-

Posts

124 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

2

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Arthur G

-

Ah, Inaba Yoshimichi was the wearer! Haruta Mitsusada the smith (well, for the kabuto at least). He's not of particular note historically, but his armor certainly is. https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/稲葉良通

-

The Transitional Mogami-dou and the Nuinobe-dou The Mogami-dou went through some refinements in the 1580's. We see the muna-ita become clipped at the top, creating a flatter profile. The waki-ita developed more elegant and rounded shapes, often with a mountain shape in the middle below the armpit. This did exist in the preceding decades but is far less common than what we see in the 1580's. A built up and striated surface pattern is created with lacquer quite commonly in this period as well. Here is a great example of what my group refers to as a "transitional" mogami-dou. Note the iyozane kusazuri as well. There are many other fascinating features of this armor, but I am going to keep this thread focussed. Especially worthy of note is the overall shape of the armor. While it is still a go-maiedou, we are seeing the beginnings of a more rounded shape forming. At this time we also see the Nuinobe-dou soaring in popularity. This example is of particular note. Gifted from Toyotomi Hideyoshi to Date Masamune in 1587, we are now truly seeing the beginnings of the round shape people are so familiar with. However it seems many nuinobe-dou well into the 1590's were still of a go-mai-dou construction. Mori Takamasa's armor used in the second invasion of Korea is a great example of this. However, there is something quite modern here that is very important to note. We can clearly now see the later style of Muna-ita and Waki-ita, and can firmly place it in the 1590's. Finally, all of the ingredients are there for the modern Okegawa Nimai-dou. All it takes is the right person to combine everything together...

-

The Riveted Kanto Dou While other regions were adopting the mogami-dou, smiths in the Kanto region quickly began advancing the design. Seeing as the mogami-dou was already a tachi-dou, why not rivet it together? Tachi-dou are not only held together with the odoshi we see on the surface. Underneath, there are separate holes drilled for tomegawa, a sinew lace that keeps the plates from slumping down like old armor. As the name implies, the armor stands up on its own. In the Kanto region, some of these smiths used leather lacing lacquered over to bind the plates together while others used rivets. Here is a riveted example that seems to have been converted over from a sugake laced Mogami-dou. The lacing holes appear to have been filled in. Note the top lames of the kusazuri have survived, being made out of metal, whereas the missing lower lames and the right and rear sets are completely missing; it is more than likely they were leather. From here we can see exactly how the Yukinoshita-dou evolved. Yukinoshita Denshichirou Hisaie created his infamous design as early as 1573 by some estimations, but it wouldn't be truly adopted en masse until the early 1580's when the Date clan found themselves quite enamoured with the design. When comparing it to the riveted Kanto Dou, it's an obvious step in the design evolution. Rather than using multiple plates riveted together to form the body, single large plates are used. Once again however, we do not see any drastic changes to the overall geometry of the suit. The Muna-ita and Waki-ita are still the same old shape, and the overall construction is a gomai-do. We are still nowhere near the Okegawa Nimai-dou.

-

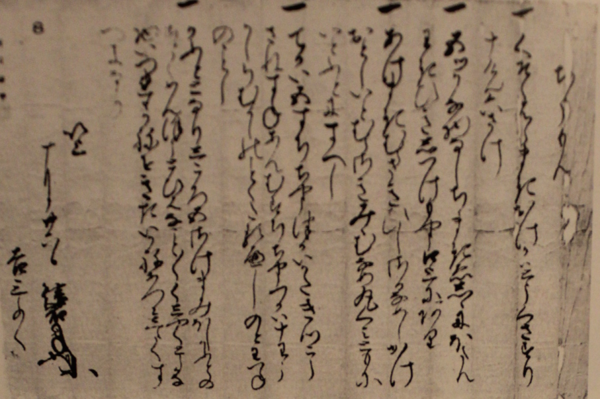

The Mogami-Dou: Part 2 The earliest reference I have ever seen to the Mogami-dou is likely this armor order from the early 1570's. In it, an "Okegaha-dou" is specified. All evidence points to the Kin-dou and the Mogami-dou being developments in Eastern Japan, likely around the Kanto Region. However, the concept spread across the country over the next decade or so. Inaba Yoshimichi's armor is a wonderful example. Made likely in Nara or elsewhere in the Kansai region, we know it was used towards the latter part of the Ishiyama Honganji War in the late 1570's. In it we see an interesting hybrid construction of both plates and kozane. The example at the Royal Armouries was gifted from Satsuma to a foreign power in the early 1580's if I recall correctly. This means we know the design had made it down to the farthest Southern end of Japan by this time. However, even by this very late date, we are quite far away from the popular image of Ashigaru all running around all clad in riveted Okegawa Nimai-dou. If this was the highest grade gear for samurai at this time, then clearly there is something very, very wrong with our image of this time. There are still quite a few more steps to get to that design, and we will see when it likely first showed up on the battlefield afterwards.

-

The Mogami-Dou: Part 1 The next stage in development followed quite quickly after the kindou, and in reality was not as big of a leap in design as it would seem. For all intents and purposes, the Mogami-dou is a kindou that uses solid sheets instead of sane. It must be kept in mind that sane are not separate elements, but rather laced and lacquered into solid boards. Making one of these solid boards out of one piece of steel rather than a few dozen scales was a logical step. And if the industry was there to make it possible, so much the better. When we look at the early Mogami-dou, this is in reality the only appreciable difference. The muna-ita, waki-ita, watagami, etc. are the all the same. The construction is still a boxy go-mai-dou. This becomes even more apparent when we see Kebiki laced examples. I find myself having to look very closely at these to confirm they are not in fact made of kozane. Keep in mind these would have been very, very expensive armor at the time; this would have been truly cutting edge equipment. Interestingly, it seems a cheaper form was developed for lower ranking troops. Unfortunately, the gear of the common masses rarely if ever survives from this time, skewing our views of the era considerably. When one only sees the highest grade of gear, they tend to push that image towards being the norm, rather than the exception it would have been. Here is that downgraded form. Miraculously, one example has survived to the present day. This is an all leather Mogami-dou. Note the two prior examples are of domaru construction, while this is a haramaki. Mogami-dou were made in both forms as well as both Sugake and Kebiki odoshi.

-

The Kindou: The First Stage of Evolution From the Asuka period to the advent of Ko-tousei armor, Japanese cuirass construction is made up more or less unilaterally of sane in one form or another. In the Kofun period we see the Tanko and the Keiko, with the Tanko line of evolution dying out in favor of Keiko. This over time evolves into the "domaru" and "Oyoroi" of the Heian period, with domaru being quite well adapted for fighting on foot and the Oyoroi making a horse mounted archer into something relatively comparable to a modern day armored gunship. In the Nambokucho era, we see the death of the Oyoroi line of armor evolution, with the Domaru/Haramaki completely taking over. The conditions of the Nambokucho wars and changes in doctrine are what caused the death of such magnificent suits. Much of the war was fought in locations that were not conducive to cavalry, primarily hilltop forts. Horses in this time more and more became relegated to a means of transportation to a battlefield rather than something to be utilized upon it. The Oyoroi we see still being used was more and more modified for usage on foot, but in this regard it fell short in terms of practicality against the domaru and haramaki placing the weight upon the shoulders of the wearer and not being tightly fitted to the body. The form that the domaru and haramaki would take at this time would remain more or less unchanged in terms of construction, with only minor differences appearing over the next two centuries. In terms of materials, the kozane used to make these cuirasses were made up mostly of rawhide, with steel (some would use the word iron, but this is a long side tangent better for another time) being used every other scale in places where the wearer needed extra protection i.e. the chest area and sides. From the Heian era onwards, we see the thickness of kozane, both metal and leather, declining over time. However, lacquer techniques were always developing and becoming more elaborate, with kokuso and sabi-urushi appearing. Iyozane also appear, sometime likely in the 1400's, as an alternative method of producing a piece from scales. Sometime towards the end of the Muromachi-era, we see the development of the Kin-domaru and Kin-haramaki. Visuallly you'd be hard pressed to see any difference from the earlier forms, but on a technical level there is a very, very important difference: In this case, all of the kozane or iyozane in the body area metal, rather than alternating. Hence the name "kin", in this case meaning "metal". As far as I can tell, this development in terms of being something produced in some significant numbers rather than one offs, seems to be in full swing sometime in the 1560's I can say conservatively. Possibly earlier, but without hard evidence for it I am more comfortable with this placement. Firearms usage had begun to proliferate more and more by this time, though not to the scale we'd later see in the 1570's. It's quite likely that if my placement is correct for this development, it is likely a response to this as well as massed spear formation warfare. It's also worth mentioning that the importation of namban-tetsu and the ramping up of localized industries in Japan to keep up with the proliferation of armed forces and escalating conflicts probably made the production of all metal armor far more feasible than it had been in the past. Illustration of a Kin-Kozane Domaru Black Laced Tetsu-Iyozane Haramaki: Note the kusazuri in both cases are still made from leather kozane to reduce weight.

-

I personally think the tatehagi has some relation to the evolution of the hatomune-dou, but I haven't looked into them enough to say much. I mostly avoid Edo period armor, which they fall into.

-

Absolutely! This is an "Okegawa-dou" in its raw, original conceptualization in terms of nomenclature.

-

Introduction I was encouraged by a friend to share some of our research to the general public. When trying to think of a topic to start off with, this was the best one that came to my mind. My particular focus is on the latter half of the 16th Century with the evolution of armor and firearms technology. With the goal in mind of replicating exactly what was used in this era, I found that nearly everything I had ever learned in the past was wrong. The current popular image of arms and armor in this time is so skewed as to lack nearly anything resembling the true reality of the situation. Needless to say this was engrossing, but also disconcerting. The most widely misrepresented piece of armor, bar none, is what is colloquially referred to as the "Okegawa-dou" nowadays. Over time, I have seen its inception pushed farther and farther back in order to authenticate either particular pieces in museums, collections, or images in media. Rather than hold these items to universal standards, the standards are shifted to verify them, which is quite backwards. Here I will demonstrate a clear and concise evolution of the armor from a technological standpoint, why it developed, as well as how and why the nomenclature has changed over time. Nomenclature and Etymology The origin of the name Okegawa-dou is the first thing to address. Unfortunately, the sense of the name has been misinterpreted in the Western-sphere quite egregiously. Unilaterally it seems to get translated as "tub-sided"; to the English speaking mind, this evokes a rotund image. Due to the shape of the much later Okegawa-nimai-dou, it seems to confirm this notion to many. Unfortunately, this is not what the name is referencing. There is a deeply engrained tendency for Westerners to base their descriptions and appraisal of Japanese items on what it looks like to their eye. This leads to a fixation on things of a decorative nature, or a deeper need to relate something truly foreign to something more familiar from their own culture. This is what the word Oke is actually describing: It is not referring to the appearance of the object but rather its construction! This is the case for many (thought not all) old styles of Japanese armor. The old fashioned Japanese tubs and buckets are made with wood slats tightly butted to each other. So, a "tub sided" dou is referring to the construction being like that of the sides of a wooden bucket or tub, being made of flat plates of steel. But where and when did this term originate you might ask? This will be addressed later after showing the physical evolution of the riveted plate, two section Okegawa-dou. For now though, in short, this term was originally used to describe what we now call the Mogami-dou, and was already in use no later than around 1570.

-

There's a very simple truth to be gleaned from this one. The very fact there is almost nothing to say about is everything. When someone takes an original helmet to use as a base for a hobbyist level project like this, it ceases to be a kabuto. There is nothing to remark upon because there's nothing of value left. To put it quite simply, there is nothing being created; only destroyed. This is nothing but erasure of Japanese material culture.

-

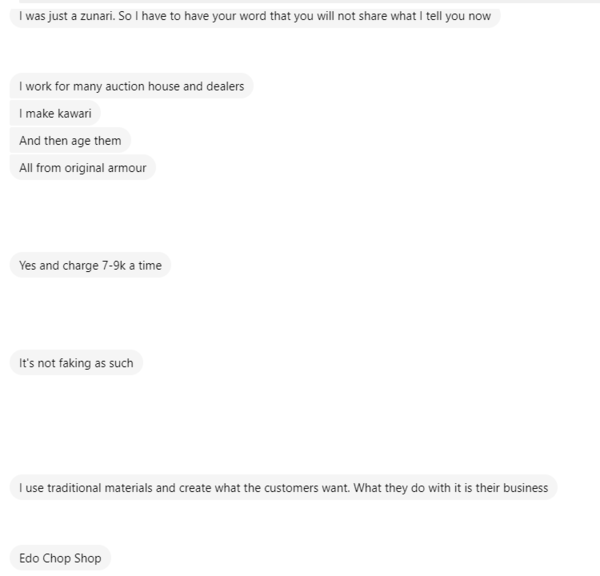

Now that the conversation is in full tilt, I think it's the right time for this. I don't think there's really much I need to say. They say it all themselves quite succinctly: There's another example that's circulated around in the community that I think will be much easier to assess now with this in mind.

-

Well, he/she/they have no ability to make a helmet from scratch, which I have confirmed from numerous internal sources now. So he/she/they relies on either replicas or in most cases damaged originals as a base for... should we say "creative expression"? Hence the "it's not faking as such"... but just an advanced restoration

-

I think Chris would be the man for the job on that one!

-

Ohhhh it's a complete redo! Gotta tease everyone just a little bit more, so here's another snippet. But let's build up a nice little base of examples first before I serve up the entree.

-

This will be a general thread for posting known and suspected fakes produced currently in Europe. A surprising number have appeared in the market over the years, which all seem to be coming from one source. There are certain identifiers that become glaringly obvious once you've seen enough of them. Now that this forum has access to two actual armorers, the members here will have access to unbiased technical knowledge and analysis of these, making it easier to spot and purge them from the marketplace. I have some info and examples I've gathered over the years that I'm very much looking forward to sharing with the community. However, I'd like to see everyone here sharing some they've encountered themselves rather than have me direct the narrative; afterall, there is a long, long list of people that have been affected in some way or another. Please don't be shy! And if there are any that you are unsure of and would like a second pair of eyes on, we would be happy to help. The focus of this faker is on kawari kabuto in particular, needless to say, but he/she does have quite a range of things they like to trash. Over the years I have gathered a shocking number of sources on their practices, all of which having told consistent yet separate stories. I must say, the portfolio is quite extensive at this point! Funnily enough, I had no interest in this person until they decided to make it my problem a few years ago. All I wanted to do was make my armor and matchlocks, as I always had from the beginning. But they just couldn't leave well enough alone could they? Just so involved parties know that I mean business, here is a sampler.

-

I'd be very eager to see it! If I do go for it and go through the misery of hand filing 2000 rivets, I think I know which one I'd want to do for this. Without any doubt, it'd be a Bamen. Been going down a rabbit hole with them today and I'm utterly fascinated. Not to mention I'm seeing some very very possible Saika influence in them.

-

Well, I won't be testing them while wearing them I would like to use a ballistic gel head, and maybe something that can measure the force imparted to the wearer. It's not enough to stop a bullet from penetrating; you also need to dissipate the energy being transferred to the person under the armor. For that reason it's not enough to make a test plate or a bowl; I'll have to make something with a complete shikoro. As far as that theory goes, I'd never heard of it until joining the JAS. I found it quite interesting, but I have some doubts. Personally, I don't think it was to stop solid shot, but rather to mitigate the damage from "sennin-goroshi" (basically shotgun pellets). And that's correct with the laminated steel! However there is no iron used. The inner layer is a low carbon mild steel.

-

Have some things planned in regards to ballistics testing different designs against different calibers in the future, absolutely! One of the top ones on the list is testing the theory that the koboshi kabuto was developed in response to firearms. I'm also going to be working on a 2mm thick Laminated steel okitenugui down the road. I'm not sure if anyone has actually forged out these types of plates in quite some time. I found the method for doing it in an old book, so hopefully I can pull it off!

-

Oh absolutely John. In fact with my teppoutai I'm building up, I'm actively encouraging that with everyone with their gear as they get it together. Do not do cookie cutter matching gear under any circumstances, unless it's a particular Edo period group with all matching stuff. If you're doing Sengoku/Momoyama, nobody in the group should match each other, let alone individual components of your kit

-

Oh they're a nightmare. My hands were so raw after making yours it's not even funny. Each one of them probably took at least half an hour to 40 minutes, and that was after I figured out the method and got faster at it I didn't want to tell you how bad it was haha That's not including the za.

-

This really is an incredible write up Chris. I've seen you refine it over the last year or so and it's just excellent. I honestly think it's not a bad price guide to work off of actually on my end. In regards to the compliments on my work there, all of you are far too kind. I'm not good at receiving praise, as I'm not used to it I hope the finished form of it still gets the same reaction. It might be a bit jarringly different when the shikoro and some other accoutrements are there. That document you shared there is also incredible Gakusee. Things like this are very rare to see. My team with reviving Tsuda-ryu found a fantastic document outlining a matchlock order for Jiyusai-ryu. We gleaned a lot of invaluable information from it.

-

Another issue I think that is very important to bring up is that it's often no longer thought of as armor! One of the things that I have focused on a lot is the practical side of everything I'm making. Because I am sizing everything to be worn by my modern customer, I might as well make it protect their noggin A lot of the modern factory armor is lacking in a huge amount of ways in regards to the protective qualities of the original stuff. There's a reason armor is cold hardened with a hammer in the Japanese style and not pressed. Rivets have a lot of very important functions, and welds don't don't work the same way. Then there is a ton of stuff going on with the geometry of these.... Urushi as well has multiple functions, and even the lacing. Kuteuchi produces a structure in the lace not present in machine woven lace which prevents it from unravelling if some of the strands are cut. So in those days, we're not of course just buying something for looks, but in essence you are buying something to keep you alive. Spending that amount of money to keep yourself from getting gibbed seems like a decent investment even in light of the relative cost. There are many layers to the added value of it when you really think about it. For example, you could even look at the impact it'd have on localized economies if too many of their men didn't come home from a war. The overall rice tax yield would decline proportionally I'd imagine; armoring your local conscripts might have a lot of different economic angles to it as well worth pondering.

-

Thank you Brian. I for one appreciate being allowed in here as a guest more than you know. I will try and keep what I say on a very technical and factual level, as there's no room for drama, emotion or hyperbole here. There are some severely concerning things going on behind the scenes that I think will truly shock some people once we get to that point in the conversation; I will also post some of my ways of spotting these poor restorations (and fakes), where I've seen them appear, and maybe even some case examples. Chris' example is one of the best I've seen. Japan is my adopted culture, and I owe it to protect the material history and past of that culture through my studies and work. Poor restoration work and creating forgeries does not just hurt people's wallets or individual items; it slowly shifts people's perceptions of the past and the nature of these objects towards something they were never meant to be. It has a wider impact over time of warping cultural heritage. Further, is not a matter of tastes or opinions as some might argue here; there is the right way, and there is the wrong way. Either it has been restored to its original condition as close as is possible, or it has not. Having a space to address this is much appreciated.