-

Posts

483 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

2

Iaido dude last won the day on December 4 2024

Iaido dude had the most liked content!

Contact Methods

-

Website URL

hyotanantiquesandcollectibles.com

Profile Information

-

Gender

Male

-

Location:

Gainesville, Florida

-

Interests

Sukashi tsuba (up to early Edo), iaido, kyudo, Japanese zen paintings (pre-17th century)

Profile Fields

-

Name

Steve H

Recent Profile Visitors

3,609 profile views

Iaido dude's Achievements

-

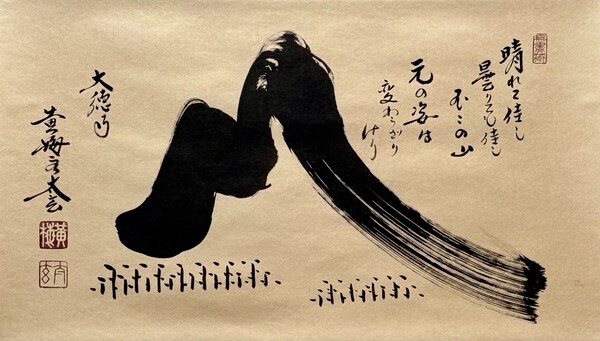

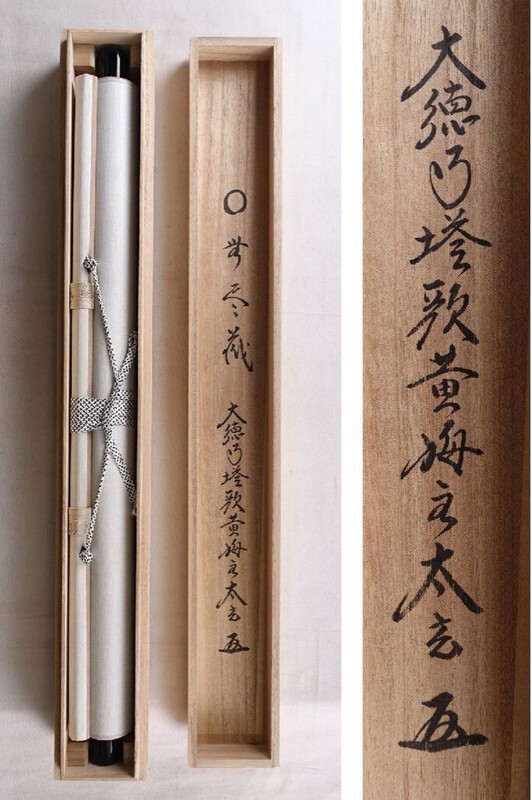

The third work I have by Kobayashi Taigen is his version of Yamaoka Tesshu's Mount Fuji, which is his account of his own enlightenment experience. Comparing the images in all three, his brush style becomes quite evident. Here his calligraphy style is looser, perhaps gently influenced by Yamaoka's highly idiosyncratic cursive script. Fuji is written here as "not two," a play on words that is intended to indicate the absence of dichotomy that characterizes the state of enlightenment. The Tao/Universal Principle/Regenerative Tissue from which all phenomena of the world arise and return--is eternal and unchanging. Perfect when clear, Perfect when cloudy, Mount Fuji's, Original form, Never changes

-

Kobayashi Taigen was born 1938 in Shenyang, China and raised in a Buddhist monastery from the time he was six years old. In 1975 he became successor of abbot Miyanishi Genshō at Ōbai-in, a sub-temple of Daitoku-ji, Kyōto. He is a prolific calligrapher and maker of tea bowels and bamboo tea scoops for traditional tea ceremony (chanoyu). This Enso painting has the inscription "Inexhaustible (無尽蔵)," which is part of a wisdom poem attributed to the Sixth Patriarch of Ch'an Buddhism Hui-Neng. Zen practice seeks to free the mind from dualistic, discriminating thinking. However, "not one thing" or "nothingness" is not equated with emptiness. Rather, with a mind emancipated from delusion, the possibilities become truly inexhaustible. Mu ichimotsu chu Mujinzo 無一物中無尽蔵 In nothingness, there is inexhaustible abundance What an apt inscription to accompany an Enso--the circle that is at once empty and full. Kobayashi's work is characteristically and consistently elegant, as in his "Ichi," with a beautiful flying white brush technique.

-

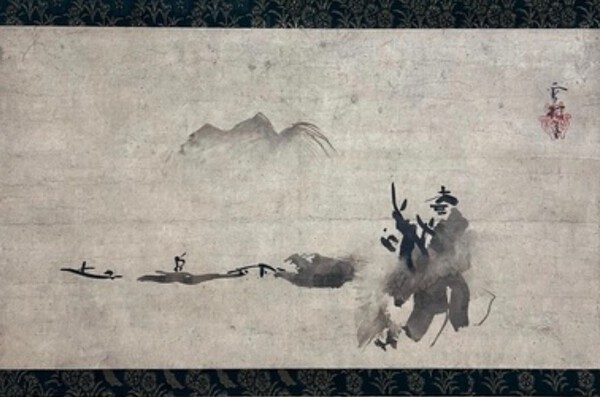

Sesson Shūkei (雪村周継 1504-1589) was a Muromachi Period Soto Zen monk and self-taught artist who is considered the most distinguished and individualistic talent among the numerous painters who worked in the style of Sesshū, the 15th-century artist considered the greatest of the Japanese suiboku-ga (“water-ink”) painters. The two are referred to as "Sesshū of the west, Sesson of the east". He studied the paintings of Shūbun (a suiboku-ga artist active in the first half of the 15th century) and later, from 1533, those of Sesshū and called himself Sesson Shūkei in tribute to the two masters. He worked in a dramatic style that generally accentuated idiosyncrasy, humor, and exaggeration in his approach to subjects, whether figural or landscape. This sansuiga (ink landscape painting) work is an excellent example of his almost calligraphic brushwork style. The boatmen are depicted in a sunset scene, but the foreground is indistinct, abstract, a bit ominous, and filled with yugen (mystery). He juxtaposes heavy black ink and different shades of grey wash. Although unsigned, the seal in this work is similar to one that appears in his self-portrait, which is a Japanese national treasure. Similar example Seal comparison

-

- 3

-

-

-

Thanks Piers. You are right. I think I just pulled down the wrong kanji. I think this old dodger is still alive! Not sure if there is a particular symbolism or reference for hyotan and what appears to be a noh mask, but hyotan is near and dear to me and I use a pic of this vase as the image for my home page. I love that it has a "stopper," as part of its detail. I don't see any casting lines, but it is the only object of its kind that I have had the opportunity to examine.

-

A fine Japanese cast bronze (presumed) double gourd (hyotan) bud vase with tasseled cords, a stopper and Noh Theater Demon Mask "Netsuke" well detailed around the sides with reddish-brown colored patina. The slightly recessed base is impressed with a seal mark of Mouri Motonari (元就, 1947–present), a prominent metal craftsman working out of Takaoka City in Japan, specializing in creating high-quality, handcrafted, and detailed samurai helmet (kabuto) figurines and traditional bronze, iron, and brass-based metalwork. These traditional Japanese handicrafts (Takaoka Copper Crafts) are frequently designed for display and commemoration incorporating authentic, detailed, and symbolic designs. The work is deeply inspired by Mōri Motonari (1497-1571), a famous strategist and Sengoku period warlord from the Chūgoku region, often depicting items such as the "Three Arrows" story or specific kabuto armor. In hope of encouraging three of his sons, Mōri Takamoto, Kikkawa Motoharu, and Kobayakawa Takakage, to work together for the benefit of the Mōri clan, he is said to have handed each of his sons an arrow and asked each to snap it. After each snapped his arrow, Motonari produced three more arrows and asked his sons to snap all three at once. When they could not do so, Motonari explained that one arrow could be broken easily, but three arrows held together could not. It is a lesson that is still taught today in Japanese schools and the legend is believed to have been a source of inspiration for Akira Kurosawa when writing his samurai epic Ran. Height 9 1/4 inches X diameter 3 1/4 inches.

-

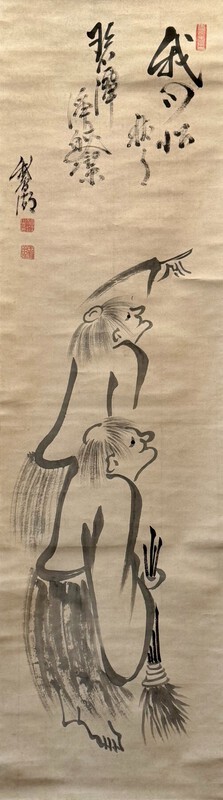

Hi Greg. Here is a write up that I took from my website: "The vast majority of his works were calligraphy from the Jubokudo lineage of Shodo established by Wang Hsi-chi (Wang Xizhi), a Chinese calligrapher of the 4th century. Yamaoka created a calligraphy manual based on the 154 Chinese characters of a poem – “The Eight Immortals of the Wine Cup” – by the Tang Dynasty poet Du Fu (712 – 770 A.D.) that is still practiced by the Chosei Zen Rhode Island Zen Dojo in the US." Part of the difficulty with translating Yamaoka's brushwork is that it is highly idiosyncratic, although extraordinarily consistent. He also mixed kanji with katakana in many of his works. Although his "calligraphy manual" is useful, it is only 154 characters long. It is often said that to read a Chinese newspaper requires fluency in at least 2,000 characters. And if we suspect that the work on the panels that I posted is taken from ancient Chinese poetry, we are now talking about this language in the hands of (e.g.) Tang dynasty poets! The only person I know of who was truly an expert translator of Yamaoka is John Stevens. I still mourn his recent passing. No longer can I reach out to him for help with translation. However, I continue to work on these panels whenever I see something familiar such as the kanji for "wind" as the second character in the last column. It gives me a cross reference. Interestingly, the Chosei Zen shodo practice uses the Yamaoka manual as a template for learning calligraphy as part of and to enhance zen practice. Breathing and form are very important in shodo, as they are in zazen and budo. I originally came into contact with Chosei Zen while seeking assistance with a Yamaoka work. No one there can read a complex Yamaoka work. In fact, I'm more familiar with Yamaoka's usage and range. As it turns out, they practice shodo without needing to know the meaning of the calligraphy--even purposely ignoring the meaning of the kanji in the process of focusing on the act of creating a beautiful brushwork that reflects the state of their minds in samadhi. So, I disagree with your statement that "calligraphy without translation is mere decoration, devoid of meaning." One of the remarkable qualities of a work by Yamaoka (or Otagaki Rengetsu for that matter) is that it is readily apparent that they were the work of a martial artist. His execution of characters on this particular panel is a perfect example. The columns and character spacing are perfectly aligned, one character flowing into the next without a break. The hand is sure, fast, and perfectly controlled as if he were engaged in a sword duel. His calligraphy has been analyzed under microscopic examination to reveal the absolute confidence in which the ink has been laid down on paper. Like a fortress, there is no way to attack or penetrate these lines from the outside. The panels are over 6 feet tall and stretch out to nearly 12 feet. When you stand in front of them, it is simply overwhelming. It feels like it a face-to-face encounter with Yamaoka's life force. Of course I would love to know the meaning of the poems on these panels. They will lead to other levels of meaning. Merely decoration? I don't experience them that way. One last thought. Here are two examples of the same Hanshan poem, brushed by Rinzai Zen master Gako (Tengen Chiben) and the Obaku Zen master Baisao. Their calligraphy reflects totally different pictorial styles separated by about a century and with different intentions--both admirable. Same poem/meaning. 吾心似秋月 (Wú xīn sì qiū yuè) - My mind is like the autumn moon, 碧潭清皎潔 (Bì tán qīng jiǎo jié) - clear and bright in a pool of jade, 無物堪比倫 (Wú wù kān bǐ lún) - nothing can compare, 教我如何説 (Jiào wǒ rú hé shuō) - what more can I say

-

Actually, believe it or not, I learned yabusame in Kamakura Japan. Mostly riding a wooden horse for training indoors and then... I don't really need the Ebira to hold ya when practicing on a makeshift wooden horse. I just tuck the ya into the straps of my hakama, but the Ebira is fun. I practice Heki Ryū Bishū Chikurin-ha, which Shibata sensei brought to the US in the 1970's at the height of Western interest in all things Japan. There is a National Geographic documentary about him that was heavily viewed. The yabusame is another story. I got a chance to do kyudo practice with a group on a visit to Kamakura. To my surprise, they had a wooden horse in their dojo, which they let me try. When I was coming back from a 7 year sabbatical in Singapore, I took a significant amount of time off to train in Japan (both Kyoto where Shibata sensei's main teaching line remains, and Kamakura). I didn't even know how to ride a horse, so it was quite an adventure. I have made some of my own wooden turnip shaped arrowheads, which got me interested in the whistling variety. This is my makiwara just outside my covered patio and the 8 mm bamboo practice ya that I make from scratch. I do enteki on our back property that overlooks a nature reserve (just gorgeous). I am making finer sets of 9 mm ya fletched with the highest grade wild turkey feathers with horn nocks and silk wrapping to gift to teachers for ceremonial shooting.

-

Tengen Chiben (1737-1805), whose art name was Gako (meaning "Goose Lake"), was a second generation Rinzai monk in the Hakuin Ekaku tradition. He lived and taught at temples like Onsenji and Nanzenji, leaving behind influential ink paintings and calligraphy that showcased his deep understanding of Zen Buddhism. He was known for his expressive figural paintings, especially of Zen eccentrics like Kanzan (Chinese Hanshan 寒山), "Cold Mountain") and Jittoku, following the tradition of Hakuin's lineage. However, this painting and accompanying inscription of one of Hanshan's most famous poetic quatrains (#5) shows his lively and individualistic brushwork. The dark outline of their bodies, eyes, and handle of broom stands out from the gray-wash of their clothes, serves as a compositional device to emphasize attention on the moon above. Interestingly, Gako substitutes the less formal Wǒ (我) for the first character Wú (吾) in Hanshan's poem, both of which have the same meaning. The verses connect the moon's perfect, untainted reflection to the enlightened mind (Buddha-mind or kensho), representing clarity, emptiness (mu), and the universe: 吾心似秋月 (Wú xīn sì qiū yuè) - My mind is like the autumn moon, 碧潭清皎潔 (Bì tán qīng jiǎo jié) - clear and bright in a pool of jade, 無物堪比倫 (Wú wù kān bǐ lún) - nothing can compare, 教我如何説 (Jiào wǒ rú hé shuō) - what more can I say1 This specific piece was purchased in auction for a mere fraction of its real value, perhaps unrecognized as the very example from a private collection that was published in Stephen Addiss' seminal book.2 1The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain. Translated by Red Pine; publisher Copper Canyon Press, Washington (2000), pg. 39 2The Art of Zen: paintings and calligraphy by Japanese monks 1600-1925. Stephen Addiss; publisher Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York (1989)

.thumb.png.7321796cea7274fcb1f468827a388a56.png)

.thumb.png.61a4a1903beba0c064cf6110aafed2d1.png)