JohnTo

-

Posts

268 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Posts posted by JohnTo

-

-

Hi guys,

Can you help with the gold inlaid signature on this iron tsuba? The signature is not in a seal, but the cursive (correct term?) style of writing has me lost with the first character. It is a bit like Kaze/fu but I don’t think so. The second kanji appears to be ‘chika’

A description of the tsuba is as follows, and my best guess as to school would be Kaneie.

A maru gata iron tsuba with a black patina, slightly dished with rounded edges and the usual pair of kogai and kodzuka hitsu (the kodzuka hitsu is lined on the straight edge with apiece of shakudo). The nagako ana is rather wide and is fitted with copper seki gane to top and bottom. The tsuba has a simple design, carved in shallow relief (sukidashi takabori) and depicts a peasant in a straw cloak and hat, with a hoe over his shoulder, crossing a low bridge on stilts. Above the man is a flock of 15 birds (geese?) flying in squally weather, as depicted by driving rain and bamboo bending in the wind (a similar scene on birds, wind and bamboo is shown on the reverse.

The design is plain and without embellishment with, for example, gold nunome and yet the signature is inlaid with gold, even though it would be hidden by the seppa. The cursive script makes it difficult to read, the first character is unknown, but the second appears to be ‘chika’.

Height: 7.8 cm, Width: 7.6 cm, Thickness (rim): 0.4 cm

Thanks

John

(just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

Luca,

I've been away from the NNB for a while and have just discoved your Kaga pdf. Excellent piece of work with kanji in the texts and references at the end. Published info don't get better than that. Thanks for all your work and making it available to all.

I was interested to see the tsuba in B.5, C with a fuchi/kashira attached to it, in the Boston museum. I have just bought a sukashi tsuba with a kashira rivited to the seppa dai and was thinking to myself 'What sort of idiot would do that'. Guess there were at least two.

great work, thanks again, John

-

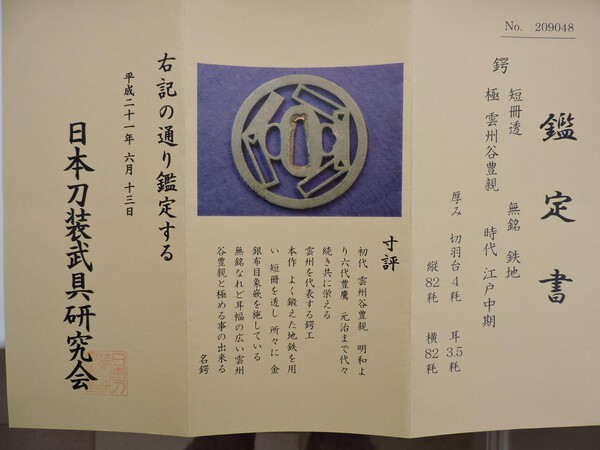

I bought a tsuba with a similar broad rim and flat profile that came with an ‘origami’ (not shown in auction), that turned out to be a NTKK kanteisho. The origami did not arrive until about a week later, during which time I could not assign a school or maker to it. In my limited experience the unusually wide rim made it difficult to assign. NTKK says it is Unshu Tani Toyochika. My inventory notes are below and pics for comparison are attached. Anyone got a better translation for the description of the design, Tan-satu-to, a half/short (tan) counter of books (satsu) that is open/transparent (to)?

This large tsuba is of round flat sukashi form with what appears to be three carpenter’s squares cut out of a flat iron plate. The kanteisho describes them as tan-satsu-to (literally. Short-counters for books-transparent) The width of the rim is unusually wide, indicating that this is not the work of most of the sukashi schools such as the Kyo, Akasaka, or Owari. The tsuba is unsigned, but came with a box containing a label, in Japanese, attributing the tsuba to ‘Unshu Tani Toyochika’, i.e. Toyachika of the Tani school in the province of Unshu. The lot was also accompanied by a NTKK (Nihon Tosogu Kenkyu Kai) origami that arrived a week later confirming this attribution (see below). The Tani school was established in the Izumo no Kuni by Jirosuke Toyochika (working in the Meiwa period; 1764-72) and his son Toyoshige (working in the Kansei era; 1789-1801). There is also some gold nunome which is mostly worn away.

The translation of part of the NTKK kanteisho, reading columns from right to left, is as follows:

kantei-sho (鑑定書) - Appraisal No.

tsuba (鐔) Tan-satsu-to (open half counter for books?), mumei (無銘), tetsu-ji (鉄地) – unsigned, iron XXXX

XXXXXXXX ?Unshu Tani Toyochika

Jidai (時代) Edo-chūkji (江戸中期) – time of production, mid-Edo period

厚mi - DimentionsSeppa Dai 4 mm, Mimi 3.5 mm

Height: 82 mm Width: 82 mm

Sunpyō (寸評) – Brief Review

XXXX Shodai Unshu Tani Toyochika. Showa yori roku dai Toyotaka First generation Unshu Tani Toyochika until the Showa era sixth generation Toyotaka.

Genji (1864) made daidai zokuki tomo ni sakaeru – Until Genji (1864) generations prospered together.

Unshu o daihyo suru tsuba ko/ku-hon/moto saku- Representations of Unshu styles were made.

Uki no tōri kantei-suru (右記の通り鑑定する) – The above is the summary of our appraisal.

Heisei 21 year sixth month 13th day (June 13, 2009)Nihon Tōsōgu Kenkyū Kai (日本刀装具研究会)

Best regards, John

-

I seem to have a penchant for buying cast iron tsuba via commisison bids at small auctions where the photos are not very good. Here is my latest. I would challenge Ford's supposition that these are modern, based upon the context in which I bought these. I think that all three came from mixed lots that contained authentic pieces, some from quite large groups of lots which I assumed were from deceased estates. So I think that they were acquired many years ago when tsuba were cheap and there was no demand fo modern fakes. Here is the description from my inventory.

This sukashi tsuba appeared to be an Akasaka (or possibly Nishigaki or Higo) tsuba from the poor photograph on the auction website. However, upon receipt it was obvious that this is a cast iron copy of an Akasaka design, probably made in Japan in the 19thC as a cheap sword fitting for an impoverished owner. The tell tale signs of casting are the glossy patina, flaking of the surface around the rim and fine ridge line near the centre of the piercings for joins in the mould. There are also two circular marks either side of the top of the seppa dai, which look like welding spots. I would surmise that these had been done at a later date, possibly to affix the tsuba to something as decoration. See ##019 and ##024 for other examples of cast iron tsuba.

Provenance: Canterbury Auctions, Wednesday 10th April 2018, Lot 594

Height: 7.0 cm

Width: 6.6 cm

Thickness: 0.65 cm rim

Some bids are diamonds, some bids are dust/rust. Its good to admit ones failures on NMB, quite cathartic.

All the best, John

-

Thanks Ford for the clarification. It is interesting to look at descriptions of 'sandy brown' alloy tsuba in various catalogues and books. One auctioneer will describe nearly all such items as brass, another as sentoku and another as shinchu. I guess it needs someone to publish a book on Japanese alloys. Then we have differing compositions of brass, anything from 5% to 40% zinc, sometimes with a dash of lead, etc. So to misquote Star Trek 'Its brass, John, but not as we know it'

Looking forward to the book, thanks again for the comment, John

-

1

1

-

-

Here is the tsuba im my collection that i think embodies wabi sabi. i think that it is Kanayama and I've posted it before in more detail. The iron is roughly finished, looking heavily rusted, but its not. Spokes have been removed to leave the simplest of designs. In summary a natural looking piece of old iron with lots of imperfections that has a lonely, empty feel to it. Wabi sabi as far as I'm concerned,

Best regards, John

-

Thanks for the replies. Pete, Bruno, Curran, Steven: Shonai Shoami. That is a branch of the Shoami that I am unfamiliar with. The few examples that I have found so far show a wide variety of styles, so I would not have attributed this tsuba to that school. There were a couple of examples of similar workmanship, so thanks for the info. Its what the NMB is for after all, sharing ideas and learning.

Pete. I'm not sure that I agree with you saying that they are just punch marks. The bottom ones do not seem to have any significant effect on the size of the nagako ana. I think that they are more for decoration, as I have seen on other 19thC tsuba made for export and have never been on a sword. Nagoya mono tsuba (cheap copies of Mino Goto) have a characteristic pattern of 10 large punch marks in all the half dozen patterns I have seen (treasure ship, pagaoda, Ono no Komachi etc). See discussion on NMB a couple of months ago. Although large marks, they are all the same pattern and obviously not for resizing the nagako ana. I suspect that these flower punch marks were used in several workshops in Edo.

Thanks again for the info everyone, best regards, John

Just a guy trying to learn and sitting at his PC waiting for the postman to deliver his next treasure from Japan

-

I’ll ask the usual questions at the start, namely any ideas on the school and maker, plus any ideas about the theme of the design, which I have not seen before?

This large maru gata tsuba appears to be made of brass (sentoku) or closely related alloy giving it a slight red-brown patina. The scene continues over both sides and depicts a hanging scroll falling off what I assume is a wooden, two legged easel (in shakudo?) with a tying ring at the top. There is also a shakudo vase with a golden flower and long tapering leaves (daffodil?). This vase is on a separate, slightly sunken, lightly hammered, chocolate brown area, separated from the main body by a zig-zag line, possibly to indicate a violent event, e.g. perhaps the scene has been disrupted by a sudden gust of wind. Like a good fitting toupee, I cannot detect the join between the sentoku and the chocolate brown area, so perhaps it is not inlay, but a change in patination.

The tsuba is fitted with a shakudo fukurin and has a pair of kogai hitsu ana. Staining and slight damage around the nagako ana indicates that this tsuba was once mounted on a sword and was not just a piece made for presentation, or the 19thC export market.

The loose hanging scroll depicts Shoki (the demon slayer) picked out in fine gold inlay on a charcoal grey background (representing a sheet of paper), which is framed in sentoku(?) and copper, all on a shakudo scroll. Even the end of the pole at the bottom of the scroll is tipped in silver. The vase is finely inlayed with gold and the flower (daffodil) is probably gold. Altogether, a finely crafted piece of work, but unsigned (not that signatures can be relied upon).

I reckon that the tsuba was made about 1800, give or take 50 years maximum. There were lots of skilled kinko artisans around this time, many signed their works, but some did not. There maybe two clues as to the school. On the face of the tsuba there are three flower shaped punch marks, one at each bottom corner of the nagako ana and a double at the point. None is complete, but may be a ca. 14 petal chrysanthemums. They look like tagane mei (chisel name) rather than attempts to modify the shape. The other clue is the representation of the scroll, which wraps around the rim to appear on both faces of the tsuba. To judge from auction catalogues etc., continuing the design on both the front and back of mixed metal tsuba seems to be in vogue during the first half of the 19thC.

One of the aspects that I love about collecting tsuba is figuring out the scene that they depict. At the time they were made, I expect that the themes would have been well known to the average Japanese, but many have now been forgotten. I spent a long time wondering why someone would want to portray a scroll being blown aside by a gust of wind. Then I watched a Japanese version of the 47 Ronin and think that I may have found the answer. The Ako Incident, in which the 47 Ronin avenged their lord’s death by killing Lord Kira took place on 30th January 1703. OK, that was winter, but an early daffodil could have been placed as a decoration indoors in a vase, as shown on the tsuba. The popular version of events has Lord Kira hiding in a charcoal store out in the back somewhere. I can’t imagine the main charcoal store being close to Kira’s bedroom and maybe the story was exaggerated to further blacken Kira’s name (sorry guys, could not resist that one). A different version has Kira being found in a secret courtyard behind his bedroom, hidden by a large scroll, that maybe held a small quantity of charcoal for the bedroom heating. Perhaps the design on the scroll (Shoki, killer of oni) represents Oishi Kuranosuke killer of Kira.

I have found flower punch marks (literature examples) on tsuba by Hagiya Katsuhira (Mito school, ca. 1870), Ichijuken Teruaki (Kato school, ca 1860), Funada Ikken (Goto school, 1844), unsigned Mino Goto, unsigned Hamano school (19th C), Oishi Akichika (1854, Oishi Akichika making a tsuba alluding to Oishi Kuransuke, see above?, Nah, coincidence) and Kano Natsuo. So I guess flower punches were used by many of the tsuba artisans in the 19thC, which probably reflects fluidity between the artists and workshops, many of which were in Edo. I would imagine that artisans fashioned their own tools and that making flower punches was part of the training in one or more workshops.

I gather that many of the 19thC kinko artist used designs supplied by other artists on paper and I believe this is why we see so many 19thC kinko tsuba with apparently unique designs; there were so many to choose from. To my aesthetics, it makes a welcome change from the same old Kinai dragons, aoi leaves, carp, etc. of the 18thC and similar repetitious designs of other schools. Unfortunately, many of these high quality kinko works are unsigned. Why was this?

My best guess is that this tsuba was made about 1800 in one of the Edo workshops (Goto, Yokoya, Nara, Kono), but this is not based upon handling similar examples, so feel free to challenge.

Height: 7.8 cm; Width: 7.65 cm; Thickness (rim): 0.55 cm; Weight: 168g

Best regards, John

(just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

Thanks Bruno,

Good to see another example of the basic pattern. Yours has a flatter profile and with the brass inlay I agree that makes it likely to be Heianjo.

regards, John

-

Thanks for the replies. Geraint, you are probably right about the 'fukurin' and it is nunome (inlay attached by cross hatched grooves). Problem is that the exposed areas have slight corrosion and I can't definitely detect the anchor grooves. Opinion seems to remain with Echizen, though others had very similar styles. As I look in my cabinet of tsuba, this one definitely reflects the light more than my other black iron tsuba. I guess just a more careful attention to getting a smooth shiny surface finish rather than the quirk of some other scool.

Best regards, John

-

Hopefully it is difficult for NMB members to differentiate between the leaves of cannabis and acer palmatum, both commonly have 7 serated sections to their leaves and are virtually identical when taken out of natural context, e.g. depicted on a tsuba. I'm told that the leaves can be told apart by the smell when burnt, but I have no experience of burning maple leaves. Besides, its difficult to burn an iron tsuba (not that I would want to).

Just for you delectation I attach pics of a tsuba of mine which includes a beech tree branch with nuts, a single ginko leaf, a pine cone and a cannabis/maple leaf. As the others are woodland plants, I assume it to be maple. The description of the tsuba is:

This iron sukashi tsuba depicts leaves and a pine cone carved in three dimensions and is highlighted in gold nunome zogan (hammering gold leaf into a criss-cross engraving). The tsuba is 'signed' Nagato (Choshu) Hagi Ju Sakunoshin Tomohisa, who was the first generation master of the Yazu (often pronounced Yaji) School and active in the Enpo (1673-81) and Jokyo (1684-88) periods. The translation of the signature is ‘Nagato Hagi Ju’: ‘Resident of Hagi in Nagato (Choshu) province’, ‘Sakunoshin Tomohisa’: ‘Tomohisa, personal name Sakunoshin’. Seven generations of artisans, all using the same kanji for Tomo as the first part of their names, are listed by Markus Sesko and were active until about 1850.

I have seen other examples of this design, one signed Rakurakusai Tomosada, so I guess it was popular.

Height: 7.5 cm, Width: 7.3 cm Thickness: 0.4 cm

Best regards, John

-

Lovely tsuba, if I hold my breath long enough and turn purple, maybe my wife will let me buy it. Can't say if its genuine, but the NBTHK think so.

I've seen several iron Goto tsuba come up in auctions. One I have found is Lot 167, Compton I, a late Goto school daisho, with NBTHK kicho for the dai and sho. They were made by Goto Ichijo (1791-1876) and signed Toki ni nanajugo raku Hakuo saku and Kaku hoku kyo Hakuo saku. According to Christies he signed Hakuo on iron tsuba because 'Even at this late perion the traditions of the Goto school were such that the master of the school could not use his official Goto names on an iron tsuba. This prohibition did not extend to accompanying documents and tomobako, where the formal signature was considered appropriate.' So maybe Goto Seijo broke the rules, or they had not been formalised when he was around (mid 1600s)

Regards, John

-

-

Hi guys

This maru gata iron sukashi tsuba has a design of large gunbai (war fan) enclosed by a square profiled mimi. Dimensions: Height: 7.05 cm, Width: 6.75 cm, Thickness: 0.4 cm

The tsuba is unsigned but I have tentatively attributed it to the Kinai Echizen school based upon the gently sculpted fan and chords in katachi bori (carving the design in the round into the surface of the iron plate), black patina and fine gold nunome inlay. The Echizen Kinai did not seem to be shy about signing their work, and as this is a design outside their usual production of dragons, aoi leaves and carp, I would have expected it to have been signed; if it was made by them. My alternative assignments are (Bizen) Shoami based upon mumei Echizen style tsuba I have seen, or possible Ono (guessing here). The tsuba has a pair of kogai hitsu, one of which is plugged with shakudo. I would date the tsuba a second half of the 18thC. But please challenge my attributions.

There are several interesting features about this tsuba about which I seek info and comments, as follows:

Gunbai (fan) design: The large gunbai that takes up most of the space seems to be an unusual design. I have only found illustrations of a couple of tsuba with large gunbai, although tsuba with small gunbai incorporated as part of the design are more common. The central stem of the gunbai is curved to the left, as are the vast majority of representations that I have seen and may therefore represent a kamon (variant of of Okudaira mon?), rather than a symbol of military authority. Additionally, the kara uchiwa (Chinese fan), also a symbol of authority and I believe was one of the items in the takarabune (treasure ship of the gods of good luck). I have found a kamon listed as ‘maruni to uchiwa’ (circle and fan?) very similar to the design on this tsuba, but without any clan attribution (see picture). Any information out there regarding gunbai/uchiwa fans and as to why the central stem is often shown curved whereas real gunbai stems are straight? Also what is the difference between a gunbai and uchiwa fan?

Patina: One of the kantei points that I have used in attributing this tsuba to Kinai is the black patina, rather than the russet brown of many other schools. However, the patina on this tsuba is glossy and resembles shakudo, whereas the patina on the couple of other Kinai tsuba that I have is dull. The patina appears thin and has been rubbed off much of the seppa dai, exposing the shiny iron underneath. If it was not for this evidence of wear I would have been tempted to say that the tsuba had been repatinated by a gunsmith, as it looks like the black finish of modern gun. Perhaps the original owner wanted an iron tsuba to look like shakudo, in accordance with the Edo court requirements.

Mimi: The mimi bares traces of a silver alloy fukurin, which has mostly worn away and exposed the underlying iron, resulting in slight pitting and corrosion. I’m not sure if the coating is substantial enough to be called a fukurin as it appears to have been rather thin. The remaining metal has a white shiny appearance, like silver, but I hesitate to call it silver as I would expect silver to be black after all this time. I have tsuba with ‘black silver’ and ‘silver silver’ on the same piece, so I assume that ‘silver silver’ is actually an alloy that does not darken with age (Over to you Ford?) The thin fukurin was probably the cause of the corrosion around the mimi. I imagine that once the fukurin became damaged, and the underlying iron was exposed, a galvanic cell (battery) would have been created between the iron and silver in which the iron (anode) corroded (rusted) once the tsuba became wet (rain, sweat). The mimi also bears traces of pine needle shaped gold nunome.

Best regards, John

(just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

1

1

-

-

I wonder if odd shaped nagako ana was to fit around the spur on a jitte (sword breaker) or hachiwari (helmet breaker). I know that jitte don't normally have tsuba, but some Meiji policeman might have quickly added a crude tsuba.

Regards, John

-

Nice tsuba. The seppa dai looks namban style but the main part looks like Bushu/Efu (Edo) carving. An interesting feature is the numerous tiny ‘silver nail heads’. I’ve got these on a mumei tsuba (see pics) of chrysanthemums which I attributed to Bushu, Shoami or Choshu schools. Choshu was least favourite as I believe they were not great on gold nunome around the mimi. Aoi-Art has a similar style tsuba (F16179) to mine for sale with silver nail heads and a NBTHK Hozon attributed to the Kyo-Shoami school. I don’t know how common ‘silver nail heads’ are as a decoration, or if they can be used as a kantei point. But that’s my best guess, a mixture of styles but carving in the round plus silver nail heads gives Shoami.

Best regards, John (just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

The shiirimono issued deepens with more examples being shown above, some with NBTHK papers.

I have found three in the Compton Collection part III catalogue (lots 31, 32 and 33), where they are described as Nagoya-Mono tsuba and made of nigurome plate. The footnote to lot 32 says ‘This style of tsuba was made to resemble the work of the Mino Goto school. The demand for Goto style work was so great in the mid-Edo period that the Goto artists could not keep up with demand, so various artists in Nagoya helped supply pieces in the Goto style.’ The three pieces were dated as 1700-1750 and sold for $440 to $880 each; not cheap!

Unfortunately neither the Compton catalogue nor the Nihon To Koza VI glossaries define what the alloy nigurome is. The Wikipidia enlightens us with ‘shakudo…entailed the heating of copper, addition of fine gold, and some addition of shirome, a by-product of copper production containing iron, arsenic and other elements. In the Edo period, it appears that the process may have used nigurome rather than copper; nigurome being itself a pre-made mix of copper and shirome. The resulting alloy was then allowed to rest in ingot moulds in heated water, before being shaped, and annealed at around 650 C. In cooled form, the metal was then surface-finished using the niiro process. The modern process tends to omit the shirome, working with copper and gold, and other additives directly if needed.’ For a detailed article of shakudo and nigurome see reference 3 in the Wikipidia article, by Oguchi (Öguchi, H. Gold Bull (1983) 16: 125. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03214636).

Oguchi states that the making of shakudo was a complex process and a closely kept secret within the Goto family. For example, using the wrong sort of charcoal in the furnace resulted in shakudo that took on a grey, rather than black patination. So it would seem likely that the Nagoya tsubako used nigurome, an alloy without gold, as they were unable to make good quality shakudo (A project for Ford and his buddy with the XRF analyser?). In my mind it explains why the seppa dai of most of Nagoya-mono tsuba that I have seen (mainly photos) are bronze coloured rather than blue-black.

While I can accept that these tsuba were probably made for poor samurai who could not afford the genuine Goto products, I’m still left with the problem of the nagako ana. Many of the photos that I have seen show the characteristic 10 punch marks and the few that I have handled show no signs of filing and scraping as a result of fitting to individual swords. Maybe they were made for mass produced blades that had identical nagako (unlikely). Perhaps the tsuba were fitted by packing the nakago ana with a soft material (paper?) and also used a soft material for the seppa that did not scratch the tsuba.

Although I have seen no supporting evidence, I would not be surprised if apprentices from the Goto school were shipped off to Nagoya to produce these tsuba as part of their training. Maybe the Goto family owned the Nagoya ‘factories’. After all, it would be better economics to have a trainee earning money making inferior quality tsuba for someone else, but honing their skills before being allowed in the Goto workshops. It would also explain why some of these tsuba have NBTHK papers.

From now on I shall be referring to these tsuba as Nagoya-mono, as it sounds a lot better than ‘off-the self’ (shiirimono). I no longer consider them to be fakes, just tsuba produced by workshops that were inferior to the great Goto artists of the time. One thing still concerns me. A newbe tsuba collector like myself has been able to find out a lot of information about these tsuba in a short time. Established dealers, with far more knowledge than I, often seem to be implying that these are Mino/Goto works. As someone who has used the Japanese dealers’ websites to improve my knowledge of tsuba, I shall exercise more caution when reading descriptions. I recall a zen monk who would look in the mirror each day and have a conversation with himself along the lines of ‘O monk’ ‘Yes sir?’ ’Don’t be fooled’ ’No sir, no sir’.

Best regards, John

(just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

-

1

1

-

-

I thought that I would revive the discussion on shiirimono as I became interested in Mino Goto lookalike shiirimono tsuba recently after I purchased two in a job lot of tsuba at a local auction. Not knowing about shiirimono knockoffs I thought that they were just poor quality Goto tsuba. Having studied my examples and finding further info on the NMB etc., I now share my observations, thoughts and questions. Probably a timely revival as several examples have come up for sale recently, one being described as ‘rare’, ‘Mino school’, ‘shakudo’ and sold for $360.

Searching the Internet, NMB, auction sites and dealers’ sites I have found at least duplicate examples of five different designs, all mokko shaped, namely;

- Treasure ship (see my first example) in which the kanji ‘hoo’ for treasure is displayed on the sail.

- Four chrysanthemums (see my second example, which looks like it has been painted black in imitation shakudo)

- Pagoda

- Lady calligraphy writer (described by one Japanese dealer as the 7thC poet Ono no Komachi. See screen shots of two examples from on-line auctions last week)

- Dragon in waves

Anyone got other examples?

At first sight the duplicates of each design look identical, but on closer examination differences in the finish can be seen. The gilding pattern and kanji on the sail of the treasure ship is different on my tsuba from another published example. The pattern of nanako punch marks show differences in other duplicates, indicating that they were applied by hand. Thus rough cast tsuba were subjected to finishing by individual craftsmen, who while not the best Goto craftsmen, nonetheless took some care when working (I’d hate to have made my living as the ‘nanako guy’). This has been suggested before (Junichi) and the two pics of Ono no Komachi tsuba that have been on sale at recent on-line auctions shows the differences in quality of the finish.

The seppa dai on these tsuba is often a chocolate brown, indicating that the tsuba were cast in bronze, an ideal metal for casting, and not the shakudo of the Goto school (as sometimes stated on adverts for tsuba for sale).

Another observation that intrigues me is the seppa dai and nagako ana: they usually show no sign of being mounted on a sword, the seppa dai is unblemished and the nagako ana shows no sign of wear or filing (I did see one with sekigane). However, most show a distinct pattern of punch marks, three at the bottom (mune), two either side at the bottom and three at the top. As pointed out before (Mauro) these appear to be a signature (tagane mei) of the factory(?) rather than an indication that they were used to modify the nagako ana when fitting to a blade. The ten punch marks show some variation in the exact placement and so were not stamped by a machine.

These observations prompt me to ask several questions, the obvious ones being who made them and when were they made. Opinions have already been given on these. The other question I have is ‘Who were they made for? Poor samurai, Japanese tourists, Western tourists, export market?’

My initial thought as to the purchasers of these tsuba were poor samurai and others who could not afford quality Goto fittings. However the majority of examples that I have seen do not appear to have been mounted on blades.

I don’t get the impression that middle class Japanese in the pre-Meiji period were collectors of souvenirs, or were great tourists, but my knowledge here is lacking.

There was no significant influx of Western tourists until the Meiji era and these were few and moneyed people. After the haitorei I imagine that the price of sword fittings collapsed and those few western collectors buying tsuba were presented with a vast array of good quality items and would not have been interested in shiirimono.

Skilled kinko tsuba makers were turning out good quality bronze figures at this time and I doubt if they were making cheap tsuba as a sideline, e.g. Miyao Eisuke workshop in Yokohama. However smaller workshops were probably churning them out and throwing them in with job lots of genuine and fake Japanese antiques being exported to the west at the end of the 19thC. Japanese stuff was all the rage in Europe at this time.

Although I have no specific interest in collecting cast tsuba, that makes two ‘Mino’ tsuba and three cast iron sukashi tsuba that I have bought without realising what they were at the time. But, from published examples of shiirimono in the collections of experienced collectors, I guess that I am not the only one who has acquired examples by accident. Ah well, its all part of the learning process.

-

1

1

-

Hi Grev,

The number of copies sold in the UK has now risen to at least 7; I received my copy last week. Overall, I’m pleased with the book and must congratulate you on your efforts. I have sometimes wondered if it was possible to get involved in working through the collections at the British, or Victoria and Albert Museums to photograph and write on-line descriptions better than ‘iron tsuba, Japan’. A monumental task. It’s a dream, but you have done it with the Birmingham collection. Not a great collection (some have more rust than my first car), but probably of more relevance to the average collector, like myself, as the quality is the level we are likely to find affordable when tsuba come up for sale. The Sasano books, Compton collection catalogues etc. are fine for the rich collector, but for us of more modest means this book hits the spot.

The book is useful for a collector to compare their tsuba with those in this collection. From my brief reading, I did not always agree with the attributions. But then I also wonder at NBTHK attributions (I’m just a beginner, but like to challenge accepted thoughts and this, to me, is what collecting is about). I see that Grev also had second thoughts. Two photos of tsuba 14930M944 appear on page 78 attributed to the Nara Hamano branch, then reappear on page 110 attributed to the Shonai Shoami school.

You asked for comments on the contents and here are a few I picked up on. Please don’t feel I am being over critical, I just hope they will be of help.

- The material and patina of the tsuba are not included, though obvious in most cases.

- Tsuba showing the Yatsuhachi Bridge are sometimes described as the 7-plank bridge at the Mikawa iris marshes (1930M737 p9 , 1930M1115 p97). Yatsu is Japanese for 8.

- The three piercings on tsuba 1930M611 are described as gourds, whereas the usual description (used elsewhere) is kukurizaru (self-righting monkey toys) representing Daruma and no doubt popular because no matter how hard you knock them down, they get back up.

- Tsuba 1930M767 and 1930M669, p 124, dated 1500 and 1525, respectively, are attributed to the Umetada school. Umetada Myoju’s dates are given as 1568-1631 and I don’t believe his predecessors used the name Umetada.

At least it shows I'm reading the book and not just looking at the photos.

Best regards, John

(Just a guy making observations, asking questions and trying to learn)

-

Just wondering if the christian cross is a later addition. The photo is a bit fuzzy, but the cross does not look quite summetrical. Nice piece though.

regards, John

-

Hi Guys,

My tsuba collection seems to be a bit sparse on the rabbit front, but here are a for your delectation.

The first one shows an area of open grassland. Unfortunately the rabbit been scared off, but he has left a small pile of droppings in the lower left hand corner.

The second tsuba shows a monk about to butcher a rabbit in order to make a rabbit stew for his fellow acolytes. There is a bowl of boiling water in the background with what appears to be a cabbage leaf, so the cooking is evidently well underway.

But seriously, I have posted this tsuba before (2013). It depicts the zen monk Tanka (d. 834) burning a carving of Buddha at the Yeren temple. It is signed/inscribed Funakoshi Shunmin, with kao (an alternative name for Ikedo Minkoku, 1828 -1916).

Serious question. The face and arms of Tanka are silver and were bright, due to overcleaning, when I bought it. These have now tarnished to black. However the edge of the axe is still bright. I thought that it was silver, but as it has not tarnished, has anyone got an idea what silver alloy might have been used?

That’s all folks, John

-

2

2

-

-

I feel a bit more confident calling this a Kanayama tsuba, because that what was written on a piece of card in the box lid! I bought this tsuba at another general art auction and it looked like it came from another ‘deceased estate’ of a Japanese collector, as there were a couple of good netsuke in adjacent lots. The card in the box lid stated ‘Tokubestu-kicho papers { now between hozon and tokubetsu-hozon ] reading 雪竹雁繋透鍔 Secchikugan-tsunagi sukashi tsuba [ sukashi-tsuba with connected {tsunagi} motif of snow, bamboo and wild geese }; mumei [ Kanayama ] iron, maru-gata, ji-sukashi’. The kanji are for snow, bamboo, wild geese, connection, sukashi and tsuba (I’ve shown a different kanji for tsuba as I can’t find the version shown on the card). I think that the statement ‘Tokubetsu–kicho papers [now between hozon and tokubetsu-hozon]’ indicates that the certificate was issued between 1950 and 1982. A similar worded tie-on label was also included. Unfortunately the NBTHK tokubetsu-kicho paper was not included with the lot, though I did ask the auctioneers to enquire as to its whereabouts from the vendor. No luck. As the tsuba was not expensive, the phrasing of the label was ‘NBTHK format’ and because of the way it turned up at a small auction house, I have no reason to doubt that the card and collector’s label were genuine and that the NBTHK papers were unknowingly thrown away during a house clearance. Does anyone know if a replacement can be obtained from the NBTHK?

The size of the tsuba is Height: 7.95 cm, Width: 7.85 cm, Thickness: 0.45 cm centre, 0.4 cm rim.

The tsuba is exactly as described on the label and I am happy with the Kanayama attribution. Owari might have been my choice. For comparison, Seiyudo has a similar Kanayama tsuba for sale. Both tsuba have three design elements consisting of snowflake hitsu ana (but joined differently to the rim) and symmetrical patterns at the top and bottom that are slightly diagonal. ( The snowflakes, karigane and bamboo are placed in symmetrical pairs, north-south and east-west, around the tsuba, typical of Kanayama, Kyo, Owari and other sukashi schools. I think that the spots on the rim are tekkotsu, but I’m not sure. These are about 1 mm, not large and certainly not the ‘exploding’ variety of Kanayama fame that I have seen described. If this was a sword, rather than a tsuba, I would describe them as nie, especially as they are almost flush with the surface. Once again I am going to shoot from the hip for an explanation, with no corroborating evidence. I think that the tsuba plate might have been covered in clay before the yakire and quenching, just like a sword, with a thin layer around the edges resulting in martensite deposits around the rim. A clean up on a flat stone to ensure the surfaces were flat would have resulted in the ‘nie’ type tekkotsu being exposed. It was difficult to photograph the effect, so it may not be clear. The tsuba was then patinated. Hey, maybe I’m completely wrong, but at least I have thought about it.

The nagako ana has two layers of sekigane at each end and also has areas of heavy hammered indentations to reduce the size of the nagako ana, indicating that this tsuba has been mounted on several swords. However, IMHO, I think this tsuba is no older than about mid-17th C, the finish is too refined, lacking the rustic finish that I would associate with pre 17thC Kanayama tsuba. I’m still very much a novice when it comes to tsuba and most of my information comes from books.

There seems to be a level of doubt where Kanayama tsuba originated from. Sasano gives several locations. One speculation is that they originated as pieces made by the local blacksmiths in the Kanayama district of Nagoya and that they only became important and could be considered as a school after Togugawa Ieyasu moved the capital of Owari to Nagoya in 1610.

As always, comments welcome.

Best regards, John

(just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

Photos #26 Side one

#28 side 2

#29 rim

#85 nie type spots on edge of rim

-

The first tsuba that I am presenting for discussion was bought at a general art auction in which several lots of tsuba appeared, probably from a ‘deceased estate’. Foolishly I did not bid on this one as I thought that it might go for big money and I was saving for another auction. It was unsold and came up again at the next auction and I was forced to pay over 4x the same low estimate. Damn! The tsuba came in an old collector’s box and was obviously a cherished pieced. I became interested in this tsuba via a photo on the internet, despite observing that the tsuba had been modified (see below) and I fell in love with it when it arrived in the post. The tsuba is in good overall condition with no rust scabs. There were a few spots of red surface rust in the crevices, but I removed these with the aid of a WD-40 spray, dental flossing brush and kitchen tissue, followed by drying on a radiator to remove traces of WD-40. I rather like WD-40, a fish oil based product, as it is designed to get behind rust and disperse water. I’m not a give it ‘a good rub with a piece of horn man’. If it don’t come off with a brush, I leave it. But then I don’t buy seriously rusted pieces. Anyone like to comment of my cleaning method?

The tsuba is a simple round iron sukashi (Height: 7.95 cm, Width: 7.85 cm, Thickness: 0.45 cm centre, 0.4 cm rim) with a dark, almost black, patina and two kogai hitsu ana. The nagako ana has a small copper sekigane at the narrow end and just two small punch marks either side at the bottom. Evidently this tsuba has not been mounted on numerous swords. The design, as it is now, is a simple curved square or star, slightly out of true, having small curvature in the north-south axis. Quite zen like in its simplicity. I have seen this design referred to as a (silk) bobbin, but I don’t think so, bobbins are just simple wood crosses and why would a samurai choose to display a woman’s weaving implement? I’ve searched Japanese spinning wheels, but they are not like this shape. It may be a mon, a variation on the straight sided diamond shape often seen. I’m going to call it a star. Any suggestions?

However the design was not always this simple. Look carefully and you will see the stubs of pairs of bars in each of the four piercings on both the rim and central star. As far as I can see these ‘bars’ were cut off with a chisel sometime in antiquity. Perhaps it was even the tsubako, or initial vendor who did not like the design and removed them. The surface of the stubs looks smooth compared to the edges of the sukashi design, so I guess the bars were cut off sometime after manufacture then repatinated. Perhaps the kogai ana were also added at this time. Normally, I would not be happy to find that a tsuba had been modified from its original design, but in this case I feel that it has been enhanced. I even love the stubs of the bars, which could have easily been filed down and left no trace. They show the history. To my eye, this tsuba is like a zen monk who has achieved enlightenment and has emptied his mind of all extraneous thoughts. I really love this tsuba; designs do not come any simpler. Any comments about the original design and modifications?

The delicate nature of the rim seems to shout Kyo-sukashi, or possibly Owari, but I’m going for Kanayama (which some authorities say was situated in Nagoya, Owari province anyway). The main reasons are the irregular surface of the outer rim and the simplicity of the sukashi. I have seen Kanayama tsuba described as having ‘exploding tekkotsu’ due to trapped carbon exploding in the final forging process. Personally, I’m not happy with the ‘exploding carbon’ explanation, if carbon exploded when heated, the tsubako’s forge would go up, being filled with carbon (charcoal)! It could well be that the rim was exposed to excessive heating during a final heat treatment. I did a one day blacksmith course a couple of years ago and made a couple of fire irons. I overheated one piece during the final tempering and burnt similar pits in the steel (see pic). The fire iron was made from a piece of mild steel, but the surface is similar to some tsuba that I have seen for sale described as having tekkotsu, which my fire iron obviously doesn’t have. This made me wonder if this tsuba was covered in clay for the final temper, like swords, leaving a thin coating around the sides to make the iron harder, but exposing the rim to burning, like my fire iron. Alternatively, the central part of the tsuba could have been covered with sand to protect it from burning and heated on a spatula before quenching. Hardening the rim and leaving the centre a softer iron makes sense to me, especially if the seppa dai is going to be subjected to a good old bashing to change the shape of the nakako ana. Sasano quotes sources that say the open nature of Kanayama tsuba means that they are no good for defensive fighting, as so much metal has been removed. Hardening the outer rim would counteract this limitation.

I have long been interested in forging iron, perhaps it is because my father and grandfather were blacksmiths in the UK. I never had the chance to see them at work, but I guess they left iron in my blood. I have seen Ford’s excellent videos on making soft metal tsuba, but have been unable to videos showing iron tsuba being forged. Anyone seen one? Talking to a couple of local blacksmiths has given me a different perspective on forging. Use of template tools, to make life easier, is one. The kogai ana appear to be are identical and have a minute raised rim around the outside (see pic). I reckon that a shaped punch (blacksmiths call it a drift) was used to finally shape the openings and the iron pushed up around the edges trimmed off. The main sukashi shows a difference between the edges of the central star and the rim. The inner edges of the rim seem to be quite flat, whereas the cut edges around the central star seem convex or layered. Akasaka tsuba are known for their three layered sandwich construction, with a soft iron core, but I can see no evidence of joins. Could it be that the tsubako cut the sukashi design from a soft annealed iron plate (to make cutting easier) and then hardened the surface of the iron in the final yakite. If only the outside of the tsuba became hardened (martensite), the higher density soft inner core (austenite) would shrink relative to the hard steel, as in Japanese sword making where the soft back of the sword results in a straight sword becoming curved after the final quench. This might explain why the cut surface of the star became convex, while the rim (all martensite) remained straight.

Tekkotsu on this tsuba? I don’t think so, but I’ll leave you to judge. I have a tosho tsuba with tekkotsu, about 2mm by 1 mm, popping out of the iron like dinosaur bones from a rock face. These, if tekkotsu, are small, but I’ve seen tsuba for sale with similar irregularities described as tekkotsu (everyone seems to love a pile of old bones). What I also like about this tsuba are tiny bright specks scattered about the surface, in the central part, inner and outer rim. I think these are fragments of hard iron (martensite), less than 1 mm in size, which have either failed to take up the patina, or have had it rubbed off over the years. I’ve never seen this before, but I suppose they could be considered as small tekkotsu. I think I have managed to capture the feature in the attached photos. Some are bright and look like iron, but some look like tiny grains of sand imbedded in the iron. The Nihon To Koza, VI, p50 states that ‘speckles’ are common in Kanayama tsuba due to the yakite finish and these specks could easily be described as such. Kanayama tsuba tend to be small and often have heavy rims, but I gather that early ones often have quite delicate and fancy rims, so I’m reasonably happy with my assignment. But please feel free to challenge and comment on any of my observations.

Best regards, John

(just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)

Photos: #33 Tsuba side 1

#35 Tsuba side 2

#37 Pitted (burnt?) rim

#38 stubs of bars, speckle (to right) and concave surface of edge

#80 speckle below nagako ana

#89 Edge of kogai ana, showing narrow rim, indicating that a drift was used to shape the opening. Can you also spot the speckles?

#61 my fire iron showing burnt steel and tekkotsu (not really)

-

1

1

-

-

Hi Ford,

Thanks for the interesting discussion. I've learnt a lot. Yep, theres dearth of good info out there. Looking forward to the book. Love the soft metal tsuba videos. Lots of videos on swordmaking, but I can't find any on forging iron sukashi tsuba, my latest quest. Another opening for you?

best regards, John

-

1

1

-

?chika Signature On Tsuba

in Translation Assistance

Posted

Thanks Steven and Steve

When I read the first reply I was a bit dubious of the first kanji being ‘yasu’ (安) as it looked nothing like my ‘yasu’. Searching on the web I found a couple of tsuba (pics attached) which were sold at Bonhams.

Tsuba 1: Nara Yasuchika II is a similar style to mine, iron carved with chidori, but the signature is安親.Lot 1086, Arts of the Samurai, 08 Oct 2013, New York.

Tsuba 2: A shibuichi tsuba with an with an elephant and sparrows in takabori, shishiai-bori, and copper and gold takazogan. Apparently the tsuba was made to deliberately look worn with age. The signature on this is康親 in a seal, with the two kanji looking like mine. The tsuba was actually catalogued as Shonai, after Yasuchika. Lot 306, Arts of the Samurai, 30 Oct 2017, New York.

So I guess that’s it. Yasuchika. Which just leaves the question ‘Is it genuine?’ Always a problem

Thanks again, help from guys like you is what makes NMB so great.

John

(just a guy making observations, asking questions, trying to learn)