Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 06/18/2022 in all areas

-

A mate asked me to lunch a few days ago for my first visit to his house. Now, I know this bloke well. He has 4 rather nice swords that are above the batting average for a beginner. However, as he was showing me over his old, rambling house that was a once long ago haven for artists of various persuasions, we went down a flight of stairs to a large ground floor room that seemed hardly used apart from a Great Wall of Books. In the gloom on a mantle-piece I saw a kake with a sword on it immediately recognisable by its lack of a drag as a Type 95 I wasn't aware he owned. Having asked permission I picked it up and noticed THE BEST original copper handle I have ever seen. Totally unmolested and with a beautiful, bronze-like patina. No photo sorry as I wasn't prepared. However, I did note that the serial number was 4250. I shall remember it in case it ever becomes available. BaZZa.5 points

-

Tanshu (但州) means Tajima no kuni (但馬国) and its area was the northern part of Hyogo prefecture. Ref. Tajima Province - Wikipedia4 points

-

Very hard to say if this is authentic. The. Photos of the entire blade, or at least of the tip and more close-ups of the blade, could help. I think the signature is trying to say 但州住囗囗 on one side, and then 應永四??on the other. The signature would be Tanshū-jū something, meaning a smith from Tanshū province (present day Hiroshima), but I can't read the characters after that. 應永四 is 1397, but here too I'm not entirely sure of the number or numbers following 應永 . In addition to being cut down, the nakago has been filed kind of crudely, and it looks as if someone has tried to polish the nakago, which has unfortunately stripped it of a lot of its patina, and has made some of the mei illegible. So that, along with the general bad condition of the blade, doesn't make me very optimistic. As always, its best to have an expert examine it in hand.4 points

-

Dear all, I just wanted to thank Bruno for offering some of his pieces to the community here, and to leave a very positive review of my dealing with him. Bruno is a great communicator and a generous individual. Our transaction was extremely smooth, the item was shipped promptly and was packaged very securely, and Bruno included a couple of very thoughtful 'extras' which were completely unexpected, but very much appreciated. Thank you again, Bruno. Regards3 points

-

I’m sure Ford (hi again Ford…long time!) will tell us more but from my experiences in Japanese Meiji metalwork (and as I’m sure you all already know) the Japanese were masters of creating alloys where even the smallest variation in their compositions can create a vast range of different colour nuances when put through the same patination processes. Given that Meiji metalworkers inherited most of their skills and knowledge from sword fitting makers it is reasonable to assume the “soft metal” tsuba etc makers utilised nearly the same variety of alloys. I guess the only way to be sure is to have it analysed by one of those “magic scanner guns” that can accurately measure the metallic element composition. The tsuba under debate could be an alloy that I have often seen called Sentoku. The surface looks as if it may have been created using an etching technique and it may have lost its original patina which causes further confusion! Just my thoughts.3 points

-

3 points

-

Dear Jace. A large shinshinto katana with an o gissaki in nice original mounts, spotted many years ago as I was cycling past an antiques shop I knew. Groaned and pulled over on the basis of, "Well at least I can have a look!" Went in and drew the blade out a little to see a sticker, yes, on the blade, which said £30. Force of habit more than anything else, I asked if there was anything they could do on that and to my surprise the owner said he could do it for £28. With trembling hands I wrote the cheque, knowing that it would make me over drawn, first and last time for that. Next problem was cycling home with it. I still have it, papered now to Inshu Kanesaki. Iron mokko tsuba, gold foiled habaki and seppa, shakudo fuchi kashira and menuki of samurai fighting in boats. All the best.3 points

-

this has nothing in common with anthing Japanese imho. just junk2 points

-

I can't reconcile the brassiness' of the hex tsuba, however the fact that shinchu is copper and zinc and yamagane is arsenous, lead or antimony with copper seems perfectly succinct, as in brass and bronze being different.. John2 points

-

This Tsuba was described as “Yamagané, not Shinchū” (i.e. not brass). Having looked at many examples of 山銅 Yamagané though, they generally seem to be more of a dark reddish brown copper material. There was also 山金 which is to be read Yamakin (although many people read this Yamagané, mistakenly?) Are we aware of these differences in the namings, and what are your thoughts on the material of this hexagonal Wakizashi Tsuba? Seems yellower than brass. Note natural/artificial (?) mottling on surface. Thick, flat, rounded mimi. 7.2 cm x 6.0 cm x 0.45 cm.1 point

-

1 point

-

Mr Dawg (not sure but guess that is your name) hard to say from pictures but if pressed to say then sue koto Mino1 point

-

my guess Kansei time period (not positive on the first kanji) maker Kaga Kiyomitsu1 point

-

I only have 1, so it's by default my favorite! It was early in my collecting. I wanted a good example of a Type 97 kaigunto and came across one that was beat up, gold gilding missing from most of the metal parts, custom saya faded and peeling at the seem a bit, worn leather cover. Yet the guy was asking more than average price! After chatting with him, I learned that the blade was a mumei, Muromachi era blade, the saya was shark-skin, and it had a Fuji mon. I got hooked and bought it, and still enjoy everything about it. To think some sweaty smith was pounding this out about the same time Columbus was sailing the ocean blue .... just hard to wrap my mind around it! Jace, were you looking for photos or just the story?1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

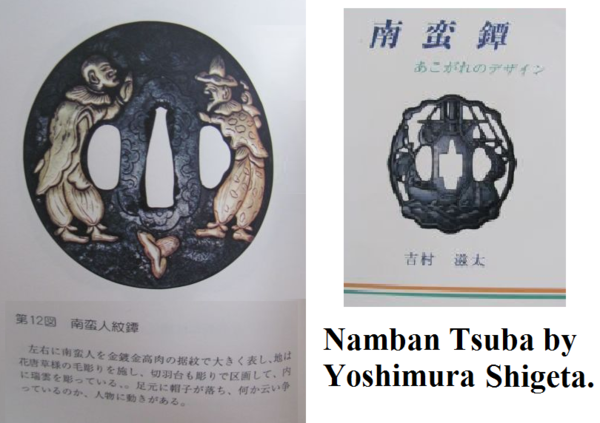

I looked into Namban tsuba a 7 years ago and it's a long time since I read it so no idea if it of interest I expect I had most of the details from the NMB For some reason I can't copy my PDF file it just shows a link. No idea why as I've pasted PDF files before I can open the PDF on my computer as normal I'll have to paste my doc file and it is a bit long and I welcome any corrections. Strange Explanation of terminology. Early Nanban" (1543-1636) Categories like "Kanton", "Kannan" and "Kagonami" belong as subgroups within the "Sakoku Nanban" period, Sakoku "locked country" was the foreign relations policy of Japan under which no foreigner could enter nor could any Japanese leave the country on penalty of death. The policy dated rom 1633 - 1853 Most of these guards reflect Qing taste, and seem not to have arrived in Japan prior to the 1680s. Low quality souvenir grade shiiremono Namban appear to have been produced in China or by the Dutch East India Company in India and imported from the end of the 16th century, (early) Namban examples. Early descriptions of such Momoyama tsuba are very unsatisfactory. Joly (1914) describes them as having ‘a purely Chinese design with symmetrical components’, thus equating them with Kantō tsuba with their origin in Eastern China. There is no justification for drawing a line at 1603 on the importation of these tsuba into Japan. My reasons for this attribution are as follows: • The dote mimi – a form seldom seen on later tsuba of this group. • The very fine, delicate nature of the karakusa-moyo. • The rather bizarre and impractical form of the seppa-dai. • The absence of original hitsu-ana. XXVIII. Namban Styles (Work exhibiting a foreign influence) The style of Namban tsuba, also called Kannon or Kanton tsuba, consists in involved designs of dragons, tendrils, birds, flowers, animals, jewels and characters chased in the thickness of metal, with undercutting more or less developed, and more or less delicate in execution. The influence of China is quite evident. The name Namban means ‘southern barbarians’ and it was used by the Chinese for all foreigners reaching China from the south. It was also used the term used to describe a peculiar kind of hard iron. Gold and silver inlay in nunomé style was freely applied to this kind of sword furniture. It is thought the earliest Namban tsuba date from the early 16th century, and they were copied from European weapons. A learned Japanese writer suggests that the earliest dated from the 17th century, and he recognises as early Namban only those pieces that present a certain mokko shape, peculiar edge, hornless dragons and European characters In the strict sense of the word, Namban should refer only to those fittings which have foreign subjects, other than Korean and Chinese (which were not considered to be foreign). Similar tsuba with Chinese style designs, of symmetrical proportions, are Kanton tsuba. Those with native subjects, of asymmetrical proportions are Kagonami tsuba. In addition to these styles, there were several schools at Nagasaki, such as Jakushi, Mitsuhiro, Kunishige, Umetada of Hizen, and a native inlay school. They flourished through the entire Edo period. NAMBAN, KANNAN (KAGONAMI), OR CANTON TSUBA. These names were used to refer to any extraneous material or style which found its way by trade to Japan from China or by the East-Indian route, and became popular there. About the seventeenth century a craze for foreign designs manifested itself among the artists who made decorative metal work, especially sword guards. The work is characterized in general by very small perforations, a curious undercutting with the chisel, and in most instances a slight use of gold nunome inlay. The introduction of the dragon and a conventional flower into the " tendril design" characterizes the popular canton work made at Nagasaki, Kyoto, and Yedo from the beginning of the eighteenth century. Yamada-Ichirohei is one of the many guard makers of this style who lived in Nagasaki and worked during the second half of the eighteenth century. Tanaka-Sobei II, a guard maker of this style in Yedo, worked during the early nineteenth century. Mitsuhiro I and Mitsuhiro II, two artists of Hizen province, became well known as clever workers in the "canton" style during the early nineteenth century, They are famous for the individuality of their methods. The so-called one thousand horse and monkey designs were their favorite subjects Namban – Hard iron using realistic designs of jewels, dragons, flowers and animals that are deeply undercut Message board I don’t expect many raised hands but if I’d asked about Noda Mitsuhiro’s thousand monkey tsuba I’m sure there would be more raised hands. No so different but I do see some exceptionable workmanship In my earlier post I mentioned the museum book and there was one section that can be improved. This is the Namban section. In my opinion a very under researched area of tsuba. In the album I created I but these in design then date order. I would like to be specific if I go into print. I have cobbled together the information below. I have given no attributions as most of this is regurgitated notes from a hundred years ago It was never a topic for the NMB as there are too many that make unfounded comments but I believe this to be a much more specialist forum with a very knowledgeable membership I’d like your comments and corrections to my notes. I use rounded up dates for ease and I’m not bothered if the dates are a few years out. I may be a bit too early with my start date. As I’m aware there is nothing set in stone especially with Nihonto items so I suggest the most plausible details Namban were produced in China or by the Dutch East India Company in India and imported from the middle to the end of the 16th century. They were copied from European sword guards. Some of the earliest design will incorporate European designs. About the seventeenth century there was a demand for foreign designs. The work is characterized in general by very small perforations, undercutting and in most instances a slight use of gold nunome inlay. The introduction of the dragon and a conventional flower into the " tendril design" characterizes the popular canton work made at Nagasaki, Kyoto, and Yedo from the beginning of the eighteenth century. Namban dates approximated for convenience: Early: 1550 - 1650 Middle: 1651 - 1750 Late: 1751 - 1850 Namban features Design than encroaches over the seppa dai Design resembling fine to delicate filigree work Can be solid Beaded mimi Raised katchushi style mimi Oval is the most common shape No hitsu ana Hitsu ana added post manufacture indicating this to be foriegn manufacture Hitsu ana incorporated during manufacture indicating this to be Japanese manufacture Hard iron Canton: Integrate design in a Chinese style that is symmetrical Kagonami: Integrate design in a Japanese style that is asymmetrical Hands up if you like Namban tsuba This topic was posted on another message board but thought it would also do well here I don’t expect many raised hands but if I’d asked about Noda Mitsuhiro’s thousand monkey tsuba I’m sure there would be more raised hands. Not so different but I do see some exceptionable workmanship with Mitsuhiro’s tsuba In some of my earlier posts I mentioned the museum tsuba book I’m working on. There is one section that can be improved. This is the Namban section. In my opinion a very under researched area of tsuba. In the draft book I put these in design and then date order. I would like to be specific if I go into print. I have cobbled together the information below. I have given no attributions as most information is regurgitated notes from a hundred years ago I’d like your comments corrections to my notes. No rush maybe something to mull over during the Christmas holiday. I use rounded up dates for ease and I’m not bothered if the dates are a few years out. I may be a bit too early with my start date. As I’m aware there is nothing set in stone especially with Nihonto items so I suggest the most plausible details Namban were produced in China or by the Dutch East India Company in India and imported from the middle to the end of the 16th century. They were copied from European sword guards. Some of the earliest design will incorporate European designs. One big step would be to have proof of manufacture outside of Japan and some dated examples About the seventeenth century there was a demand for foreign designs. The work is characterized in general by very small perforations, undercutting and in most instances a slight use of gold nunome inlay. The introduction of the dragon and a conventional flower into the " tendril design" characterizes the popular canton work made at Nagasaki, Kyoto, and Yedo from the beginning of the eighteenth century. Namban dates approximated for convenience: Early: 1550 - 1650 Middle: 1651 - 1750 Late: 1751 - 1850 Namban features Design than encroaches over the seppa dai Non standard seppa dai shape Design resembling fine to delicate filigree work Hard iron Can be solid Beaded mimi Raised katchushi style mimi Oval is the most common shape No hitsu ana Hitsu ana added post manufacture. Would this indicate foreign manufacture or a later addition? Hitsu ana incorporated during manufacture indicating this to be Japanese manufacture Styles Canton: Integrate design in a Chinese style that is symmetrical Kagonami: Integrate design in a Japanese style that is asymmetrical A bit more info: There are 61 tsuba at the museum dated between 1600 to 1890 There are three unusually thick tsuba that are 7mm+ tsuba and date pre 1750 Previous snippets from Namban posts on the NMB Those tsuba that are today called Namban (literally ‘southern barbarian’) appear to have been produced in China or by the Dutch East India Company in India and imported from the end of the 16th century. The category also includes reproductions of these imported pieces later made in Japan’. Ogawa (1987). This remains an interesting thread. I continue to be convinced that MOST of what are counted as "Namban tsuba" are mish-mash creations of stock motifs that reflect the Rampeki or "Hollandamania" of the late 18th century. That fad was a popular phenomenon of mass culture. Namban portrayals of this era show European carrying swept hilt rapier. Bilobed and cup guards that inform many "Namban tsuba" date from the 18th century. There were, of course, Continental military campaigns going on as the Momoyama era was passing, so I think it is not surprising that "Chinese" guards were repurposed by Japanese soldiers. All of those things get conflated as "Namban." From the quote above Ford was referring to the Azuchi-Momoyama Period approximately dated from 1573-1603 not any part of the Edo Period. I personally extend the date of the Azuchi-Momoyama Period to include the Siege of Osaka castle which ends in 1615. After the battle Tokugawa Ieyasu had killed off anyone else that could have had any claim to rulership of Japan (i.e. Toyotomi clan). A great proponent of foreign "Nanban" culture in Japan of this time period was the Shogun Oda Nobunaga. The popularity of foreign culture continued under leadership of Toyotomi Hideyoshi to include the invasion of Korea 1592–1598. The only book (I have a copy) ‘The Namban group of Japanese sword guards: a reappraisal" by Dr John Philip Lissenden’ does’t really say anything If one accepts Ford’s premise that the label ‘Namban’ represents a style rather than a school, then the temptation to attribute this group of tsuba to a finite location is greatly diminished. I have no doubt that, in the early days of this style, the main location for their manufacture was, indeed, the immediate environs of Nagasaki. But by the late 18th and early 19th centuries the popularity of these tsuba was universal, to the extent that 'they suddenly overwhelmed a generation' [Homma and Satō, 1935-36], and it is likely that many of the existing schools throughout Japan had adopted Namban traits. Final observations Whether a school or style doesn’t bother me as they will always be but into a section so dealt no different than other tsuba schools Most collectors will just know what a Namban tsuba looks like although some Hizen and Hirado work can muddy the waters Unless there are specific proven Namban examples then it will remain a grey area Reading through I have rethought my order so it may be Original then later added hitsu ana Raised pattern that encroaches over the seppa dai Pierced work Solid form All I can really ask is for members to agree or disagree with my comments so I can be a bit more specific with my own knowledge. I difficult request If there are any specialist collectors of Namban tsuba would they PM me Grev UK Ford states this is not more than a picture book and it is Japanese here another Japanese book about namban tsuba Nanban Tsuba - - Yearning Design - Yoshimura Shigeta Namban tsuba are indeed an interested subject. There seem to be many differing opinions on what counts as a "Namban" tsuba and where they originate. I have my doubts about any VOC origin. I can fully appreciate the better examples, and think oneday their status in Japan will increase and they will become more sought after. James McElhinney has been writing articles on the subject for the JSS/US; I think you would find them interesting. Grey If I remember well, our member Docliss has written a thesis on Namban tsuba. Cost = $50 + P&P No idea if this is any good http://www.amazon.co...s/dp/1554043654 Grev, Here is my take on the subject: Stylistically, namban tsuba are exactly comparable with Chinese metalwork and in particular items from the regions towards the Himalayas - see Tibetan saddles, pen cases and allied items. A good number of Chinese swords have guards decorated with similar pierced, scrolling tendrils. An important consideration is that most Chinese swords do not have an habaki and are fitted into scabbards that consist of little more that two pieces of wood covered in leather of more or less rectangular section, hence, that part that in Japan would be called a seppa dai, visible when the sword is drawn, decorated and rectangular. There exist a considerable number of Namban tsuba that have had hitsu ana cut through the original design and have these rectangular, decorated 'seppa dai'. I would suggest these are of Chinese origin, the obvious source being trophies taken in the Korean campaigns and adapted to fit the returning samurai's wakizashi. This flaunting of captured trophies created a fashion trend that was satisfied by Japanese tsuba makers, and probably by workers in the Chinese colony at Nagasaki. These later tsuba have a more normally shaped seppa dai, although still often decorated, and hitsu ana that are integral with the design. Gradually the original Chinese design were expanded to include anything novel and foreign, such as the VOC monogram and copies of small-sword hilts. If I am correct this would date the earliest namban tsuba to around 1600, those of the VOC and small-sword designs to around the mid 18th century. Ian Bottomley this book could be a good starting reference. Only in Chinese: Iron and Steel Swords of China by Alex J. Huangfu Two funny Namban tsuba for sale on yahoo.jp (not mine). Images attached on the NMB with papers From Ford I think it comes down to the personal bias of the early 20th century Japanese 'authorities. They didn't like them as they represented foreign influence at a time when their interest in tosogu was to preserve Japanese warrior culture in the face of a huge Western 'invasion'. For these self appointed guardians of Samurai culture the namban group were best ignored and blamed on anonymous Chinese makers in Canton or elsewhere....anywhere, just not in Japan. ;-). We see a similar thing happen in the way Bushido is presented to the West by Nitobe, as something akin to a Christian Knightly tradition. In Europe we've moved beyond those sorts of Nationalistic agendas in terms of history, Japan is still very much caught up in it. The ongoing animosity towards Korea, the origin of almost all their metalworking technology, is evidence enough of that, i think. It might be an idea to get a copy of the Heibonsha Art Survey book , Namban Art of Japan to get some more detailed and reliable background to the genre. I fear the tosogu world's ideas may be hanging in a vacuum unrelated to what was really going on in Japanese cultural life back then. I think that this feature is understandable when we consider how these pieces might have been made. Those Chinese craftsmen I mentioned were apparently kept in guarded compounds and treated very poorly by the Japanese samurai class. Very little contact was allowed between these lowly foreigners and the Japanese population. Contact with the warrior class would have been even more proscribed. If they were making items for local sale then I imagine what was made, or ordered by intermediate merchants more likely, would have been made based on drawings. Without any first-hand understanding of how tsuba were mounted the seppa-dai area was treated to decoration just as the rest of the piece. The real problem with this whole subject of Namban tsuba is that Japanese authorities are notoriously poor when it comes to providing references or citing reliable evidence. Academically speaking the scholarship on tosogu is still very much in it's infancy. In essence we really don't have much more than guesswork thus far. I've found no actual evidence of so called Namban tsuba having been made outside of Japan. My thinking presently, informed by what I've learned about foreign trade and Shogunate controls ( cargo lists actually exist from the late 16th and 17th centuries), is that Namban tsuba were made by those groups around present-day Nagasaki, Hizen, some in Higo, Hirado etc. There were groups of Chinese craftsmen working in tightly regulated compounds in the actual port town of Nagasaki. I would suggest that many of the more crude types may have come from their hands. By the start of the Edo period the penalty for exporting anything even remotely connected to arms was death, often including the culprits family also. What was allowed in was also tightly regulated because of the need to control the outflow of silver and to a lesser extent gold. I think it highly unlikely that warriors would wear anything on their swords that would be understood to have been imported in contravention of government regulations. It would have been a bit like taking coal to Newcastle anyway :-) PM reply Nice post, but incomplete. At times Chinese merchants and shipping outnumbered the Dutch at Nagasaki by more than ten to one. Foreign goods also entered Japan by way of the Ryukyus, Satsuma and Tsushima. Many "Nanban" tsuba imported by the Dutch were made in Indochina, Java and India. I have evidence and original records. Proposing a dating system as a way of organizing Nanban tsuba is a great idea, but it needs one with historic logic, not convenient divisions of time. I agree with you about Lissenden. Lots of facts but no ideas. All kantei, no kansho. Still for the time being it's better than nothing. It is true that Yagami and other Hizen makers produced many Nanban style guards, and yes, Nanban is NOT a school, but an assortment of foreign styles. They were also made in Osaka, Kyoto, Hagi and Edo. What I have discovered is why Nanban tsuba were imported and copied, who was wearing them and why. These facts are nowhere to be found in any of the sword literature. You must get out of the (commercial) sword world to make real progress. I applaud your enterprise. Keep at it! James Hi Grev, The Namban Art of Japan published by Weatherhill-Heibonsha in 1972. is a good place to start. Don't forget to go through the bibliographies of everything you read. Nothing in any of the available sword/kodogu literature provides a sufficient explanation of the history of Nanban tsuba. Absolutely nothing. What is out there is either very superficial or downright incorrect. When I dove into this my old friend Ogawa Morihiro at the Metroplolitan Museum of Art said that it was a good task for a Gaijin, that the Japanese have entirely neglected its study, partly because it's not a Japanese style. It's a foreign trade style. My research has delved into shipping records and other historical sources that were overlooked or ignored by people like Henri Joly. Nanban taxonomy is also pure nonsense. "Kanton" and "Kagonami" appear to be dockside slang for Qing Sino-Tibetan style sword guards that were prodiced in the 18th century. You can date them by shape. Square and trapezoidal guards are earlier, ca. 1660-1700, round ones are later, ca 1750-1800+ As for base material I have seen Vietnamese guards with iron bones. One cannot generalize. Japanese were great at carving and hopeless at casting, but Indians were magicians in the foundry. Their Wootz iron is easily as good a tamahagane. Japan exported millions of surplus swords starting in early Muromachi period, usually after the conclusion of an internecine conflict. This scattered discoid guards as a concept all over South Asia, India and into the Himalayas, places where the discoid form was adopted for some sword forms. When Europeans arrived along the spice routes they found swords with discoid guards everywhere. I am not going to tip my hand because I plan to publish a book later this year. The notion that Nanban guards are patterned after European smallsword guards is pretty sketchy. More likely the opposite was true. You will deepen your knowledge greatly by reading up on Nanban culture. Boston College mounted an exhibition a few years ago with a wonderful catalogue that accompanies it. Find a copy. Go to Oxford, visit the Ashmolean and get into the Jameel Collection. Go to the British Museum, Birmingham. In the states, Boston MFA, the Met in NYC, the Walters in Baltimore, the Dayton Art Museum in Ohio. Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam had a great show on Sawasa wares. See if you can find that catalogue. There is a crazy Namban koshirae on a sword in the museum at Dresden. A lot of these collections are searchable online. Read up on the VOC & the Manila Galleons. Truth be told, Nanban was just a Japanese word for an international decorative arts style. Most sword collectors have no art historical training and think about these objects as if they were on Antiques Roadshow. Go to Lisbon and the Netherlands. Be a detective. I have reconstructed most of the story, but there is more to be discovered. Check this out: Interesting site. Like it an join the frolic. https://www.facebook.com/Nanban-Tsuba-564035753684007/ I am not one for chat threads or blogs. Grey Doffin sent me your post. He found it interesting. I hope this exchange has provided you with some encouragement and motivation. Good luck!! Cheers, James McElhinney – USA Cont. It's no secret that early Nanban tsuba were imported from Indian, South Asia and China. One on the FB page by Yamada Gensho is a decent copy of a Qing guard according to a Chinese arms expert I know. There is also a tsuba in the Boston MFA that was made in China in a Japanese style. Sword types need to throw away their blinkers. Since many of them were made as Omiyage, you have to be carful about certain patterns which were mass produced in vast numbers, ones like this which are probably late 19th century Yokohama paperweights, perfect junk http://www.ebay.com/itm/NANBAN-TSUBA-Vintage-Japanese-Iron-Samurai-Sword-Guard-1561-/321938190801?hash=item4af502f1d1:g:z4UAAOSwj0NUhaJE The captions on the FB are detailed. Read them and you will get a sense of how to differentiate between imported guards and Japanese copies and Nanban-inspired work. There are four or five signed Nanban posted. The only thing to do is to develop your eye and that means looking at hundreds if not thousands of these things. There are terrific collections in the UK. Forget about talking to dealers and start talking to curators I also like so much Namban tsuba. But, I have some opinions about some points: - I really don't think that Namban tsuba comes from European sword guards. It is true that there are quite similar in some cases...but as well chinese or Indian sword guards. Many people wants to link namban with Europe, but in that case I think that the Namban tsuba only has link with the "old" namban people, I mean, estrangers coming from the south before 1549. - Also It is very common that people has confusion about "Namban tsuba" and "nippon tsuba with Namban decoration". For example, a tsuba fro Hirato/do Kunishige with European letters and motifs it is an original Japanese tsuba. But a tsuba marked in China, India, or a Japanese copy of this tsuba are Namban tsuba. The work of Torigoye, Haynes and Yumoto is excellent, but their research about Namban tsuba - kanton - kagonami are not such excellent as Lissenden thesis.1 point

-

1 point

-

Thank you kindly, Jean. The museum sounds like a definite place to visit. Glad you were able to adjust some of their fantasies!!! If a 100 Monmé is a rare beast, then anything larger than that is quite special. There was a time in Edo when people vied for larger hand-held cannons. You sometimes come across references to 一貫目 Ik-kan-mé, which is 1,000 Monmé which must surely have been the upper limit, the ball being almost 9 cm in diameter. My chart here goes up to 5 Kan, but that would be for a ‘hand’ cannon resting on a wheeled carriage. I cannot imagine anyone firing without a support/rest; a 100 Monmé blank is usually fired squatting or kneeling and even then it’s an art, a test of mettle. I don’t recall ever seeing one being fired from a standing position. On Sunday June 12 I accepted the challenge (do not ask), rammed it tight, and (left hand bound to the barrel) fired the 50-Monmé standing up, but it nearly knocked me off my feet, even a blank. 926 grains blackpowder.1 point

-

Your eyes, with it in hand, are the best judge. I would look at the corrosion to see if any of it looks to have worked it's way into the engraving. Engraving after the corrosion should be clean cut.1 point

-

That book has perhaps the largest collection of Tameshi mei.1 point

-

I think you should get a copy of Markus Seskos book on tameshigiri then.1 point

-

0 points

-

0 points

-

Doesn't sound like much of a friend to me. A friend would have disposed of it discreetly and never mentioned the matter again.0 points