Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 02/14/2022 in all areas

-

All, In my opinion Piers has a valid point. Swords permanently displayed in glass cases not only look as if they are museum exhibits, but after a while become simply part of the furniture of the room. All of my swords have bags I make from old kimono, or fabric scraps, in which they live. They are thus protected from light and knocks whilst standing, leaning together, in the corner of my study. There the temperature is relatively constant and the humidity relatively low. As a result there is no reason to oil the blades provided, I wipe them clean before returning them to their saya. The process of un-bagging them, to look at them, is like discovering them afresh. Ian Bottomley6 points

-

3 points

-

Well, I've heard it said that to a dealer if buying it is a wakizashi, if selling a katana!!! The point about it is, I believe, that in their day of the 16th century they were considered katana and should still be so today, IMHO. BaZZa.3 points

-

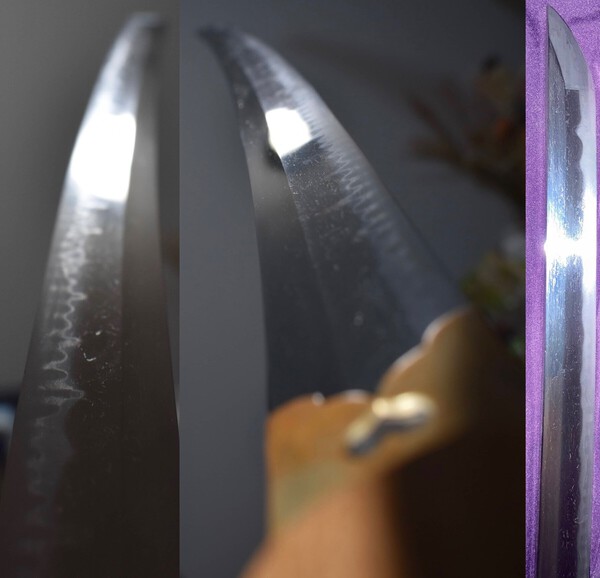

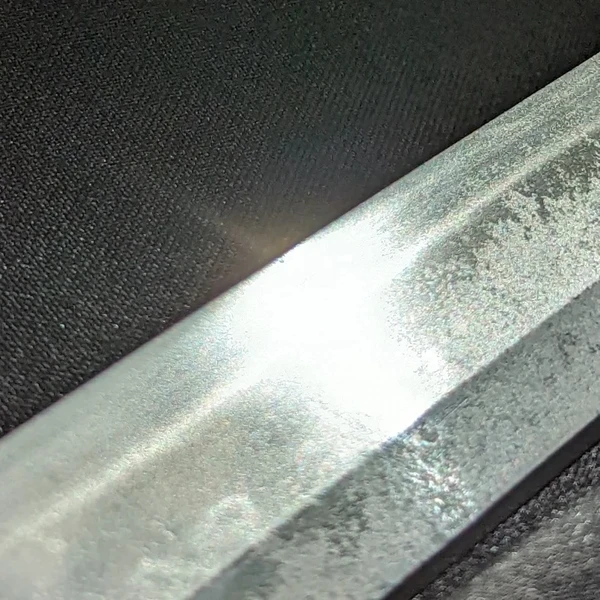

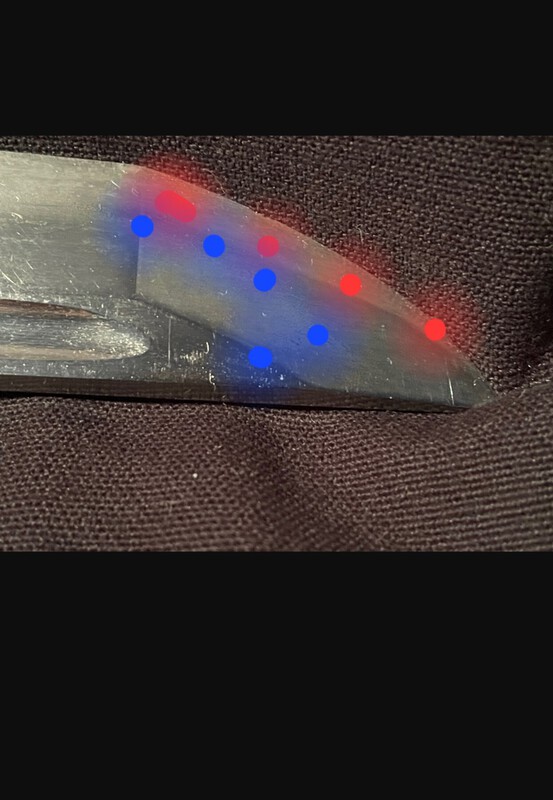

Hello again everyone, I know this blade is no treasure - it being a cheap sengoku study piece I grabbed a couple years ago - but the habaki made it pretty fitting for this occasion, so I hope you will forgive it. Also, I'd like to see if my Kantei skills are getting better so here goes: sugata is stereotypic late Muromachi, short (barely at 2 shaku) not very tapered and saki-sori so its a katateuchi; itame with some masame (mostly in shinogi) and heavy amounts of ji-nie, and what looks like a nie togari-gunome hamon. That makes me think I'm looking at a sue-seki or some other sengoku mino blade, Kazu-Uchi mono probably. Would this be a correct assumption? Also it seems to be signed by some "kanesada" but the signature doesn't match any examples so I got it under the presumption it was gimei. Would that be correct? Thanks again everyone2 points

-

2 points

-

Juan, you are correct. One SHAKU is 30,3 cm, and when a sword is sold or handled in our days, it is a good idea to respect the actual denominations, independent of what the purpose or use it had in the olden days. So a TANTO is up to one SHAKU long, a WAKIZASHI has a length between one and two SHAKU, and TACHI and KATANA have more than two SHAKU. Selling or buying a blade with a few millimeters off the mark may sometimes mean a remarkable price difference! The "funny heart" HABAKI you mention in the title of your post is a standard symbol of the brave and fearless SAMURAI. It is called INOME, the 'never-twitching eye of the wild boar' (https://www.mandarinmansion.com/glossary/inome)2 points

-

There are a number of closely related non-destructive methods of elemental analysis of metals and alloys, but the basic method is XRF or EDX. So, if you have a large enough sample size you could describe the elemental components of different tsuba. Some years ago I did this for Marcus Chambers and someone did this for Ford at V and A. Normally this is quite expensive although the analysis takes little time and the calculations are done with internal software. But you might find someone who has access to an instrument that shares your interest. The steel industry does this routinely. The data could be separated into like groups statistically. Perhaps a good chemistry/metallurgy BS thesis subject.2 points

-

2 points

-

Hi Bruno, Just seen your tsuba. the design looks familiar. I posted this tsuba some time back. It was part of an old collection I bought at auction. It was not in great condition and had a lobster kashira rivited to the seppa dai. Probably used as a paper weight. My tsuba is iron and I put it down to possibly of the Ono school using a Yagyu design. Pics of mine with kashira attached. Best regards, John2 points

-

1 point

-

I hope you found interesting this curious story regarding Spanish collections of Japanese arms and armours . A Japanese armor with a Mexica weapon and a Turkish shield. The armor was a gift from the Tenshō Embassy to King Felipe II of Spain, originally, it seems that it was mounted properly, along with other armor, a nagamaki and two katana, very possibly tachi ōsuriage. However, they were later put away, and in the 19th century they were reassembled in this way. The reason? At that time, strange oriental things were considered "Indian things" as well as American ones. It is very possible that the assembly was after the government of José Bonaparte in Spain, when the pieces had been moved to France or another place in Madrid and that on his return they were assembled in this way, due to ignorance of one culture or another, or rather, out of laziness, because they are not considered pieces of great value. There is a contemporary example. After the French invasion to Spain, numerous works from the Prado National Museum were taken to France, including the collection of grated rock crystals, gold work, cameos and pietre dure called the Dauphin's Treasure, donated by the Soleil King Louis XIV to the first French King of Spain, his grandson Felipe V. In that collection there was a Japanese tea set, lacquered in red urushi. How this set arrived to this collection? A group of samurai of Ishida Mitsunari's side brought to Siam after loosing at the battle of Sekigahara. An embassy of the Sun King bought these pieces and added them to the Treasure of the Grand Dauphin of France. Upon the return of this collection to Madrid after the War of Independence, the curators of the Prado Museum rejected these pieces considering them "Indian things" so they went to the Museum of America until 2016, when a researcher discovered all this history. Today they are once again incorporated into the Dolphin Treasure of the Prado National Museum. Regarding again about the yoroi, it was burnt in fire at the end of XIX century, and today only remains some of the iron parts.1 point

-

Thomas, I will try PM's. No Mino book is not archived on NMB. It is 1993 pre-digital.1 point

-

When shipping blades I usually put a layer of oil on the bare blade, wrap it in saran wrap and put it on a board bigger in all directions than the sword with a small peg through the mekugiana into the board and then zip tied to the board. Wrapped in paper then bubble wrap and into one of the FedEX triangular shaped shipping boxes. Koshira wrapped in bubble wrap and placed in same tube. Never had a problem - knock on wood !!!! BUT in this pandemic with the amount of shipping going on they are being more than rough trying to get everything to where they want it to be.1 point

-

Now that I look more closely, I believe this is Seki ju Kanemoto. 関住兼元1 point

-

Juan, I forgot to mention that the Japanese use the INOME symbol upside-down to what we do when we use it as 'heart' symbol..1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

If a random smith uses the name of another smith on a sword that was not produced by the smith named, I think that would qualify as gimei (not saying concretely that is the case for this particular blade, just generally speaking) would it not? It does beg the question why it was signed with Mino as opposed to Noshu (i.e. if Gimei, was the individual who put the signature confused between the 2 or was there high tolerance on liberties taken with choosing between the 2), they are one in the same according to references Mino (美濃 = Nōshū 濃州) and from what I can tell in my books is that Kanesada (depends on which as there are many) had the honorary of Noshu-ju (at least in part) among a few generations. To list a few from Seskos books: Kanesada 2nd Generation, Eisho 1504-1521 - Noshu seki-ju Kanesada saku (signature does not compare well to his given example in the book) Kanesada 3rd Generation, Tenbun 1532-1555 - Noshu seki-ju Kanesada saku (signature does not compare well to his given example in the book) Kanesada (student of 2nd, assistant of 3rd Gen), Koji 1555-1558 Noshu seki-ju Kanesada Kanesada (son of 3rd Generation), Tensho 1573-1592, Noshu-ju Kanesada Thanks for sharing pictures and observations about your sword, Juan! The Habaki is certainly a good fit for today.1 point

-

Mmmm... So one minute you are saying that no smith is awarded a title relevant to his place of work because of some "common sense" idea that existed in Japan at the time. Then when you are shown examples of how your statement is incorrect, that is simply coincidence? Interesting...1 point

-

https://markussesko.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/nihontocompendium-e1.pdf Have a look through this document where there is a section listing the titles awarded to smiths, their work periods and their place of work. Some smiths are awarded titles linked to their place of work. With Nihonto, once you start stating any rule or idea as being an absolute, then you will quickly find someone who can show you something different.1 point

-

Also I need to point out that it is normal for completely unrelated smiths to use the same name by coincidence. I can give many examples:Osafune Kiyomitsu(長船清光),Kashuu Kiyomitsu(加州清光)and Harimadaijou Fujiwara Kiyomitsu(播磨大掾藤原清光), they have the same name Kiyomitsu but are smiths from different schools.1 point

-

Hi Yanchen, There's an article here on how swordsmiths received their titles. https://markussesko.com/2013/02/19/how-honorary-titles-were-conferred/ Yes it is unlikely that a smith would make up a title, but less so that someone faking a signature was ignorant of the listing of smiths and their titles or relying on the buyer's ignorance of that listing and thinking that "Mino no kami" and a name associated with Mino swordsmiths added value to a Mino blade in the eyes of someone who didn't know better. The true answer of course is that we'll never know, but whatever the reason was, my view is that the false title would lead to a failure at shinsa.1 point

-

1 point

-

Hi Yanchen, I think that there are two choices here, either the smith awarded a false title to themselves and signed that way or that someone else got creative and added a completely false signature to a blade. I think that either way the blade would fail shinsa unless the signature were removed. I think it's difficult to draw a conclusion as to age of the blade based on sugata alone as the suriage and perhaps some re-shaping work at the kissaki (not much turn back on the boshi) do give it the appearance of a kanbun style sugata. The hamon is fairly typical for late muromachi mino work and so is the hada where the shintetsu isn't showing (mokume with some nagare), so I don't think that that is a bad call. For me, I don't think that it was made to be used as a katate uchi because the original nakago jiri isn't there - the squared off nakago jiri suggests that it is suriage, maybe o suriage, so I feel it was a katana that someone cut down to this size. With katate uchi there is often a second mekugi ana because the tang has been extended by means of machi okuri so that it could take a longer handle for two handed use after the fashion for one handed fighting changed. The filled mekugi ana was perhaps put in when the (for me, false) signature was done to give the appearance of age as it would be the upper mekugi ana that was used in a re-purposed katate uchi.1 point

-

In my view this is an Early Edo period wakizashi(Shinto) made by Mino no Kami Kanesada(美濃守兼定) I think this smith, Mino no Kami Kanesada(美濃守兼定), is just a random smith who use same name with famous Kanesada by coincidence, because no one in the famous Kanesada family has the title Mino no Kami(美濃守). So it cannot be a gimei.1 point

-

How could you know this is a Sengoku period blade? It looks like an Early Edo period blade for me.1 point

-

Found it, by Jussi I think modern classification is sometimes too strict when it comes to "borderline" things, as I don't believe it would have been a big deal back in the day if your sword is 59 cm or 61 cm. I picked 10 swords from Kantei-Zenshu that were listed being used in katate-uchi style by NBTHK. Here are the blade lengths, and 3 of them are wakizashi but the few cms wouldn't have mattered back then. 66,8, 66,3, 64,8, 64,3, 62,3, 61,8, 60,6, 58,3, 56,5, 53,3. Here are portions of the description of swords that are 56,5 cm and 53,3 cm.1 point

-

1 point

-

You assume correct for Seki, file marks correct too What length is the blade?1 point

-

Hello all! First, thank you Rokujuro for your excellent post and a breakdown of the misleading statements found in the wikipedia sites!! Much appreciated. I was wondering, Rokujuro, is there any way that you could add that information to the wikipedia sites so that others are not “misled”? Now, what is of interest, I have found 4 former threads on the NMB site that deals with some kind of cast iron questions. And I believe there are more threads on the subject on NMB-(the 4 threads are listed below)- NMB thread of 2010--- https://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/5697-what-do-you-make-of-this/ NMB thread of 2012- https://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/9339-beware-of-torigoes-temper/ and the other is – from a NMB 2014 thread- https://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/15302-casting-vs-carving/ And the last is the NMB thread– from 2016- (I find the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th posts on this thread very interesting) https://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/18598-cast-sword-fittings-by-markus-sesko/ Three of these threads were started 5 years (first thread listed), 3 years (second thread listed), and 1 year (third thread listed) before the discovery of the Nara site tsuba mold finds (in 2015). And in previous posts to this (current thread) there was mention of metallurgical examination of iron tsuba. However, as stated in one of my posts, that examination was only conducted on 2 tsuba (and they were discerned not to be made from cast iron). Now, if this subject of Edo period cast iron tsuba is to be resolved, may I suggest the following (and I would like to inform the reader that I have no vested interest in the outcome one way or the other – I just find it a fascinating subject for exploration)- I suggest gathering at least 20 tsuba from different "reputable" dealers (I consider that number of tusba a relatively fair sampling - although others may think that fewer or more would be better). In the dealers listings of these tsuba they would be listed as Edo period and would appear that they could be made from cast iron (perhaps including a few Nanban types). Then have a metallurgist cut (or maybe it can be done by chemical or other less invasive means?) and analyze each tsuba. If a "cast iron" tsuba is found, then the examination can stop at that point. The conclusion that can be drawn is that if there is one cast iron tsuba, there are probably many others "out there". If no cast iron tsuba are found in the sampling of those 20 tsuba (or more or less), then there is an extremely high probability that Edo period and earlier tsuba were not made from cast iron. Unfortunately, there is really no solid definitive historical written proof (that I can find) that states that cast iron tsuba were “not” being made in the Edo period (I refer the reader to my earlier post that includes reference to the Transactions and Proceedings of the Japan Society, London 1893-5, and to the reference of the Professor A.H. Church collection). I believe that the above-mentioned scientific way of discerning the metal used in Edo (and possibly earlier) tsuba would be the only way to finally “bring to a close” the “cast iron” tsuba debate. The expense for this test, and the results, could be offset by the individual if the research obtained was used for that person's masters or doctoral thesis project (as was Dr. Lissenden's paper on “The Namban Group of Japanese Sword Guards: A Reappraisal” used for his thesis project for his Master of Arts degree in East Asian Studies, in 2002). I do apologize to the readers of my posts on this thread for being a relatively new beginner to this vast and complicated subject of tsuba. I am certain that the below Zen quote is applicable to my naïve state of mind on this subject- “If your mind is empty, it is always ready for anything, it is open to everything. In the beginner's mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert's mind there are few.” ― Shunryu Suzuki With respect, Dan1 point

-

Gentlemen, without wanting to discuss the subject of early (= EDO JIDAI) cast iron TSUBA, I would like to mention that there are some incorrect contents in the text cited by Dan: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferrous_metallurgy ....“Around 500 BC, metalworkers in the southern state of Wu achieved a temperature of 1130 °C. At this temperature, iron combines with 4.3% carbon and melts. The liquid iron can be cast into molds, a method far less laborious than individually forging each piece of iron from a bloom..... Cast iron is rather brittle and unsuitable for striking implements. It can, however, be decarburized to steel or wrought iron by heating it in air for several days....." My comment: The cited temperature of 1.130°C is too low to produce iron in a small-scale bloomery furnace. The metallurgical literature dealing with this subject says 1.250°C are necessary, and that is also my personal experience when making iron in a Celtic bloomery furnace. Furthermore, it is not correct that iron combines with carbon at 1.130°C to form cast iron, it is just the other way round: In the direct-reduction process, there are often 'hot spots' in the furnace (TATARA as well as European) near the blower vents where the temperatures can rise up to the melting point of iron. So, only when melted (= liquified) iron was already present as result of the reduction processs, it would have been able to take on a lot of carbon (indeed up to 5% in modern production) when it came into contact with the charcoal. Carbon migration in steel depends on the temperature. This alloy now (= cast iron) has a low melting point which can be as low as 1.200°C or even less, depending on its composition. Decarburizing this cast iron now - that description is correct - requires indeed several days of heating up the cast iron items. The important additional information in this respect is that it needs about 1.000°C for up to five days, depending on the dimensions (= wall thickness) of the items. But even after oxidizing excess carbon to carbon dioxide in the cast iron, malleable cast iron does not have the same ductile properties as wrought iron. I have referenced Chinese metallurgy methods because I find it very believable that Japan could have learned some of their metal working techniques from China. That is of course true and there is a lot of evidence for it. I also found another wiki site that deals with the Japanese tatara. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_Japanese_iron-working_techniques “The traditional Japanese furnace, known as a tatara, was a hybrid type of furnace. It incorporated bellows, like the European blast furnace, but was constructed of clay; these furnaces would be destroyed after the first use.[1] According to existing archeological records, the first TATARA were built during the middle part of the sixth century A.D.[2] Due to the large scale of the tatara, as compared to its European, Indian and Chinese counterparts, the temperature at a given point would vary based on the height in the furnace. Therefore, different types of iron could be found at different heights inside the furnace, ranging from wrought iron at the top of the tatara (furthest from the heat, lowest temperature), to cast iron towards the middle, and finally steel towards the bottom (with varying degrees of carbon content.)[3] Importantly, TATARA did not exceed 1500 C, so they did not completely melt the iron.” The sizes of TATARA and European furnaces can only be compared when you look at similar stages of technical development. The Celts were the first in Europe to produce iron about 800 B.C. Their methods did not change much and lasted until the end of the Middle Ages (about 1500 C.E.). Only then blast furnaces came up, at first in small dimensions. We know that large Iron Age bloomery furnaces (made from clay) were run by a team, producing more than 100 kg of iron in one go in furnaces up to three meters of height. We also know that in the Japanese KOTO era most smiths produced their own iron and steel for their sword production. We have to consider that a TATARA which could be run by three or four members of a forge might yield a raw output of up to 70 - 80 kg of iron and steel in two to three days. More than 200 kg of SATETSU (black iron sand) and ca. 250 kg of charcoal would have been necessary for that. This output of metal is not - as wrongly described - found in different heights inside the furnaces. The region of the highest temperature in a bloomery furnace is near the vents or a little above. That is the reduction zone where the chemical process takes place - it is not a melting process! We find most of the low carbon steel (= iron) in the middle of the reduction zone. Cast iron requires higher temperature and will be found near the vents, while steel (= 'high carbon iron') is often mixed with the iron or close to it. In the end, when you break open the furnace/TATARA, you will find that there is no real order of steel alloys, and you will have to cut the whole KERA (= bloom) to small pieces and examine every single piece. Concerning the last phrase of the text above, the melting of iron starts at a temp. of 1.538°C. There is no way of 'not completely melted iron' in a bloomery furnace as this would have produced cast iron which, as we know, is not usable in a forge. These text contents have obviously been 'simplified' by non-expert authors who did not understand the processes involved. This is misleading.1 point

-

Thanks Dave…. Yes Stephen posted some great resources. At first it can seem a bit overwhelming but the discovery of this history is addictive. I’m really enjoying the path. Thanks1 point

-

二代理事長 (nidai rijicho) – The second-generation chief director 塚本正和 – Tsukamoto Masakazu 現存する (Genzon suru) - existing 利器組合事務所 (Riki kumiai jimusho) – Sharp-edged tool guild office1 point

-

Another interesting article Kotetsu Katana of Kondo Isami https://Japan-forward.com/historical-Japanese-sword-kotetsu-katana-of-kondo-isami-discovered/1 point

-

Having found a very interesting katana at an antique show this past weekend led me to this article below on the smith by Markus. It's pretty wonderful to be able to learn so much about a swordsmith's life and career, and greatly enrichens the experience of studying his work. https://markussesko.com/2013/05/13/from-the-life-of-fujieda-taro-teruyoshi/1 point

-

1 point

-

That nakago looks suspicious almost looks tempered like the sword is suriage.1 point

-

I think one has to make a choice between what is on permanent display and what is not, and when to switch on the display lights and for how long. In Japan I often see collectors and dealers eyeing their visitor, listening to them, and then deciding if and what to bring out and show. For security reasons alone (different meanings to security here) it makes sense to remain in control and not to have everything up front and on display.1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

I can understand how the kanji looks like Mune(宗) or Kage(景). However, I think that the kanji is neither Mune(宗) nor Kage(景). If I have no background knowledge, I naturally read it 秀早(Hidesaki/Hidehaya). But the problem is that there is no such a mei in my references.1 point

-

This can be said for all of us! There's a wonderful Chinese story about the 人間万事塞翁が馬 'Ningen Banji Sai Ou Ga Uma' as it's called in Japanese. Every time the villagers make a judgement on the farmer's next turn of luck they turn out to be wrong, and nothing is as it seems. The farmer's attitude expresses the Dao. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_old_man_lost_his_horse1 point

-

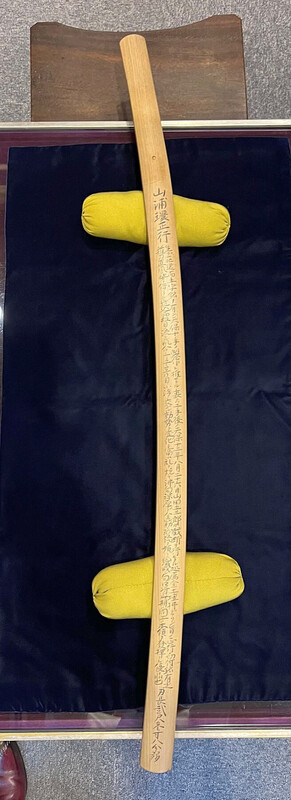

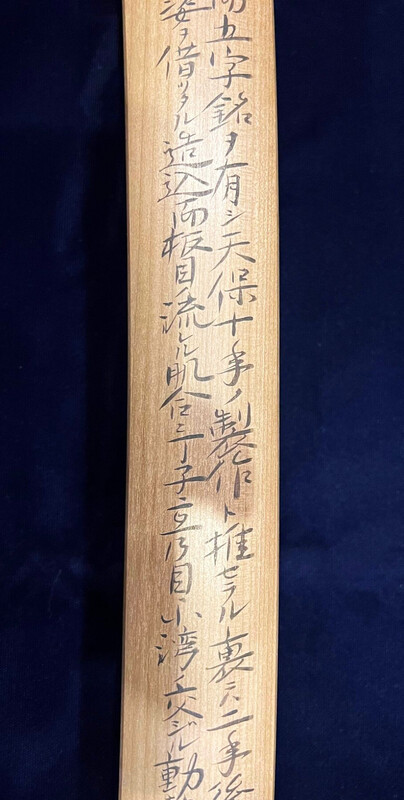

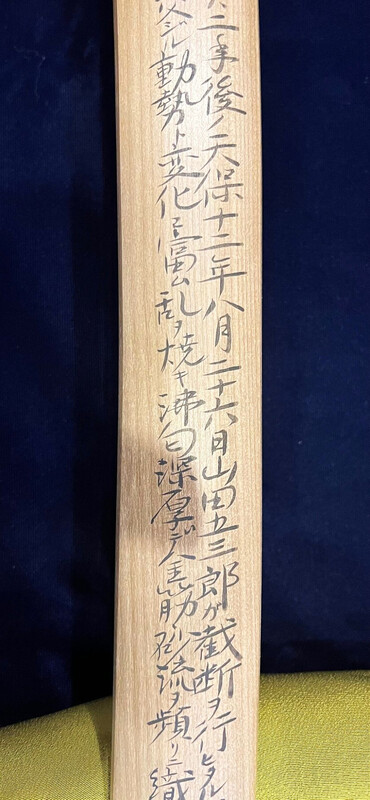

That, to my surprise went very fast this time. The Sayagaki by Tanobe is already done - and I even have a nearly full (since opposite side missing) translation by @Markus for it. The Japanese reads as: Or I did get a German translation to this as well, but maybe @Markus can help for others in here with an English translation since I doubt I am able to translate a Japanese to German translation to English without making any errors.1 point

-

Please forgive for not updating a longer time. It missed being submitted to Juyo, so the first try then will be this year - another year in Japan! The time will be used nevertheless with sayagaki. I though got some additional pictures that show more of its beauty and make me look highly forward to it. Find them attached.1 point

-

I think it is a nice sword regardless of whom made it. I can understand the Hoshō attribution very well and due to the strong masame I would personally have gone that was too. As I do not know the fine details amongst various Yamato smiths, going default to Hoshō with strong masame would be my guess. However I think one obstacle in identification is the extremely small number of signed tachi from Hoshō school. I think I have 3 so far, Jūyō Bijutsuhin by Sadayoshi, Tokubetsu Jūyō by Sadaoki and Jūyō Bunkazai by Sadatsugu. I feel regardless of the attributions (good or bad) it is sometimes very fun trying to figure out what would be the factors that made shinsa team (or someone else) choose that specific attribution.1 point

-

Well that's certainly a very interesting example. Nice bit of digging there Dan Here's a clearly cast iron tsuba, NBTHK attributed to Yagyu, complete with the telltale raised circular "scars" on the seppa-dai, where I suspect the iron was poured into the mould. There's also a lot of "webbing" remnants in the kogai-hitsu-ana and elsewhere. Maybe it was made from a sand casting with two halves? I accidentally came across this example when I was looking for examples of this particular motif, but then noticed it was cast. The translation comes from MauroP in an NMB post where Dale assigned everyone some "Homework".1 point

-

Stephen, there would have been a few members out there who had never even been born when that song came out. [1979] You are right though it is darn hard to get it out of your head once it is in there! [and it's not a favourite either!]1 point

-

You are a wag Stephen- you spice up a few posts for the members. You make me smile anyway. Roger j1 point

-

This officer definitely had a individualist streak! But we've seen that with other gunto, too. Just the first one we've seen in RS fittings. Gareth, while anything is possible with gunto, I can assure you the haikan on this was meant for a leather cover. Rinji seishiki haikan look like this: Here is a photo of several styles of haikan made for leather-covered saya:1 point