel according to me" In science, even the theories and experiments that don't work out as expected often yield valuable new insights. I think we can do the same here. So, have a good look at any of the examples that appeals to you, or catches your eye for whatever reason, consider it in the light of the terms I've offered and see what occurs to you. I'll happily engage with anyone if they want someone to talk to or bounce ideas off. best, ford

-

...ah well...it was worth a shot. At least no-one can say we never tried. (apologies to Mick Jagger and Angie) I'll just put my thoughts in my book instead regards, ford

-

Hi Keith, you get my point exactly so the next step, in my conception of things , is to begin to try and discern how the evolving Japanese character, sensibilities and philosophies makes their appearance in their own art forms as distinct from foreign borrowings, what specifically do the Japanese bring to their art that we don't generally recognise as readily in their neighbours art? Most of the clues, I'd posit, are to be found in the very terms that we can use when talking about Japanese aesthetics. Ok, so maybe I get the prize for stating the blindingly obvious but by examining these terms and the origin of these particular sensitivities we may begin to get a better picture of the Japanese aesthetic spirit.

-

Hello George, Keith, et al... I'm really appreciating the way this exploration is evolving. I think the intuition to get "back to basics" so to speak, is a sound one. To add a further consideration I'd point out that what we may be referring to as "original Japanese aesthetic" itself came from the Asian mainland. Most notably China and Korea. The well documented "Ring pommel swords" are a good case in point. They are found in Korean archaeological sites as well as China and Japan. It's generally accepted that Japanese metalworking traditions developed from imported technology. Naturally enough this was accompanied with imported styles and aesthetics. This imported tradition soon begins to evolve in ways quite different to the ways the original sources do. This is where we begin to see the manifestation and birth of native Japanese impulses and tastes. At this stage it may be worth pointing out that we're ignoring the original inhabitants of the islands, the Ainu. We're not discussing Ainu aesthetics but it I wonder what, if any, influence they may have had. I feel that we may find some clues to this elusive "Japaneseness" by considering the impact of early animist beliefs, notably that which is now known as Shinto. The later assimilation of Buddhism brings with it another layer of aesthetic expression that also feeds into this developing "Japanese aesthetic". I get the impression that it's in the way these various spiritual/philosophical ideas are expressed in art that we can discern something uniquely Japanese.

-

sorry Jean...the missing verb was correctly supplied by Brian One of the chaps on my forum just posted this tsuba. I thought the bow made an interesting match.

-

Thanks John. I'll change my label to reflect that.

-

I'm with Curran....later Umetada seems more appropriate to me too.

-

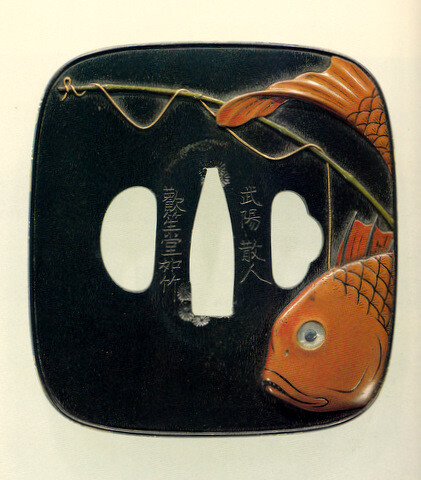

Keith, great start ...and I really wouldn't want anyone to feel worried about making similar sorts of analysis'. I don't think there can be any absolute, hard and fast, right or wrong answers. This is supposed to be an exploration....and a bit of fun. So I won't refer to your impressions but will merely offer some more background information on that example and you can see if there's anything there that confirms your ideas or suggests further connections to you. The maker of the tsuba that caught your attention, Murakami Jochiku, is really one of the true iconoclasts of the tradition. By which I mean he really did do things a little different. :D His use of mother of pearl, the eye of the fish in this instance, was quite an innovation at the time and is a recurring trait of his. That background texture ( it's called chirimen, a type of silk crepe ) is also very strongly associated with his work. One story suggests that he couldn't afford the services of a professional nanako specialist so was forced to develop his own treatments...necessity being the mother of invention Another consideration is the subject matter, the big Tai fish is associated with one the 7 Gods of fortune, Ebisu. Ebisu was often paired with Daitoku (who's emblem was a mallet), these two were favourites deities of the merchant class. I really liked your interpretation of the "big fish versus the small rod" as being suggestive of "the one that got away"...a story I heard every day from my brother, growing up. :lol: I was also struck by your comment regarding Art Nouveau. You may be interested to read what I wrote on my blog some time ago on this artist, in that regard. Here's a link to the entry.

-

Hello all...I'll try to keep on top of responses and take them one at a time. Barry, glad to hear you're enjoying the thread . By all means make a pdf available, there are large images available in my Picasa gallery I linked to also. Sorry about leaving Natsuo out. I did consider him but he was quite versatile in a number of different styles that choosing a representative work is difficult. He also did some some very sophisticated pieces that are quite "intellectual" in the way he was clearly attempting to express various aesthetic sensibilities derived from literary sources. In a way he makes a very complex study on his own. I'm hoping that as we proceed I might be able to introduce his particular modes of expression. I'll reveal a recent, original design, tsuba of my own shortly. It contains a number of references to the past so I'll be interested to see how much is discerned by our illustrious company :D after this particular exercise. John L, thanks for your input. I was hoping you'd elaborate on that area, it being a speciality of yours. Like you I felt unconvinced of a Momoyama period dating for the Namban/VOC tsuba. I pushed the date to early Edo but didn't have any more to really go on other than instinct and some vague notions. Your explanation is exactly what I needed. Should I further adjust the date, do you think?...perhaps 1650 ish? With regards to the Hizen tsuba that was just a blind spot on my part. I don't know what I was thinking when I did that and I hesitate to disagree with Graham on this as he's much taller than me. I'll correct that date. Thank you for your kind appreciation on the selection of examples I've chosen. I think they have much to reveal. Mark you may be right about identifying Iki/Seijaku there...I do try to keep stylish and exude a certain calm ...at least in my work George, If I may, I like to suggest we try to keep our focus on the examples I've posted as this may help us develop a clearer overview before we attempt to see various aesthetic traits in other more generic examples. I've tried to provide a reasonable time-line of aesthetic evolution, if we can call it that, so I'm hesitant to introduce further examples that may cloud the overall impression I'm hoping to create. Keith, I feel as you do, we may gain a more sophisticated appreciation of what influences are evident in those pieces which apparently appear to be of foreign influence ( be it Chinese, Spanish, Dutch...maybe it was all down to Will Adams ) by first discerning what was there before...ie; What did indigenous Japanese tsuba look like at the time without outside influence? This is why I felt it may be useful to go back to the start, so to speak. George, my comments to Keith hopefully explain my approach in investigating this huge subject. I believe we'll eventually be able to regard these Namban works in a broader context and perhaps see them as being not quite so abruptly foreign. regards to all and I trust this topic is stimulating at least some revaluation of preconceptions :D ford

-

Hi Steve, good to hear from you. I was hoping you'd join in...despite how busy you evidently are you probably won't be able to stop yourself 'cos we'll be having so much fun I considered "mono no aware"...or simply "Aware"...that visceral feeling (almost of shock) that great art elicits but decided that while an object can cause that feeling in us I wasn't sure it was something an artist could deliberately attain....not sure Your suggestion to "find" the various expressions in the examples I've show is precisely what I was hoping for. You noted that I included a few terms that are very close but are in fact subtly different (wabi/koko) I think this may help to introduce the real nuance these terms express. Absolutely, as someone working in this medium this is for me the most important aspect. The subject matter, for me, is not that relevant at all. I choose my subjects because they allow me to explore essentially abstract qualities...but that's just me :D However, the appreciation of these material qualities is often more important to many Japanese connoisseurs also. well...I think we're off to a good start regards, ford

-

There you go, George. You're seeing the tsuba through a filter of Japanese aesthetics :D . We don't know what the artists intended but we do know these various sensibilities inform the overall Artistic tradition. If that's what you perceive then you've applied this bit of insight in appreciating this particular work. In the case of your tsuba the theme; ie; the stone stupa and scattered pebbles, expresses a particular pair of aesthetic concerns, Yugen/Mujo. What we can do further is asses how the actual work is carried out. Does the style of workmanship tell us anything? Does the technical treatment provide any further clues as to the sensibilities of the maker? Nobuie, Hirata Hikozo, Goto....all very different expressions in terms of workmanship. What do these aspects tell us about the aesthetic leanings of the artists? Anyone else out there?...or are you all going to leave it to George and I to figure out on our own .

-

Hi George, your observations are spot on with regard to the influences you've noted, although I'm not sure Myoju is too reliant on the Chinese for his particular design sense. We'll no doubt get into that as we proceed. I'd also suggest that we try to identify those aspects that are generally considered to be "quintessentially Japanese". Things like; wabi, rustic, "as is", celebration of natural irregularity and accidental/incidental evidence of process sabi, originally meaning "chill", "lean" or "withered" now more "gentle patina of age" etc. yugen; subtle profundity mujō; impermanence iki; stylish elegance karei; gorgeousness shibui; astringency miyabi; courtly refinement and elegance Fukinsei; asymmetry, irregularity Kanso; "less is more", restraint Koko; weathered as distinct from sabi Shizen; unpretentious, the original nature of things Datsuzoku; unconventional, avant garde, original Seijaku; calming tranquillity. Asobi; playfulness By looking more closely at these aspects we may begin to gain a clearer conception of what Japanese aesthetics really look like and what qualities were appreciated then, and now.

-

-

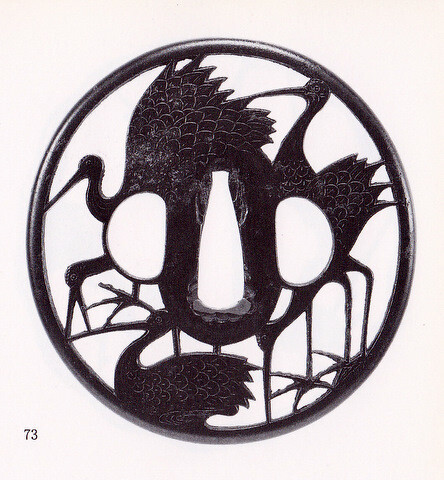

Part V... Omori school. 1730~1798 Mitsuoki Otsuki. 1766~1834. Ishiguro Masayoshi. 1775~1862 Funada Ikkin. 1812~1863. Araki Tomei. 1817~1870.

-

part IV...I may need some correction on the following 2 dates...John L, any suggestions please. Namban. second half of the seventeenth century Circa 1675... ish! Tsuchiya Yasuchika. 1670~1744. Murakami Jochiku. circa 1750. Akasaka. Mid Edo period. Circa 1700~1750 Hizen. circa 1750