Rolland

Members-

Posts

11 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Rolland

-

You're right, of course. I looked at Jan Pattersson's book on Yonezawa Matchlocks. Although the less-than-ideal illustrations are the Achilles' heel of this otherwise wonderful and fascinating publication, they clearly show that the Yonezawa teppo's did not have the hinawa toushi ana , nor did the related Seki-ryu style matchlocks.

-

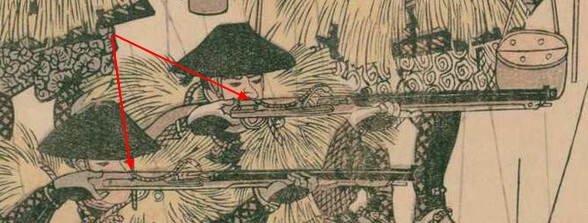

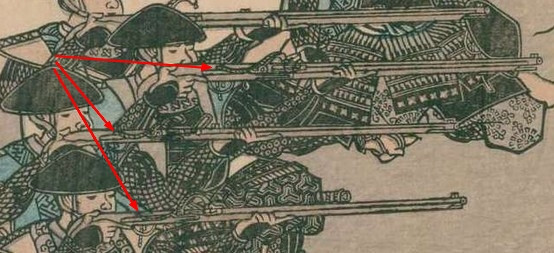

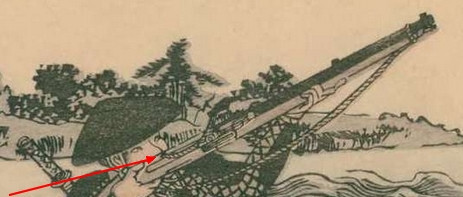

Piers, Thank you for the interesting information about shields. It seems that this book by Masatomi Ōmori/Utagawa Kuniyoshi was the source of illustrations for many other publications, including books by Perrin and Turnbull. I just bought an electronic publication on Amazon (for ~$3) that is apparently an excerpt from the aforementioned book. Its main themes include teppo gumi crossing water obstacles, artillery and the use of teppo from horseback. These are simple graphic scans without underlaying OCR text. The text on the illustrations is also scripted, so using an external OCR tool might not yield useful results. The text is therefore useless to me, but most of the publication are illustrations, and they are fascinating and of goof quality. I've seen some somewhere, but most are new to me. I particularly like the image of a samurai using a horse's head as a gun support. If the horse was calm, it might work well, but I doubt the horse liked it ... Numerous images show soldiers firing teppo. In most, it is clear that the hinawa is threaded through the hinawa toushi ana:

-

Piers, Thank you so much. As always, you've opened my eyes to many things. In particular, I understand that there wasn't a universally accepted teppo drill, and different centers may have developed different routines. I did some research on the illustration I used, and it doesn't look as period as I thought. It seems to be from a book on martial arts published in 1855: 武道芸術秘伝図會 初編, by Masatomi Ōmori and Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Judging by the "pavises" (Tate - 楯- is that the right term?) this could be a siege where ashigaru hidden behind shields try to suppress the defenders on the walls. The hands are of course reversed, but I assume it's a mistake by the artist, who was not a soldier. Nevertheless, I still assume that loading from hayago required the use of both hands. I was intrigued by the mention of the hinawa-ire - it reminds me of European grenadiers who wore a similar device. Congratulations, being a practicing "historical shooter" myself, I have great respect for people who have acquired personal knowledge in this way that cannot be read in books or watched on YouTube.

-

Since acquiring my first tanegashima two years ago, I've demonstrated it many times - mostly at shooting ranges. The interest was high because no one present had ever seen anything like it up close. The cheekpiece buttstock, in particular, is almost unknown to Europeans. My teppo was in shooting condition, so I usually ended with a target shot at 25 meters. Light charge of slow powder (20 gr 1.5 FG) and a 0.5" lead ball on a thick patch provided a great show. In the next step, I wanted to realistically show how the teppo was operated in battle - the full cycle from firing to reloading. I've done this already with the arquebus, but there are detailed descriptions, for example, by Jacob de Gheyn or the Spanish. I assume, however, that the Japanese teppo routine was different, if only because of the way of handling the lit match, which is critical. When loading, European arquebusiers and musketeers held their guns with their left hand, away from both the breech and the muzzle. A slow match, lit at both ends, was held between the fingers of the left hand. The right hand was sufficient for other tasks, whether loading from a powder flask, „apostles”, or paper cartridges. However, Japanese soldiers who loaded from hayago, required both hands at the muzzle. Historical illustrations confirm this. What was happening to the lit hinawa at that time? I can't imagine that while charging, the still lit hinawa was stuck in the hibasami? Another mystery to me is hinawa toushi ana. The hinawa was threaded through it but what happened during charging? If the hinawa was removed with the hibasami, did it swing freely with the end lit, or was it pulled back through the hinawa toushi ana with only the short end sticking out? I tried to find the answer by watching a lot of Japanese reenactment videos on YouTube. I never noticed the hinawa passing through the hinawa toushi ana, and the shooters always held the hinawa in their left hand in the "European" manner. This makes sense, as reenactment is about maximum safety, but I think it does not correspond to historical reality. Some authors believe that a soldier could be taught to fire a matchlock in a few hours. I find this very doubtful as it's an unforgiving weapon. To be useful on the battlefield without harming himself or his comrades, the soldier had to master the entire procedure to blind automatism. This can only be achieved through (at least) many weeks of hard training. Furthermore, the entire unit had to be trained uniformly, ensuring everyone operated at the same pace and without interfering with one another. So I'm curious if there are any historical drill or training manuals that detail how Japanese soldiers actually operated their teppo in battle?

-

Did the Japanese use patched roundballs in teppo?

Rolland replied to Rolland's topic in Tanegashima / Teppo / Hinawajū

Piers, I'm so sorry I'm only just now responding to your post, as I only just noticed it. I haven't logged in for a while, being involved in other projects. What fascinating material that answers so many questions - including some I didn't ask! Thank you so much! -

Did the Japanese use patched roundballs in teppo?

Rolland replied to Rolland's topic in Tanegashima / Teppo / Hinawajū

Piers, thank you very much for your extensive answer. I assumed they used patches, now I know for sure. This technique may have been discovered independently in many places. Perhaps it was even brought by the Portuguese, who probably knew it. I was fascinated by this phrase: 'manuscript of around 1600 showing inventive use of doubling or cutting or linking lead ball' Wars seem to inspire human invention tremendously. Its fruit is a flood of inventions, although most of them impractical or useless. This has always interested me. Are there any sources of information, usable by a “gaijin” (paper or electronic), on these early gunnery oddities? -

The patched ball, of course, is first associated with a muzzleloading rifle. However, the 'Westerners' (Europeans, Americans) also used it in smoothbore guns. This slowed down loading but noticeably improved accuracy. The use of patched roundballs by light infantry armed with smoothbores (tirailleurs, jägers, etc.) is mentioned in military literature. Everything indicates that it was also used in smoothbores by hunters, as evidenced by archaeological finds. For non-shooters, let me briefly recall the reasons for the inaccuracy of smoothbore weapons. The ball has the so-called wintage, i.e. its diameter is smaller than the caliber of the bore. As a result, while moving in the bore, the bullet randomly hits the bore walls, which gives a double effect. 1. The ball leaves the bore along a line that does not coincide with the bore axis. 2. The ball rotates around an axis transverse to the trajectory, which - due to the Magnus effect - causes a (approximately) parabolic bending of the trajectory (like volleybal topspin). The intensity and vector of both phenomena is random, but their effects add up. The patch virtually eliminates it, not to mention better use of powder gases. If the ball is round enough, it will fly more accurately, especially over a longer distance. Where accuracy was more important than rate of fire, the 'Westerners' could use rifles. The Japanese only had smoothbores, but I suppose they may have been interested in achieving maximum accuracy in many situations. In this case, patched ball would be a simple and even obvious solution. In a pitched battle (close formation, stress, fear, clouds of smoke covering the target) what mattered was the rate of fire and I think that in Japan the situation was no different from Europe. However, during a siege or hunting trip, for example, accuracy could be more important and there was enough time to allow for careful loading. Was Takeda Shingen's wounding at Noda Castle a result of chance or meticulous gun handling? That's why I'm asking if there is any information in Japanese sources, e.g. shooting school manuals, about the use of patched roundballs in teppo? The illustrations suggest that great attention was paid to aiming, but were measures recommended to reduce ball dispersion?

-

Piers, Your explanations satisfy me very much. The age of the weapon was essential because under our law any non-cartridge firearm manufactured before 1885 is free. Although the seller wrote "Edo period" on the invoice, I do not trust the actual competences of European auction houses when it comes to Japanese weapons. The fact that you consider it a "generic weapon for light military use on a battlefield anywhere, a typical Tanegashima-style gun produced throughout the Edo Period" also suits me very well. I was counting on my first teppo to be a demonstrator of typical firearms technology from the Edo period. If so, it turned out to be a good purchase and its exact production date is no more of importance. Thank you very much once again!

-

Piers, I am extremely grateful for such a comprehensive and comprehensive answer. Thank you very much for your time and effort. You shed light on and explained many issues that I had no idea about before. As you can see, your help was necessary because my unskilled eye cannot even distinguish seemingly similar symbols. It is very important to me to confirm that weapons must have actually existed around 1872. Can you make any assumptions about its probable period of production? The advice on darkening silver is very valuable. I have a silver blackening agent in my workshop, so I will try carefully and in small steps to give the silver a patinated appearance. Barry, Thank you very much for your answer, confirming my suspicions about the empty mekugi ana. I am always pleasantly surprised when the most logical solution turns out to be correct one (this never happens to me when dealing with any authorities...)..

-

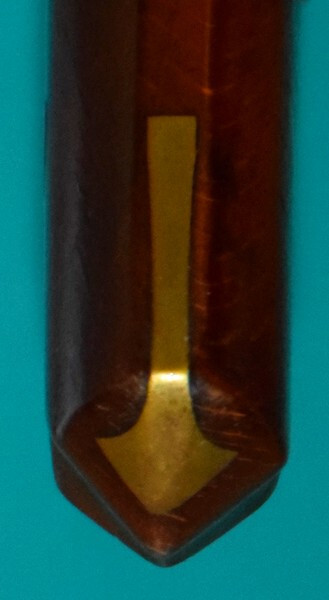

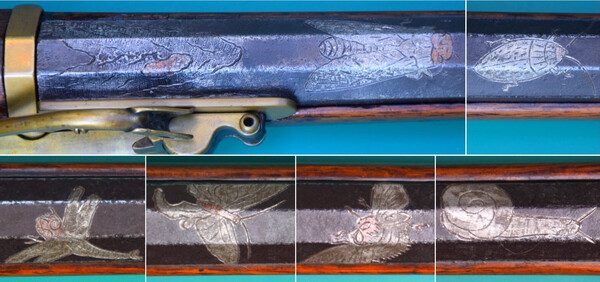

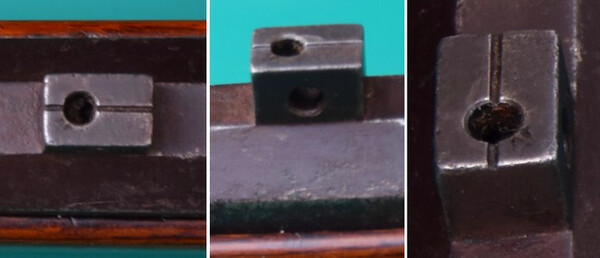

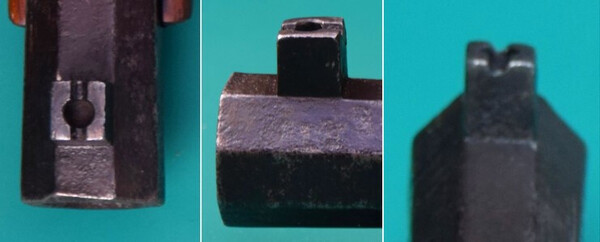

Hello everyone! I'm new here and I'm passionate about history and collecting antique firearms as well as shooting black powder weapons. Collecting antique firearms is not yet popular in my country, knowledge about Japanese guns - minimal and often misleading. I personally for a long time considered Japanese guns to be mere copies of Portuguese arquebuses. However, some time ago, a nice Japanese guy approached me for support regarding Minie rifles. Correspondence with him encouraged me to take a closer look at the Japanese matchlocks. I was very surprised by how different they turned out to be from their European counterparts. I mainly collect European and American breech-loaders and revolvers, but I also love technological curiosities and milestones from different eras (up to percussion). I felt now that without at least one representative teppo my collection would be handicapped. Looking around at various auctions I chose an item that looked modest, almost undecorated, minimalistic and probably that's why it was rather inexpensive (in case of a mishap, I preferred to limit the loss). However, it felt authentic to me, complete, and looked not like a parade weapon but a purely utility gun, which I prefer. My knowledge of Japanese gun is basic - mainly books of Lidin, Perrin, Pettersson, Turnbull, Sugawa excerpts from Internet and especially this extremely competent forum. However, I like to know everything I can about my guns. Therefore, I humbly turn to my esteemed colleagues for help in identifying and an honest, unforgiving assessment, even if the item turned out to be worthless scrap. To get more into the topic, I tried to use Japanese terminology. I prefer learning by doing, but I have no doubt that I have made a lot of mistakes, and I have probably drawn wrong conclusions from my observations. I apologize in advance for abusing the patience of the experts in this way and ask for your understanding for the novice. I'll start with general view and basic information: Total length: 116 cm (45.7") Weight: 3.15 kg (6.94 lb) Caliber: 13,51 mm (0.532") (4 monme?) Bore length: 81 cm (31.9") After receiving the gun, I did what I do with any antique gun. I took it apart, washed it and looked for rust on iron parts (there was some passive rust on the kanime). Here the set of elements and fittings: Wood: The dai was covered with transparent varnish on the entire internal surface and in the barrel channel. This coating roughly resembles shellac varnish, but I highly doubt that Japanese gunmakers used shellac. Does anyone know what varnish was used in Japan to cover the dai? Right-hand side: Left-hand side: The dai shows signs of small unprofessional repair. The split fragment (right side, in front of the hizara) was glued without attempt to fit it or press it properly during gluing. Moreover I detected two thin cracks going from the bisen cavity back to the inside of the dai. To prevent further cracking, I fixed them with a transparent, low-viscosity epoxy resin. Here the shiba-hikigane: All the original mekugi were quite worn and split. The original mekugi went into the bag and I replaced them with fitting pins made of bamboo sticks. The dougane was a bit loose as the dai wood had apparently shrunk. I blocked the dougane by inserting a thin bamboo wedge between dougane and dai. The karuka has a damaged tip, but its length seems to me to be adequate and would be sufficient for loading the weapon. Is karuka the correct term here? Maybe sakujo? What puzzles me is the enigmatic "orphan" mekugi ana on the left side. It is empty and has no counterpart on the right. I've seen something similar in other teppo's photos. I found this mekugi ana very useful for removing the karakuri, but what was its real purpose? Barrel At first glance, the bore of the tsutsu looked tragic, but it was only clogged with a dense, greasy substance. After cleaning, it turned out to be in surprisingly good condition - no active rust, only minor pitting, in any case shootable. In this situation, I considered removing the bisen unnecessary. OK, I tried gentle methods, but as he did not want to move, I gave up. Having experience with unscrewing massive barrel plugs in European muzzleloaders, I had a bad feeling with a supposedly long, thin bisen made of a material with properties unknown to me. So I wiped the bore with a rotating brass brush, treated it with EDTA solution for 3 hours just in case, brushed again, washed it and finally protected with Brunox Lub & Cor. The tsutsu is the only element of the weapon with any decorations. There are 7 engravings on the barrel - all depicting small animals. Shown below individually in order from chamber to muzzle: The engravings are rather rough and finished with (I believe) silver. The red and orange decorations visible in the photos are most likely copper (at least it looks like copper). The juko traces of minor impacts, but they do not distort the barrel crown. The photo below also shows the damaged end of the karuka pushed all the way in: Sights The moto meate looks quite conventional, at least like most similar weapons. Saki meate, on the other hand, is a version that I have rarely seen. Instead of a protruding front sight, it has a groove and an additional hole, as if for attaching an insert. I've seen similar saki meate in photos of other teppo, but very rarely. In his book, Shideo Sugawa in his book shows a similar saki meate with a groove but without a hole in the middle. Here, respectively, the moto meate: and the saki meate: I estimated the relative position of the barrel axis and the sight line. For my purposes, I assumed that the aiming line runs through the bottoms of the grooves in the moto meate and saki meate. It turned out that this aiming line was practically parallel to the bore axis. Gun mechanics: The hibasami was slightly deformed and missed the hizara, but I bend it carefully into the correct position. The hajiki seems a bit flimsy - probably my subjective impression. I am used to the powerful springs of flintlock and percussion firearms. The simple design of the karakuri is illustrated in the photo below: The karakuri works, but I am wondering about something noticed during tests with a simulated hinawa. The hinawa in hibasami reliably hits the centre of hizara, even if it is very short. He would undoubtedly ignite the priming powder. However, this is done only by the inertia of hibasami because it is in a static position the tip of the hibasami is approximately 18 mm (0.71") away from bottom of the hizara. Therefore after the ignition the hinawa is withdrawn from the hizara. This could eventually prevent the hinawa from being extinguished after firing. Is this correct behavior of the hibasami? The problem of match cord extinguishing is known from European weapons. Is himichi the proper term for the touch hole? I estimated touch hole diameter at ~2.0 mm (0.08"). For an obviously heavily used weapon this would be a suspiciously low value. But examining the hizara, on the outer curve, opposite the touch hole, I discovered a thin brass circle. Presumably someone drilled a hole there (maybe conical) and then closed it with a brazed iron plug. The purpose could be to repair the burned-out touch hole by inserting a bushing with a smaller hole there. Were such repairs practiced by gunsmiths in Japan? Signatures: There is an inscription embossed on the left side of the dai: There is (as I was told) registration information from 1872 on the stock: 'Jinshin' and 'Kisarazu Prefecture', where the 'Jinskin' means the 5th year of Meiji (= 1872). In the barrel channel on the dai there is an inscription written (I presume) in ink: On the bottom of the hibuta is (as I was told) the Chinese symbol for 47. At the bottom of the chamber there is - I believe - an identical symbol. Besides, I didn't detect any other mei on the barrel. I have already shown the signature on the inner jiita surface. I found quite similar symbols on the lower mounting surface of the yuojintetsu, on the inner surface of the dougane, on the hikigane and on the hibasami axle: I couldn't find any other mei on the gun. Judging by the caliber, crude ornaments, lack of zagane, simple workmanship, etc. I assume it was not the property of a proud samurai but rather a weapon of lowly ashigaru. Maybe it's a ban-zutsu, unless the 4 monme caliber is too small for a military weapon? Or is it a cheap hunting gun? Above I wrote basically everything I know and what I think (or I think I think). I will be very grateful not only for all specific information but also for every educated guess!