-

Posts

95 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

1

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Emil

-

-

That's a good point that I actually didn't consider However, it doesn't really explain the inconsistency in the labeling of these linked blades, as all of them (incl. mine) are almost exactly 70cm in lenght, with varying sori depth.

-

This is helpful, thank you for the input

-

This might be a very trival matter to discuss but I'm genuinely confused by the descriptions of sori for these blades from the same dealer My blade is described as: Sori: 1 cm - "deep sori" Other blades on their website: Sori: 1 cm - "small sori" - Kamakura Sori: 1.1 cm - "moderate sori" - Meiji Sori: 1.2 cm - "slightly deep curvature" - Kamakura Sori: 1.4 cm - "deep sori" - Nanbokucho period Sori: 1.7 cm - "deep curvature" - Edo Sori: 1.76 cm - "somewhat deep curvature" - Edo Sori: 1.9 cm - "little deep curvature" - Edo Sori: 1.97 cm - "deep curvature" - Muromachi Sori: 2.8 cm - "deep curvature" - Contemporary Is it just random,or is in relationship to the era/ school or the sword? While we are on the topic I also have my blade hada described as "Koitamehada is grained well, looks like plain" - how can it be plain (muji?) and well grained koitamehada at the same time? Also the hamon is described as niedeki but looks like nioi to me

-

What’s your go to sword oil?

Emil replied to Cookie_Monstah47's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Interesting instructions from Aoi Art: "Generally, Choji oil has been used to treat Japanese swords. This is a sticky vegetable oil traditionally used in cleaning swords. It promotes oxidization of the blade that will result in rust in the future. In our opinion, and based on our experience, we do not advise you to use Chyoji oil. We suggest that you use high-quality machine oil on your sword. This is the same type used when maintaining guns or sewing machines, and it is the only oil that we use with our swords at Aoi Art." The only problem with this advice is that there are so many different kind of oils out there, and other people warned that the wrong oil could cause oxidation. In the end it's not clear to me what oil is optimal -

I wish it was! The blade I held was one that one of his apprentices was working on, an early Edo era sword. The other one Hitoaki was working on we didn't talk about, but I'm assuming it's a very expensive one. With so much demand for his skills, he needs to draw the line somewhere, so he only works with the finer swords. One funny thing I forgot to mention. I asked one of the apprentices why he started learning this art. He said it's because he is a martial arts teacher, in iaito, battojutsu, etc. and it's a good extension of his business to be able to provide polishing for his students. He went on to explain that he uses a Muromachi era katana for cutting. Which I mentioned would never be done in Europe or USA. It was the first time he heard that the Chinese make fully working shinken for as low as 120 USD, they were laughing and couldn't believe it. I went on to show them some pictures of ryansword which they were not impressed by, other than the low price. Later on we went to the club and tried some tameshigiri cutting with that Muromachi katana. It was very beat up and slightly bent halfway down the blade. It was still a cool feeling to cut with a 500-600 year old katana. And the coolest part was probably to meet their grandmaster, in his 80s, he's a descendant from a long line of Samurai who has passed the swords skills down, dating all the way back to the Edo period.

-

I had the pleasure of meeting Manazu Hitoaki today and watching him work in his home in Osaka. It was a fascinating experience that significantly deepened my understanding of the sword polishing process. Despite his immense skill, he is very humble and spoke only a little English. Fortunately, his apprentices were more than happy to translate and quickly mentioned that he is one of the finest sword polishers in Japan. Some interesting facts stood out during the visit: Hitoaki learned the art of polishing from his father at the age of 15 and has been improving his craft for 58 years. Hundreds, if not thousands, of blades have passed through his hands. Currently, the demand for his services is so high that customers face a two-year wait. He works diligently, more than 10 hours a day, to complete each sword on time. His rate is 20,000 JPY per sun (1.3 inches/3 cm). One of his apprentices eagerly explained the process and the stones used. He has been training under Hitoaki for eight years but still considers himself a beginner. He mentioned that he wouldn't charge more than 8,000 JPY for the same polish as his master. As an amateur knife sharpener myself, I was curious about how they maintain the niku of the blade during polishing. They explained that they work on a very narrow section of the blade at a time, gradually transitioning down the convex surface toward the edge in small increments. Each section is completed before moving on, rather than working in long sweeping motions. Their ability to assess a blade with such precision is astounding. The apprentice handed me a blade and asked me to hold it to the light, pointing out that it was uneven. Despite my best efforts, I couldn't see any imperfections. It really highlights the incredible attention to detail required in this craft. Much of their skill is visual; they don’t count their strokes on the stone but continuously check the blade until they are satisfied with the result. It’s quite remarkable. Hitoaki shared that, despite his best efforts, he has never delivered a sword with a perfect polish, there’s always something he feels could have been improved. He also mentioned that, though the old grandmasters are long gone, he continues to learn from them by studying the swords they polished. This is a vital part of his work, as he strives to adapt his polish to each blade, taking into account its era and style. If the current polish is good, he aims to replicate it in the same way. A very interesting experience that I won't forget.

- 7 replies

-

- 18

-

-

-

-

This was very helpful, thank you for the explanation

-

I feel like I've overlooked an unspoken understanding, thanks for letting me know 👍

-

Prof Ohmura just replied to my email about his view on Japanese steel used in katanas. Read the translation below: "Mr. Emil, That is a very difficult question. The methods of making swords and the materials used vary greatly from era to era, and there are also differences in the skill levels of swordsmiths. Therefore, I think it's dangerous to strictly compare the differences between periods. However, if we roughly look at the trends, there are a few perspectives: 1. One view is that old swords (kotō) (best) > new swords (shintō) > modern swords (art swords). 2. Blade structure (construction): The mixing of hard and soft steel (steel with uneven carbon content, common in the old sword period) -> The sanmai structure where hard steel is enveloped by soft steel, seen in new swords, newer swords (shinshintō), and modern swords. Even among newer swords (shinshintō) and modern swords, there are strong swords made from mixed hard and soft steel materials. Examples include newer swords (Mito Clan, Katsumura Tokukatsu) and modern swords (Kobayashi Yasuhiro), among others. 3. Materials used: Spring steel (best) > alloy steel > army sword steel > hydrogen-reduced steel > Japanese steel (wakō) In addition, there are also strong swords made by the American company Cold Steel using regular carbon steel. It seems that the secret lies in the sword-making method, including the quenching process. Even swords with the sanmai structure seen after the new sword period are stronger than new swords when it comes to Mantetsu swords. This is likely due to the iron from Manchuria and the sword-making methods used. Given the complexity of these various factors, it is difficult to simply rank the quality based on the period or the materials used. However, one thing that can be said is that the swords from the Edo period, which became decorative swords for samurai, and the modern swords that followed them are the worst as weapons. At the very least, the serious military swords made before the war were better than those."

-

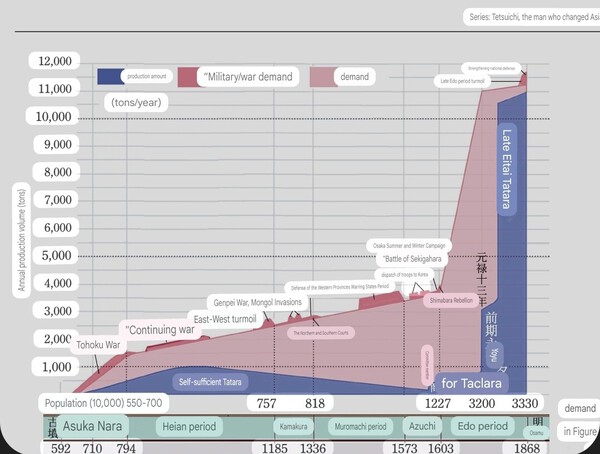

Correct, in the Japanese research paper I shared "Is the material of Japanese Swords really tamahagane" the conclusion is that foreign steel has always been used to make Japanese swords due to limited domestic supply of tatara. It doesn't mean tamahagane wasn't used earlier, but it was not the primary source of steel for most of the history. Here is the conclusion part of the reasarch paper translated: "Tatara steel production was not solely for making Japanese swords. It also met the demands for agricultural tools, construction materials, household goods, and weapons. However, the production of domestically made steel was very limited, and the majority of the demand was met by imported iron. Domestically produced iron (pig iron and tamahagane) only dominated the domestic iron market for a short period at the end of the Edo period. The history of Japanese swords came to an end with the 1876 edict banning the wearing of swords (Haitōrei). After that, the appreciation of Japanese swords became a topic discussed mainly by enthusiasts who regretted the decline of swords. Additionally, in the post-Meiji era, with the rise of nationalist sentiments, the narrative that Japanese swords were made from tamahagane emerged. This trend has persisted to the present day. The truth is that during the late Edo period, it wasn't because tamahagane was superior that it was used for making Japanese swords, but rather because most of the steel available at the time was inevitably domestic Japanese steel. Out of the 1,000-year history of Japanese swords, tamahagane was primarily used for about 70 years during the late Edo period."

-

I know it's kinda odd, right? These accessories take time and money to make Not only that, it came with a full lenght tsunagi and a pristine uchigatana koshirae and what appears to be a decent polish. I guess I paid for it all, since the price was 350,000 JPY. Correct me if I'm wrong, but that's quite high for a Showa-to?

-

Thanks for the pointers, I will save those and take better photos when I have the katana

-

-

You're probably the fourth person saying this. Maybe it's just the pictures. Since I bought it as a Showa-to I was certain people here would say it's a school book example of an oil quenched blade. But so far nobody has said that. Makes me wonder if I need to challange the assumption of it being a Showa-to

-

-

Unfortunately, I don't at the moment, not for another 7 weeks at least. It's with my brother who can't be of any help in this. But really helpful illustration, I'll save that one, thank you!

-

I finally have som better pictures of my Showa-to. I've tried my best to look at references pictures but I can't come to any conclusion. Anyone out there who can tell me if it's oil quenched?

-

How available was tamahagane?

Emil replied to Ken-Hawaii's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

This can be read in English with the help of chatgtp. I've corresponded some with Mr Ohmura from http://ohmura-study.net/003.html on this topic. Interestingly enough, tamahagane is according to him and the research he quotes an exception rather than the rule in Japanese sword making. Japan has never had enough domestic supply of sword steel to make all the katans needed. Most of time, especially during the production of Koto the steel actually came from China or Korea. I know this is quite a contradiction to the popular belief, so I recommend that you read the article. / Emil -

Adding another article on the topic, use ChatGTP for translation. In short, Japanese swords were made of tamahagane mostly in the later years and during Edo. Earlier, imported steel from China and Korea was used to make katanas in Japan. This is part of a wider topic that Noriyuki Omura is advocating on his website. Who I had the pleasure of exchanging emails with. See: http://ohmura-study.net/003.html His main thesis is that the Japanese sword community is snobbishly discriminsting Showa-to from being considered Nihonto, on false grounds. Japanese swords were never exclusively made of tamahagane and the process of making a sword was never unified anyway. All sorts of methods and steels have been used throughout history and by different smiths at the same time. Special ordered or Koto massproductions, they are all considered Nihonto. The evolution of the forging process took place in parallelly inside the country for centuries, but the last evolution which led to the revival of Japanese swords and possibly saved the art form is neglected. Mainly due to politics and lack of historical knowledge, the current legal definition of Nihonto is restricted to the very narrow Edo style production methods of both the steel and forging, which unfortunately excludes Showa-to. His father laid down his life in the last stand, defending Japan from the American occupation. He asks why the same respect is not granted that sword, which was carried by the modern Japanese warrior. He claims despite the Japanese sword community's attempt to discredit the Showa-to, many of them were better suited as weapons than Edo period swords which could be too brittle due to overemphasized focus on esthetics, which led to too wide hamon, etc. Especially Manchurian and Spring steel forged swords had an excellent reputation for their quality and durability in combat. I like this quote by Mr Omura: "as a result of the occupation policy, the art sword world has made the purpose of Japanese swords the beauty of the blade. This has led to a misunderstanding of traditional Japanese swords. As a result, the irrational notion that military swords made of superior steel are not Japanese swords has spread throughout the world. This is a big mistake." 再校刷-2.pdf

-

As a beginner in this vast field of Japanese swords, I'm learning more and more every day. I just finished reading The Connoisseur's Book of Japanese Swords today. In the book I came across the term "Mitsukado", also reffered to as "Mitsugashira" which is described as the point which the yokote, shinogi and ko-shinogi meet. It's said to be a critical area where the sword smith can showcase his skill, or expose his lack of skill. There were no examples provided of what this looks like in practice. Can someone please give me some examples or points to look for? What distinguishes a good mitsukado from a bad one? / Emil

-

In the end I think it makes for a good match, I don't regret it. Although I must admit I don't have a refined taste in this. A great gift to my father who is not a collector nor does he have any particular knowledge on the area. It is the intended gift katana you see in the picture, a WW2 Showato in uchigatana koshirae and shirasaya, even came with full lenght tsunagi. Well forged, but not something to write home about. At least I can present the sword as bought and made in Japan, and 100x better than giving him a chinese made MiniKatana, IMO. And I'm sure you all agree, rookies like us (me and my dad) shouldn't be handling the most precious swords out there 😉

-

Yes it's all from the same dealer, with both my tsubas on the far right and left sides of the table. I'm sure the other tsubas (see this picture) might be "better" but they didn't appeal to my untrained eye in the same way. On another note, these three were the suggestions of the dealer, while the forth one that I actaully choose, was my pick from the iPad they gave me to sort through their vast selection. You can see the prices here as well 45-50k Yen

-

Jake, you're so right, Li Naomasa family crest, Japanese maple leaf, spot on. Regarding the material, I'm not sure. I agree, being a Showa-to it's the kind of tsuba that fits the sword. I was choosing between a lot of tsubas and this one just spoke to me. Thank you all for providing me with more knowledge

-

Interesting observations, I will examine it more in detail when I get back home